Above: Minh Dang repairs nets on the Johnny II shrimp boat in Galveston, Texas.

Coastal roads in Texas tend to be flat except on the bridges that rise to cross many marshes, bayous, and rivers whose waters meander to Gulf of Mexico ports with long traditions of shrimping. About 95 percent of Texas’ shrimp fleet calls these harbors home: Port Arthur and Sabine; Galveston and Bolivar; Palacios; and Port Isabel and Brownsville.

At the docks in Galveston, shrimp boats’ names reflect their owners’ hope, family, and pride. The Lucky Star promises productive trawling. The Lady Bre expresses the love of Captain Adrian Etie for his wife, Briana. The Capt. Johnny and the Capt. Johnny II and III honor owner Johnny Huyn.

It’s easy to read these boats’ names because many sat idle in their berths even during the height of the shrimping season, which began July 16 and ends on November 30. In normal times, these boats would be out in a bay for the day or at sea for weeks, following shrimp from Texas to Florida and back again. But these are not normal times. The American shrimping industry, from the Gulf of Mexico around Florida to the South Atlantic, is nearly at a standstill, undersold and sidelined by a deluge of cheap imported farm-raised shrimp from Asia and South America that have been “dumped”—sold to the United States at below-market value.

Many owners are keeping their boats docked rather than spending money on diesel, boat repairs, and crew wages to net shrimp that will sell at a loss. The Eties have been running up credit card debt and selling shrimp meant for human consumption for bait because prices are so low. “[Shrimpers] need supplies like ice and diesel. It takes money to get the boat out there,” said Briana Etie. “And if you don’t have a place to sell your shrimp when you get back in, what’s the point?”

If you don’t have a place to sell your shrimp when you get back in, what’s the point?

Minh Dang, a crew member on the Capt. Johnny II, emigrated from Vietnam fifteen years ago and worked steadily in the shrimp industry until this year. With his income based on a percentage of shrimp sold, fewer trips to sea have taken a toll on his family. “I’ve had to borrow money from friends to pay my mortgage,” he said. “And my wife, who’s never worked before, has had to get a job.”

For the first time in the shrimp industry’s century-old history, governments of five of Texas’ coastal counties—Galveston, Matagorda, Calhoun, Chambers, and Jefferson–have issued shrimp disaster declarations or resolutions, publicly pleading for help. Counties and parishes in the seven other southern shrimping states have also declared shrimp disasters.

The Florida-based Southern Shrimp Alliance, the industry’s primary lobbying organization, has requested help from southern governors and members of Congress. “The U.S. shrimp fishery throughout the Gulf of Mexico and Southeast region is suffering an unprecedented catastrophic crisis that threatens its very existence and the many small family-owned businesses that are at the core of the economies of coastal communities throughout the region.”

This year’s crisis arose from a longer slump. Nationwide, shrimp consumption is booming, but Americans no longer eat as many Gulf shrimp.

In 1985, Americans ate 2 pounds of shrimp per person and 90 percent of that shrimp was caught in the United States. By 2021, Americans were consuming nearly three times as many shrimp—an average of 5.9 pounds per person per year, according to the National Fisheries Institute. But 94 percent of that shrimp is imported.

In 2022, the United States imported more shrimp than Americans eat. Both imported and domestic shrimp have piled up in freezers at shrimp processors. “They literally have nowhere to store it or sell it. Cold storage is full across the Gulf. I’ve heard that there are freezer trucks in some parking lots in cold storage facilities in Florida,” said Laura Picariello, a marine fisheries expert with Texas A&M University’s Sea Grant in Galveston. “[Shrimpers] are really struggling. There are people who absolutely are not going to be in this business by the end of the year if things don’t change, and I don’t know how things are going to change at this point.”

Prices have plummeted. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s latest data (from May) showed shrimp prices for three sizes of shrimp were at their lowest since 2002, and since then, they’ve plunged more.

The Texas shrimp fishery remains the state’s largest commercial fishery, accounting for over 80 percent of commercial fish landings. In an average year, Texas shrimpers and shrimp processors contribute about $320 million to the Texas economy and employ over 5,000 full- and part-time workers, according to Texas A&M.

About a third of Texas shrimpers are of Vietnamese heritage, a third are Caucasian, and a third are Hispanic. The Vietnamese fleet is located primarily on Texas’ north coast and the Hispanic fleet is on the south coast. Palacios is the port where all these cultures meet. “Palacios is a really great mix of all three, and they all work really well together,” Picariello said. “It’s a really cool place.”

