Habitat for Inanity

A Rio Grande fence will separate families, wreck economies, and threaten wildlife, but it won’t stop illegal immigrants.

On hot summer days I would sit atop the water tank on the west side of the stone cabin … watching turkey vultures climb invisible thermals, listening to the soft cooing of white-tipped doves, and gazing at the mosaic of greens that rippled into the distance. Something told me that I should swallow every angstrom of this beauty, commit it to memory, and hold it firmly in my heart.

Arturo Longoria, Adios to the Brushlands

Exhausted, a party of birders slips down the last few feet of a dry arroyo and collapses onto flat, cool stones near the spot where the water begins. Three sleek kayaks and a lumbering canoe sit beached just beyond reach of the licks of a lazy stream, near the tiny town of Salimeño. “We could secede again,” says one of the birders in a tone that sounds only half-joking. He doesn’t need to explain, because all present know the history of the short-lived, combative Republic of the Rio Grande (1839 to 1840). On the floor of the limestone arroyo, giant, fossilized oyster shells shine bright and curvy-edged in the sun. When a song comes from the brush, one of the birders automatically identifies it as “green jay,” and the others assent without missing a beat in a conversation threaded with anger and frustration.

Up and down the Lower Rio Grande Valley, rebellion is in the air. Residents like the birders, and civic officials, are receiving top-down orders from Washington to accept a border fence many do not want, walling off their river. It will reverse new economic ebullience, opponents say, change their border culture, and bring down the curtain on rare critters of which they are stewards, including some found nowhere else in the world.

In Washington, anti-terror legislation is invoked to convince locals they have no choice.

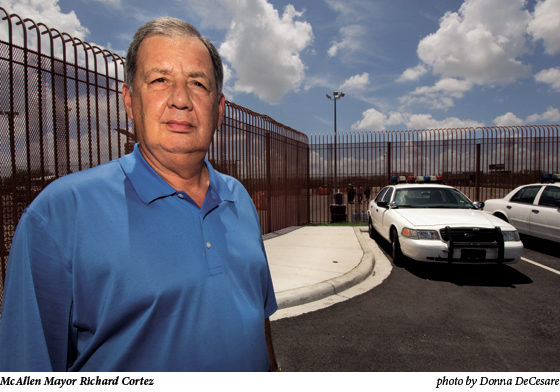

McAllen Mayor Richard Cortez doesn’t buy it. “The law gives them a lot of power, but not total power,” he says. Relations with the Border Patrol, historically friendly, are strained because residents feel deliberately left in the dark about fence plans. The secrecy rankles. “We’re fencing with ghosts now,” says landowner John McClung, president of the Texas Produce Association. “Farmers are opposed because we irrigate almost entirely with water pumped from the river, and need access 24-7.”

If you are envisioning the fence as a high but simple chain-link affair, think again. First, anyone on the river will tell you a “permeable” fence becomes solid in hours as it catches windblown flotsam and detritus. The law says the Department of Homeland Security must install “at least 2 layers of reinforced fencing,” which means clearing a swath some 150 feet wide, locals reckon, to make room for fences, access and maintenance roads. “Think of bulldozing your house,” says Sierra Club representative Scott Nicol, who teaches art at South Texas College in McAllen. “Then bulldoze the ones on either side, too, to get an idea of the width needed for the barrier. Then extend that for 700 miles.” Nicol and others who live along the border know the fence won’t work. They see the undocumented workers who have already braved deserts and jungles and bandits to get this far. “We could have a wall from sea to shining sea, and it wouldn’t make a difference,” he says. Even DHS Secretary Michael Chertoff told Fox News in July that the border “is a much more complicated problem than putting up a fence, which someone can climb over with a ladder or tunnel under with a shovel.”

