Unchained Memories

Everywhere in Texas in early 1854, Frederick Law Olmsted heard rumors of fugitive slaves. Commissioned by the New York Daily Times (as it was then known) to write about the world that slavery built, the New York journalist spent four months in the Lone Star State. A free soiler, Olmsted believed that the antidote to the ‘peculiar institution’ lay in free labor working its own land. His dispatches to the Times, later republished as A Journey Through Texas; Or a Saddle-Trip on the Southwestern Frontier, stressed the relative inefficiencies of the slave economy. German, non-slaveholding cotton farmers out-produced their slave-owning neighbors, Olmsted asserted after analyzing crop-yield statistics and gathering anecdotal evidence throughout the state. But such data paled before the most important mark of slavery’s failure–its workforce kept running away.

This seemed particularly true in south Texas. Although there were fewer than 2,000 slaves in Bexar County when Olmsted rode into San Antonio, it appeared as if they all were trying to get away. Geography was an incentive. Living a mere 150 miles from the Mexican border, slaves needed only to dodge tight surveillance and survive the rugged trek across a desiccated landscape to gain their freedom; given their route, the North Star had no meaning for these bondsmen and women.

But their repeated efforts to reach El Sur had considerable significance, as Olmsted recognized. On San Antonio’s dusty streets and on the roads that led to and from the busy regional hub, the talk among whites was of black flight. In a hostelry southwest of town, the journalist listened in on a conversation among slave hunters who had been chasing their quarry for two weeks, and had lost him in the brush country. To them, the fugitive’s desire to strike out for Mexico made no sense, a reflection of his idiocy. “Now, how much happier that fellow’d ‘a’ been, if he had just stayed and done his duty,” one asserted; “these niggers, none of ’em, knows how much happier off they are than if they was free.”

What that assertion conveyed of white denial, Olmsted did not say, expecting his northern readers would draw the obvious conclusion. But just in case they didn’t, he returned to this issue when reflecting on a subsequent interview in Piedras Negras with a successful runaway. After learning of the bleak situation that plagued recent arrivals to Mexico–they lacked the requisite language skills, could not easily secure work, and had little money–Olmsted unfurled his abolitionist colors. “The escape from the wretchedness of freedom is certainly much easier to the [N]egro in Mexico than has been his previous flight from slavery,” so why, he asked his audience, did he “not hear a single case of [a slave] availing himself of this advantage”?

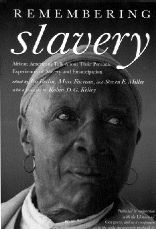

The question was rhetorical. The observant New Yorker knew why the enslaved much preferred the short-term misery of freedom to the long-term brutality of bondage, and why they repeatedly demonstrated their preference by voting with their feet. Confirmation of Olmsted’s insight emerges in innumerable interviews with ex-slaves collected in Remembering Slavery, a compilation based on the pioneering recordings taken by John Henry Faulk, Zora Neale Hurston, and John Lomax, among others. Arnold Gragston was one of those whose experiences was documented. A Kentucky slave by day and an industrious oarsman by night, he would ferry runaways across the Ohio River on “black moon” evenings; he later guessed that he may have aided several hundred before making his own break to the other side. Asked by an interviewer in the 1930s what the escapees’ destinations had been, Gragston rattled off the usual urban centers where unskilled labor could find work, from Chicago to Cleveland to New York. But Canada was also high on the list, “because all of the slaves thought it was the last gate before you got all the way inside of heaven.” Although he doubted “there was much chance for a slave to make a living in Canada,” still “they seem like they rather starve up there in the cold than to be back in slavery.”

