The Sporting Lie

In February, for the first time in years, Lance Armstrong admitted a kind of defeat.

The legendary cyclist, who returned to the Tour de France this summer after a three-year retirement, scrapped much-ballyhooed plans to run his own blood-doping tests, an unprecedented program designed to show that he is competing without performance-enhancing drugs. News reports quoted Armstrong’s partners, including anti-doping expert Don Caitlin, saying the cyclist’s bid for total transparency turned out to be too expensive and too complicated to enact, especially alongside cycling’s official doping controls, and that it might create a target for hackers to sabotage Armstrong’s reputation.

Pending the race’s outcome in late July, chances are slim that this semi-setback will amount to even a marginal black mark on Armstrong’s estimable legacy. Still, considering how regularly Armstrong points out that he’s one of the most drug-tested athletes on earth, there’s something disconcerting about the notion that he would even try to prove his innocence by piling on more protocols. Dogged by persistent doping rumors—which will surely come up again—you’d think he could have just stuck to his marathons and his new baby and left the Yellow Jersey Circus behind for good. Let them speculate.

Armstrong has never failed a drug test, but there is roundabout logic in his pursuit of an innocent verdict. The 2008 Tour’s third-place finisher, 27-year-old Austrian Bernhard Kohl, who was himself busted for doping, told reporters the top 10 finishers in last year’s Tour could be dirty.

It’s worth reiterating that Armstrong did not race last year. His fans will also be quick to point out that the cancer survivor has been using his comeback as a platform to advocate allocation of more resources to cancer research. All those good intentions come through clearly in John Wilcockson’s new biography, Lance: The Making of the World’s Greatest Champion.

Although the book was apparently undertaken as an independent biography, once Armstrong decided to compete again in France the veteran cycling journalist was given broad access to the athlete’s inner circle of trainers, teammates and family. Working with Armstrong’s people, Wilcockson is able to offer the inside dope (pun intended) on the champ’s training techniques, his rise through the ranks and his triumph over family strife and cancer to emerge as one of the planet’s best-known athletes.

It’s a trajectory that offers few surprises, but Wilcockson certainly knows the business of bike racing, and he delivers a fine primer for anyone who somehow missed Armstrong’s decade-long saga, or maybe forgot about it during his recent hiatus. What’s missing, though, is any in-depth exploration of cycling’s ongoing drug problem. Opportunities to explore the downfall of Armstrong teammates Tyler Hamilton and Floyd Landis, who suffered the ignominy of incriminating test results, are passed over without a second glance. Cycling may or may not be dirtier than other sports, but there is no question that many Tour riders are cheating. Cycling’s Hall of Shame is full.

Journalists who confront the question of sports doping often play a sort of mental parlor game that turns on the question: What if you could take a pill that made you a better writer? What if that pill guaranteed professional prizes and a six-figure book contract? Would you take that pill? And would you publicize the fact? (I’m pretty sure the reader can guess the answer).

In this celebrity age, access is a form of “performance-enhancer” for professional writers. It can help boost book sales and provide shelter when it comes to the sometimes-litigious strategies stars resort to when they don’t like their treatment in the press. If Wilcockson is not cheating precisely, his unquestioning performance under Armstrong’s influence at least runs the risk of leaving readers wanting.

After all, the Armstrong-approved version of this story is already well documented. The cyclist has written two memoirs, his mother has penned a book, and his ex-wife Kristen (whom Armstrong continues to describe as his “best friend”) has contributed her own inspirational story to the pile. It’s a sympathetic portrait in aggregate, and in Wilcockson’s defense, a hard one to resist.

Armstrong grew up not-rich in suburban Dallas with his unhappily married mother, Linda. His birth father was MIA. As a talented runner and cyclist in football-mad North Texas, Armstrong used triathlons and then cycling as a way to set himself apart and prove his worth. As he focused more and more on cycling, he was able to find sponsors, shift his base of operations to Austin, then California, and enviably found a way to split his time between Europe and Texas. Before he was diagnosed with cancer in 1996, he had a two-year, $2.5 million contract with a top-flight French cycling team, an endorsement deal with Nike and a lakefront mansion in Austin.

