Caldwell Czechs In

A version of this story ran in the January 2012 issue.

There were four of us sitting around a table at the Longhorn Bar and Grill in downtown Caldwell, just across the street from the Burleson County courthouse. My companions were all retired, and they had nothing better to do. Charles Barack and Joe Rychlik were talking about Czech.

“My parents never spoke it,” Charles said. “Never learned. Grandpa wouldn’t teach them. He wanted them to learn English.”

He gestured with his Shiner and leaned over the table. “In fact,” he said, “once I started to pick up a little, he got mad. He said, ‘That’s not for you to learn.’ He said I was an American now, and that we were going to leave all that behind.”

“Oh, my parents always talked to us in Czech,” Joe said. “So did all their friends. I learned pretty quick that if I asked my friend’s mother for a kolac in Czech, I’d get it a lot quicker than if I’d asked in English.”

Junior Barone laughed. “Ask in English, you might not get anything at all.”

Joe turned to me. “Back then, it was very common. You’d do business at the Czech stores in Czech; you’d talk Czech in school with your friends,” he said. “When I worked at the post office, sometimes customers would come in and we’d do their business in Czech. Now, not so much.”

Charles nodded. “Yeah, no one much speaks it anymore,” he added. He looked at his beer. “Start to think sometimes that something’s been lost there.”

At this, he turned to Joe. At 66, Joe describes himself as the town’s youngest Czech speaker. When I arrived in Caldwell to report a story on Czechoslovakian Texas, I began by calling local authorities including the Chamber of Commerce and the Burleson County Tribune. I would ask them questions about the Czech settlement in Texas, they would listen, and then they would say, “Have you talked to Joe Rychlik?”

Joe’s family history is in many ways the story of Czechs in Texas. It’s also a window on an almost-forgotten part of the American immigrant narrative. In a state where “immigrant” has come to be synonymous with “Mexican,” it’s easy to forget how many Europeans left home for new lives in Texas.

I met Joe Rychlik at his house in Caldwell, a red-brick structure on a side street a few minutes from the town square. The bricks are subtly different shades of red. Joe collects antique bricks; those on the walls of the house are from a half dozen long-shuttered brick factories.

I met Joe Rychlik at his house in Caldwell, a red-brick structure on a side street a few minutes from the town square. The bricks are subtly different shades of red. Joe collects antique bricks; those on the walls of the house are from a half dozen long-shuttered brick factories.

He is a big man, tall and broad across the chest, with an ample belly and a loud laugh. With his shock of white hair he resembles a beardless Santa Claus. The inside of the house was snug and eccentrically decorated with antique appliances and heirloom plate collections. Antique revolvers sat under glass on the coffee table. A plaque by the kitchen read, “I only drink wine when I’m alone or with people.” Joe saw me looking at it.

“That’s a gift from a neighbor,” he said. “Me, I prefer beer, or…” he rooted around in the kitchen, emerging with a glass bottle lettered in Czech: “slivovice.”

He pointed out the back window, toward the rolling prairie. Cattle grazed in the yard next to his. “If you look back there, way back, you can see the farm where I grew up.”

The farm was a beige smudge among other beige smudges. “Here,” Joe said, “let’s go take a look.” We got into his Chevy Tahoe and set off. In a few minutes we were out of town, passing farmland portioned off with barbed wire. We passed a white clapboard church with a sign out front advertising services for the Moravian Brethren, a Czech Protestant church organized a century before Martin Luther started what became the Reformation.

Finally Joe drove us through a break in the barbed wire to a little wooden house—made of planks—that looked like a holdover from an earlier time. A little pear tree grew out front.

“This is where my family has lived since my great-grandfather,” he said, pointing around. “He came, bought the land, and Rychliks have lived here since.”

Joe’s great-grandfather—also named Joe Rychlik, but we’ll call him Grandpa Rychlik—grew up in Moravia, in the southeast of what is now the Czech Republic. He was a farmer, working a small plot that provided just enough to feed his family. There wasn’t enough land to grow surplus crops for sale, so there was little money. As Rychlik lore has it, at the age of 60 he decided “to take the Rychliks we like to America, and to hell with the rest,” Joe said.

Grandpa Rychlik’s decision to leave his homeland for an unknown foreign country reflects how bad things were in Central Europe a hundred years ago, and reminds Americans of the unbridled possibilities people associated with America. The Czechs had no country of their own; their homelands of Silesia, Bohemia and Moravia were provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Young men were drafted into the imperial military and sent to die in far-off territorial wars. A small, entrenched, largely foreign aristocracy controlled most of the available farmland.

