Port Arthur Blues

A Native Son Returns to Revitalize His Pollution-Plagued Neighborhood

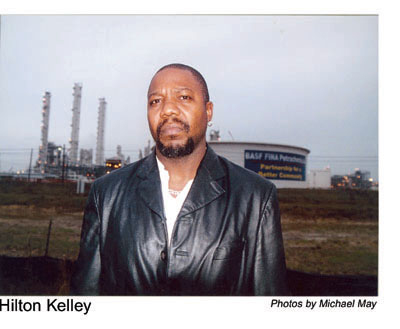

After 20 years in Oakland, California, Hilton Kelley returned home to Port Arthur two years ago. He purchased a small house in his old neighborhood, the Westside, smack against the fenceline of the Premcor oil refinery, an industrial monstrosity of spherical tanks and smoking concrete spires that dwarfs the ranch-style dwellings only a few hundred yards away. Two other refineries encircle the Westside and several times a month one or the other erupts like an industrial Vesuvius, shooting flames high into the sky, jolting Kelley awake, forcing him to gasp for breath, as the whole house shakes. These are “upsets,” unplanned releases that are part of a steady stream of toxic air pollutants emitted not only from the towering smokestacks, but also from thousands of flanges and gaskets at ground level. Not surprisingly, most residents just want to escape the Westside and the toxic fumes that seem to spread sickness in their wake. Kelley knew all this before he came back, and indeed, an asthmatic cough that never bothered him in Oakland has returned. Yet the 41-year-old native chose to live here, among neighbors too poor or old to leave.

His new house is in need of work, but Kelley, who owns a construction company, can easily fix the rotting foundation and peeling paint. A more daunting task is his goal of building a solid foundation for social change in the neighborhood. When he left in 1980, this was a thriving black community, full of locally-owned stores, restaurants, and nightclubs. Now, much of the business on the Westside is conducted after hours by groups of teenagers selling drugs on dark street corners. Most legitimate commerce in Port Arthur fled to malls alongside the highway, leaving an urban core where abandoned lots predominate.

Kelley was lucky to escape, but he didn’t leave willingly. Tragedy forced him out. In 1979, then a 19-year-old college student with no plans of going anywhere, he arrived home one night with his brother to find their mother lying in bed, bleeding from a gunshot wound to the head. It was clear to them that their stepfather, who later pulled a gun on Kelley, had committed the crime, but the police never bothered to question the boys. No one was ever charged with the murder. “It was a black-on-black crime,” Kelley offers in explanation. He left Port Arthur within a few months of her death, and quickly joined the Navy. He worked as an electrician in the service, and then juggled two careers as an actor and small business owner in the Bay Area. Despite achieving a small degree of prosperity, he never stopped thinking about the Westside. “Every time I came home to visit, the neighborhood looked worse and worse,” he recalls. “And another young person I knew was in jail. It started to keep me up at night. I thought about it and figured that someone has to do something, and it might as well be me. So I came back.”

Kelley is walking on Texas Avenue, once the bustling heart of the Westside. These days it’s nothing but a concrete desert, with a bar and liquor store for the lost and thirsty. He strides purposefully through this wasteland, a black leather jacket draped over broad shoulders. His shaved head is uncovered. He talks with a deep, resonant voice, his words well-practiced and full of conviction.

Arriving at his destination, what appears to be a vacant building, he stops and opens the door. Inside a group of kids in karate uniforms, led by Kelley’s younger brother, Warren, practice their moves. Kick. Exhale. Kick. Exhale. This is a community center that Kelley opened a year ago. “When I first got here, I was entirely focused on opening the center,” Kelley says. “I figured the most important thing was for kids to have an alternative to the streets.”

He quickly realized there wasn’t going to be much of a community left to save without confronting the pollution problem. This is a difficult task in an area struggling with high unemployment and a political system that has favored industrial development over people for more than half a century. Most activists in Port Arthur are passive in the face of these obstacles. Others have grown so full of rage at the injustice around them that their confrontational style has alienated potential allies. While Kelley does not retreat from confrontation, he is seeking a third way. For example, he urges people at the center to contact the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (TNRCC) whenever they notice a smell like rotten eggs or paint thinner. Since the TNRCC can’t afford to monitor the air at all times, Kelley believes the more complaints they receive, the more likely they are to enforce the law. “I am not trying to put the refineries out of business,” he says. “We need oil. But oil can be processed more cleanly and efficiently.”

