A Lot of Nerve

The Army's deadly VX waste is burning in Port Arthur

Above: The Rainbow Bridge in Port Arthur.

Once again an impoverished Texas neighborhood, in this case in the town of Port Arthur, has become the disposal point for hazardous waste, only this time the waste is potentially so lethal that a drop the size of a pinhead can kill.

A chemical-weapons facility in Indiana is destroying obsolete weapons containing VX nerve agent, producing caustic wastewater that the Army is shipping to Veolia Environmental Services for incineration. The Army has claimed the waste is no more dangerous than kitchen cleaners. But when environmental scientists began looking at the disposal process, they found scary scenarios. The “neutralized” waste still contains some VX, and the incinerators might not destroy all of it. There are no monitors on the incinerator smokestacks to sound the alert if it isn’t eliminated. And VX components in the water could reconstitute in shipping tanks under certain conditions, endangering lives along the transportation route.

Several environmental groups, including Texas Sierra Club, the Chemical Weapons Working Group, Community In-Power Development Association of Port Arthur, and individuals in Indiana and Port Arthur are trying to stop the shipments. They filed a notice of intent to sue, and the Army volunteered to halt shipping until the issue was heard in court in mid-July. Despite the admission by an Army representative under oath that VX nerve agent is present in the wastewater, a federal judge in Indiana ruled in August that the shipments to Port Arthur could continue. Environmentalists plan to appeal the decision.

Meanwhile, the groups gathered in Austin on August 23 to urge that regulators halt the shipments administratively. A spokesperson told the Associated Press later in the day that state regulators had assured Gov. Rick Perry the incineration isn’t “endangering public health or the environment.” Nonetheless, after reading about the waste shipments in the media, the EPA’s Environmental Justice Division has started to look into the matter.

The court case is the latest chapter in the long and tortured saga of the Army’s attempts to shed large quantities of extraordinarily dangerous chemical weapons, many of which became obsolete almost as soon as they were produced.

The Army has been trying to dispose of VX for decades by various means in various locations. Some was incinerated on remote Johnston Island in the Pacific, where the army documented the unintentional release of nerve agents after incomplete burning. The U.S. signed the international Chemical Weapons Convention in 1997, bringing a new timetable and sense of urgency to VX disposal. Most recently, the Army tried to ship the processed waste, known as hydrolysate, to Ohio, and then New Jersey. In Ohio, citizen groups opposed the shipments. In New Jersey, the Army insisted the waste was safe enough to be dumped into rivers-until a study by the EPA revealed the waste could harm aquatic life. After public uproars, both states rejected the disposal plans. Citing “lessons learned” in a candid admission by an Army spokesman that a new approach to disposal was needed, the Army tried a new tack: stealth.

In spite of existing law requiring notification and input from affected communities, the Army decided to forgo public notice this time. Informing few besides the mayor of Port Arthur, who didn’t tell his constituents, the Army inked a contract with Veolia Environmental Services for $49 million and began trucking VX residue through eight states to Port Arthur. Veolia is a unit of Paris-based conglomerate Veolia Environnement SA.

It wasn’t long before community activists and environmental groups in Indiana and Texas sniffed out the gambit. Whistleblowers inside the Army’s Newport Chemical Agent Disposal Facility alerted the Chemical Weapons Working Group that the waste was on the move.

“This was the most covert, underhanded approach to disposal in the history of the disposal program,” says Craig Williams, executive director of the group, which has tracked chemical weapons and their disposal for about 20 years.

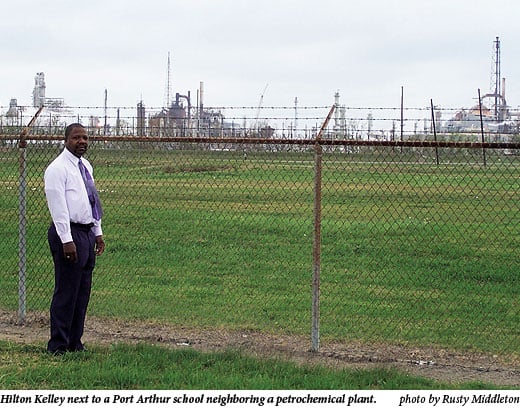

Hilton Kelley, an activist and executive director of the in-power association in Port Arthur, says, “Port Arthur is surrounded by chemical plants and is one of the poorest and most polluted communities in America. This VX waste is yet another threat to the people here who have to live with this every day.”

West Port Arthur wears a brilliant necklace at night, but there is nothing glamorous about it. Glaring, unremitting illumination from tank farms, gushing smokestacks, and bizarre, malignant-looking containment vessels from 72 chemical plants and refineries virtually surround the town. With a few exceptions, such as one bank and City Hall, downtown Port Arthur is an urban wasteland. Rows of slattern, abandoned storefronts slowly are disintegrating. At midday during the week, there are few cars and almost no pedestrians. Out in the neighborhoods, sagging houses gape open to expose weeds growing inside. Anybody with the means has fled the pollution, grime, and mind-numbing ugliness for “ABH,” anyplace but here.

The whites who stayed have mostly abandoned the west end of town, leaving it to blacks and Hispanics who are among the poorest in the state. Port Arthur consistently places among the top 10 most-polluted areas in the country. Politicians and activists often speak of environmental justice, which in Port Arthur means the tendency of heavy and especially polluting industries to locate in poor neighborhoods, as an abstract social problem. But here is the stark face of it-a dirty, derelict community with an air of disease and morbidity.

A 2003 survey by researchers from the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston found that people in the Beaumont-Port Arthur area had more disease, particularly respiratory; ear, nose, and throat; and skin conditions, than people in the Galveston area. Anecdotes abound among Port Arthur residents about friends and relatives who died early because of cancer or respiratory disease.