As early as the 1850s, Czechs began to leave for America. Some were political radicals, disillusioned by the failures of the great liberal revolts that swept Europe in 1848. Some were simply looking for a bit more land. Whatever their reasons for going, in the decades that followed, in taverns across the Czech lands, people crowded around and read aloud the letters those first emigrants sent back. The letters described a world undreamed of. A place where a man could be what he wanted. Where if he worked hard enough, he could own land.

“I’ve read through hundreds of letters that Czechs sent home from Texas,” said Clinton Machann, a historian at Texas A&M University and Caldwell High School graduate who specializes in Czech Texas. “You read them today, and there’s this remarkable shine of optimism that comes through them. Despite the hardships of the new country, despite whatever discrimination they dealt with, there’s this feeling of being liberated, of being in a place where anything was possible.”

Grandpa Rychlik’s brother left Moravia in 1880; his letters home were enough to convince Grandpa Rychlik to follow him. In 1882, his young family caught a ship to Galveston, arriving at the crest of a wave of Czech immigration to the United States. By then there were already many Czechs in Caldwell and the surrounding communities of Central Texas. By 1900 there would be 9,204, and by 1910 there were 15,074, mostly clustered in a few small enclaves like Caldwell.

Many were eager to bring more of their countrymen to the area. One wealthy Czech landowner loaned Grandpa Rychlik money at almost no interest to buy a farm—provided he and his family stayed in New Tabor, just outside of Caldwell. Grandpa Rychlik fell out with his brother for reasons no one remembers anymore. For the first time in the family’s memory, Rychliks worked and raised crops on land of their own.

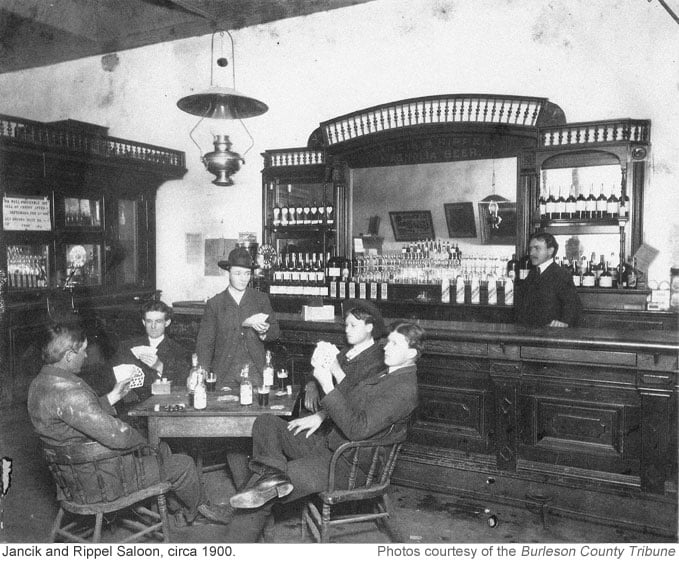

The Czechs of Central Texas were unlike other Czech colonies in the United States. They were from the opposite side of the Czech lands—Moravians instead of Bohemians. Elsewhere Czech immigrants were mostly “freethinkers,” shunning the authority of a church; in Texas they stayed religious. (Most were Catholic, but a substantial minority were members of the Protestant Moravian Brethren.) In towns from Caldwell to West to Shiner, they built Czech-speaking schools and churches and breweries. Often they settled near Germans and Poles, with whom they shared tastes in food, music, and politics.

The Czechs of Central Texas were unlike other Czech colonies in the United States. They were from the opposite side of the Czech lands—Moravians instead of Bohemians. Elsewhere Czech immigrants were mostly “freethinkers,” shunning the authority of a church; in Texas they stayed religious. (Most were Catholic, but a substantial minority were members of the Protestant Moravian Brethren.) In towns from Caldwell to West to Shiner, they built Czech-speaking schools and churches and breweries. Often they settled near Germans and Poles, with whom they shared tastes in food, music, and politics.

Machann, the historian, says that most Texas Czechs worked hard to integrate into American society.

“They saw America as a new homeland,” he said. “They generally had a very positive point of view about their new homeland—they wanted to fit in. Remember, the Czechs at that time didn’t have a country. They had fewer ties to Europe than other groups—their ties were to the Czech people and culture, not the Czech land. And the people could go to America.”

From the beginning, Czech-Texas culture was marked by a high degree of participation in American society, and at the same time a certain insularity and self-reliance. They learned English. They ran for local office. But they also established cultural institutions of their own. They published Czech newspapers such as Nasinec, a weekly started in 1913, which today is probably the last Czech-language newspaper in the country. They formed mutual-aid societies to provide community insurance to farm families. Over time, these societies evolved into social clubs that sponsor barbecues and polkas.

