Change, Anyone?

Seeking higher ground in Denver.

It was Tuesday afternoon, the second day of the Democratic National Convention, and I was squatting by a sofa in a leased warren of hospitality suites in a brick building near Denver’s Pepsi Center, sipping a local brew and munching a deep-fried “beef cigar” courtesy of the nonprofit group Media Matters. On the couch was University of California-Berkeley linguistics professor and Don’t Think of an Elephant author George Lakoff, best known in political circles for his work exploring the ways in which the parties use metaphor to frame debate.

Lakoff was fiddling with an ill-functioning iPhone and bemoaning the “idiot” environmental movement’s incomprehension of the full insidiousness of the Bush administration’s latest assault on the Endangered Species Act when he was distracted by the banner headline on a television tuned to CNN: “Dems Don’t Attack McCain.”

The extent to which Democrats in Denver would take the fight to Republican nominee John McCain was, of course, one of the convention’s prefab themes, one story line among many whose minutely observed consideration provided grist for the cable news machine’s mill. Would they or wouldn’t they? When? And with what effect?

It wasn’t these questions that hijacked Lakoff’s attention so much as the headline itself, the trumpeting, on a news program, that something hadn’t happened. Which is a tempting metaphor for the convention as a whole.

It’s long been fashionable to dismiss the parties’ quadrennial coronation ceremonies as exercises in pure stagecraft, devoid of meaningful drama and overstuffed with canned speechmaking. Network television’s hour-a-night coverage is properly premised on the judgment that little of the newsworthy variety actually takes place.

Well, yes and no.

Ought the citizenry feel compelled to follow every twist and turn of the rules-of-order arcana that govern a political convention’s progress? Of course not. Need anyone but the helplessly starstruck bother tracking the private-party appearances of Ben Affleck, Ashley Judd, Kanye West, and Darryl Hannah? Hardly. Can even the most motivated chronicler be expected not to nap through the perfunctory early-program pronouncements of the Formerly Republican Mayor of Nowheresville and the heartfelt testimony of an Uninsured Mother of Howevermany? Please. Could anyone, including 15,000 journalists, possibly give a damn about the logjammed logistics of navigating a temporary bureaucracy seemingly designed specifically to frustrate every last already frustrated ambition of 15,000 journalists? Lord, no.

But for 4,440 delegates, and especially for those newly motivated first-timers who’d clawed and cajoled their ways from primary to caucus to state convention to this plateau, there was meaning aplenty.

Just being in Denver meant they were participating, and in the act of participating they were helping fulfill their obligation to democracy, which has always promised—even when it was lying—to function of, by, and ultimately for the people. Just feeling obligated to democracy implied that democracy was a thing that might reward the attention.

For the city of Denver, for the emergingly relevant Mountain West, for attending press, for partying celebrities, the 45th Democratic National Convention may have meant many things, many only marginally related to the foregone conclusion of the business at hand: the nomination of Barack Obama as the Democratic candidate for president.

But for the delegates, and for thousands of other citizens who had no obvious business in Denver other than to count themselves present at this historical marker on the road to we know not where, it was mostly about being there.

As the convention approached, four distinct narrative threads fluttered in Denver’s thin air, taking the shapes of questions awaiting answers: Would the aggrieved outskirts of Hillaryland a) fall into line (and how they hate this sort of language) behind the presumptive (presumptuous, they claim) nomination of Barack Obama, or b) let emotionalism and hero worship derail the Democrats’ desired show of unity?

Would Bill and Hillary Clinton a) swallow their pride and endorse Obama with grace and conviction, or b) let the Clintonian sense of entitlement overshadow the actual candidate at his own party?

Would the high-risk grandiosity of Obama’s open-air acceptance speech at Invesco Field a) be regarded, as ostensibly intended, as a gesture of openness and come-all inclusion, or b) give Republican character assassins a broader brush with which to paint the candidate as a self-aggrandizing egoist?

And finally, would some yokel a) attempt something tragic, or would the New West b) mind its manners?

To dispense with the last (and least) question first: both. Despite an imposing police presence and sporadic outbreaks of unsightly but largely isolated protester-police conflict (see YouTube), it was a relatively calm week in Denver, an appealing city with its presumably best foot forward.

