Forrest Bess: An Artist Laid Bare

A version of this story ran in the July 2013 issue.

Above: Forrest Bess with his painting Untitled (11A), in his home/studio, Chinquapin Bayou, near East Matagorda Bay, Texas, 1958. The Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston.

“Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible,” on display at the Menil Collection in Houston, contains two shows. One presents Bess’ paintings, the other presents the biographical residue of his life. The approach contains a challenging paradox: While Bess’ seemingly simple paintings are primed to find new fans, the portrait of their maker makes the paintings difficult to look at.

The Menil Collection’s Clare Elliott curated the careful selection of paintings by Bess, a Bay City bait fisherman who in the 1950s and ’60s showed his work through the prestigious Betty Parsons Gallery in New York (Parsons’ gallery also represented Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still and Mark Rothko). The show’s biographical component is an installation by artist Robert Gober, originally created for the 2012 Whitney Biennial as part of the similarly conceived Bess retrospective “The Man that Got Away.” Gober’s contribution consists of three display-case vitrines filled with documents and ephemera relating to Bess—a diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic and self-created “pseudo hermaphrodite” who devised elaborate theories about gender unification. The letters, books, journals, magazines and photos collected by Gober explore—often graphically—the impulses and ideas behind the work on the walls. They also unintentionally raise questions about the line between explication and exploitation.

Bess was born in Bay City in 1911. As a child Bess took a few art lessons from a neighbor, but he was largely self-taught as a painter. Salutatorian of his high school class, Bess briefly studied architecture at Texas A&M University. Architecture was a compromise; he had wanted to study art, which his parents apparently deemed too feminine a pursuit. Bess transferred to the University of Texas after a couple of years, and though he never received a degree, he read widely in school: philosophy, mythology, mathematics and psychology all interested him. After leaving UT, Bess worked in the oil fields for a few years, making occasional trips to Mexico and, according to one account, watching Mexican muralists including David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera at work. When World War II commenced, Bess enlisted in the Army Corps of Engineers. There he designed camouflage and eventually reached the rank of captain.

Bess had experienced intense visions since childhood, but he didn’t start painting them until an Army psychiatrist suggested it as a form of therapy. Bess needed therapy in the wake of what was characterized at the time as a nervous breakdown following his confession of homosexuality to a fellow soldier, who promptly beat him with a lead pipe, causing, as Bess explained in a letter to his San Antonio friends Rosalie and Sydney Berkowitz, “a caved-in skull.” Bess recovered from his injuries but, as Elliott’s curator’s essay suggests, the physical and psychological repercussions of the event likely triggered the artist’s psychotic break.

After the Army, Bess set up a studio in San Antonio for a brief period before moving into the isolation of his family’s fishing camp near Bay City, eking out a living fishing for bait to sell to other fishermen. Bess’ camp was on a stretch of land so remote that it could be reached only by boat. In his down time, Bess painted the visions he frequently saw before falling asleep or just after waking. As the exhibition catalog explains, Bess made small black-and-white sketches to record the images. As long as he had the sketch, he said, he could recall the vision perfectly and make multiple paintings of it. Bess saw his artistic role as a matter of transferring to canvas the visions that came to him.

The paintings Bess made from those visions are intimate, emanating a quiet, thoughtful power. Their small size was at odds with the grandiose abstract expressionism of the day, and their faithfulness to Bess’ original sketches runs counter to the expressive and investigatory painting of the other artists in Parsons’ stable.

Bess’ biography, too, is unlike those of his contemporaries and peers. His story has much in common with those of “outsider” artists, but such stories of self-taught, often rural artists with psychiatric issues usually involve some sort of intermediary between the artist and the art world. The scenario usually goes something like this: Working in isolation, the idiot savant/mystic visionary/obsessive mental patient, ignorant of the art world and his or her own greatness, is discovered by an impresario/exploiter. Bess’ story is different. While he suffered from mental illness, he was also highly intelligent and capable. He was the agent of his own discovery. In 1948 he sold 40 of his older, more representational paintings for $10 apiece to finance a trip to New York to scout galleries and find a dealer. Parsons’ was one of the galleries he visited. He showed her his work; she liked it, liked him, and wound up giving him five solo shows between 1950 and 1967.

