Political Intelligence

Bugs in the System

As Hurricane Ike bore down on Texas last month, employees of the University of Texas Medical Branch-Galveston moved to secure a complex of laboratories containing some of the most dangerous germs on the planet, including Ebola, anthrax, and hantaviruses. Workers disinfected research spaces, destroyed active cultures, and locked the remaining bugs in freezers.

Officials assured the public that all precautions had been taken to ensure that none of the labs’ dangerous contents could escape. The hurricane came and went with no Outbreak-style disaster, but the storm did leave UTMB’s labs without power for days, compromised the lab’s critical negative-pressure safety systems, and once again left critics scratching their heads over how a barrier island, occasionally battered by tropical cyclones, became a center of the post-9/11 boom in biodefense research.

“To my knowledge this is the only BSL-4 that is situated in such an environmentally unstable area,” says Edward Hammond, a biodefense watchdog. UTMB-Galveston has two Biosafety Level Four (the highest such designation) laboratories and eight BSL-3s. A third, much larger, BSL-4, part of the new Galveston National Laboratory, is slated to open in November.

“Even if you believe in the biodefense program, you’ve got to be looking at [Ike] and saying, what … did we do building all this BSL-4 space in a place that you have to shut down once every year,” Hammond says. “There’s a huge scientific and economic price to that.”

The island’s biohazard facilities “came through with flying colors,” said Dr. James LeDuc, deputy director of the Galveston National Laboratory. The buildings suffered only minor damage, and there were no security breaches, he says.

Ike did, however, highlight serious flaws in the system.

A small BSL-3 lab in the basement of the Keiller building was flooded, and sophisticated equipment was damaged. Putting that lab and others in the basement was a mistake, LeDuc says. They will likely be moved once the new facility opens.

Ike also knocked out power and water to UTMB. That left the biohazard facilities without air conditioning-the campus relies on a chilled-water system-and dependent on backup diesel generators. But the generators failed as well, leaving all of the labs without power for at least 36 hours, and in some cases a week or more.

To maintain the ultra-low temperatures in the freezers storing its pathogens, UTMB had to rely on 40,000 pounds of dry ice delivered before the storm.

UTMB’s labs also lost negative pressure, a safety feature that keeps pathogens from escaping, because of the power failure. “[A]ll the labs had been disinfected and all infectious waste destroyed so there was no risk of infection,” LeDuc wrote in an e-mail describing the previously unreported system failures.

But Hammond insists the incident was serious. He points out that when a new BSL-4 lab in Atlanta, which hadn’t been stocked with germs yet, lost power in a lightning strike, the incident was front-page news. “UTMB’s situation was much worse,” Hammond wrote in an e-mail. “They lost negative pressure for 36 hours in a lab holding one of the largest collections of incurable infectious diseases in the world.”

What about the storm next time? The building housing the new BSL-4 is engineered to resist winds of 140 miles per hour and a 25-foot storm surge, according to the EPA. A Category 5 storm, or a strong Category 4, could generate winds well in excess of 140 mph. The 1900 hurricane that nearly wiped Galveston off the map packed winds estimated at 135 mph.

“It’s like a lot of things with these labs,” Hammond says. “It’s low probability on any given day, but if it happened it could be catastrophic.”

-Forrest Wilder

Here’s a thought exercise: Imagine you’re running for re-election in a swing district against a well-funded, charismatic challenger. As the campaign goes on, the press has broken story after story about some of your, ah, questionable uses of campaign money. Election Day is fast approaching. What do you do?

Easy. Attack the reporter who broke the story, of course. Steadfastly refuse to give interviews. And-the coup de grace-sue your opponent, alleging that she didn’t resign from her city council position by the proper deadline to get on the ballot. When a judge throws that case out as ridiculous, appeal the ruling. Wait for result.

If any of that seems ridiculous, you’re probably not Republican state Sen. Kim Brimer of Fort Worth. (Incidentally, if you are Sen. Brimer, I’m still waiting for that call back.)