That didn’t stop a four-man gang of Aryan yahoos from suburban Aurora from getting arrested with a stash of guns, drugs, walkie-talkies and bulletproof vests late Monday night. Under questioning, one turned on his buddies and suggested a vague plan to assassinate Obama at his acceptance speech Thursday night. Authorities ultimately dismissed what they called “the racist ramblings of three meth heads” and concluded that the men posed “no credible threat.” The news, whatever it was worth, didn’t make much splash nationally. Racist groups suspect the boys were framed.

The answers to the first three questions, as best could be determined from inside the bubble, turned out to be highly qualified “maybes.”

While nobody seemed to quite believe poll numbers suggesting that 30 percent of Hillary supporters were prepared to vote Republican in November, it wasn’t difficult to find evidence that a vocal pro-Hillary contingent had crossed a little-known land bridge into vehemently anti-Obama territory. Just a week before the convention, hardcore Austin-area Hillary delegates maintained an anything-could-happen hope that Clinton could somehow—perhaps through a floor petition that never got off the ground—emerge from Denver as the party’s like-it-or-not veep nominee, or even top-of-the-ticket nominee.

Similarly inclined PUMAs (“Party Unity My Ass”) marched through Denver Tuesday and tried to convince the same media they insisted had treated their candidate unfairly (while giving Obama a free pass) to write about Obama’s supposedly faked birth certificate and Party Chairman Howard Dean’s undemocratic anointment of the lesser-qualified candidate. (See www.justsaynodeal.com for more such sore-loserdom.)

Curiously enough, the smallish PUMA march started ahead of schedule, leaving a large and confusing gap between itself and the much larger anti-war/progressive-issue-grab-bag march that followed.

That gap only got wider when the PUMAs turned away from downtown near the terminus of the route and wandered to a halt at the end of an access alley on an urban college campus. As several would-be marchers struggled to catch up, the talk turned—again—to conspiracy. Who had instructed the angry women (and a few men) to start early, confusing media coverage and minimizing turnout? Who had directed the dead-enders for Hillary down a low-profile route culminating in a literal dead-end? Had the culprits, one joked—I hope—been wearing Obama buttons?

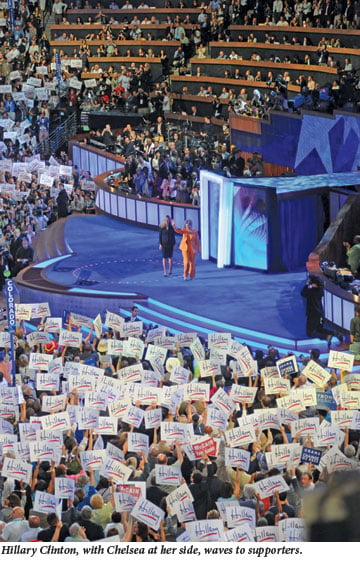

Hillary’s knockout Tuesday speech, followed by Bill’s on Wednesday, demonstrated the perilous political water the Democrats’ most dynamic duo was asked to navigate.

Hillary had to put party first on Tuesday. She had to do so in service of a candidate she has reason to feel is less qualified for the party’s nod, and she had to do so convincingly under the gaze of a media throng ready to pounce on any sign of insincerity as a symbol—God forbid—of party division. Further, she had to do so with her neck weighted by a ring of inconsolable supporters who either could not or would not reconcile themselves to the plain political fact that sometimes candidates—sometimes even the best candidates—lose.

“I want you to ask yourselves,” Hillary asked in her Tuesday night swan song, “were you in this campaign just for me?” Like so many others at this convention, it was a rhetorical question, and the only responsible answer was no.

On Wednesday morning, Clinton called a meeting with her pledged delegates and encouraged them to redirect their support to Obama. On Wednesday afternoon, midway through the traditional roll call, Clinton arrived to recommend nominating Obama by acclamation.

For most delegates, that did the trick. The motion passed, and afterward El Paso delegate and soon-to-be-former Democratic National Committee Member Norma Fisher Flores, a committed Hillary supporter, struck a note of practical reality.