Tensions grew in May when a government map of the proposed fence emerged at a community meeting. The map shows the wall cutting through a protected wildlife corridor, national refuges, and the University of Texas Brownsville-Texas Southmost College campus (leaving part on the “Mexican” side). The fence slices off public access to historic sites and runs along flood-control levees already in need of repair for lack of funds. (Funds are available, one landowner offers dryly, “at $3 million a mile to build a fence.”) There is no way now to calculate exactly how much U.S. territory will become inaccessible because of the fence. In the Lower Rio Grande Valley alone, the course of the river is one of infinite curves, loops and omegas. A physical barrier that runs for miles must be relatively straight, so in the end significant acreage will be left on the far side of any “border” wall. Is that land effectively ceded to Mexico? Will it become a no-man’s-land? A wall on just one levee in Mission would throw to the far side two restaurants and at least two homes. “I wouldn’t know what country I lived in,” one owner says. The wall would cut off boat docks, a boys’ summer camp, and a small park with picnic tables. It would block access to the La Lomita Mission, after which the town is named. The 19th century wooden chapel was a stop on the historic Oblate Fathers Trail, a small jewel of a place where the faithful leave burning candles at a white altar and the local community is known to pray for rain when it does not come.

With other mayors, Cortez has met with Chertoff in Washington and Laredo, to no avail. The mayors are not indifferent to national security, but believe a fence is not a solution. Texas border congressmen are united against the fence, but Texas’ two Republican senators, Kay Bailey Hutchison and John Cornyn, supported it. Gov. Rick Perry called it “divisive” but has yet to lodge a formal protest to Washington as opponents want. As Cortez puts it, after months of traveling and talking to all the right people, feeling ignored and isolated, border leaders sense the political path is petering out.

DHS defends itself. “We are actively consulting with state and local officials and landowners to decide where it should be,” says spokesperson Laura Heehner in Washington. Local officials say no consultation has taken place. Heehner repeats Chertoff’s caution that communities would have “no veto,” that the “safety and security of the homeland is our primary mission.” The leaked map is only “a first iteration based on Border Patrol assessment of where (the wall) should be,” says spokesperson Brad Benson at Customs and Border Protection headquarters in Washington. Other versions will follow, he says, in consultation with the public, probably after the fiscal year ends in September.

In the Valley, residents are not waiting. “The worst thing we can do is nothing,” Cortez says. Lawyers are being consulted. Environmental activists are enlisting help from national organizations like Defenders of Wildlife, which has said it will join legal action if locals undertake it. Imaginative public demonstrations-100 canoes and kayaks appeared in one protest flotilla-draw crowds. The Texas Border Coalition, an influential group founded in 1998 to give border mayors, county judges, and communities a collective voice, has hired ViaNovo, an Austin consultancy, to “get out the story of our community about the wall, but also about the need for comprehensive immigration reform,” says TBC member Mike Allen. “If Saudi Arabia and Israel can hire consulting groups to tell their story, so can we-it hasn’t been fairly heard in middle America or in Congress.” ViaNovo’s partners include Matthew Dowd, chief campaign strategist for George W. Bush in 2000 and 2004, when he was responsible for targeting and placing $150 million in ads. Tucker Eskew, Bush’s spokesman in Palm Beach during the 2000 election recount and later the president’s Director of Global Communications, is also a partner.

Unlike San Diego and Yuma, where failed resistance to the wall was carried on by a small group of environmental organizations, for an environmental purpose only, here it’s in the hands of a broad spectrum that includes ranchers, civic and business figures, a network of local environmental activists, and long-time cross-border families who consider the fence an insult to relatives and friends. “We’re coming at them from various directions, each in our own way,” says McClung, who is also an avid birder. Efforts are complementary, but not necessarily coordinated.

What’s happening in the Valley is about more than just a fence. By resisting, residents are challenging the kind of post-9/11 federal behavior that is marked by fear, and occasionally is devoid of common sense.

The Secure Fence Act of 2006 mandates physical barriers along 700 miles of the 1,900-mile U.S.-Mexico border to stop terrorists and illegal immigrants. Three hundred seventy miles are set to be completed by December 2008, including 125 to 150 miles in Texas. An extraordinary aspect of another federal law that has gone largely unnoted lets Chertoff, in the name of national security, override any other statute to carry out this mandate. No judicial review of Chertoff’s decisions is permitted, though a claimant may allege a constitutional violation, a route lawyers say has yet to be tried.