But this year, shrimpers in Palacios and elsewhere are asking Picariello how to apply for food stamps. And in Port Arthur, Father Sinclair Oubre, a Catholic diocesan priest and the treasurer of the Port Arthur Area Shrimpers Association, is worried about shrimpers’ mental health and their risk of suicide.

Shrimpers blame the federal government for the current shrimp crisis. “I just don’t understand why the government doesn’t want to help control [shrimp imports] and help our own American companies,” said Briana Etie, the Galveston-based shrimper’s wife.

I just don’t understand why the government doesn’t want to help control [shrimp imports] and help our own American companies.

Starting in the 1970s, to fuel the economies of developing countries, international monetary funds like the World Bank—which is partly funded by the U.S. government—supported the construction of aquaculture facilities in Asia and South America. Some of these loans were later forgiven. With those investments, inexpensive labor, and loose environmental restrictions, these countries could produce shrimp cheaply, which they exported to the United States starting in the ’80s.

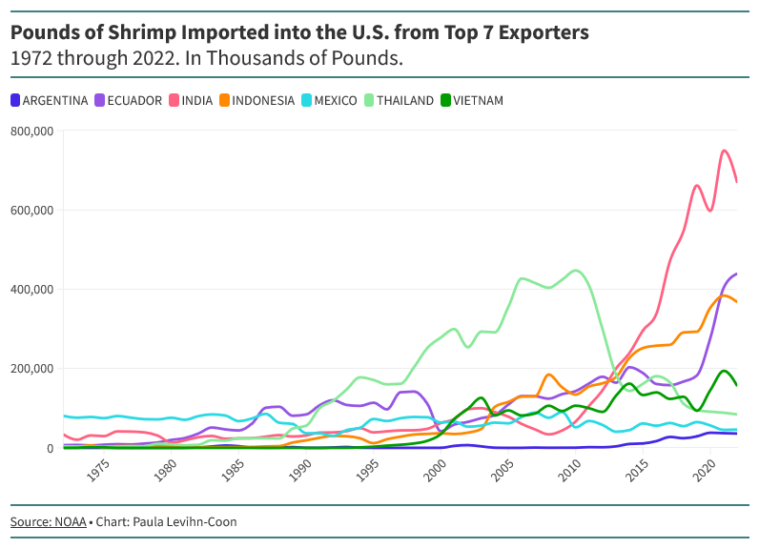

Ecuador and India are currently perceived as the largest threats to the U.S. shrimp industry. In five years, from 2016 through 2022, the volume of shrimp imported from these two countries skyrocketed to 59.8 percent from 37.5 percent of U.S. shrimp imports, according to trade data.

“The World Bank is financing the Ecuadorian shrimp and they’re using our tax dollars to do it. They’re making it tough,” said Luke Rawlings, who owns shrimp boats and a bait camp in Matagorda. When the Texas Observer caught up with him by phone, he was hauling a trailer full of frozen shrimp to New Mexico to sell his catch directly to restaurants.

Ecuador grew its shrimp industry to fulfill demand from China. During the pandemic, however, China stopped importing shrimp from Ecuador. With nowhere to export its shrimp, Ecuador sent it to the United States. China has since resumed its imports, but Ecuador is not stopping exports stateside. Its worldwide exports have grown 15 percent since last year, to 2.34 billion pounds. Ecuador is currently the world’s largest shrimp exporter, according to Intrafish.

Shrimp farms in India are heavily subsidized. For example, in 2017, shrimp farmers in Punjab received a 90 percent subsidy to dig shrimp ponds and a 50 percent subsidy for purchasing equipment and feed.

American shrimpers, in contrast, do not receive financial help from the government. “It’s not like farming. There are no subsidies. There’s no money going to help fishermen,” said Nikki Fitzgerald with Texas A&M’s Sea Grant, who advised the Chambers and Jefferson County judges who decided that their disaster declarations were necessary.

Besides the financial harm caused to American shrimpers, there are environmental and ethical concerns about importing farm-raised shrimp. These include the use of forced labor in shrimp aquaculture and processing; deforestation of coastal mangrove swamps—which are nurseries for aquatic animals and protect coastal lands from erosion—to make aquaculture ponds; and the chemicals and antibiotics found in imported shrimp.