Those who did not live close to the Mexican or Canadian border may have had fewer options, yet the homebound were not passive in the face of white oppression. If under-provisioned, for instance, slaves simply appropriated what they could from the master’s larder or coop or pen. Snatching a chicken was child’s play compared to “grabbin’ a pig,” Richard Carruthers recalled: “You have to catch him by his snoot so he won’t squeal and clomp down tight while you take a knife and stick him till he die.” The illicit was justifiable. “When you don’t git ‘lowanced right, you has to keep right on workin’ in the field,” Carruthers observed to a female interviewer, “and no nigger like to work with his belly groanin’. No ma’am, the good Lord won’t call that stealin’, now will he?” Others used the Good Book in defense of theft. Jeff Calhoun remembered a riveting moment when a fellow slave caught harvesting a prized batch of collard greens was lambasted for violating the commandment Thou Shall Not Steal, and then accused his master of ignoring an equally vital biblical injunction: “You shall reap when you laboreth.”

Small moments of resistance rippled through daily life. Evading vigilant, nighttime patrols so as to spend time with a lover, mother, or spouse was one way to sustain–if incompletely–familial or affective ties. Another was to name children clandestinely after relatives (or previous owners) to maintain kinship networks and thus avoid marriage even with second cousins. These naming patterns subverted the masters’ desires to control slaves’ identities by bestowing only a first name on them, acts of quiet defiance that found their parallel in the breaking of tools or careless cultivation that just happened to damage crops. These modest forms of insubordination complicate our understanding of the master-slave relationship. Even those who played the part of a daft and docile servant could earn important concessions, and gain the upper hand in this sense–their actions, like the legendary tales in which Br’er Rabbit outwits the fox, revealed who was the fool and who sly.

Despite the importance of these tales of inversion, none of those whose life stories are narrated in Remembering Slavery ever forgot they were property. White domination of their beings was manifest in exacting work loads, capricious demands on labor and time, sexual violation of bondswomen, and destruction of black families on the auction block. Betty Simmons knew something of each of these traumas. She had grown up in Alabama, but when her store-owning master suffered financial losses, he sold her to speculators who hauled her to Memphis’ vast “nigger traders’ yard.” She was one of 200 slaves culled for the New Orleans market; there, she was purchased by Colonel Fortescue from Liberty, Texas. As the transactions mounted, as she became just one more body moving through the complex infrastructure of the southern slave trade, Simmons felt most the emotional costs: “I’s satisfy den I los’ my people and ain’t never goin’ to see dem no more in this world, and I never did.”

Emancipation could not bind up all such wounds. But liberation was a deeply moving moment, and Katie Rowe, a former Arkansas slave, surely spoke for many when in the mid-1930s she affirmed she “never forget de day we was set free.” Called to the overseer’s yard, she and the other field hands stood in the morning sun and listened to an unknown but smiling man ask them an odd question: “You darkies know what day it is?” Knowing they didn’t, he plunged ahead. “Well, dis de Fourth day of June, and dis is 1865, and I want you all to ‘member de date, ’cause you allus going ‘member de day. Today you is free, jest lak I is, and Mr. Saunders [the overseer] and yur Mistress and all us white people.”

That wasn’t quite true. African-American freedom would be severely circumscribed in the coming years, as post-war reconstruction collapsed in response to virulent southern white resistance and growing northern disengagement. The loss of the right to vote followed suit, as did the enactment of the infamous Jim Crow laws; for the next 80 years, social space was tightly segregated.

These Black Codes endured because they received state and federal court sanction and because they were inscribed in the hearts and minds of the most well-meaning of whites. That’s what John Henry Faulk discovered about himself one evening after concluding his interview with a former slave. Trying to put his illiterate interviewee at ease, he assured him “what a different kind of white man” he was, and then ticked off a list to prove his point. “I believe you ought to be given the right to go into whatever you qualify to go into, and I believe that you ought to be given the right to vote.” Faulk was startled by the elderly man’s reply: “You know, you still got the disease, honey. I know you think you are cured, but you’re not cured.” As he articulated what ailed Faulk, this unnamed black man identified the source of the tragic misunderstanding that continues to trouble race relations in the United States. “You talking about giving me something I was born with just like you was born with it. You can’t give me the right to be a human being. I was born with that right.”

Observer contributing writer Char Miller teaches history at Trinity University.