In Fort Worth, No Butts About It

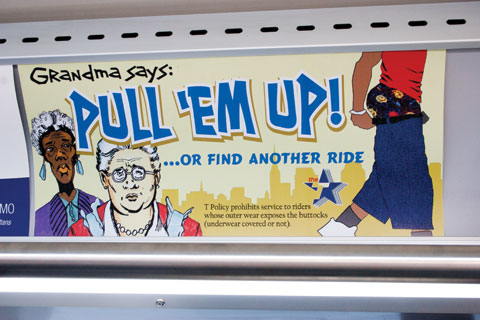

In Fort Worth, when the bus pulls up, young men pull up their pants. If not, granny or a bus driver will get them. On most buses, a poster featuring two stern-looking grandmothers—one black, one white—reminds riders of the transit agency’s policy: “Grandma Says Pull ’Em Up … or Find Another Ride.”

In May, the Forth Worth Transportation Authority, known as the T, became the first transit agency in the state—and possibly the nation—to ban sagging: wearing pants that droop below the waist, exposing underwear. Bus drivers and supervisors police morals and fashion, telling potential paying customers to pull up their pants or get off the bus.

According to T spokeswoman Joan Hunter, one or two people are removed from the bus every three to four days, down from two or three per day during the first few weeks of the policy, and 50 the first day. That’s out of a weekday average of 23,000 passenger trips. Violators are removed from the bus, and those who won’t go without a fuss can be prevented from riding the bus for 30 days. (There are no criminal charges or fines for sagging.) The policy is part of a dress code that also requires riders to wear shirts and shoes. T officials say the saggy pants rule shows respect for other passengers.

From the beginning, Hunter said, the idea—inspired by an anti-sagging campaign led by District 5 City Council Member Frank Moss, an African-American—received overwhelming support from the community and bus riders. Six months later, no one has challenged a policy that Hunter describes as a “non-issue.” And in quarters where one might expect opposition—the African-American community, where youth culture is closely associated with sagging—there’s strong support for the policy.

In the 20 years since sagging appeared on the urban runway, older African-Americans have called the fashion “ugly,” “stupid” and “disrespectful,” and have often been the driving force behind laws and policies prohibiting the practice from Florida and New York to Georgia and Illinois. The fashion has its roots in prison, where inmates are prevented from wearing belts for safety reasons. But even as the style has moved from the margins to the center of American youth culture, to Moss and his supporters sagging still symbolizes the prison pipeline that runs through many black communities. It’s irrelevant that Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong was bumped from an airplane for sagging, or the ’tween heartthrob Justin Bieber sags in nearly all his videos.

Black youth labor under a different standard, he said. Supporters of anti-sagging measures say they’re trying to prevent black kids from being profiled by police and other authority figures. But the bans make it easier to marginalize—if not criminalize—black youth. And young people of all races say sagging is simply what they do.

In May, Fort Worth became a front in a culture war that has profound implications for black and brown youth.

Councilman Moss sees the irony in his leadership of the local “Pull ’Em Up” campaign, a citywide effort to get young men to voluntarily pull up their pants. His 28-year-old son, a college graduate, sags when he’s not at work.

Councilman Moss sees the irony in his leadership of the local “Pull ’Em Up” campaign, a citywide effort to get young men to voluntarily pull up their pants. His 28-year-old son, a college graduate, sags when he’s not at work.

“It’s something that drives me and his mother up the wall,” Moss said, adding that his son knows how to dress appropriately for work.

Moss’ campaign inspired the transportation authority’s anti-sagging policy. Moss asked T officials to display the poster featuring the iconic grandmas as a courtesy, but said he was surprised when they banned sagging outright. Since the policy went into effect, he has thought twice about its ramifications and how best to move the city’s anti-sagging campaign forward.

“We have to look at the social impact, and make sure [our approach] does not further marginalize youth,” Moss said.

“I just want to see [young black men] succeed,” he said, when pressed about the value of the campaign, when minority youth face so many other critical issues, from higher-than-average unemployment to low graduation rates.

“Sagging limits their opportunities, ” he said, adding that black youth are more likely to be penalized than other young people for their appearance.

A few years ago, Dallas made national headlines for its campaign to get young people (and some adults, too) to pull up their pants. Signs were posted on billboards throughout the city and rallies encouraged youth to stop sagging. Former Mayor Dwaine Caraway appeared on the “Dr. Phil” show. At one point, the Dallas City Council toyed with creating a sagging ordinance, but dumped the idea for legal reasons. Three years ago, a Florida court ruled an anti-sagging measure in Riviera Beach, Florida, unconstitutional.

Moss’ activities in Fort Worth grew from the Dallas initiative. In 2008, Moss worked with the Fort Worth Independent School District, where his wife is a board member, the city, and Tarrant County to launch the “Pull ’Em Up” campaign. (The Fort Worth school district bans sagging at school.) The T agreed to place the anti-sagging signs on the bus. Based on the positive response from riders and bus drivers, Hunter said, transit administrators decided to create the sagging policy.

During rush hour on a recent weekday, a handful of young men adjusted their pants as a supervisor hovered around the bus bays at the city’s commuter hub at 9th and Jones streets. Most of the people riding the bus were black and Latino. By 5:45 p.m., the flow of commuters had slowed to a trickle.

James Nolan, 18, was talking to friends. His black shorts drooped a few inches, exposing a second pair of shorts. “It’s not fair,” Nolan said, referring to the no-sag policy. “Everybody has their own way of dressing.”

There should be a line between preaching dress-for-success and banning how youth dress, said Derek Wilson, a psychology professor at Prairie View A&M University who specializes in adolescent behavior.

“I can sympathize with the idea that we want our youth to pull up their pants,” he said. “But my greatest concern comes down to being mindful that our policies could be having an adverse effect on [young people].”