It was not quite an idyllic world. The arrival of thousands of non-English-speaking foreigners created tensions among the already established population, primarily Scots-Irish Protestants. The new immigrants’ Catholicism didn’t help. The KKK campaigned against Czechs, Protestant and Catholic alike.

But given what the Czechs had experienced in the Old Country, Machann says, Texas was nothing. “There weren’t many people in Texas who would have refused to sell a Czech land if he had the money,” he said. “In Moravia, that wouldn’t have been true.”

The Czechs held so tightly to their culture that Joe and his brother Bernard grew up in the 1960s—80 years after the heyday of migration—in a community that was in many ways a time capsule of 1880s-era Moravia. Like many immigrants, Caldwell’s Czechs were more loyal to their traditions than those who had stayed behind. The boys were raised on folk songs that had long since died out in the Old Country. They learned to speak Czech—in the distinctive accent of their homeland—even as they learned English. Even now, Joe, whose grandfather was born in Texas, speaks English with an identifiably Czech accent. His vowels are a little squashed; his “ th” sounds more like a “d.”

I asked him about this as we were walking back to his car. In the ’90s, he told me, he was touring the Czech Republic with his wife. He said something in Czech to a local woman. She heard his accent and said, “Oh, you’re from Vizovice,” a nearby town.

“I told her, no. My great-grandfather was,” Joe said, shaking his head in wonder as he recalled the incident. “The accent was still the same.”

Driving back toward town, I asked Joe what the hardest part of growing up Czech in Anglo Texas was. Was there much discrimination?

“No,” he said. “We were still white, remember. We went to white schools when the schools were segregated. And there were so many Czechs in Caldwell. . .”

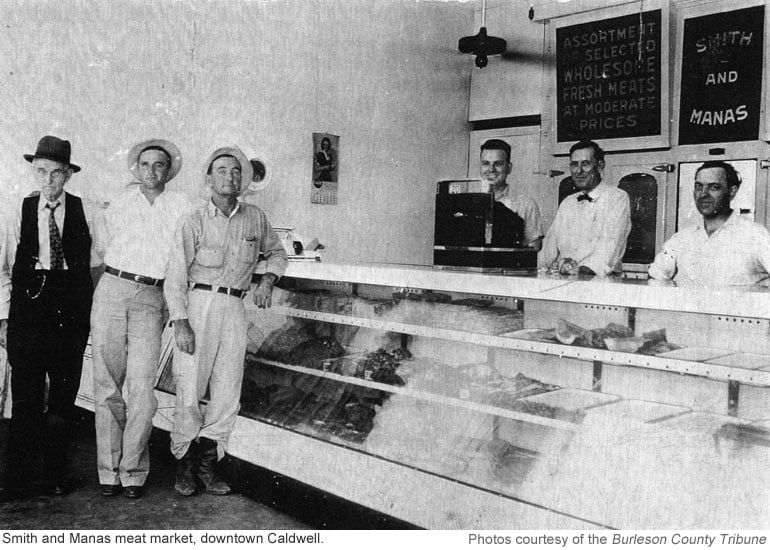

But sometimes they still felt like outsiders because of religion. One of his most vivid memories, he told me, is of sitting in the stands for a Friday night football game in the days before Vatican II, smelling the hot dogs cooking. The hot dogs were from the Manas Meat Market, a Czech-owned deli whose legendary sausages attracted people from all over the county. It’s a clichéd rural Texas image: Friday night football and hot dogs.

“But I was Catholic,” he said. “And back then we still couldn’t eat meat on Fridays. So week after week, I would see my Protestant friends eating those hot dogs, and I would just be so jealous.”

Years later, Joe said, a high-school friend called him. “He said, ‘you know we can eat meat on Fridays now.’”

“I said, ‘Yeah, of course.’ And he said, ‘You know what I want to do?’”

Joe did. Manas Meat Market had closed by then. There was no football that week. But that Friday night, the two went to the stands, sat in the dark, and stuffed themselves with sausages.

We were pulling back into town. On Joe’s car stereo, Czech-American Joe Patek was singing a polka tune called “In Heaven There Is No Beer” to bouncing accordions.

We were pulling back into town. On Joe’s car stereo, Czech-American Joe Patek was singing a polka tune called “In Heaven There Is No Beer” to bouncing accordions.

Joe’s wife Donna was waiting for us inside the house. She grew up in the Church of Christ, in Eustace, in East Texas. She took a job as the county extension agent in Caldwell in 1971. She was 23, fresh out of college. Caldwell stunned her.

