Memory Bias

I recently learned the hard way that memory is an unreliable narrator. That’s what happens when you try to write a memoir as a group. My sister Liz and I decided to tell the story of our unusual childhood and realized that we should share the narrative with our siblings, Amanda and Dan. We would rely on our memories and ask them to do the same. We disagreed about important facts, but instead of hiding the disagreements or trying to divine who was right, we decided to celebrate the conflicts in the book. After all, we weren’t reporting the story, we were remembering it.

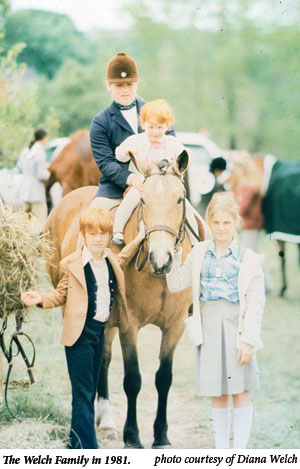

When I was 4, my father died in a car wreck. It was 1982, and though no one else in the family knew it, he was more than $1 million in debt. My mother, an aging soap-opera actress, was diagnosed with cervical cancer a month after his death. She continued to appear on television for three-and-a-half years. Though she lost her uterus, her colon and her bladder, she refused to admit she was dying until the day she lost consciousness in December 1985.

My mom’s denial went so deep that she left no plans for me and my siblings to stay together. My sister Amanda, at 19, was already independent enough to live on her own in an apartment in Brooklyn. My 16-year-old sister Liz bided her time living with a family for whom she babysat until she could graduate high school and escape the bad memories that drooped around our hometown. Meanwhile, I was 7 years old and placed with a family that had no idea what to do with me. And 14-year-old Dan, the only boy, was left basically homeless. The man who had told my mother that he’d take Dan arrived at her funeral holding a tennis racket with a note attached to it that read, “To a good game!” He handed the racket to Dan and, without even a stammer, said he hadn’t known what he was “getting himself into” before he turned around and left. Dan ended up staying with a family we are calling the Hayeses that had a son in his freshman class. Dan lasted seven months in the home before Mrs. Hayes simply had it with him and kicked him out. As it turned out, not so simply.

In light of the scandals involving James Frey and others who wrote fiction and passed it off as memory, there has been a shadow on memoirs. Perhaps our decision to include more than one perspective was a way to beat the skeptics to the punch—by admitting that our memories are ours alone, we thought we’d immunize ourselves to their gripes. Since we were relying on childhood memories, we thought it only fair that we allow the people we wrote about to tell their version. Upon publication, we asked classmates, friends and neighbors—anyone who knew us—to go to our Web site and tell their version. We called their section of the site “Your Stories” and anxiously waited for those people to read the book and share their memories with us. We didn’t have to wait long. The first story came from the family, whom we call the Hayes, that tried to take in Dan.

Dan was not kind to the Hayeses in the book. By his own admission, at the time, he was pissed. “Before the Hayeses,” he wrote, “I had been free.” What he remembered most were the rules: a curfew, a designated homework hour, and no more riding in cars with teenagers, to name a few. To his 14-year-old self, Mrs. Hayes was tantamount to a jailer. A “tyrant” who “scared the crap out of everyone, including her giant husband,” Mrs. Hayes was also, according to Dan, “sort of jaundiced” from chain smoking. Of the day he was kicked out, Dan wrote:

I was just sick of it, so I was up in my room, blaring “Add it Up,” which goes, “Why can’t I get just one fuck, maybe it has something to do with luck …” Mrs. Hayes had complained about the lyrics before—she hated swear words. So every time the word “fuck” came on, I turned the stereo way down, then turned it up again full blast. “Why can’t I get just one.” I kept doing it over and over, blasting it, and turning it down, blasting it, and turning it down.

Mrs. Hayes called Dan to the kitchen, where she was on the phone with Amanda, her face “all red and spitting.” He couldn’t remember what she was saying to Amanda, but Amanda could. “Mrs. Hayes was screaming, ‘I’m so sick of his shit! I can’t deal with it anymore! It’s ruining my family! He’s not my problem! He’s your problem!'” Amanda wrote. “Once she got all of her evil out, she was like: ‘Dan is no longer welcome in this house; he needs to be out. Tonight.’ So, I went and got him.”