“I won’t cross party lines,” Flores said from her seat on the floor. “If you’d asked me last night, I might have felt differently, but we cannot have another eight years of a Republican in office.”

Still, Flores was clear that not every member of the Texas delegation shared her pragmatism. Despite the doneness of the deal, there was nothing approaching a Texas consensus for Obama.

“Even when I get back to the hotel tonight, I’ll be talking to delegates,” she said. “What part of [party unity] don’t people understand? At this point, we just need to get over it, like she asked us to.”

Sitting next to her, Fort Worth state representative and Obama delegate Marc Veasey added a line that sounded well worn: “It’s not about the personality, it’s about the issues.”

Could Bill Clinton, still the Democrats’ most powerful personality, come to terms with that?

His Wednesday night speech established that the former president remains the modern party’s foundational rock star, the uncouth Elvis to Obama’s cool Miles Davis, and it contained the hard-to-misinterpret line: “Everything I’ve learned in my eight years as president and the work I’ve done since has convinced me that Barack Obama is the right man for this job.”

(Sure, you could parse that statement to include the implied possibility that there’s a better woman for the gig, but at least Bill tried to put the best face on the delay of his familial dynasty, which is more than you can say for the snarling PUMAs, who ultimately managed to express their disappointment without pulling the whole house down on the Dems’ heads.)

Finally, regarding Obama’s Thursday night acceptance speech, there’s little that hasn’t already been said, except that even a Clinton should be wary of trying to upstage a man with 84,000 adoring fans and a phalanx of fireworks at his disposal. Among the attendees there seemed a remarkable sense of unity, an articulated sense of purpose, a reasoned call to service, and only a few well-meaning but slightly nervous “Dear Leader” jokes. That Obama is a remarkable speaker is stupidly obvious. The question is whether he’s anything more than that.

To supporters, and probably a few fence-straddling Hillary preferrers, Obama said what they wanted to hear, particularizing his promises and engaging a sense of civic responsibility. He countered the fear of radicalism with his elevation of regular people, the suspicion of exoticism with heartland Americana, and curiosity about whether he can throw a punch with a series of jaw-cracking uppercuts to the Republican regime.

To those inclined to doubt Obama, the spectacle probably looked like just another spectacle, or worse. I’m just waiting for the right-wing 527 ad, a 15-second spot of nothing but 84,000 Obama supporters shaking the stadium with chants of “SÃ, se puede!”

The general critique, though, is fair: Obama has a bit of the blank slate about him, a talent for representing many different aspirations to many different people. As the post-speech commentary exhibited, people heard what they wanted to hear in those 45 minutes.

I heard that there were American promises to be kept, and broken promises to make whole, and that government is a thing that might conceivably be conceived of as giving a shit about those kinds of things.

What did the convention mean for Texans?

For San Antonio state Sen. Leticia Van de Putte, it meant a chance to bask in the limelight of her appointment as one of three female convention co-chairs, gaveling Wednesday night’s proceedings to order.

For veteran Waco Congressman Chet Edwards, whose district includes George W. Bush’s Crawford ranch, it was an opportunity to revel in his new public status as a man who can keep a secret—the secret being his not-so-stealth appearance on Obama’s vice-presidential shortlist—and the enjoyment of whatever perks come with high praise from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who advocated Edwards’ nomination.

For 27-year-old Obama delegate Michael Flowers, it was the culmination of a crash course in political engagement that began when he heard Obama deliver the keynote address at the 2004 convention in Boston and subsequently went to work for his campaign, earning his delegate status with a promise to blog the convention for the folks back home.

For Clinton alternate Ather Pasha, a 59-year-old Muslim from East Bernard in Wharton County, it was a chance to commune with a 45-member national Muslim caucus, and a particularly timely opportunity to correct some of the media stereotypes that have lately attached to his faith.

And for non-delegate Victoria Lippman, a first-generation American with Haitian roots who now serves as executive director of the Round Rock Volunteer Center in Williamson County, it was a chance to be present at a historic moment, no matter that she had to get there on her own dime or wait for her daughter to start kindergarten before she could fly out.

