Fear and Closing in Big Bend

Where Have All the Boatmen Gone?

Back in 1995, when I needed to get out of Houston for awhile, I moved to Terlingua, Texas, in the Big Bend, for six months. Like everyone else, I read Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire while I was there, and what most impressed me about that book was Abbey’s comfort in the notion–realized during some personal behavior that might today be classified as bad naturalism–that the desert would prove impervious, in the long run, to the inevitable piddlings of the few men and women who might choose to spend time brief or sustained toughing it out upon the planet’s most exposed habitat.

And still, going back years later, I was afraid of change.

I’d heard there was no more sundown beer-drinking allowed on the porch of the Terlingua Trading Company, in what used to be more reasonably known as the ghost town, in deference to an increasing number of tourists and residents both.

I’d heard the river outfitters who gave Terlingua its first real reason to be since the devaluation of quicksilver were drowning in dust, scrambling to survive because of drought, or because drought-ridden Mexico wasn’t releasing the water a treaty demanded, or because a would-be jet-set millionaire was draining the aquifer to feed a ridiculous golf course at Lajitas, while the Rio Grande itself petered out in marsh before reaching the Gulf.

I heard that the border was closed.

I’ve crossed that border a few times. I’ve taken a row boat to Boquillas, at the southern end of the National Park, and purchased scorpions fashioned of copper wiring. I’ve walked both sides during three days canoeing Boquillas Canyon from Rio Grande Village to La Linda Bridge. After an afternoon of horsebacking up into the pink striations near Lajitas, I paid a few bucks to be rowed the few yards across the river for lunch. My dog swam after me. He tried to jump in the boat for the return trip, but I tossed him out, and he swam back too. Don’t tell Border Patrol.

That dog symbolized fear. When I decided to move to Terlingua, I was assaulted by the projected fears of everyone I told, never mind those of my own. I was advised, fundamentally, that I needed a gun, to stave off hypothetical bands of modern-day Pancho Villas storming across the border to colonize my rented shelter and, who knows, shoot my dog I guess.

I’m afraid of guns, so I acquired a puppy instead, named him Pancho, and immediately started worrying that he’d get snakebit.

As it turned out, I was never accosted by anything more threatening than a man inquiring after the whereabouts of my landlord, my dog escaped snakebite, and neither of us got shot.

But much indeed has changed since my last visit. Angie sold the Starlight Theater to someone new, and now one can eat a $30 steak in a room that has an indoor swimming pool where the stage used to be.

Far Flung Adventures, Terlingua’s commercial pioneer, has sold out to Texas River and Jeep Expeditions, with new headquarters down the road toward Study Butte. The old Far Flung boathouse has become a bar, The Boathouse, while Texas River and Jeep Expeditions has leased a failed bar and turned it into a boathouse.

And the border is indeed closed.

At least the no-drinking-on-the-porch scare turned out to be a false alarm.

It is reasonable to say that fear is different after September 11, 2001. Patently absurd fears are, if not necessarily more real, then substantially more conceivable. . So there is more money for homeland security, and this means more money for the Border Patrol charged with enforcing the laws of border-crossing.

Officially, historically, with a few exceptions, the border crossings at Boquillas and Santa Elena and San Vicente inside Big Bend National Park, and more prominently at Lajitas upstream, have been illegal and subject to enforcement. Practically, these small crossings have been winkingly overlooked for hundreds of years. Children cross from Mexico to attend school in Terlingua, because school teachers, after all, serve no law enforcement function. Workers from Mexico cross to lay irrigation pipe beneath the lawns of Austin millionaire and Lajitas owner Steve Smith’s expanding golf course, and to go back home at night. The sheer extremity of selection at the Lajitas Store makes it clear that the shop supplies households on both sides of the river. And tourists cross everywhere, usually just for the day, reenacting some simulacrum of lyrical romance overheard in a Robert Earl Keen song.

This is known, in the local parlance, as “traditional use.”

