Golden Days and Olden Ways

There’s no Chisos Basin, no Santa Elena Canyon, no Mule Ears in Texas’ Big Thicket National Preserve. Unlike Big Bend National Park, the only other United Nations International Biosphere Reserve in Texas, the Thicket entertains few visitors. Blackwater swamps, hardwood bottoms, and longleaf pine forests thick as cobwebs don’t make for best-selling coffee-table books.

Besides being uninviting, the Thicket is plain dangerous. Of its nearly 1,000 species of flowering plants and ferns, the forest shelters four types of carnivorous plants. In addition to its 186 species of migratory and nesting birds, the swamp is home to alligators and all four groups of North America’s venomous snakes. Panthers and black bears drank from its myriad creeks into the 20th century.

Although its name implies an endless bramble tangle, the Thicket is a varied landscape. Longleaf yellow pines occupy much of the low, rolling hills to the exclusion of other growth. A walk across the bare ground beneath the giant pines, their branches forming a striated canopy overhead, recalls the sense and scale of medieval cathedral.

Dubbed “the biological crossroads of North America,” the Thicket comprises elements of the Florida Everglades, the Okefenokee Swamp, the Appalachian region, piedmont forests, and the open woodlands of the Coastal Plains. Other areas resemble tropical jungles found in the Mexican states of Tamaulipas and Veracruz.

It’s an easy place to get lost.

“The paths of Indian hunters and wild beasts were long the only roads through this wilderness,” the 1940 Works Progress Administration guide to Texas states, “and even the Indians avoided straying far from these beaten trails.” In 1542, the Spanish conquistador Luis de Moscoso marched west from the Mississippi River toward Mexico. Upon reaching the Big Thicket, he turned his army around, declaring it impossible “to traverse so miserable a land.” During the Civil War, service-dodging Texans hid out among the hardwoods. Confederate Army conscript details hunted the fugitives, resulting in occasional skirmishes.

The Thicket’s inhospitality protected it from encroaching development time and time again. Until the post-World War II boom years, its heart remained an isolated pocket of old traditions.

Big Thicket People: Larry Jene Fisher’s Photographs of the Last Southern Frontier chronicles that fading way of life. Fisher’s 1930s-era black-and-white photographs of East Texans living off the land are reminiscent of Walker Evans’ 1936 portraits of rural Alabama tenant farmers in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. As opposed to the tenant farmer’s squalor, however, Fisher’s Thicketers seem more satisfied. They aren’t working the land for an absentee landowner. They’re working it for themselves.

“Many practices that [Fisher] documented in notes and photography, such as tie hacking, stave making, chimney daubing, turpentining, and sugarcane milling, had their roots far to the east in places where such practices had largely slipped into oblivion,” C.E. Hunt writes in his opening essay. “Fisher witnessed and photographed these activities as part of daily life-not as exhibitions or curiosities but as an integral means of making a living in the big woods.”

As do modern-day Shaker and Amish communities, 1935 Thicketers lived archaic lives in a backwater of the American mainstream. They grew or killed their own food, dug wells for water, and built mud-daub chimneys with the help of neighbors. As exemplified in Fisher’s photo of a pomaded boy holding his pet fox, wilderness was civilization.

Fisher enjoyed shooting subjects on their porches. In the time before air-conditioning or even electricity for fans, Thicketers occupied their porches most evenings while the house cooled. They did chores like shelling peas or churning milk. Visitors stopped by to talk. Fisher’s photo of an old woman smoking her pipe captures the region’s front-porch culture.

Thicketers earmarked rooter hogs to denote ownership and then released them into the wild, a practice known as free-range grazing. The semiferal beasts fattened themselves off the unfenced land until the stockman rounded them up. Unlike the classic West Texas dynamic between horse and cattle on open prairies, Thicketers relied on trained dogs to work hogs in the thick woods. In one Fisher photo, a woman feeding her pig wears makeup and neatly combed hair. The Thicket received few visitors; an appointment with the photographer was a special occasion.

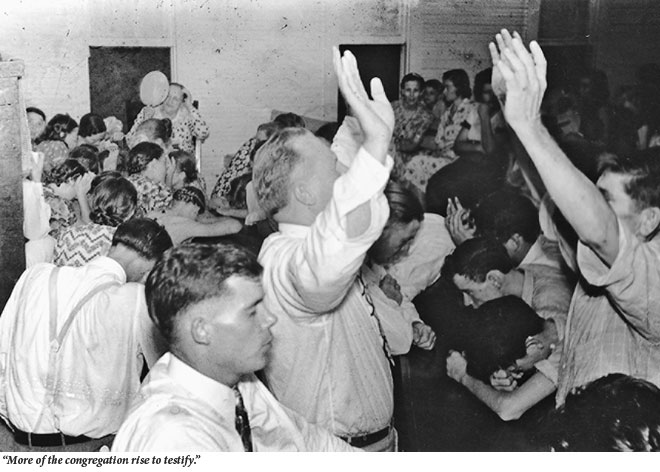

Besides front-porch socializing and hunting parties, Thicket residents congregated at fundamentalist churches. In a sequence of shots, Fisher captures a preacher moving from the pulpit to the congregation, thrashing his hands in the air. Overcome with emotion, a woman stands to “testify.” Soon, most of the congregation is standing with heads back, arms raised, and eyes closed. The fundamentalist churches believed that possession by the Holy Spirit should occur repeatedly.

Although predominantly covering the Thicket’s white community, Big Thicket People also portrays Alabama-Coushatta tribe members and working blacks. The Alabama-Coushatta’s Thicket roots date back to the early 1700s, and the tribe’s 4,600 acres near Livingston comprise Texas’ oldest American Indian reservation. In one Fisher photo, a pretty young girl wearing a large, beaded necklace smiles, holding a baby for the camera.

From its antebellum cotton plantation days, East Texas has been home to a high percentage of the state’s black population. Fisher portrays men in the act of turpentining, a labor-intensive practice that distilled fuel from raw pine sap. Workers slash the pines with special tools in a herringbone pattern, not acknowledging the camera.

Post-World War II pop culture has often expressed a yearning for “simpler” times gone by. Country music stars sing about life on the family farm as if it were a lost Eden. Fisher’s pictures underscore the brutal reality of self-sufficient rural life. Overall-wearing men bow their backs over fallen timber, trying to carve out a niche in the semitropical wilderness. Women in homemade dresses can beans at a counter. Somber-eyed children stare from a two-room clapboard house where three generations of family members reside. Flipping through Big Thicket People in an air-conditioned room with a glass of filtered water puts the past in perspective.

Fisher’s photos were neglected for nearly 50 years, until they were unearthed for a 2000 exhibit. The landscapes they portray are striking. But they communicate even more poignantly a social network, a sense of community interdependence now long gone, and not just from the Thicket.

Stayton Bonner is a writer and musician living in Austin.