At times, air pollution regulation in the Lone Star state can seem like a Texas two-step: Industry takes a step back with its right foot, while leading with its left. The Texas Legislature has finally closed the infamous “grandfather” loophole that allowed refineries and power plants built before 1971 to avoid federal clean air standards. But George W. Bush, who left the loophole open when he was Governor, is pushing to weaken the federal laws that govern grandfathered facilities. And in 2001, just as the EPA was on the verge of forcing Texas to make significant reductions in the levels of ozone in the Beaumont/Port Arthur area or lose federal highway funds, the TNRCC saved industry by insisting that ozone drift from Houston is partly to blame. The EPA agreed, and excused Beaumont/Port Arthur from further regulation until 2007. One step forward. One step back.

Kelley takes a visitor to Carver Terrace, the housing project where he grew up. Carver Terrace could be mistaken for part of the Premcor refinery yard–its neat rows of standard-issue brick townhouses are surrounded on three sides by the complex. One side was, until recently, home to a “tank farm,” where crude oil, jet fuel, and other petroleum by-products sat in rows of squat holding tanks waiting to be transported. A recent court ruling forced the refinery to move the tanks away from the neighborhood, and the field now sits barren and quarantined, with crop circle-like markings where the tanks once sat. On the other side of the field is Lincoln High School. “When I was growing up, the school band used to practice right there,” Kelley says, pointing to a grassy area adjacent to the former tank farm. “It’s a good thing there was never any accident, because the whole school and housing project could have been incinerated. We would smell the sour odor wafting from the tanks, but my ma would just tell us, ‘that’s the smell of people making money.’ We never even thought it could have an effect on our lives.”

Hydrogen sulfide smells like rotten eggs. Sulfur dioxide smells like a burnt match. Benzene, a carcinogen, smells like paint thinner. Through the years, Kelley and his neighbors breathed a spectrum of foul fumes, the toxic bouquet ranging from rotten to acrid, until many simply became immune to the odors. That didn’t mean their bodies escaped the effects. A recently completed health survey of Carver Terrace residents by Dr. Marvin Legator, professor of environmental toxicology at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston shows the effect of the fumes on the community’s health. Residents of Carver Terrace, and a separate sample from a housing project in Beaumont, were asked about symptoms of 12 diseases, and their answers were compared to a control group in Galveston. “Without question,” says Legator, “the people in Beaumont and Port Arthur are suffering from many more health problems, especially neurological and respiratory diseases, than those in Galveston. The concentration of heavy industry there is having an enormous impact on their lives, and this study proves that to be the case.”

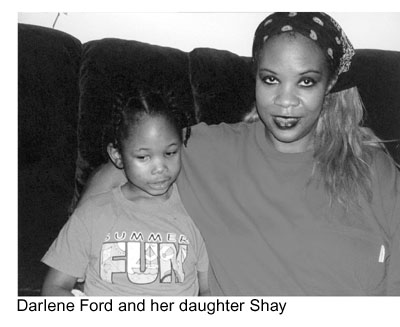

Kelley stops at the apartment of his girlfriend, Darlene Ford, for lunch. She moves purposefully around the kitchen fixing the meal, while her five-year-old daughter, Shay, plays nearby. After lunch, Ford comes into the living room carrying a jumble of bottles, tubes, and pill containers which she spreads out over a coffee table. All of these medicines, she explains, are what it takes for Shay to cope with the air in Port Arthur. “This cream is for rashes, this is for nausea, this is for nose bleeds, this is for cough and congestion,” Ford lists. “The doctor told me that this is too much medicine for her to take just to stay in this town. I am not financially able to leave right now, but as soon as I can, I am moving far away from the refineries.”

She sighs, holds Shay close, and adds: “Somewhere without pollution.”

