Afterword

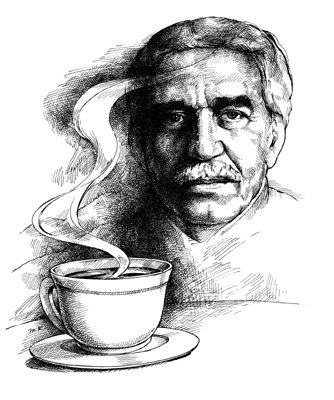

Café Con Aroma de García Márquez

We had just left the Jarocho–you remember that little hole in the wall in Coyoacán, where everyone goes on Sunday to buy coffee? There we were–my daughter Hadita, my friend Charo, and me–just sipping our coffee, when way off in the distance I saw two men and thought one of them looked distinctly familiar.

I said I thought he looked like García Márquez, and they just laughed and told me to stop kidding around. But I just had to find out. So, I started to walk, faster and faster, trying to catch up with those two men. Of course, they realized what I was doing and they turned around and stopped. So I turned around and stopped. (My heart is beating so fast I think it’s going to leap out of my chest.) Then they start walking again and I do the same. Then suddenly they stop again, and turn around and look at me. All I can do is smile, walk up to one of them, and say, “Excuse me for following you, sir, but by any chance are you Gabriel García Márquez?”

“Not by any chance, señorita,” he replies. “By birth.”

You can just imagine how I felt. My whole body was shaking; my legs were numb. And then he says to me, “Allow me to introduce my friend–also a writer from Colombia–Señor Alvaro Mutis.” An elderly gentleman. Very courtly. He kisses my hand. (He’s not a bad writer, you know. He won the Cervantes Prize, the most important literary award in the Spanish language, not long ago.) I turn toward García Márquez and say, “This is like a dream for me. Sir, would you mind if I gave you hug and a kiss?”

“Even two kisses, if you want, señorita,” he says. We talk for a few minutes and then they leave. By then Charo and Hadita have finally caught up with me. “Was it him?” they ask. “Was it really him?”

It certainly was, I say. And we’re going to go follow them. Because by then I see that they have gone into the Parnaso. (You remember the bookstore in Coyoacán that used to be called the Parnaso and now it’s called something else, but everyone still calls it the Parnaso?) As soon as we enter the store, I run up to one of the clerks, and say to him, “Please. Go get me a copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude. And hurry up.” So, he runs after the book and as soon as he hands it to me, I go up to García Márquez and Alvaro Mutis, who by now are standing at the cash register paying for books. “Excuse me for bothering you, sir,” I tell García Márquez, “but would you mind autographing this book? Forgive me, but this is like a dream. You can’t imagine what you mean to me. I learned to read–to really love to read–because of One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

And that’s true, you know, because until then I hated to read. It was such a chore. What I liked about that book was how it reminded me of Villaflores, in Chiapas, where I grew up. All those stories about the Buendías–and all that rain, how it would rain so hard in Macondo, that you could see the colors of the fish flowing through the town. That’s the way it was in Chiapas during rainy season. It would rain and rain and rain, and sometimes we were cut off from the rest of the world for weeks. You would see cows and enormous trees that had been uprooted by the torrential rains, just floating down the river. And then the hungaros–we used to call them hungaros–the gypsies, just like in Macondo. Whenever they would come into town to sell pots and pans, everyone would come out to see what was going on. That was such a big deal. Or when the circus would come to town. When Villaflores was still Villaflores, it was just like Macondo. We had no electricity; there was a generator that was turned on at eight at night and turned off a few hours later. And that was that. There was no television, of course. In Chiapas, television didn’t arrive until 1968, and that was because the government finally ordered that television signals go out as far as Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the state capital, because of the Olympics. But we still didn’t have television in Villaflores until 1970. A few years after that we left Chiapas and moved to Mexico City. It was right there in Coyoacán, where I went to high school, that I read One Hundred Years of Solitude for the first time. So, you can see what that book meant to me.

And then he turns to me, smiling, and says, “Of course, señorita.” He asks my name, and writes the dedication: “Para Hada, como las Hadas, con amor, Gabo.” He wrote my name with an “H,” which, by the way, is how it’s spelled on my birth certificate. (This is a long story and it sounds better in Spanish, but the main thing you need to know is that “hada” means fairy, as in fairy tales, and that’s the way my name used to be spelled–Hada with an “H.” When I was in school, someone wrote “Ada” in an official record a long time ago, and that’s the way I’ve spelled it ever since. But when my daughter was born, I called her “Hadita” with an “H,” because her birth was so magical to me.)

Well, anyway, he signs my book and then Charo runs up to him with her book, and also asks for an autograph. At first he says no, then she points to me, and says, “I’m with her.” So, he asks her name and she says, “Charo. Rosario. María del Rosario.”

“Hmmm,” he says. “María del Rosario de los Angeles…” de who knows what. “What a nice name for a novel.” Of course, by now, everyone in the store sees what’s going on and they start to crowd around him with books, asking for his autograph. “Forgive me,” he says, “But I’m not here to sign books. Just for them, because they’re very special to me.”

Well, you can just imagine–I thought I would die. And then he finishes paying the cashier and they leave. García Márquez y el señor Alvaro Mutis.

So, that’s it. That’s my García Márquez story.

Ada Pereyra Martínez was born in Villaflores, Chiapas. She received her M.D. and Ph.D. from Mexico’s National Autonomous University, and works as a physician and medical researcher in Mexico City.