Fall of the House of Craddick

How did the formidable Republican lose his speakership?

There was a time, back in January 2005-four years before his downfall-when Tom Craddick’s political opponents tried to make peace. Craddick was entering his second term as speaker of the Texas House and was telling reporters that he wanted to instill a gentler, less partisan tone in the Legislature’s lower chamber, that he had learned the lessons of his turbulent first session. Craddick had been devastatingly effective in that first session, using a commanding 26-seat majority to push through an ultra-conservative and partisan agenda that included tort reform, spending cuts, and Tom DeLay’s redistricting plan, which led Democrats to flee for Oklahoma on the session’s final weekend. (Craddick responded by calling them “chicken Ds.”)

The speaker’s heavy-handed tactics had already worn thin with most Democrats and some Republicans by the start of the 2005 session. If he was ever going to make his speakership more inclusive, to alter his ways, the opportune moment was perhaps when Rep. Pete Gallego, a Democrat from Alpine, walked into the speaker’s office as an emissary from the opposition.

Although Craddick still led a large majority, there were hints that his political fortunes were shifting. Two months before-in the November 2004 election mostly dominated by Republicans-Democrats had picked up a seat in the House, their first such gain in three decades. Moreover, one of Craddick’s key lieutenants had lost her bid for Congress.

Gallego, a veteran lawmaker and former chair of the appropriations committee, is a natural compromiser. He told Craddick that the Democrats wanted to work more constructively, that they wanted to be part of the legislative process and return the House to the more bipartisan, collegial atmosphere it enjoyed under Craddick’s predecessor, Pete Laney.

The speaker was unmoved. “I don’t care,” Craddick said, according to Gallego. “You can vote yes, you can vote no. I don’t care.” He had a majority, he had his votes, and the Democratic caucus would remain outcast as long as he sat in the big chair.

“It was shocking,” Gallego recalls. “I thought we all cared about the process and the place. I was used to the Tom Craddick who was a member, who was gracious and polite. I was not used to the Tom Craddick who was speaker, who was unapproachable and unwilling to compromise.”

After that rejection, says Democratic caucus chair Jim Dunnam, the majority of Democrats in the House gave up trying to work with Craddick and instead set their minds to taking him out. Democrats would go on to pick up 11 seats in the next two election cycles-enough, this winter, to team with moderate Republicans and end Craddick’s reign.

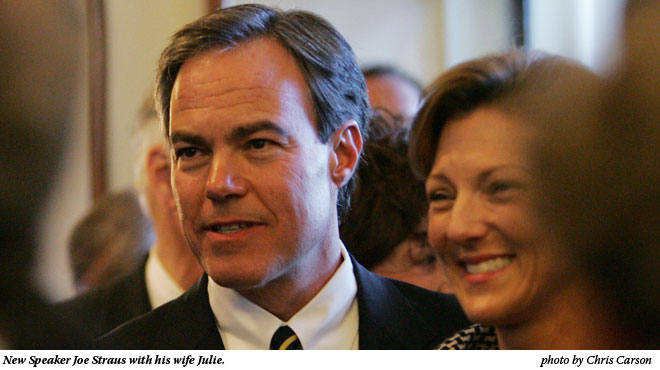

The exchange with Gallego was typical Craddick. It tells you something about a man when even his close friends describe him as “unyielding.” It also tells you a lot about why Craddick was sitting silently at a desk near the edge of the House floor on January 13, just another face in the crowd watching Joe Straus being sworn in as his successor up on the speaker’s dais. Craddick had withdrawn from the speaker’s race in early January after a group of 70 Democrats and 15 rebellious Republicans announced their support for Straus, a San Antonio Republican, ensuring him enough votes to win. Straus is a young moderate who had pitched himself to colleagues as a bipartisan consensus-builder. In other words, the anti-Craddick.

As a politician, Craddick is remarkably straightforward. There was never confusion about his strategy or his goals-no subterfuge or head fakes. He knew what he wanted. If you stood in the way, he would marshal his power and resources, lower his shoulder and plow straight ahead. No deals, no compromises. If you wanted to stop him, you had to respond with equal or greater force.

It was a style that worked well in Craddick’s rise to power. He entered the House in 1969 at age 25 as one of just eight Republicans and, during the next three decades, helped lead the Texas GOP out of the political wilderness. In 2003, he became the first Republican speaker of the Texas House in more than 130 years. But there was a limit to how long Craddick could treat people in such an uncompromising way and maintain his hold on power.

After alienating Democrats with his rejection of Gallego at the beginning of 2005, Craddick estranged moderate members of his own party a few months later. On May 23, 2005, he tried to force through the House a controversial proposal to launch a school voucher pilot program. Vouchers are the pet issue of Dr. James Leininger, a major Republican campaign contributor and Craddick benefactor. Many Democrats and rural Republicans opposed the voucher bill and didn’t even want to debate it. The speaker not only brought the bill to the floor anyway, but dragged uncooperative Republicans into his back office to twist their arms into voting his way.

It didn’t work. That night, for the first time in his speakership, Craddick lost a major vote. In the next round of primary elections in 2006, Leininger-with Craddick’s backing-went after the dissenters. They spent millions to defeat five incumbent Republicans who had opposed the voucher bill. Two lost their seats.