Even though Shay’s situation is not uncommon, it can be difficult to find people in Port Arthur willing to stand up to the refineries. That’s because there is a fear, perhaps justified, that resistance will cost a family member a good paying job. With unemployment in Port Arthur at 14 percent, few are willing to risk losing a breadwinner. Kelley thinks he has a distinct advantage. “I’m entirely self-employed, and doing fine. So I am immune to the pressure most folks around here face,” he believes.

In some ways, though, it is the perfect time to inspire people to fight pollution. With unemployment as high as it is, residents are losing faith in the long-held belief that industry is good for the local economy, no matter what. Michael Sinegal, a high school teacher in the Westside, comes from a family of refinery workers. His father worked at one until he died an early death from asbestos poisoning. A brother still works there. Sinegal says what frustrates him the most is that some refineries are excused from paying a large portion of their taxes in return for jobs, which, he says, never appear. “These days, the Westside is like a strip mine for the refineries,” he says. “They just take and take, and don’t give anything back. We breathe the poisonous air, and can’t even afford to put our kids through college. I spend thousands of dollars on asthma medication for my son, and, right across the fence, the refinery that caused his problems isn’t even paying their full taxes. It’s like they’re robbing us.”

Kelley’s activism often takes him to city hall, where he lobbies the city council and the mayor, Oscar Ortiz, on behalf of the Westside. Has Ortiz been sympathetic to such concerns? Kelley smiles, mutters something polite about “mutual respect,” and says ask the mayor.

Mayor Ortiz sits at a large polished desk at the end of a long empty room. His face is deeply lined and topped by graying black hair swept to the back. He speaks with a trace of a Texas twang in a practiced tone of dispassionate reassurance. Ortiz is Port Arthur’s first Hispanic mayor, but his only true allegiance seems to be to pragmatism. Although he is a Democrat, he voted for George W. Bush for governor and president. In the time it takes to walk across the room, he is on the phone finding the exact percentage of the tax base the refineries contribute to the town–64 percent. The petrochemical companies pay for most of the city’s services, he relates dutifully.

Ortiz doesn’t see a problem with being out of compliance with ozone standards. It would only be an issue if the air got so bad that refineries were forced to stop expansion. “Then we would be in serious trouble,” he says. “Our economy would suffer immensely.”

“I tell people, if you want jobs, you have to put up with pollution,” he continues expansively. “If we had pollution that was harmful to the human body, the EPA and the TNRCC wouldn’t allow them to keep expanding. You know, there is pollution from everything–people burning grass–everything. I am not going to sit here and blame the refineries.”

Ortiz explains that Port Arthur’s high unemployment rate is not the fault of the refineries–nor apparently does the blame rest with his administration. He says that refineries promise to hire locals, but that the city lacks an adequate pool of applicants. “There are three reasons that the labor hasn’t been provided,” he explains in a resigned tone. “Our people can’t pass drug tests. They don’t have a college degree. They don’t have skills. It’s kind of hard to hire drug addicts without skills.

“You have to want to achieve something in life and become an asset, not a burden, to society,” he continues. “We encourage people to get their GED, to go into drug rehabilitation. But as the old saying goes, ‘you can bring a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink.’ We have 14 percent unemployment, which is ridiculous for our city. It shows me that our people aren’t ready for the job opportunities, and that is kind of sad.”

Kelley scrunches up his face when he hears what the mayor said. “Everyone in the Westside is a drug addict? Come on,” he counters. “And as for advanced training, tell me, whatever happened to OJT–On the Job Training?”

Kelley’s house, with the kitchen and back room blocked off for repair, feels more like an outpost than a home, and in some ways, that is exactly what it is. Kelley keeps a video camera and air sampling device on hand at all times to record releases which occur at the refineries. He picks up the camera and presses play. Inside the viewfinder, a roaring smokestack sends a bright flame and thick plume of black smoke pouring across a clear blue sky. He presses fast forward, the flame flickers and dances as the time marker moves from minutes into hours.