Drug traffickers also drive across shoals in the river in 4×4 Fords, with beds full of pot.

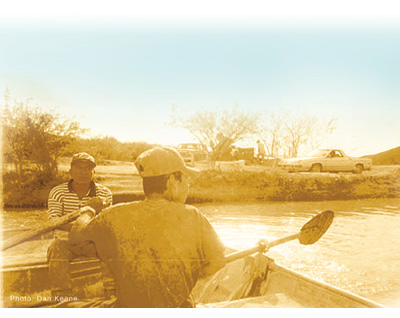

On May 10, 2002, the Border Patrol, which has always pursued narcotics traffickers and illegal immigrants, began, without warning, to enforce the law against crossing, period. Twenty-one people were arrested, including “Gordo,” the 18-year-old boatman who rowed the jonboat back and forth at Paso Lajitas.

Gordo was taken to El Paso, to await deportation. He couldn’t have been 20 yards from the Mexican shore when his boat was confiscated in the middle of the Rio Grande.

“You know what I wish? I wish they’d told us: In three weeks this is going to change.” Greg Henington, proprietor of Texas River and Jeep Expeditions and chairman of the Visit Big Bend Tourism Council, is taking a breather from his move into his company’s new home.

“They’re not stopping anyone who shouldn’t be here.”

On the other hand, Border Patrol is just doing its post-9/11 job, and nobody’s in much of a position to blame them for that.

I check into Lajitas’ faux-Western Badlands Hotel–a discounted $100 a night during the hot months, new slogan: The Ultimate Hideout–and sleep in one of the “Officer’s Quarters” outbuildings. The rooms in the main building aren’t ready yet; the floors have been refinished, the wood is still tacky.

There’s a flashlight mounted to the wall, for power outages, which happen, a consequence of The Ultimate Hideout’s increasing demands upon Brewster County’s rickety electrical grid.

The check-in girl shows me, on a resort map, the parking lot at the little bend in the river where Gordo’s flat-bottomed boat had been confiscated. The resort has erected a plaque at the site:

“Tracks across the centuries indicate that pre-Columbian native Americans used the Lajitas crossing thousands of years beyond the present horizon. Spanish conquistadors were the first Europeans to cross here in the 16th Century… Comanches and Mescalero Apaches arrived after the Spanish. In the 18th and 19th centuries, red raiders from the north crossed the river here in the fall and used the San Carlos trail to strike deep into Mexico… In the 20th century bandits, bootleggers, [and] businessmen used the crossing… Today the historic crossing connects two nations and cultures and is used by tourists and travelers from around the world.”

A few yards behind the sign, Border Patrol has strung up a low length of steel cable between two low steel posts, to block truck traffic. I visit twice, see no agents. The second visit, the Rio Grande’s banks are muddy from an unexpected surge of high water from rains dumped in to the north. There’s a pile of muddy clothes wadded up beneath a yucca in the shadow of the plaque, and just downstream, deep tire ruts in the fresh mud of the American side, disappearing into the water.

Mixed messages everywhere.

“There’s been a rapid growth spurt down there,” is the explanation from Simon Garza, chief of Border Patrol’s Marfa Sector, whose 215 officers cover some 135,000 square miles of territory.

“Apparently it attracted illegal immigrants to come in and seek employment,” Garza tells me. “And where a few years ago maybe the scenario down there was a few tourists going back and forth–and I had other things I had to prioritize as far as responding with the limited resources I have–it rose to a level where it had to be responded to.”

The idea, one surmises, is that a border this long, this porous, this sparsely populated, enforced in this winking and nodding fashion, holds potential threat to what people hopefully think of as homeland security. Since September 11, 2001, Border Patrol has seen its resources and its directive bolstered to the cause, and the unannounced May 10 crackdown served as notice of new priorities.