This phenomenal power, granted in the emotional fog generated by the specter of terrorism, is contained in the Real ID Act, a rider to an Iraq war funding bill passed in 2005.

The Congressional Research Service has said the law appears to be unprecedented: It gives a political appointee-Chertoff-“sole discretion” to ignore requirements of other federal laws. This section of Real ID passed quietly, as if Congress were unaware of its consequences, or cowering. When a coalition of environmental groups attempted to stop the fence in a delicate estuary near San Diego, Chertoff waived not only the National Environmental Policy Act, sometimes called the nation’s environmental Magna Carta, but the National Historic Preservation Act, the Clean Water Act, National Wildlife Refuge Act, the Federal Water Pollution Act, and other statutes. Near San Diego, a wall made of surplus World War II metal landing mats now reaches through the wetland into the Pacific like a giant cleaver.

Floor debate around Real ID implied the secretary’s special power would be used only in San Diego. But the letter of the law does not restrict its application to San Diego, and there is no time limit on it. After San Diego, Chertoff waived laws near Yuma, too.

Lower Rio Grande Valley leaders argue that the river, a natural barrier, makes a fence less necessary. They may have another argument as well: Under treaties between Mexico and the United States, the river is an international boundary under the aegis of the International Boundary and Water Commission, which holds the right of way on nearby levees where the fence is likely to go. Without the commission’s permission, neither side may erect an obstruction that changes the flow or floodway of the river, or causes erosion, because that in effect is changing a national boundary. Mexico, on record against the wall, is an equal partner in the commission with the United States. Noted Houston environmental lawyer and educator Jim Blackburn recently told a McAllen meeting called by the local Hispanic Chamber of Commerce that while Chertoff can waive national laws, he may not waive treaty obligations.

Blackburn also said accords in the North American Free Trade Agreement obligate the United States, Canada, and Mexico to observe environmental laws and strengthen their enforcement. Ironically, these NAFTA provisions were initially aimed at Mexico, not the United States, which is the one now suspending environmental laws to build the fence.

Should Chertoff waive national laws again, notice will appear in the Federal Register, and objections must be filed within 60 days. Individuals in the Valley and allies in Washington are watching the register closely. A Customs and Border Protection spokesman says progress on the Valley fence is likely to accelerate after October 1, when fencing elsewhere is required to be complete. Many border tracts belong to private ranchers and farmers, who must grant permission for any physical barrier on their property, but landowners are among the most vocal opponents of the fence. Recently, Chertoff said DHS “can’t rule out” invoking eminent domain, a process in which the government may seize private land after providing compensation, even if the owner is unwilling to sell. The political cost of doing so could be high. In these parts, says McClung, eminent domain is a “profoundly offensive” concept. His voice is fuming, but McClung speaks carefully. “There’s an abhorrence of condemnation, an emotional problem with it,” he says.

“It’s a whole lot bigger than the fence,” says Texas Border Coalition member Allen. “This has become the United States of paranoia. And the fence is just a symbol of Congress’ failure to put anything together for comprehensive immigration reform, which is the only way to stop illegal immigration, not a fence that stops someone for two or three minutes until they use wire cutters or a ladder.”

Allen, who helped shepherd McAllen’s growth as CEO of the McAllen Development Corp. for 19 years, remains a leader among those who say the fence is bad for business. This area is one of the most deeply integrated with Mexico and has boomed since NAFTA became law. Since 1996, the McAllen economy has grown at an average of 6 to 7 percent annually. McAllen-not Houston, New York, or Los Angeles-is the No. 1 shopping destination for Mexicans, according to Visa receipts. These Lower Rio Grande counties still register among the poorest in the nation, but McAllen is pulling nearby communities along. A fence in the midst of this effervescence would be like suddenly stationing tanks on the border, says Steve Ahlenius, president of the McAllen Chamber of Commerce. “It messes up the system by doing things like proposing a wall.”