Then tragedy struck. This is one part of Wilcockson’s biography that shimmers with a sense of humanity that’s missing elsewhere in the book. As complications from cancer and its treatment emerge, Wilcockson paints the scene as heart-wrenching, then hopeful. “Less than two weeks after the chemo catheter was yanked from his chest,” he writes, “Lance spent Christmas week at his mother’s home in Plano. When he arrived, Linda was taken aback by his appearance. ‘It was just so sad to see him,’ she says, ‘the dark circles under his eyes, white skin, no hair, no eyebrows … and to see that his body was giving out.’ She was equally taken aback by his setting up a wind trainer in his bedroom so he could ride his bike. ‘I went to check on him upstairs, and he was on that wind trainer, just pedaling his heart out dripping with sweat.'”

The rest, as they say, is history. Armstrong would recover. He would vanquish his opponents and win an unprecedented seven Tours. He would date singer Sheryl Crow, party with Matthew McConaughey and continue to score endorsement deals with Nike and Subaru. If you haven’t heard all this before, and believe that Armstrong was able to achieve such an elevated level of success over a bunch of known dopers without any chemical assistance himself, this book is for you.

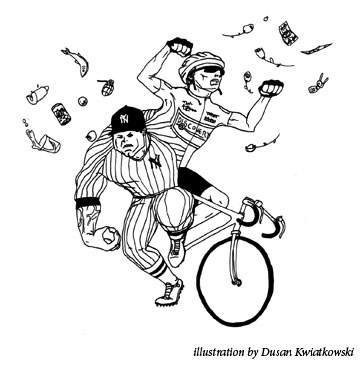

Lance Armstrong may be a clean machine (at least there’s no proof to support a counterclaim), but fellow Texan Roger “the Rocket” Clemens seems likely to go down in history as baseball’s No. 1 cheat. Few have flown higher than Clemens, whose (alleged) self-augmentation may have helped him hold his own in an era of (allegedly) boosted hitters like Sammy Sosa, Mark McGwire and Barry Bonds.

According to biographer Jeff Pearlman, a columnist for SI.com, “The Roger Clemens who exists today is scorned by many as a cheater who used performance-enhancing drugs, broke the law to do so and then lied about it before Congress. He is a man who lives in shame.”

Considering that Pearlman’s book is titled The Rocket that Fell to Earth: Roger Clemens and the Rage for Baseball Immortality, it comes as little surprise that access and empathy aren’t part of the package. But the details of the Rocket’s life are astonishingly similar to those of his cycling counterpart. Without a father figure on the scene, Clemens’ mother took chief responsibility for raising the boy, who arrived in the Houston suburbs for high school with little beyond his as-yet-undeveloped arm and the notion that professional athletics might pave a path to a better life. It emerges that young Clemens was every bit Armstrong’s equal as a master of self-invention.

According to their coaches and trainers, the two outworked teammates and opponents in their pursuit of athletic immortality. Clemens’ legendary workouts left his teammates astonished and ashamed. And though Clemens was an Ohio native, he adopted the same brash Texas attitudes that made Armstrong anathema to the French and George W. Bush anathema to the world. Just as Armstrong worked to break out of the shadow of Texas football, Clemens had to suffer his status as a baseball player in Toronto, where hockey comes first. Armstrong distinguished himself by earning the respect of the French, but Clemens never quite won the hearts of Red Sox Nation, which still spits at the mention of his name. Clemens even dated a chart-topping Nashville singer, Mindy McCready, though he was married to someone else at the time.

For all their similarities, once Roger Clemens arrived as a premier pitcher in the big leagues, he cut a much different figure than Armstrong. For one thing, prior to joining the New York Yankees, Clemens had a habit of melting down under pressure. For another, according to the sportswriters who covered him, he rarely if ever showed the candor or charisma that distinguishes marquee athletes from the merely talented.

So when it turned out that Clemens had apparently lied about using steroids—despite vigorous protestations of innocence, he was one of the many Major League Baseball figures fingered by the congressional Mitchell Report as a steroid user—the public sense of disillusionment was profoundly muted.