And freaked everybody out a little. River guides and outfitters weren’t sure how it might affect them: their day hikes into the Mexican side canyons; the negotiation of Rock Slide rapid in Santa Elena Canyon, which requires scouting from the Mexican shore; the customer perception the wrong kind of media coverage might engender, that this largely desolate border could be teeming with terrorists, hordes of Osama bin Ladens using (as the commercials keep trying to tell me) my marijuana money to pay Gordo the $2 to row them across to their staging area, in the Officer’s Quarters, at the Badlands Hotel, in Lajitas, Texas, The Ultimate Hideout after all.

It’s easy enough to mock the idea, and no one who lives on this border seems to put any real stock in it, partly because of the region’s forbidding logistics, and partly because, if we’re all recalling correctly, none of our recent homeland terrorism scares have hinged even slightly on the issue of anyone sneaking into the country. It just makes much more sense to attack from Canada, or Chicago.

The locals don’t blame terrorism for the border closings. They blame Those Bureaucrats In Washington and The Media. The bureaucrats don’t know the border, they certainly don’t know this border, and lacking understanding, they trade in blanket regulations. The government’s failing, they say, is simple lack of flexibility.

The media, locals seem to think, are the real instigators of the new enforcement. Recent news reports on Mexican television and in the Associated Press focused on this border’s sieve-like qualities, and the attention got the government scared–of bad press, not terrorism–and so the government had to make a statement. If the media will just go away and shut up about it, things will slide back to normal soon.

Rick Page is the proprietor of the Lajitas store, and he’s so uninterested in talking to me about the closings that he won’t even turn away from the freezer he’s restocking (although to be fair, it’s the most comfortable place for miles).

“You should just write about how beautiful it is out here and how friendly everyone is and let this other stuff die down.”

Word around town is that Page has seen a sharp decline in his Bud Light sales since the crackdown. Cut off any definable segment of this community from access to the store for more than a day or two, and Rick Page would see his beer sales plummet.

The nice lady at Panther Junction in the National Park wants to be clear: U.S. Border Patrol had expressed a policy by which any crossing from the Mexican side–returning from Boquillas, or arriving for work–is in violation of the law because neither Lajitas, nor Santa Elena, nor San Vicente, nor Boquillas, are official ports of entry. The closest POEs are Del Rio downstream, and Presidio up. The fine is $5,000, and the roads to either Del Rio or Presidio, on the Mexican side even more so than the U.S., are torturous.

The nice lady couldn’t comment on the likelihood of actual enforcement, but it’s not like Border Patrol was stationed there 24/7. In any case, the point, at the moment, was academic. The Boquillas jonboat was out of commission, the water was too high to wade, and so there was no good way to break the law at Boquillas anyhow.

On the upside, she said, the rain had gotten the snakes out and moving, and I’d have a good chance of seeing some really nice reptiles. Lions and bears, too. A mountain cat had just been spotted in the grove where the Cattail Falls Trail splits off from the Lower Window Trail. If you see a cat, said the nice ranger with her hands up in the air, make yourself look large, don’t run, don’t act like prey.

I camped at Juniper Flats, up in the basin, above The Window, and had one of those standing-on-a-planet-swimming-amongst-the-stars moments so memorably delivered in the Big Bend. Those moments in which the very concept of a political border–of a meaningful line in this sand–stands revealed in its absurdity. One of those moments, of Abbey-inspired confidence in the primacy of desert logic over human meddling, brought to us by the fine folks at the National Park Service, and to be frank, now and again, by our drug money.

I stashed my jerky in the steel bear box, but there were no bears out this night. I didn’t even see any snakes, which was OK, because I’m afraid of them too.

The Mexican citizens of Paso Lajitas who cross the river to work are most affected, followed closely by the schoolchildren who cross to learn. To cross legally, they’ll have to drive over four hours of dirt roads up to Ojinaga, cross into Presidio, then an hour and a half down Highway 170, over the big hill, to Lajitas, and then back again at night. Several families have already moved up to Ojinaga, to make the trip more bearable.