Ninety percent of the Lower Rio Grande Valley is Hispanic, often from families who settled here long before Anglos. Fifty-four per cent of McAllen’s population has relatives on the other side of the river. A local saying goes: “The Valley’s population is 3 million. One million on this side.” Virtually everyone is bilingual. Stand on the bluff in Roma, or on the landing of the hand-cranked ferry at Los Ebanos, or on the lawn of the UT Brownsville-Texas Southmost campus, and look over at what rises like a physical and cultural mirror on the Mexican side of la linea. The river could be a stream running through a single town.

This is hard to explain to the rest of the country, and to Congress. Texas, Ahlenius notes, is already a majority-minority state, but in parts of middle America the number of Hispanics is beginning to grow and change communities. “There’s a mentality of scarcity in the rest of the country, but an attitude of abundance here,” he says. “Opportunities, job growth. Here you can gain market share without having to take it from someone else.” Ahlenius sits at a wide desk with miniature Civil War soldiers deployed behind him-gifts from staff. He pauses.

“I hope deep down it’s not a race issue,” he says. “But it is. We’re scared of America becoming brown.”

Across the hall, Nancy Millar, director of the McAllen Convention and Visitors Bureau, says, “These are quasi-members of our community. People here look the same as those from across the border, and everyone speaks Spanish. Erecting a wall is as good as erecting a ‘not welcome’ billboard.” Millar’s research shows the average visiting Mexican family stays four nights in the Valley and spends $5,300.

She grabs a pair of binoculars f

om a desk drawer and trains it out the third-floor window. “Look, a peregrine falcon,” Millar

ays with excitement. Like many residents of this neotropical flood plain, where 513 of the continental United States’ 730 bird species are found and 330 of some 500 kinds of butterflies, she keeps binoculars at hand. The large falcon is nesting in the cozy curve of a giant “C” on an upper floor of a Citibank building a few blocks away.

It’s not just civic leaders, landowners, and nature lovers who oppose the fence. Nineteen-year old Sally Hart grew up among the tables of Mission’s Riverside Club, a place of weekend barbecues, dancing, community birthday parties, live-music Friday nights, and “home cooking” on the river. Her father, Captain Johnny, has a 38-passenger sightseeing pontoon boat moored outside. Mother Jennifer says they built the place themselves over 25 years of “blood, sweat, and tears.” Sally has her own reasons for not wanting a fence.

“It’s personal to me,” she says, looking over the wooden tables and hanging plants in the patio. “I want this to be a family thing forever.” A junior at Texas A&M, she plans to help her folks run the place and eventually take it over. A fence would run between the club (they live on the lot, too) and the road. Not good for business. “I don’t like to think of it,” she says, looking confused. Memories of a safe and joyous lifetime on the river don’t match perceptions of the place as a front line in the anti-terror war. A few days earlier, a Border Patrol slide show about the fence in Weslaco began with the disturbing, iconic image of the twin towers in flames. Take-home leaflets bear the same picture. Sally recently asked her mother to explain the concept of eminent domain.

“To think it could be taken away, by the government …” Sally says.

Experts like Martin Hagne, a nationally renowned birder and Executive Director of the Nature Valley Center in Weslaco, say the fence will decimate species in a biological area unique in the country. And disappearing wildlife tends to have a ripple effect. “When something is taken out of the equation other things are affected, habitat changes, other things will disappear and we don’t know what,” says Hagne. “Things are connected.”

Down on the arroyo, late in the day, the birders push their boats onto still water that leads quickly into the foaming rio where the river’s limestone skeleton emerges just enough above the surface to be a hazard, forcing the rowers to keep their eyes on the water. The Rio Grande twists wild and clear from Falcon Dam, shared by the United States and Mexico. Cliffs tower, and the water goes calm again. Almost hidden, an elongated Altamira oriole nest sways suspended from a branch in a sugar hackberry tree. The nest is weathered, dark and limp from last season. Lifting gently in the breeze, it looks like an oriental lantern whose flame has gone out. From the right bank, a great blue heron breaks across the water, impressive in size and volume. A white heron stands unmindful in the reeds. On the edge of a midstream island, a spotted sandpiper pecks staccato-like, feeding on insects. Then, a surprise: A bronzed cowbird, fat and feathery, is propelling its body straight up and down, over and over, a mating dance in a mesquite tree for a lady bird who sits quietly on the same branch. Montezuma bald cypress, with multiple spreading roots, ebony, and other trees crowd the shore, making it look dark and cool.

