Progressive Primers

This past Halloween, two neighbors who live on opposite sides of the street and vote opposing political tickets strung an undecided-voter piñata up on a pulley system between their houses. The red, white and blue figure dangled above traffic. After polling trick-or-treaters on their preferred candidates, the neighbors on their respective porches either cheered and tugged the undecided voter closer, or frowned at the parents waiting on the sidewalk. All in good sugar-charged fun. As I approached the McCain-favoring house, I knew what my 5-year-old and her friend, who happens to be the daughter of our Democratic state representative, were likely to say. “Obama,” they shouted together.

The woman wearing Sarah Palin specs didn’t miss a beat. “Okay,” she said, “then you have to give me some of your candy.”

As we left the house, my daughter asked about the encounter. “Well,” I said, “that lady is worried that if Obama becomes president he’s going to take money from people who have a lot and give some to people who don’t have so much.”

“Like sharing?” my daughter said.

“Yeah, like sharing.”

Tales for Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children’s Literature

“Why is she worried about that?” But by then we had arrived at another house, this one with a howling, headless woman in the yard, so I didn’t have to reply.

Campaign hysteria aside, the answer to my daughter’s question, like so many asked by children, is complicated. Already she infers insights about how the world works based on factors that include, but are in no way limited to, the way her parents rant at the newspaper, the way we celebrate holidays, the skin color and sex of the person who pushes her down on the playground and that of the person who helps her up, the plastic tchotchkes that I buy or refuse to buy, and, the editors of Tales for Little Rebels would argue, the books on her shelves.

Edited by Julia Mickenberg and Philip Nel, Tales for Little Rebels is the first anthology of radical children’s literature published in the United States. Mickenberg, an associate professor of American studies at UT Austin, previously wrote Children’s Literature, the Cold War, and Radical Politics in the United States, which covers some of the same territory. What differentiates Tales for Little Rebels is how it explores the inherently political nature of kid lit through an expansive collection of examples. In his foreword, folklorist and scholar Jack Zipes claims that the late arrival of such a book is no accident. According to Zipes, whose research on fairy tales explores the ways in which metaphors teach essential socialization skills, “We tend to repress the crucial issues that children need to know to adjust to a rapidly changing world. We tend to repress what is at the heart of the conflicts that determine our lives. We have tried to ‘nourish’ children by feeding them literature that we think is appropriate for them. Or, put another way, we have manipulated them through oral forms of communication and prescriptions in print to think or not to think about the world around them.”

Lest parents and potential purchasers fret over the ethics of politicizing their kids through literature, Tales for Little Rebels presents assurances that it has always been so. Children’s literature posits a balance between order and disorder, good and evil, reality and fantasy, even sense and nonsense, and as such it has always been and remains political in nature. And to appropriate Zipes’ words, if ever there were “a rapidly changing world” to which children require adjustment, we’re living in it.

Is this book sufficient to counter shelves full of empty educational calories like Kellogg’s Froot Loops! Counting Fun Book, stacks of manically marketed movie characters and princess plots based entirely on being pretty?

Maybe not, but its historical exploration of the political nature of children’s books and its reading lists are welcome and necessary tonics. And stories, poems and plays from the likes of Carl Sandburg, Dr. Seuss, Langston Hughes and lesser-known socialist lights, which earnestly attempt to provide progressive answers to the questions children ask, are godsends.

A few days after Halloween, I was cleaning house with the “help” of that same 5-year-old. She asked me who was singing on the radio. “Prince,” I told her.

“He’s who you marry, right?”

“Well, not exactly,” I said, lamely. Should I try to explain the Artist Formerly (and currently) Known As … ? Talk about a complex answer.

That night I sought help from the anthology, beginning with Girls Can Be Anything, written by Norma Klein in 1973. The story follows a girl named Marina and her friend Adam through a series of make-believe games in which Adam keeps insisting that Marina play his sidekick-the nurse, the stewardess, and finally the First Lady. With the help of her parents, Marina gives Adam examples of women who do the same things men do, and suggests that the two of them take turns. They both become presidents and alternate piloting one another to important speeches. My daughter asked to hear the story again the next night, its equal rights narrative and kid-friendly illustrations already developing more traction than a hundred of my not-so-subtle hints that princesses don’t actually do much of anything very interesting anyway.

I kept reading. She liked all of the princess stories, but less of a hit in my book was Jay Williams’ “The Practical Princess.” While the heroine, Bedilia, does manage to think herself out of a few jams, she’s still an elevated beauty who marries the prince. And in an equally sexist turn, the story’s men and boys are generally hairy and useless. More nuanced is the anthology’s final princess installment, “The Princess Who Stood on Her Own Two Feet.” In this tale, by Jeanne Desy, the princess must deal with the prince’s discomfort at her being taller than he is. So she pretends that she can’t stand. Through a series of situations in which she gives up qualities and skills and possessions that are important to her, eventually even her beloved dog, this princess finally learns that what matters is being true to herself. She turns runaway bride, tries out some spells and digs a grave by hand. She does marry a prince eventually, but at least it’s the right one.

The book contains eight sections: “R is for Rebel,” “Subversive Science and Dramas of Ecology,” “Work, Workers, and Money,” “Organize,” “Imagine,” “History and Heroes,” “A Person’s a Person” and “Peace.” Even with the specific political and historical context that Mickenberg and Nel provide for each chapter, the book’s arrangement feels fluid, as if any of the stories could fit in any of the sections-a sort of mimetic device that illustrates the ways in which all of these issues are interwoven.