A 2015 Consumer Reports investigation, “How Safe is Your Shrimp?”, found that 61 percent of the shrimp they tested from Ecuador and 74 percent from India contained dangerous bacteria, antibiotics and drug residues. It also noted that the Federal Drug Administration only tests 0.7 percent of imported shrimp.

In contrast, the European Union, Canada, and Japan test between 15 and 50 percent of their imported seafood, according to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

In Texas, bay shrimpers usually go out for the day, netting bait shrimp year-round and shrimp for human consumption in the fall and spring. They keep their catch on ice or in live wells.

Many Gulf shrimpers go to sea for weeks at a time, only returning to port to refuel or make repairs. Shrimp are individually quick-frozen and sorted by size at sea. For the last two years, however, shrimpers have not traveled long distances because boat owners can’t afford the diesel this entails. “This has been a very big disruption Gulf-wide in how this fleet operates,” Picariello said.

When the season ends, boat owners conduct routine maintenance on their boats, but these days “there’s a lot of these people don’t want to put any more into their boats,” said Nga Pham, a dock owner who has been in the shrimp industry her whole life. Many shrimpers have canceled their insurance policies, she said, a risk at any time but especially during hurricane season.

There is little hope of improving this situation quickly enough to rescue Texas shrimpers this shrimp season, although there is some movement on the issue. On September 28, U.S. Senator Bill Cassidy, R-L.A., introduced the India Shrimp Tariff Act, which would raise tariffs on shrimp from India up to 40 percent by 2024. On October 25, a coalition of shrimp organizations petitioned the U.S. International Trade Commission to impose tariffs on shrimp from Vietnam, Ecuador, India, and Indonesia.

Deborah Long, with the Southern Shrimp Alliance, said other efforts to get the United States Department of Agriculture to buy American shrimp for government entities like prisons and military bases; increased testing of imported shrimp; implementing bans on countries that use slave labor; and new tariffs could help the industry fairly quickly, but international trade negotiations take much longer to show results.

“When you look environmentally, when you look health-wise, when you look at national security and the general food supply, having a domestic [shrimp] industry is vital,” Long said. ‘“But more importantly, [shrimping] is a huge economic driver in coastal communities. They are not just the boat and the crew. They are the icehouse and the dock and the trucks that are moving the shrimp. There are entire communities that are at risk if this industry goes under.”

Some boat owners continue sending their vessels to sea, taking a loss after paying for fuel, crew’s wages, and repairs, just to keep their skilled crew from taking land jobs “because once an owner loses his crew, it’s very difficult to find somebody who is willing and capable to go out to sea for several weeks and run the boat the way it needs to be run,” Long said.

At the Palacios docks, Ken Garcia greets Captain Oscar Narahao and the arriving crew of the Father Mike, the boat named after his father’s cousin, a Catholic priest. While he supervises the off-loading of bags of shrimp from the hold onto pallets, he reflects on this shrimp season. “It’s been pretty tough, pretty bad. A lot of imports,” he said. “Our own government let us down.”

Garcia’s grandfather, Edward Garcia Sr., started his family’s shrimp business in 1952. Garcia and his father now own 15 shrimp boats, one of the largest shrimp fleets in Texas. Despite low shrimp prices, they have sent their boats to sea for 50 days at a time this season, but for fewer trips than usual.

“It wasn’t profitable for us to work, and there’s only so much bleeding we can do,” Garcia said. “I had a lot of families to worry about, people counting on me, so we had to try. Most of my workers have been working with me for the last 15 years, and a lot of them worked for my dad for the 15 years prior to that. So, you know, I owe it to them.” He credits H-E-B, his largest customer, with his ability to send boats to sea because “they bought a lot of shrimp in this weak market.”

He plans to tie up his fleet at season’s end and does not know if or when he will send boats back out to sea. Five years ago, his captains, who are paid 35 percent of the value of the shrimp they catch, made $80,000 to $100,000 a year, and his crews made about 80 percent of the captain’s wages. “This year, they all made about half of that,” Garcia said. “They’re working twice as hard for the same money.”

The Observer asked Garcia if he would like his only child—a 1-year-old son—to go into the shrimping business one day. “I don’t know. I was lucky enough that I got to do what my dad and grandpa did but maybe three generations is enough,” he said. “Maybe he should do something else.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story mistakenly identified Nikki Fitzgerald as a signatory on the Chambers County shrimp disaster declaration. The Observer apologizes for the error.