“Looking back it is unfortunate how easily the fable was lapped up by the mainstream media,” Pearlman writes. “If Roger Clemens said he worked hard, Roger Clemens worked hard. If Roger Clemens said he ate bumblebee stew for breakfast, Roger Clemens ate bumblebee stew for breakfast. For the nation’s sportswriters, primarily white males in their late 30s and early 40s, Clemens’ success mirrored what they desired in their own lives. You can continue to perform at a high level! You can continue to beat the odds! They wanted to believe in Roger Clemens, because it said as much about them as it did about him.

“So what if his achievements were physically impossible” without drugs?

If Wilcockson can be faulted for his hero-worshipping ways, Pearlman spends so much time building the case against Clemens that he sometimes gives short shrift to what the pitcher actually accomplished in his 24 pro seasons. Even before he was allegedly introduced to the needle by confessed steroid user José Canseco, Clemens had set the MLB record with 20 strikeouts in a single game, picked up three Cy Young Awards (he would eventually win a total of seven), and in 1986 became the first American League pitcher since Vida Blue in 1971 to win the league MVP award. At an age when most fastball throwers tend to tail off, Clemens was posting career numbers. Indeed, he appeared to grow stronger and more athletically dominant after his 35th birthday, helping the Yankees win two World Series after 1996, and cashing ever-fatter paychecks along the way. This unlikely development, in conjunction with Clemens’ general lack of social skills and his willingness to play for the highest bidder, endeared him to few.

Clemens didn’t create the steroid era, though through his actions and attitude may end up defining it. Before stepping over the line, Clemens basically drew the blueprint for guys like Armstrong, combining a relentless pursuit of perfection with a steely stare and a Texas twang. In that light, one wishes Pearlman had placed more weight on the revelation that, by the author’s count, at least 40 percent of all MLB players are likely doping just to stay competitive. “We were just emerging from the mid-1990s, when ‘steroids’ and ‘performance-enhancing drugs’ were words and phrases reserved for the [National Football League], the [World Wrestling Federation] and back-alley gyms and crooked needles,” Pearlman recalls of Clemens’ heyday, before the aging pitcher joined juiced athletes like Jason Giambi in the doghouse.

Clemens didn’t create the steroid era, though through his actions and attitude may end up defining it. Before stepping over the line, Clemens basically drew the blueprint for guys like Armstrong, combining a relentless pursuit of perfection with a steely stare and a Texas twang. In that light, one wishes Pearlman had placed more weight on the revelation that, by the author’s count, at least 40 percent of all MLB players are likely doping just to stay competitive. “We were just emerging from the mid-1990s, when ‘steroids’ and ‘performance-enhancing drugs’ were words and phrases reserved for the [National Football League], the [World Wrestling Federation] and back-alley gyms and crooked needles,” Pearlman recalls of Clemens’ heyday, before the aging pitcher joined juiced athletes like Jason Giambi in the doghouse.

We watch sports to catch flashes of greatness. Such flashes put armchair athletes, weekend warriors and even the occasional non-fan in touch with a world where humans act superhumanly, jumping higher, running faster and throwing farther than the rest of us can conceive. Fans don’t tune in to see meltdowns like Clemens throwing a broken baseball bat at an opposing player, which is what happened in the 2000 World Series. Such falls from grace court comeuppance from guys like Pearlman, who’s done an admirable job of delivering.

Once upon a time, Clemens could claim that he had never failed a drug test. Now, we pretty much know that’s a lie. The jury on Armstrong, as he seems to understand, is still out. Cynics continue to doubt that anybody could compete at such a high level for so long without unfair assistance, and Wilcockson’s awe of his subject doesn’t allow him to close the case. For many reasons, including the pain of his disease and the poetry of his success, an overwhelming number of sports fans still hold out hope that Armstrong is telling the truth. Superficially, at least, he’s created a more appealing persona than Clemens ever could. In that sense, at least, each has gotten the treatment he deserves.

But even if Armstrong turns out to have a secret closet full of syringes, most cycling fans will continue watching the races, just as most baseball fans continue to root for the home team. Cheating has been around as long as sport, and so long as the one getting away with it is our guy, or plays for our team, or would probably win anyway, we’ll continue to tune in, hoping to see just one more flash.

Freelance writer Dan Oko, an avid amateur cyclist, has written for Men’s Journal, Outside and Salon.com. He lives in Austin.