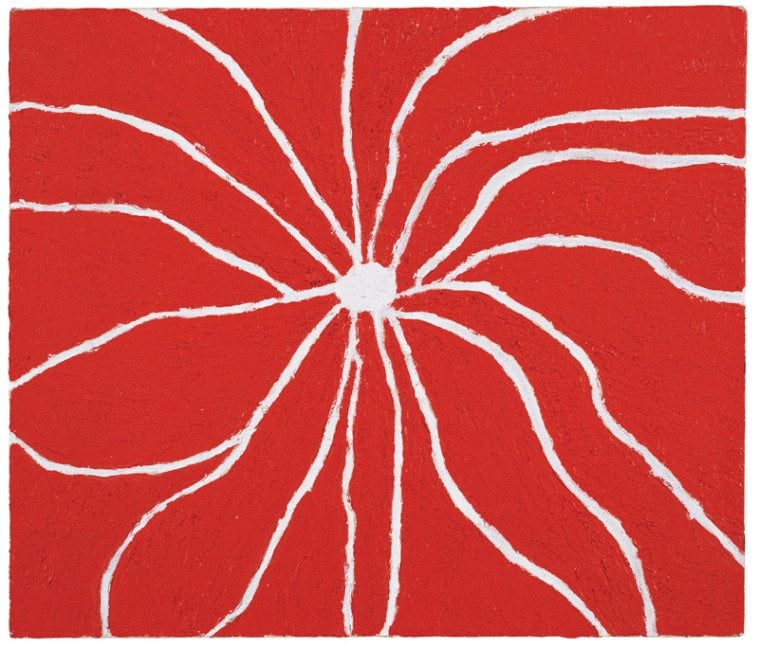

Bess’ oil paintings are wonderfully tactile, the paint sometimes mixed with sand. I don’t know if it’s sand that gives Untitled (The Spider), 1970, its texture, but the striking red painting has a slightly spiky surface beneath the white lines snaking out from the white circle at its center. Some of the show’s works still feature Bess’ appealingly clunky handmade frames. Bess didn’t believe in the niceties of mitered corners. In some cases museums have mimicked the construction of Bess’ frames, but those tidy constructions lack the gravitas of the weatherbeaten lumber that Bess likely scavenged.

Untitled (No. 5), 1949, has just such a frame, which looks like it was culled from a post-hurricane scrap pile. The paint it surrounds seems buttered on the canvas: a jetty-like bit of gray extending into an expanse of lime green and, in the foreground, a reddish-orange vertical form radiating against a green ground. It has the feeling of a figure against a seascape, but could also be read as phallic. The colors are amazing. One wonders what it must have been like to be visited by such intensely hued visions.

Untitled (No. 11A), 1958, has a regular pattern of blue and white marks that optically vibrate against each other, creating a kind of horizon against a blood-red sky. Dedication to Van Gogh, 1946, delivers its own optical buzz with parallel orange and green lines zigzagging to a horizon line. The brush strokes allude to Van Gogh’s manic mark-making.

Other works contain forms or pseudo-hieroglyphic symbols that seem laden with hidden meaning.

Bess imbued many of his paintings with a contemplative mysticism, but that trait doesn’t invariably make for great paintings, and the show contains several clunkers. Untitled (No. 11), 1950, may have been an important vision for Bess, but its muddy edges and dull blue-and-brown lozenge-shaped form in the center don’t work for the uninvolved viewer. If only No. 11 could have sacrificed itself to save a better painting when, in 1961, Hurricane Carla’s 16-foot storm surge took out Bess’ house and all the work in it.

Overall, though, Bess’ paintings are engaging, even if the ideas ostensibly behind them are less so. Bess wrote an elaborate thesis (since lost) explaining his theory of uniting the male and female within himself—surgically—with the goal of regeneration and immortality through the union of opposites. The thesis was a kind of scrapbook illustrated with clippings from books and medical texts as support. Bess kept trying to convince Parsons to present the thesis alongside his work, but Parsons, understandably, declined. On their own, Bess’ paintings worked within the art world; appending Bess’ writings would have been more than a little off-putting to many collectors. It’s much easier to just relate to the paintings visually without getting dragged into the messy and unsettling ideas behind them. It’s also likely that Parsons was trying to protect Bess from himself.

Gober has no such qualms. He seems to want to put it all out there, to force us to face the totality of Bess as a human being, to try to fulfill Bess’ dream of integrating his thesis with his paintings.

In lieu of the lost thesis, Gober’s vitrines contain letters from the artist, books about sexuality, and magazine and journal articles. Bess sent letters to President Eisenhower, Carl Jung and sex researcher Dr. John Money presenting his theories of male/female unification with a kind of evangelical zeal. He struck up a lengthy correspondence with art historian Meyer Schapiro, whom he had met while staying with the Berkowitzes at their Woodstock, New York, home. Schapiro looked at art within the larger social, political and cultural contexts in which it was created. Among the pages from Bess’ letters to Schapiro on view here, one includes a cut-out illustration of the “tree of life” growing from biblical Adam’s groin. There are no letters from Schapiro, but judging from accounts I’ve read, he seems to have been patient and kind to Bess. In an article about Bess for Hyperallergic, John Yau asserts that Schapiro likely dissuaded Bess from castrating himself by sending the artist a copy of a Greek play in which the hero dies after castration.