“I thought I was in a foreign country,” she said. “I remember my first day at work I went to my office in the basement of the courthouse. And out the window I could see the Dergac lumberyard, and across from that was Vychopen dry goods. And by those was the Siptak-Pargac drug store. We didn’t have names like that in East Texas. I called my mother and I said, ‘Mother, I’m not in Texas anymore.’

“I didn’t know how to act, what was expected of me, how to pronounce any of the names in the phone book.”

She learned. She learned other things, too. Joe, with the aid of “at least a six-pack of Schlitz,” taught her to polka. When Joe asked her to marry him, she said yes. His only condition: She would become a Catholic.

She said yes. I asked Joe if he would have converted for her. He frowned. “I don’t think so,” he said. “I was raised in the Church.”

Much of Donna’s extended family was furious about her decision. Her stepfather’s family was staunchly anti-Catholic. She wasn’t sure her parents were coming to the wedding until she saw them there. No one else from her family came.

“You should have seen their faces,” Joe said. “I mean, you take a big Baptist wedding, a big Church of Christer wedding, it’s 50 people and maybe they have cake and punch. A Czech wedding is 300 people, brisket, beer, dancing.”

“But they went back,” Donna said, “and they told everyone in the family what a good time they’d had, how it was the best wedding they had ever been to. And when we had our 25th anniversary, what do you know? A lot of them came.”

“So in some ways,” I said, “you were an immigrant too.”

She laughed. “It’s good,” she said. “I make a better Czech Catholic than I ever did a Church of Christer.”

Few people in Caldwell speak Czech anymore. Joe ticks off names of people he used to speak with in Czech. Neighbors and friends, long dead. His brother Bernard, killed in a car accident last year.

He shook his head and said sadly, “I’m losing everyone I can talk to.”

We were leaving the bar where we had been drinking beer with his friends. I asked him if it bothered him that the young kids weren’t learning Czech. “It’s sad,” he said, “but that’s the way things go. Nothing ever stays the same. But what’s remarkable is that we still have a strong heritage.”

I could see his point. Part of the dilemma of being an immigrant is deciding how much of your culture to hold on to and how much to trade in for a place in the broader society. Part of the immigrant experience is watching your culture slowly ground away, to be replaced by something else. This has happened to the Czechs, as it has happened to all groups. The Caldwell of today is not the Caldwell of Joe’s youth. It isn’t even the Caldwell that Donna found in the 1970s. The Czech names are gone from the courthouse square. No one does business at the post office in Czech. Joe Rychlik is stuck at the center of an ever tightening circle of people who remember the old language.

The remarkable thing about the Caldwell Czechs is not how much of their culture they’ve lost, but how much they have managed to keep. Caldwell’s Kolache Festival (in Czech, “Kolache” is plural for Kolac), a brainchild of Joe’s brother, among others, has grown over the last 27 years from a small bake-off to a full-blown cultural festival, attracting as many as 20,000 visitors every September.

Most of those who attend aren’t Czech, of course. But many are. And many of those who participate in the festival are children.

“We have lots of kids, teenagers or younger, who enter to show off the traditional Czech dances,” said Louemma Polansky, the Kolache Festival organizer. “We had 35 youth enter the bake-off.”

Which, for a town of 4,000, isn’t bad. Polansky herself isn’t Czech, but like Donna Rychlik she calls herself an “adopted Czech.” She married a Czech and threw herself into the culture.

“We have a lot of youth who are active in the festival, active in 4H,” she said, “but as an adult they don’t forget. One young lady grew up in Caldwell, entered in the baking competitions. Then after she graduated college, she ran for Miss Czech Texas, and when she won it, a whole bunch of us drove up to Nebraska to support her at the nationals.

“Now she comes back—comes to the Kolache Festival and sings the Czech national anthem. Even though she’s grown up, she comes back for that weekend and participates. So she hasn’t forgotten her roots. And there are many people like that. It’s not something you can just walk away from. A lot of people are born and raised in Caldwell, and they end up coming back.”

Or, like Joe Rychlik, they never leave. He and Donna have built a house that is painstakingly decorated, full of paintings and knicknacks that bespeak their life together. It would be almost impossible to move. No one I know has a house like that. No one I know is so settled.

When I asked Joe why he never left Caldwell, he paused, as if the question didn’t quite make sense. “This is where my friends were,” he said. “This is where my family was. Why would I have left?”

Opportunity, I suggested? See the world?

He laughed. “I got a chance to stay in Caldwell,” he said. “That’s where I always wanted to be.”

Contributing editor Saul Elbein lives and freelances in Austin.