Wilson found out about the bus policy at a meeting of the state’s black city council members earlier this year. The meeting was chaired by Moss, who asked Wilson for his thoughts. “I do not support [a policy] that says you cannot get on a bus to ride from Point A to Point B,” Wilson said. “Now you are restricting movement, and some minorities already feel they cannot go across town.”

Not long after the Fort Worth policy went into effect, a University of New Mexico football player was removed from an airplane and arrested because he refused to pull up his pants when a US Airways employee asked him to. That type of treatment has to be guarded against, Wilson said.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has been active in anti-sagging cases across the country, in some instances joined by the NAACP, which has expressed concerns about such policies’ racial-profiling implications.

Terri Burke, executive director of the Texas ACLU, said the organization hasn’t heard from anyone regarding Fort Worth’s bus policy. “It seems to us that this is a free-expression issue,” Burke said. “It hasn’t been tested at any substantial court level where we could fall back on some precedent. But it certainly seems like a violation of the First Amendment.”

Moss’ southeast Fort Worth district includes the Stop Six neighborhood, a historic African-American community that got its name from a stop on a former electric passenger train line. It encompasses well-manicured middle-class communities as well as public housing developments, and Paul Laurence Dunbar High School.

Moss’ southeast Fort Worth district includes the Stop Six neighborhood, a historic African-American community that got its name from a stop on a former electric passenger train line. It encompasses well-manicured middle-class communities as well as public housing developments, and Paul Laurence Dunbar High School.

On a warm October day, when the final bell of the school day rang, students poured out of the doors and “dropped ’em.” Faded jeans, new jeans, belted jeans, creased jeans, all hung low. One boy walked like an old man; his pants, hanging closer to his upper thighs than to his waist, slowed him down.

Several students at Dunbar said they knew about the bus policy. Most don’t like it, but some, like Eric Williams, said they understand that sometimes it’s inappropriate to sag. “It’s a respect issue,” said Williams, 17. And he knows people shouldn’t sag at a job interview.

In the middle of the after-school crowd, Markeisha Hodge, 16, is a standout. Her blue T-shirt matches her jeans, which match her blue-and-white checkered boxers, at least three inches of which are visible. “This is our style,” she said. “I’m not bothering anybody.”

“I pull up my pants when I walk past my elders.”

A recent commentary on the website theGrio asks, “Why won’t the ‘sagging’ fad fade away?”

Sagging was once the domain of hip-hop culture; today, hip-hop fans and people who sag are as racially diverse as a Benetton ad. Yet sagging is still associated with black youth culture, and with a form of rap music whose heroes have done time. In a sense, the attack on sagging is a continuation of critiques of gangster rap in the 1990s and its attack on middle-class values.

Johnny Muhammad, president of UMOJA, a mentoring program for boys that operates in 14 Forth Worth schools, said sagging is a symptom of bigger issues. “It’s a mindset and a set of values,” he said, citing a young man who lost his job because he refused to pull up his pants.

“In our community (black and Latino), it’s a rite of passage to be incarcerated. This is a new day; it’s not like our generation,” Muhammad said.

Such sentiments have fueled momentum for anti-sagging ordinances and policies among African-Americans. Recently, residents of Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood, a low-income black community, asked the City Council to amend the city’s indecent exposure law to include sagging. In suburban Chicago communities such as Lynwood and Sauk Village, youth can be ticketed up to $250 for sagging.

In yet another approach to stopping sagging, two black lawmakers in the state pushed through a law that bans sagging on public school grounds. Violators face fines, suspension, and other disciplinary measures that can lead to involvement with the juvenile justice system, and eventually prison.

At the end of the last school year, Moss and Muhammad met with hundreds of boys to prepare them for the new bus policy and the long summer ahead. Most of them took the news well, Muhammad said.

While he supports the policy, he said bus drivers don’t have the training to communicate the policy appropriately. That could lead to trouble on the bus, he said, “A lot of parolees are getting on the bus to go see their parole officer,” he said, ticking off heavily used routes such as “the 4,” which goes up and down East Rosedale Street in the heart of the Stop Six neighborhood. “They are already in a bad mood.”

Muhammad tells young people that sagging is associated with gang- bangers, which means they’ll be profiled by police officers. “We take the holistic approach: Don’t give them a stick to beat you with,” he said.

Yet he said he would oppose a city ordinance against sagging. “We know little brothers can’t afford to be ticketed,” he said. “And we don’t want them to be ticketed.”

UMOJA got involved in anti-sagging initiatives after older women in the community complained about seeing young men’s underwear. Muhammad said rap stars like Lil Wayne are heroes to young people. But Muhammad acknowledged that the rapper’s appearance—he sags and has lots of tattoos—wouldn’t be accepted in most workplaces.

“Would you hire Lil Wayne if he came looking for a job?” he asked.

Moss said the majority of young people who sag are good kids. But he insists that appearance shapes the perceptions of school officials, police, and employers. A video produced for the “Pull ’Em Up” campaign features a chorus of adults explaining just that. In one segment, a coordinator at a local day-labor agency recalled a job fair at Six Flags where kids with saggy pants were passed up for summer jobs. In another, an adult attempts to connect sagging with poor academic performance—a position that is unsubstantiated.

In a final support of his efforts, Moss tells this story: “[Dallas Councilman Caraway] saw this image on the street in Dallas. It’s a prime example involving a family with three kids. The wife was pushing a child in a carriage. The father had one child by his hand, holding his pants up with his other hand. And the other child was walking unattended.”

“They don’t care,” Moss said. “They have no pride. And they also are limiting their opportunities.”

Sagging may offend some in the community, but does telling young people of color to pull up their pants really stop them from being marginalized?