When we received Mrs. Hayes’ submission, I was relieved that Dan’s bogeyman from the past, not mine, had reached out first. Regardless, it was thrilling. What would this woman whom we described as a “screaming, red-faced bitch” have to say? Midway through her e-mail, I was floored. “You remember me screaming all the time,” she wrote. “But I remember me crying all the time.” With that one line, she encapsulated everything that excited me about inviting multiple perspectives on my family lore. Her e-mail, nearly three pages long, was thoughtful and honest. “You are right that none of our memories are or can be the same,” she said. “There are some things I thought it would be helpful for you to hear and, for sure, I am feeling defensive.”

Her description of meeting our mother added depth to a familiar image: that of our mother, pale, with a silk scarf around her head. Not sure where her son was, she had come to the Hayeses’ house to see if he was there. He wasn’t. “There was pain and panic in her eyes,” Mrs. Hayes remembered, regretting not having asked in the sick and worried widow. Months later, after our mother’s death, she recalled how her son Brad had told her Dan had nowhere to go, and how she and her husband decided to help out. “We always had a house full of kids, anyway,” she wrote. Her own father had died while she was in high school, so she empathized with our plight.

Her description of meeting our mother added depth to a familiar image: that of our mother, pale, with a silk scarf around her head. Not sure where her son was, she had come to the Hayeses’ house to see if he was there. He wasn’t. “There was pain and panic in her eyes,” Mrs. Hayes remembered, regretting not having asked in the sick and worried widow. Months later, after our mother’s death, she recalled how her son Brad had told her Dan had nowhere to go, and how she and her husband decided to help out. “We always had a house full of kids, anyway,” she wrote. Her own father had died while she was in high school, so she empathized with our plight.

Then things took a turn. Dan was more difficult than Mrs. Hayes anticipated, pushing her and flouting the rules of her home, staying out past curfew, going into New York City without her permission. “I know you resented our rules and me but the rules weren’t unreasonable and actually very typical,” she wrote. “We expected all three of you to go to school, play sports, eat dinner as a family and get homework done. There was always time for TV, playing outside, music and reading. School nights were for staying home and weekends were for going out. Nothing unusual there.”

Though Dan and Mrs. Hayes might disagree, it seems to me that both versions tell the same story. “Memory is a tricky thing,” we warned our readers at the beginning of our book. “Our interpretations of other people’s actions are locked in a time and place—an eight-year-old who has lost her parents sees the world in a much different way than that same girl twenty-five years later. The same is true for a sixteen or twenty-year-old-girl, or a fourteen-year-old boy.” Imagine, then, the difference in perspective for a middle-aged mother of two who invites a recently orphaned teenager into her home and the perspective of that traumatized kid? When I asked Dan how reading Mrs. Hayes’ version of events affected him, he said, “I feel unburdened. Now she knows how I feel, and now I know how she feels. And we never have to talk to each other again.” Being the only one telling the story weighed on him—he found it freeing to let everyone have their say.

Mrs. Hayes didn’t just comment on Dan’s experience. She offered a defense of my guardians, a conservative family we called the Chamberlains. I lived with them for six years, and it was not fun. Like a rock in a shoe, I was apparently such a nuisance that they eventually had to shake 13-year-old me out. Thankfully, they sent me to live with Amanda, who at 25 was, in my opinion, a far better mother than Mrs. Chamberlain ever could have been, because we understood each other. I didn’t comprehend the way the Chamberlains did things and lived in fear of setting off Mrs. Chamberlain, who had a way of making me feel incredibly small.

The big sticking point for us Welches was that the Chamberlains considered my siblings a bad influence and prevented them from visiting me for most of the six years I spent in their home. Mrs. Hayes shed some light on that, as well.

“I recall Mrs. Chamberlain calling us one night,” she wrote. “You had all gone to pick up Diana and bring her out for ice cream. It was a school night and you were asked to have her back by 8. She wasn’t returned until 10 or 11 because you brought her to a party. … Is it really possible that everyone who attempted to help all of you had come straight out of a Dickens novel? As badly as I feel for all of you, I also feel very badly for the Chamberlains. I personally feel that a lot of what was written about them needs to be taken with a grain of salt.”

What was written about the Chamberlains was not flattering—I recalled the evening when, to punish me for bad table manners, I was made to eat dinner out of the family’s dog bowl, and the afternoon my mouth was scrubbed out with soap for another infraction. I was called ugly, just to be put in my place. And there was Mrs. Chamberlain’s seemingly endless refrain: “Who do you think you are?”

But Mrs. Hayes is right—my memories should be taken as everyone’s memories should: as my own. Perhaps one of these days I’ll get that rush of adrenaline when I see the Chamberlain name in my e-mail inbox, and with one click will open a portal to my past as experienced through another perspective. Until then, my memory will have to serve alone.

Diana Welch is a former reporter for the Austin Chronicle. The Kids Are All Right is her first book.