Brimer represents Fort Worth’s Senate District 10, an area in the middle of a demographic and political transition. The district is 56 percent Republican but is becoming more Democratic. An August poll showed that Brimer had less than 50 percent name recognition in the district.

Democratic challenger Wendy Davis is running an aggressive, media-savvy campaign. She has raised more than $700,000 since her campaign began, of which she’s spent about a third, according to filings with the Texas Ethics Commission. Her attractive, intuitive Web site makes it easy for supporters to contribute and volunteer. And her campaign has missed no opportunity to talk to the media, even using Brimer’s lawsuit to kick her off the ballot to paint the incumbent as corrupt and out of touch.

Whether any of that will make any difference is, of course, up in the air. But Brimer is running an unusual campaign. He has raised more than $1.5 million but spent only about $100,000. Until October 3, just one month before the election, his Web site was listed as “Under Construction.” He won’t talk to reporters. He seems to have put all of his hopes on the rather flimsy attempt to get Davis booted off the ballot.

Meanwhile, the nonprofit group Texas Watchdog revealed last month that Brimer took loans for his 1989 campaign from the struggling Commonwealth Bank, then put off repaying the money until the bank went under. When the FDIC took over the loan, Brimer made more excuses. He said it wasn’t his debt. He pleaded with the FDIC for help. A bailout, if you will.

So if the Court of Appeals in Dallas decides Davis can remain on the ballot-and at press time, the judges had yet to rule-Brimer may be in trouble.

-Saul Elbein

What happens when your base gets wiped out by a hurricane? If you’re Democrat Joe Jaworski, running for Senate District 11, you slog around in knee-high mud for 10 days in Galveston transporting those who didn’t evacuate and trying to rescue your neighbors’ pets.

Then you settle your family in Houston and try to salvage what’s left of your campaign. The Galveston resident and former Galveston City Council member has been campaigning for almost two years against longtime Republican incumbent Mike Jackson of La Porte. Hurricane Ike was a major disruption he didn’t anticipate just 50 days before the election.

Galveston is the Democratic stronghold in a Senate district known for favoring Republican candidates. Now many of those Democratic voters-Jaworski’s base-have been scattered all over the state. For many evacuees, facing the daunting challenge of rebuilding their lives, voting is the last thing on their minds.

Despite seeing his own home flooded and his city devastated, Jaworski is hopeful that he can still reach many of his potential supporters.

“It’s going to take a lot of shoe leather to reach voters,” Jaworski says. “I’ll be going to shelters and working through the Galveston Democratic Party to get the word out.”