Daytime releases are uncommon, he says. At night, when the TNRCC office isn’t open is when they most often occur. It is not unusual for the lawn to be covered with soot in the morning. “Last August, a valve blew open and a particularly noxious smell wafted through the neighborhood,” he recalls. “I got really sick. I felt a cool sensation deep in my lungs, like breathing ammonia. My heart rate kicked up. I broke out in chills. I went to the hospital, but they are largely funded by the refineries and they just told me it was something I ate.”

Texas law is not at all ambiguous about air pollution standards. The law not only specifies that every state citizen is entitled to air that will not “adversely affect human health,” but allows for the “aesthetic enjoyment of air resources” as well. It would seem, then, that causing serious harm to Port Arthur residents by enveloping them in stinky, toxic air would be against the law. But, alas, it is not so simple. Texas law is interpreted through the TNRCC’s general air quality rules, which, critics contend, are riddled with loopholes.

The largest loophole is the upset clause. Ostensibly, refineries must methodically quantify and control all emissions. However, petrochemical facilities are allowed an unlimited number of “upsets,” which, in theory, are unplanned releases of pent-up pressure that, if left unchecked, could result in devastating explosions. These are allowable as long as the facility makes a report within 24 hours. Such accidents are assumed to be a rare phenomenon; if they occur regularly, the refineries are theoretically required to fix the problem.

In reality, these toxic eruptions have become an integral part of doing business. Refineries and adjacent chemical plants use the upset clause to dispose of badly mixed batches of chemicals (instead of investing in the means to recycle them). This practice is so commonplace that one refinery worker described burning bad product as a matter of protocol. “We have to enter in all the data for a particular mixture,” said a Mobil worker who asked that his name not be mentioned for fear of retaliation. “After it’s all mixed up, we take a sample. If it’s not perfect then–whoosh–we send that whole brew of chemicals right up the stack to burn off. Happens all the time.”

The chemicals are burned at the top of tall smokestacks, with a pilot light just like a stove, and they produce an open flame call

d a flare. In theory, all of the toxic gases are thoroug

ly incinerated and converted into carbon dioxide and water vapor. However, the material is rarely burned properly, contends Neil Carman, clean-air program director of the Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club. “If you see a column of black smoke rising hundreds of feet from a flare,” says Carman, “that is not a clean burn. Those chemicals are escaping into the atmosphere intact. If there is no wind blowing, the gases can sink right down onto the neighborhoods to be inhaled.”

In January 2000, Wilma Subra, a MacArthur “genius” award-winning chemist came to Port Arthur to document the health effects of upsets. Before Subra’s visit, it had been easy for individual plants to raise doubts about whether the releases that made people sick were really from their stacks, or from some other complex (or all the way from Houston). Subra asked the community to keep logs of when they experienced certain symptoms and smells, and matched them with the chemicals that industry admitted releasing to the TNRCC. She proved that the chemicals being released could be linked to symptoms and odors that people nearby were experiencing.

Subra also armed residents with bucket samplers, devices that trap air inside a sterile container to be analyzed later at her lab. The bucket samples provided a chemical fingerprint that pointed to the guilty party (certain facilities produce certain chemicals), and showed that air quality standards were being exceeded at ground level. “This is the first time communities have been able to take a simple snapshot of what goes into their lungs,” says Denny Larson, refinery reform coordinator of the Sustainable Energy and Economic Development Coalition (SEED), an Austin-based group that works closely with Kelley. “With just a few samples we can collapse the house of cards erected by industry that the air is safe to breathe.”

In 2000, thanks to a bill passed by the Legislature, the TNRCC initiated a program to reduce upsets. While some accidents are unavoidable, new TNRCC regulations force companies to prove releases were not preventable, and, if so, how they will fix the problem. The new law also requires TNRCC to consider–for the first time–a company’s compliance history when granting new permits. “We are putting a lot of pressure on facilities that have repeated upsets,” insists Virgil Fernandez, a spokesperson for the TNRCC. “We are sending out investigators to make sure the necessary maintenance is completed.”