“If you’re trying to build a House of collegiality and when you’re trying to minimize division, I don’t think it’s ever good to go after incumbents. When you do it, you also have to accept the risk when you fail,” says Rep. Sylvester Turner, a Houston Democrat who crossed over to support the speaker. The leader of the so-called Craddick Ds-the dozen or so Democrats on the leadership team-Turner served as the speaker pro-tem during Craddick’s six years in power.

When the next Legislature convened-in January 2007-the level of hostility in the chamber had only increased. Craddick had to fend off several opponents to barely win reelection as speaker. About a dozen Republicans were in open revolt. The challenges to his authority came almost daily. It culminated on the final weekend of the 2007 session when an effort to remove Craddick from the speaker’s chair paralyzed the House. Had it come to a vote, Craddick likely would have been stripped of the gavel. Instead, he asserted absolute control of the chamber and, in an effort to forestall a vote, refused to recognize anyone for parliamentary motions he didn’t approve of. By that point, the House had devolved into farce. It was becoming clear to even partisan Republicans that Craddick’s continued speakership might be untenable.

In Turner’s view, one of Craddick’s mistakes was concentrating power in the speaker’s office. Unlike past speakers, who delegated power to their lieutenants, “Craddick pretty much called the shots, and so he became more the focal point,” Turner said. “If you’re on the other end of it, it’s easy to find who the target is because he was the general and the lieutenant. Don’t make your circle so small that you’re not hearing the voices of many others. I think when leaders do that, then they become very time-limited.

“My advice is always to listen to the heartbeat of the members on the floor. Members have a way of letting you know ahead of time, and you’ve got to listen. If, for example, I come to you, and I say, look, people are really having heartburn on this issue and it’s not just from one party. They’ll vote [on this issue] if they have to, but they really don’t want to. I think sometimes you have to conclude that this is not a measure that should move forward. If you try to force it, it may pass, but it passes with a price. The next [bill] that’s being met with some reluctance, that may pass too, but you pay a price. The third one may not pass. The fourth one may not pass. When it starts getting like that, when things are not passing, it’s almost like there’s been a tear [in the House]. Hard to put that together again.”

For Craddick, it was, finally, impossible.

In person, Tom Craddick doesn’t resemble the domineering political figure described by his critics. He is soft-spoken. On the speaker’s dais, he frequently mumbled, and occasionally stuttered and slurred through his pronouncements. At receptions, he wouldn’t dominate the room so much as be swallowed by it. Physically imposing he’s not-a short, slightly hunched-over, meek-looking man.

Craddick also is a teetotaler. It’s not just late-night drinks that he eschews. He’s been known to attend fund-raisers and not touch the steak. His one vice is about as wholesome as it gets: chocolate. “He’s a good, sound Christian fellow. There’s no reason to ever not like Tom Craddick,” said Warren Chisum, a Panhandle Republican who served as House Appropriations Committee chair last session and is one of Craddick’s closest friends in the House. “He’s unyielding in his goals. But you sit down to talk to him, he’s not vindictive. He understands that you may disagree sometimes.”

Craddick often talked about changing his governing style.. It wouldn’t have required much-a gentler hand at certain times, delegating some power, listening to his colleagues-to remain speaker. The enduring question is, why didn’t he make those changes? Some of his critics thought him incapable of governing differently. “The leopard can’t change his spots,” as Dunnam put it.

That thinking sells short Craddick’s considerable political skills. Rather, it seems he didn’t change his ways because he simply didn’t want to. “If his only purpose in life was to remain speaker, then yes, he could have just gone with the flow,” Chisum said. “That wasn’t his purpose in life. His purpose was to do what was best for the state and grow our economy. That’s the role he chose to play.”

In the end, perhaps, implementing his ideology was more important to Craddick than remaining speaker. He spent six years trying to remold the state in his ultra-conservative image.

His supporters praise Craddick for holding spending down and keeping taxes low, which they say helped fuel the economy. In the early years, Craddick pushed through legislation backed by the corporate interests that had bankrolled his rise to speaker. He passed one of the strictest so-called tort reform laws in the country, limiting lawsuit awards to $250,000. The law has made suing doctors, hospitals and, in particular, abusive nursing homes, much more difficult. He engineered a bill that deregulated tuition at the state’s universities-a measure desired by regents at the University of Texas, who were major Craddick supporters. As a result, tuition at Texas’ colleges has risen an average of 58 percent. At some schools, it has more than doubled.

To close a deficit in 2003, Craddick’s budget cut more than 200,000 kids from the Children’s Health Insurance Program-cuts that were partially restored in 2007, but not before they contributed to the estimated 1.5 million children in Texas who lack health insurance. He passed bills that restricted access to abortion, and he helped institute a constitutional ban on both gay marriage and civil unions. He passed a bureaucratic reorganization of the Health and Human Services Commission that laid off thousands of state workers and privatized several key programs. He blocked nearly any bill limiting air pollution or reducing the greenhouse-gas emissions that cause global warming. Craddick poured precious little new money into public schools.

It’s this record-for better or worse-that will be Tom Craddick’s legacy.