Eleven distinct biotic communities are found along the 170 miles of Valley from Falcon Dam to the mouth of the river. The variety of habitats means a variety of plants (1,200 species) and animal life, making this the most diverse biological locale in the United States. The Atlantic, Central and Eastern bird migration routes converge here, which means you can see birds from remote corners of the continent on their way north or south. And this is the northernmost point reached by some southern birds. Add to that birds found here and nowhere else, and you have one of the most productive bird-watching places in the world.

The tall, riparian forest along the river is where birds like the groove-billed ani, which have flown hundreds of miles, land and rest. Local chambers of commerce jointly produce brochures aimed at international travelers (“Drive on the right”) and support festivals and observation centers that draw thousands in the autumn and spring. Wildlife tourism brings $150 million annually, and jobs, to the Valley. A fence could empty the goldmine.

Without the forest, the gray hawk, for instance, will disappear from here. The wide clearing for a physical barrier means certain migratory birds that stop to rest and gain strength will find no food. Many will weaken and die, or fly off and drop as they try to continue their journeys without nourishment.

By the 1970s, 95 percent of original Valley brushland and forest had been cut down, a process local author Arturo Longoria traces feelingly. In refuges established by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Department, what’s left is protected, and more wild space is slowly growing back as land is committed to butterfly parks and birding centers in Valley towns, painstakingly revegetated, often by volunteers. A protected corridor is being created for animals so they can thrive and reproduce. Millions of acres are protected on the Mexican side, and the wildlife department makes plans jointly with the Mexicans, because plants and animals don’t recognize borders. The corridor is seen as one, binational.

Spotted ocelots, the Valley’s sleek, emblematic, furtive animals, which once roamed over Texas, Louisiana, and Alabama, are now endangered. In the United States they are found only here. There are probably fewer than 100 left. Females make dens for their kittens-one or two a year-in brush like wild hackberry and Texas persimmon; when they are about a year old, the young cats disperse, especially the males, who must roam contiguous wild land for food and protection, claiming their own territory to survive. Naturalists like Hagne say fragmenting the Valley habitat with a fence would doom any comeback of the ocelots, and cripple, probably fatally, the long, slender jaguarundi, too, along with 20 other endangered species.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife has spent $100 million in the last 20 years to acquire refuge land and now protects 90,000 acres, much of it open to visitors. Local residents are deeply invested; they have raised money for land acquisition, too. The aim is a corridor of 134,000 acres. At the Santa Ana Wildlife Refuge near Alamo, Public Outreach Specialist Nancy Brown says, “For 20 years this has been billed as a wildlife corridor, a place where animals might be unencumbered.” With a fence, she says, “You go counter to the very reason for which it was established.”

This is the way Joel Hernandez, a biologist with Pro-Natura, a non-governmental organization that oversees protected areas on the Mexican side of the river, sees the coming of a fence: “Within six months or a year, you’ll begin to see animal life diminishing. You’ll see more corpses on the roads. In three years, the big animals will be fairly gone. If they don’t die because they can’t eat, don’t have their own territory, they’ll die from people who shoot them in the open. You’ll just stop seeing them, seeing certain things. Birds. The place will be more quiet.”

On the river, the birding party-a rancher, two naturalists, and a local DHS employee-spot a red-billed pigeon on a high branch. For two of them, this is a “life bird” event, the term for the first time a particular bird is sighted. In all of the United States, the red-billed pigeon, Muscovy duck, and brown jay are found only within this couple of miles. These birds would not die because of a fence, but you would have to go to another country-the Mexican side-to see them.

Mary Jo McConahay is an independent journalist. Her last feature for the Observer was “They Die in Brooks County” (June 1).