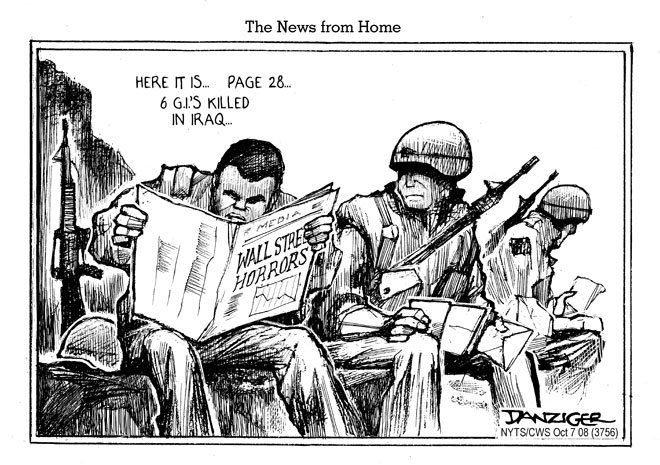

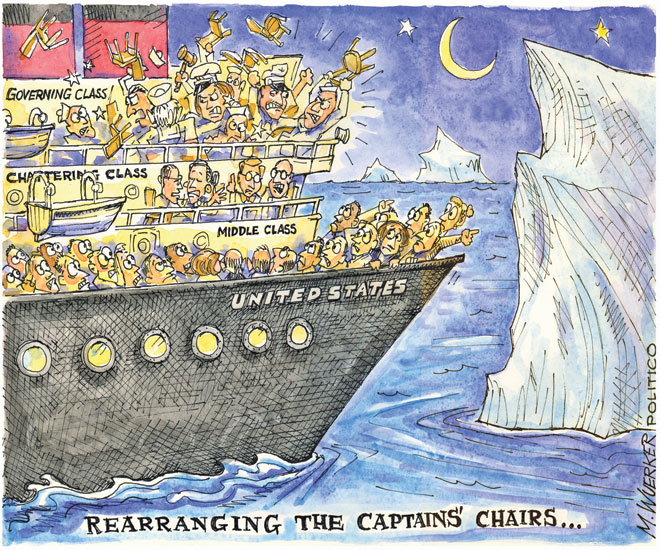

Democratic strategist Kelly Fero says candidates like Jaworski are facing an unprecedented situation, not only regarding Hurricane Ike but also considering the current economic crisis.

“Not only are they trying to rebuild their lives after a devastating hurricane, they are also trying to reach voters who are faced with terrible economic news and the financial meltdown on Wall Street,” Fero says.

How all this will affect the District 11 race is still unknown, he says.

Jackson, the GOP incumbent, who lives in Shoreacres, evacuated along with his neighbors, and his home flooded as well. He took three weeks off his campaign to help coordinate relief efforts in the district.

“The hurricane didn’t hit one party or another,” Jackson says. Many residents of District 11 are still reeling from the loss of jobs, homes, and even relatives, he says.

Fero suggests that diminished turnout typically favors the incumbent, “but during an election with such a huge hunger for change, it’s an unknown.”

That hunger for change translated during the March primary to almost twice as many Democrats at the polls as Republicans in District 11. If an energized Democratic base turns out again in November, it could deliver the election to Jaworski.

The Democratic candidate believes the hardships hitting District 11 voters will propel them to vote-even if they now live in Austin, Dallas or a temporary shelter.

“We need a new, energized kind of leadership,” Jaworski says. “Voters are bitter about the way they are being treated by insurance companies. They paid their insurance premiums on time for years, and now they are being told ‘no’ in a thousand different ways.”

-Melissa del Bosque

While the debate rages over whether the United States’ tougher immigration policies are working, another pressing problem has gone mostly unnoticed: The number of immigrant children being detained in the United States has increased tenfold.

The attorneys who represent these children, free of charge, are struggling to keep up with the skyrocketing number of detainees.

Meredith Linsky, director of the South Texas Pro Bono Asylum Representation Project, known as ProBAR, has been representing children in detention for 10 years. “I would say four or five years ago there were about 50 children in detention,” she says. “We now have 500 children in detention in the Rio Grande Valley.”Linsky says the children range in age from newborns to 17 years old. Most are from the Central American countries of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras. Children ages 14 and under are placed with temporary foster families; the older children are kept in detention facilities.

At her Harlingen office, Linsky works with four other lawyers and five paralegals. They are the only organization in the Rio Grande Valley authorized by the Department of Homeland Security to legally represent children in detention.

“There is a lot of growing pressure on the very limited pro bono services in the area,” she says. “We also work with adults as well, and there are now 4,200 beds slated for adult detainees in the Rio Grande Valley.”

Because of tightening border security, many illegal immigrants are staying put in the United States; rather than risk not getting back into the United States, they are paying smugglers to bring their children to them. Often the children are caught by U.S. immigration officials and wind up in detention along the border.

“The children experience a lot of emotional trauma,” Linsky says. “Some of them have been raped by the smugglers or by the smugglers’ associates.”

With comprehensive immigration reform nowhere in sight for the present, Linsky and other lawyers can expect the number of children in detention to grow.

-Melissa del Bosque