There is one drawback to increasing the punishment–it might simply minimize reporting. In the past, the TNRCC has relied on the good faith of the plant managers to report releases accurately. In practice, some have done so, and many have not. It is particularly hard to tell what actually went into the air, because, previously, the TNRCC did not require managers to provide accurate measurements of what the flare burned–making it impossible to know whether the chemicals were pumped into the air for a few minutes or a few hours. New reporting rules changed this, but refineries still may simply decide not to report upsets since the possibility of getting caught is slim.

A TNRCC employee reached by phone whispered conspiratorially from his cubicle that he had examined the data from a number of facilities that purported to have clean records. “They just weren’t reporting them,” he claimed, and then begged for anonymity. However, this same employee was optimistic that the new laws will change the culture at TNRCC. “Upsets are finally being prioritized by the top brass here, which will at last allow us to do our job,” he said.

The Subra study helped focus the community’s attention on the pollution issue, but it also provided Kelley with a challenge. While MODEL, the community group that had brought Subra to Port Arthur, advocated a conciliatory approach, others were angrier than ever. “I really didn’t know who to lean on,” Kelley recalls. “There is so much tension between different activists. I finally decided I had to do things on my own.”

The divisions emerged after a meeting MODEL held to release the findings of the Subra study. The meeting was designed to spark a dialogue between the community and industry, which, it was presumed, would no longer be able to deny that their emissions were a problem. But after the initial meeting, the petrochemical facilities declined to negotiate directly with MODEL. Instead, they decided to form their own organization and invited select community members to join. The group, officially known as the Port Arthur Industry and Community Leaders Advisory Group, has now been meeting for more than a year, presumably ushering in a new era of cooperation.

Sue Parsley, Public Affairs Manager at the Motiva refinery and member of the advisory group, thinks this is the case. Over the phone, she maintains the cheerful optimism that is the hallmark of her profession. She lists all the wonderful things that industry and the community can accomplish by working together: improve the schools, set up an emergency line to warn about industrial accidents and bad weather, etc. She fails to mention emissions or unplanned releases. When pressed, Parsley tersely says that they have always done their best to control pollution. “We are preparing a presentation, so we can show how our technology is, and has been, state of the art,” she says.

Kelley was working with MODEL when he first arrived in town, but in time, he came to believe industry had gotten the better of the group. “The folks at MODEL have done a lot for the community,” he says. “But, lately, they seem satisfied just to be sitting across the table from industry. I don’t believe that’s going to change anything. The only thing that will make them change is legal action.”

Others agree. In Corpus Christi, for example, a group of residents has filed a class action suit against Valero Energy Corporation over upset emissions. After hundreds of hours of research, the group’s lawyers were able to document that the refinery’s upset emissions in 1995 were more than ten times larger than normal permitted emissions. (The company was never fined by the TNRCC for those upsets.)

Some in Port Arthur have lost faith in the system. One such industry critic is Reverend Roy Malveaux, who advocates a more drastic solution. “It is in everyone’s best interest to create a mile and a half buffer zone around the refineries,” says Malveaux. “It’s good for industry, because they are free from liability from both emissions and accidents. It would provide more security if a terrorist decided to target a refinery. And it would finally put an end to the legacy of environmental racism we have here in Beaumont and Port Arthur.”

Such a solution would mean moving entire neighborhoods at tremendous cost to industry. Although Kelley agrees that a buffer zone would be ideal (it has been done elsewhere), he thinks the simple enforcement of existing laws could also make a huge difference in people’s lives.

In a narrow, barren room at the community center, Kelley outlines his plans. “I am going to set up a computer lab with Internet access in here,” he says. And the kitchen, just a sink now, will one day be able to feed groups that come for training and educational seminars.

Every month he turns the center over for long meetings about the pollution that plagues Port Arthur. In the days before the gatherings, Kelley takes a stack of flyers and stands in front of the local grocery store, hoping to find folks willing to help him document what upsets are doing to the community. Most seem interested, he says. And at each meeting, one or two new people participate. It’s a start, albeit a slow one. Kelley hopes that with a little luck and a lot of activism, his story will become a trend, and others will return to Port Arthur. “I want to be right here when the businesses and families start coming back to the Westside,” he says.

Michael May is a freelance writer living in Austin.