Kelley, 47, says several of his classmates either have cancer or died young.

“When they told me that Veolia does not have a monitor for VX on its stack or any community ambient air monitors, I just could not believe it,” he says. “How could they not have them? It’s disgusting to know that all across America, when you mention Port Arthur, Texas, that it’s considered the toxic dump site of North America. It’s disgusting to know people are turning their backs on little children and old people and letting them stew in toxic waste.”

Outraged by the secretive deal cut by Port Arthur Mayor Oscar Ortiz, Kelley accused him of being “willing to sacrifice people’s health, especially poor black people’s health, for the property taxes these companies are paying.”

Ortiz, who had not read the details of the environmentalist lawsuit at the time, told the Observer, “It’s just wastewater, pure and simple. Hilton Kelley is a clown and a loser just trying to get attention for himself, and Sierra Club is a bunch of environmental wackos.”

The argument over whether the waste is dangerous has its roots in rival interpretations of testing done to detect VX in the end product of the neutralization process. Sodium hydrochloride is added to the VX, and the mix is agitated for several hours. The result is a caustic solution supposedly free of VX. After the revelation that nerve-agent waste was being incinerated near Port Arthur, Veolia attempted to soothe local nerves by taking Jefferson County commissioners, a Beaumont reporter, and others to the disposal facility in Indiana, where they watched waste being tested for VX. None was found. Hence, said the Army and Veolia, no problem.

“Its just wastewater,” says Dan Duncan, health, safety, and environmental manager at the Veolia incinerator.

Yet a recent study of the new testing method used to detect VX was found to be unreliable. The 2007 study, by the Army’s own Edgewood Chemical and Biological Center, recommended discontinuing its use. Maybe it’s not just wastewater.

The study did not surprise Michael Sommer, an environmental chemist, former University of Chicago professor, and consultant in forensic environmental chemistry.

“The problem is with the analysis,” Sommer says. “This isn’t just a homogenous liquid. It has a solid layer and an organic layer. They only test in the inorganic phase. VX can re-form in the organic phase. Think of, say, olive oil and water. The oil floats on the top. When you stick a probe into the middle, you aren’t finding everything that’s in there. In my opinion they the Army don’t use acceptable testing methods. Plus, they are only testing for two chemicals, VX and another almost as toxic, EA 2192. The neutralization process results in many chemicals that are extremely toxic. I don’t think they even know what all is in it.”

In spite of unknowns about the composition of the waste, the Army and Veolia have repeatedly said no VX could re-form after neutralization.

Not so, says Sommer.

“The question is no longer whether there is VX in the waste. It is how dangerous is it, and most importantly, could the VX potentially re-form in its storage tanks? The troubling fact is that VX can re-form under certain circumstances, such as lowered pH, and that’s not just my opinion. The National Research Council has studied the problem and noted the potential for re-formation, but the Army has not adequately researched this scenario. We just know what the Army has told us, and that isn’t much. But we do know that a change from very high pH to a lower or neutral pH creates the possibility of recombination to re-form VX at significant concentrations.”

Another flash point for critics of VX incineration is the lack of VX monitors on the smokestack of the incinerator, or ambient air monitors in the community.

“We don’t need them,” says Veolia’s Duncan. “We don’t do continuous monitoring of individual hazardous wastes. We monitor the emission of things like carbon monoxide and dioxide, and that tells us how well the incinerator is working. Monitoring for VX would be a waste of money.”

Of all the objections made about the VX waste incineration, the monitoring issue has been perhaps the most contentious and emotional.

Neil Carman, a former air pollution expert with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, now works for the Sierra Club. In a court document, he calls the absence of VX monitors “unconscionable” and “especially egregious.”

Carman knows his hazardous-waste incinerators. As an inspector for the state of Texas, he has reported on them, studied them, and climbed all over them, including the type of rotary kilns used at Veolia.

“Veolia could be putting out VX into the atmosphere and not even know, or maybe even want to know it. These incinerators are not 100 percent efficient. They are more like cheap pay toilets,” Carmen says. “Trace concentrations of a broad array of chemicals are frequently detected during periodic incinerator stack tests. In fact, even under permitted, normal operating conditions, Veolia is putting out a significant, harmful amount of emissions.”

Veolia’s incinerator reports more kinds of toxic emissions than refineries, chemical plants, and other industrial facilities report in most years. In 2002, for example, EPA reports show that Veolia released 17,828 pounds of stack and fugitive emissions into the air. The stuff that incinerators put out is mind-bogglingly bad. And that tally doesn’t include smog-producing emissions reported to TCEQ under a separate monitoring system.

“This is a very messy business and a very messy company, and that is just routine operations,” Carman says. Mechanical breakdowns or “upsets” that are common problems with incinerators, he says, release even more toxics into Port Arthur’s atmosphere.

Veolia’s compliance records at TCEQ reveal an extensive list of violations. Since 2002, when the company was known as Onyx Environmental Services, Veolia has been served 67 violation notices and assessed with $57,920 in fines. The company actually paid $24,128 after negotiating the fines down.

Other Veolia incineration plants around the country have had serious problems with mechanical breakdowns and unpermitted releases of pollution.

“It’s ironic and tragic that all this concern over the danger from this stuff is not even necessary,” says Williams of the Chemical Weapons Working Group. “There’s a better way to get rid of it. It’s called supercritical water oxidation. It’s a secondary treatment for the waste that reduces the leftover VX to the vanishing point. The problem is that it will cost them more, and they don’t want to spend the money. I guess they just would rather put people at risk, especially those poor folks in Port Arthur.”

Rusty Middleton is a freelance journalist who has written widely on natural resource and environmental topics.