Garza says that the “enforcement operation” of May 10 was prompted by intelligence indicating that “as many as 170 individuals” were crossing at Lajitas every day.

“I can’t tolerate that level of activity on a portion of my river.”

After May 10, when 21 arrests were made, Terlingua CSD superintendent Kathy Killingsworth told the Alpine Observer she “did not notice any significant drop in student enrollment in the month of May,” but the paper analyzed attendance records and found a 60-percent increase in absenteeism during the week after the raid.

In mid-June, Terlingua resident Patricia Kerns organized a human rights workshop for locals. Maria Jimenez, director of Houston’s Immigration Law Enforcement Monitoring Project, and Fernando Garcia, director of El Paso’s Border Network for Human Rights, arrived to speak to some 40-odd residents, who expressed a consensus that the area demands a legal border crossing. That idea received a wet towel in the June 13 edition of The Presidio-Ojinaga International, as reporter Dan Keane outlined the 40 U.S. and Mexican bureaucracies with fingers in the approval process for a new Port of Entry.

The headlines in that day’s edition: “Legal crossings a long way off, officials say” and “Immigrant dies in desert near Sanderson.”

Frank Deckert, Superintendent of Big Bend National Park, is somehow candid and circumspect at the same time. For years, he says, the Park has cooperated with Customs through a “memorandum of agreement” regarding tourist crossings within the Park’s boundaries. He has had recent discussions with Border Patrol regarding these issues, he says, and hopes to negotiate some sort of agreement that would return things to the way they were before May 10. So far, happily, the new priorities have had little affect on his domain, because so far it has been summer, and summer is not his park’s most populous season.

So far there have been no arrests made and no fines levied within the Park boundaries, but policy-wise “it’s still a little sketchy, I guess,” Deckert says.

Garza sees no sketchiness: “I have nothing going with any entity at the moment to discuss that type of crossing. Crossings right now have to be done at a designated point of entry.”

These closings, Garza says, are nothing new. The crossings have always been illegal, and if they’ve been poorly enforced in the past, that’s merely the consequence of prioritizing available resources.

Lajitas boatman Jose Armando “Gordo” Rodrigues Puentes, according to his Marfa lawyer, was finally deported in early July, after almost a month in an El Paso detention facility.

Border Patrol recorded another seven arrests during a second operation on May 24. F

rther operations, BP reports, are “li

ely,” just as long as people keep breaking the law.

During the last weekend of June, Border Patrol stopped a tractor trailer in Sierra Blanca, headed east on Interstate 10, with 8,600 pounds of pot, about $7 million worth.

And me, I’m headed up to Presidio, with plans to cross the border into Ojinaga–remembered fondly for its clay-oven bakery and cheap Mennonite cheese and the camarón cocktail at La Fogata–with hopes of finding a bar with cold Carta Blanca and a TV tuned to tonight’s World Cup match be-tween Mexico and the U.S.

On the road up, the fear strikes again, and I begin to worry whether or not this is such a good idea. If the U.S. loses, certainly, there’s a good chance my Carta Blancas will be free. But if we win?

If history has taught us one thing, it’s that only fools underestimate the passions of futbol fans.

I cross the border legally, without incident, and spend the afternoon walking around. La Fogata is gone. I ask about where I might watch the match, scheduled for broadcast at 1:30 in the morning, only to be told that the bars will be closed by then.

So I check into a hotel near the square and spend the evening sipping beers from an ice chest, watching three hours of pre-game hosted mostly by puppets, and finally the contest itself, which the U.S. wins 2-0, despite being pretty consistently outplayed.

When it’s over, there are no war cries down the hall, no explosions in the streets, no Federales battering down my door looking for a sacrificial gringo. It is in fact one of the quietest nights I’ve ever spent in the border country, and I fall asleep wondering, as I so often do out there, just what, exactly, I’d thought I was afraid of.

As this issue of the Observer went to press, former Houstonian Brad Tyer had just entered Travis County.