Early on in the campaign, her 8-year-old son had asked why there were no black presidents.

“So for me, getting Obama elected means a whole lot more,” Lippman said. “There’s no way I wasn’t going to be there.”

For down-ballot candidates hoping to bodysurf the Obama wave into office, the prospects remain unclear. Obama has put 13 paid staffers on the ground in Texas, fewer than many state Dems would have liked, and 50-state strategy or no, his campaign seems disinclined to fight for Texas.

Strategists hoping to pick up the five legislative seats Democrats need to reclaim the Texas House on Obama’s coattails will have to work and wait, and hope invigorated primary voters remember to come back in November.

Back in Austin on Saturday night, with Denver already receding into memory, the world had seemingly moved on. McCain had strategically chosen Friday, the day after Obama’s historic acceptance speech, to announce his vice-presidential running mate, Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, a surprise choice whose implications were already dominating the news cycle. Contemplation of that move would soon segue into coverage of the Republican convention in St. Paul—at least to the extent that coverage of Hurricane Gustav would allow.

Taking a break from trying to figure out what it all meant, or if it had meant anything at all, I paddled a canoe out onto Lady Bird Lake to watch the bats emerge from their lairs on the underside of Ann Richards Bridge. As the tourist barges puttered and an estimated 1.5 million Mexican free-tailed bats streamed along the tree line and off into the dusk, I drifted within earshot of a middle-aged man sitting in a kayak. He asked me if I’d been following the news about the Russian invasion of Georgia.

I told him I hadn’t much, that I’d been preoccupied with the convention in Denver.

<p

He looked disappointed and said something about bread an

circuses, a phrase from the Roman poet Juvenal’s Satire X, describing the tendency of decadent peoples to choose food and frolic over freedom, their susceptibility to cynical leadership’s false populism.

More specifically, my floating fellow told me, NATO was sending troops to Georgia, Vladimir Putin was warning that military action there would be considered an act of war, and while 84,000 facile friends and I had been watching Stevie Wonder deliver Barack Obama, signed and sealed, World War III was cranking up on the Russian Federation’s southern border. He’d known something odd was up, he told me, the minute he awoke on 8/8/08, the day the Beijing Olympics started and Russian tanks rolled into South Ossetia.

What, I asked him, did the date have to do with it?

“They say the people who rule the world are into the occult,” he replied. He exhibited special ease with the use of the word “they.”

I mentioned the pleasing symmetries celebrated in Denver last week. Hillary Clinton’s speech on the 88th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Barack Obama’s acceptance address on the 45th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech. Denver’s hosting of the Democratic National Convention 100 years after it last hosted same, in 1908, when the party nominated William Jennings Bryan, another gifted speaker and populist rhetorician, and 100 years after the birthday of Lyndon B. Johnson, whose Voting Rights Act helped pave Obama’s way.

The man in the kayak looked at me meaningfully and said wasn’t it interesting, all those anniversaries bundled together like that, and held his hands out, spread his fingers, then meshed them together like gears.

He looked up at the bats and marveled at their numbers, living in such confined spaces, doing nothing but sleeping and breeding and eating bugs, and assured me that ultimately “it” was all about population control.

He told me it didn’t matter who nominated whom—there would be no election come November, he believed. The timing of this hot new cold war was no accident, he implied.

“You know how long the average American memory is?” he said. “Fifteen minutes.”

I didn’t question his statistic; I took his point. He wasn’t buying hope, and he wasn’t buying change. Democracy, he’d decided, was a sweet swallowed by suckers. I didn’t know if seven years of George W. Bush had done that to him, or maybe too many nights watching 9/11 conspiracy videos on YouTube, but I didn’t want to believe him. It was too easy to think that Denver meant nothing.

I wanted a new metaphor.

Another canoe slid by, paddled by two young women, in the bow and stern, with a little boy sitting in the middle. The boy looked my direction and said loudly, apropos of nothing: “I’m tired, and I’m going home.”

I was getting tired, too, and the water looked deep and dark out in the middle of the lake. So I took my leave of kayak guy and followed the little boy back toward solid ground.