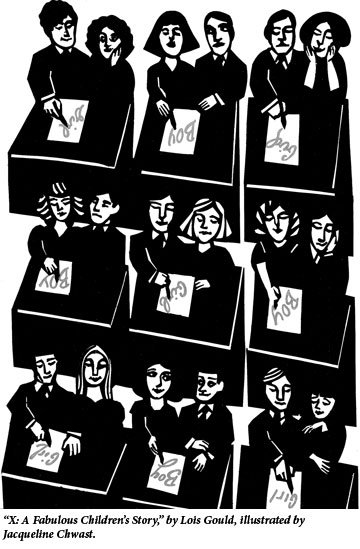

There are some clunkers and a few inclusions that presume on academic interest more than they inspire reading. Take this bit from The Socialist Primer:

“Is this a spider? It is.

“What is its other name? The Capitalist System. Has he got an ant in his web? He has. What’s the ant’s other name? Workingman.”

Still, the excerpts from radical primers in the “R is for Rebel” chapter show how easily ideology can be distilled down to the ABCs. And more important than any particular ideology, as the editors explain in their introduction, is to acknowledge that ideology has been worming its way into children’s literature for as long as there’s been any. In 1690, the New England Primer‘s entry for “A” read, In Adam’s Fall / We Sinned All.

As I wrote this review, the Texas State Board of Education was holding a contentious hearing about a proposed requirement that public school science teachers teach the weaknesses of evolutionary theory, so Mickenberg and Nel don’t need to convince me that ideology influences science. But for the unconvinced, the book’s “Subversive Science” section includes Red Ribbons for Emma, a story about the ways in which corporate pollution affects Native American communities, and William Montgomery Brown’s 1932 Science and History for Girls and Boys. While “Bolshevik Bishop” Brown’s biography is fascinating, his writing is all over the place. Regardless, some passages ring inconveniently true, as in: “We asked science to help us produce wealth, but we never asked it to help us to share or, as we say, distribute it. What we need is the help of science all round in planning to produce the physical and cultural necessities of the world and to place them within the reach of all.”

In contrast to the Bolshevik Bishop’s pontificating, Charlotte Pomerantz’s The Day They Parachuted Cats on Borneo: A Drama of Ecology spins a tragically funny tale out of what happens when good scientific intentions-in this case, spraying Borneo’s villages with DDT to kill mosquitoes-end up destroying a culture’s ecosystem.

And speaking of culture: While the widely circulated list of books supposedly on Sarah Palin’s ban-list was at least exaggerated and at worst a fabrication, the place of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone at the top of the American Library Association’s list of most challenged books for five years running proves how books that question societal norms-even wildly popular books-are received by the self-appointed gatekeepers of normal society. The problem with the Potter book is apparently that it “encouraged children to disobey authority.” In other words, books about real mavericks get into trouble.

The kind of trouble that Tales for Little Rebels encourages mostly involves the ubiquitous childhood question “why?” Such questioning doesn’t turn out so well for little Paul in the book’s selection from Fairy Tales for Workers’ Children, titled “Why?”. As the fat matron of the poorhouse where the boy lives answers, “Everything is as it is and therefore it is right.” This sounds a lot like “because I said so,” which comes out of my own mouth now and then. And while this might be a fine response when we’re talking about staying out of the street or picking up toys, it’s not good enough when we’re talking about poverty or civil rights or war. But Paul doesn’t give in to incuriosity, even when “the question stands between me and all the other people who do not ask the question like a big wall and this makes me so lonesome.”

This is not what we would call a happy ending, but it’s an ending I want my kids to hear. And Paul eventually learns that other people are asking questions too, and that if he listens hard he might be able to hear them.

Poet Eve Merriam is included here writing about the characters in her own Independent Voices collection: “What appealed especially was their gumption-not hesitating to look and act like a fool-and the pinch of mischief along with the high purpose and morality in each of their personalities.”

She was talking about specific historical figures, including reformers Lucretia Mott and Frederick Douglass, to whom her verse pays tribute, but she could also have been talking about the essence of good old-fashioned dissent, the necessary friction that comes with imagining what could be, instead of just accepting what is. I like to think she is also describing the kind of parenting this book advocates. Sure, the characters in these stories break rules, but that’s because something has been shown to be more important than rules. Like equality, clean air, peace and imagination.

When I was a kid I owned a copy of The Important Book, by Margaret Wise Brown, known best for Goodnight Moon. I hated The Important Book. It presented everyday objects like spoons and trees and then defined the most important part of each. I remember thinking, but what if I don’t think that’s the important part?

Innocuous as it seems, The Important Book staked a clear claim about what children should think about how the world works. A book in which everyone drives her own car, or every character is white, does the same thing. It says, “This is normal.” One could say that Tales for Little Rebels makes the claim that every book is An (Equally) Important Book. By introducing kids (and their parents) to a wide range of forgotten and overlooked texts addressing progressive themes, and by provoking a closer look at what the books we already own imply, Mickenberg and Nel have done parents and kids alike a truly important service. ■

Jenny Browne is an assistant professor of English at Trinity University and the author of three collections of poems, most recently The Second Reason (University of Tampa Press, 2007). She is also mother to 2-year-old Harriet and 5-year-old Lyda Rose, who were, respectively, a rock star and a queen for Halloween. They asked for a red fish for Christmas, and got one.