One vitrine contains a 1982 Texas Monthly magazine article about Bess, while another contains a copy of a 1963 Vogue with a piece about Betty Parsons. There is a photographic portrait of Parsons, and multiple photographs of Bess, including some fairly straightforward photographs of Bess standing naked prior to his self-surgery. Then there’s the black-and-white Polaroid snapshot of the hole Bess cut into the base of his penis with a razor blade. Having steeled himself with drink, he was trying to create an opening in “the bulbous section of the urethra” big enough for another man’s penis to penetrate. He would repeat this self-surgery at least once more during his lifetime.

Many such Polaroids were reproduced for a paper Dr. Money wrote and titled “Three Cases of Genital Self-Surgery and Their Relationship to Transsexualism.” Reproduced in a grid, they carry a creepy medical-manual vibe. The publication is on display in one of Gober’s glass cases, but Bess is not identified in the text.

(Money was a well-known sex researcher who ended his career in disgrace. Through the Gender Identity Clinic he established in 1951, Money worked with a surgeon on the first U.S. sex-change operations, becoming a “leading expert” on gender identity and hermaphrodism, which is why Bess contacted him. Money thought sexual identity was a result of nurture, not nature, and remained undetermined until age 2. Money’s downfall came after he was contacted by the distraught parents of twin boys. One boy’s penis has been burned off during a botched circumcision. Money advised the parents to castrate the boy and raise him as a girl, and to never tell the boy the truth. Money touted his strategy as a success in spite of the fact that the child independently decided to dress as a boy at a young age and later committed suicide.)

Gober’s work exhibits a coldly clinical fascination with Bess that feels short on empathy and long on voyeurism. Maybe you can argue that shielding viewers from the darker aspects of Bess’ mental illness is a kind of closeting. I don’t know. But I think there is something sensationalist and exploitive about including that Polaroid.

At the show’s press preview, Gober said visitors can choose to look at the vitrines or not, but that’s disingenuous. You can’t make an informed choice to look or not if you don’t know what’s there in the first place. Difficult material in a museum exhibit usually gets advance notification with a card on a stand at the entrance. The Menil’s restrained approach to labeling is ridiculous here. The mature-content warning is discreetly placed on a wall at the entrance to the show, the small gray text closer to knee level than to eye level. Seriously, are we that worried about seeming uncool and bourgeois?

I saw one guy trying to figure out what to say to his son as they stared at the black-and-white Polaroid of the hole Bess cut just above his scrotum. I have a 4-year-old and a 6-year-old. I’m not worried about them seeing nudity in art, but an up-close-and-personal Polaroid of a mutilated dick is another thing. I wish I’d never seen it, and I used to work at the UT medical school and walk to the cafeteria every day past a research poster with a picture of a gunshot wound to the face. That didn’t bother me as much as the images of Bess’ self-mutilation. What this bright, talented man felt compelled to do to himself is tragic.

“Seeing Things” raises thorny questions for which there aren’t easy answers. Is there a middle ground between obscuring an artist’s identity and laying it bare for all to see? A lexicon in the catalog and exhibition pamphlet, culled from Bess’ letters, explains what Bess’ various symbols meant to him. An upside-down ankh equals “life–dilated urethra,” an eye equals an “orifice, the vulva or subincision,” concentric circles mean “to make hole larger, hole gets bigger.” Several symbols reference the “bulbous section of the urethra.”

Perhaps they make an interesting decoding game for art historians researching the work, but I don’t really want to enter Bess’ head when I look at his paintings. Artists build work out of all kinds of ideas, and most of the time those ideas never clearly reach the viewer. There is nothing wrong with that. Art is more than information. You can’t control how people perceive a work of art, and providing me with a primer to Bess’ mental illness doesn’t help me appreciate his creative work. In this case it diminishes it, turning the paintings into illustrations of psychosis.

Bess’ life needn’t be sanitized for the viewing public’s comfort, but at what point does biographical completism become sensationalism? Would Van Gogh’s paintings be better served by a photo of his mutilated ear displayed alongside? What if the prostitute he supposedly gave it to had the foresight to save the lobe in a jar of formaldehyde? Would that relic deliver real insight?

I love Bess’ paintings, the ways he used paint, smoothing, slathering, stippling, accumulating it in tiny strokes. I love the works’ odd shapes and symbols, their deceptively simple compositions, their otherworldly landscapes. Whatever they symbolized to Bess, as a viewer I find them tranquil and haunting.

Bess didn’t paint during the last years of his life. In 1974 he was committed to a mental hospital and sent to a Bay City nursing home. He died there in 1977 from a stroke. The difficulties of his life were painful and sad. I wish this show had a little more empathy for the man who endured them.