Pale Writer

I am the first and only serious writer that Texas has produced,” declared Katherine Anne Porter in a 1958 interview with The Texas Observer. Like her 1975 assertion to Howard Payne University President Roger Brooks (“I happen to be the first native of Texas in its whole history to be a professional writer”), Porter’s boast was in part a reaction to her disappointment that the Texas Institute of Letters had bestowed an award on J. Frank Dobie instead of her. If a professional writer is one who makes a living out of the literary affliction, Dobie had a greater claim to the title than Porter, who lived to write but made a living out of her writing only after the publication of her only novel, Ship of Fools, in 1962.

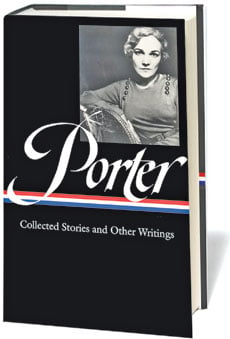

Regardless, Porter (1890-1980), who made it onto a postage stamp in 2006, now beats Dobie, Horton Foote, Cormac McCarthy, Tomás Rivera, William Goyen, Rolando Hinojosa, Larry McMurtry and every other Texan to enshrinement in the Library of America’s definitive editions of the national literary canon, this country’s version of France’s Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. The Library of America offers volumes for more than 100 authors, from Henry Adams and James Agee to Edmund Wilson and Richard Wright. Massachusetts and New York are abundantly represented in the roster, which also includes writers from Nebraska (Willa Cather), Rhode Island (H.P. Lovecraft), and Maine (Sarah Orne Jewett).

Asked to name the greatest French writer, André Gide replied, “Victor Hugo, alas.” Porter’s anointment, 26 years after the Library of America published its first volume, might suggest that the woman who left Texas at age 19 and returned only once in the next 55 years is the Greatest Texas Writer. Alas.

Though Henry James occupies 14 Library of America volumes, Porter is contained in just one. She was long-lived but not long-winded, despite the trunkful of manuscripts she reported torching. It took her 20 years to complete Pale Horse, Pale Rider, 50 pages long, which works out to 2.5 pages per year. If Stephen Crane, who died at 28, had toiled with similar celerity, the Library of America volume devoted to his work would be barely a pamphlet. Porter never finished the biography of Cotton Mather she began in 1927, and she kept the pot boiling for 27 years before completing Ship of Fools and telling McCall’s Magazine, “I finished the thing; but I think I sprained my soul.”

Although that novel, an overwrought allegory about a microcosm of humanity sailing from Mexico to Germany in 1931, made her rich and famous, Porter’s strength was shorter fiction. She preferred the term “short novel” to “novella,” which she called “a slack, boneless, affected word that we do not need to describe anything.” Whatever the term, her literary legacy resides in a handful of works that can each be read in less than two hours. Edited by Porter scholar and biographer Darlene Harbour Unrue, Collected Stories and Other Writings contains four short novels (Old Mortality; Noon Wine; Pale Horse, Pale Rider; and The Leaning Tower) and 22 short stories that are her most enduring contributions to American literature. The hefty volume also includes essays, reviews and other nonfiction prose, but not Porter’s one full-length novel or her verse.

“Within the past dozen years,” Porter wrote in 1933, “I have lived in New Orleans, Chicago, Denver, Mexico City, New York, Bermuda, Berlin, Basel, and now live in Paris.” Her stories and essays draw on most of those locales, as well as Texas.

“MarÃa Concepci&oactue;n,” featured in The Century Magazine in 1922, was Porter’s first published fiction. Set among the Indians of Mexico, it is the chilling story of a woman who kills her husband’s lover, MarÃa Rosa, and snatches MarÃa Rosa’s baby to replace the one she herself lost in childbirth. Like “MarÃa Concepción,” several other works from Porter’s first collection, Flowering Judas and Other Stories (1930), including “Virgin Violeta,” “The Martyr,” “That Tree,” and “Hacienda,” are set in Mexico. The title story, Porter’s most widely anthologized, focuses on Laura, a beautiful expatriate who teaches English to children in Xochimilco and runs errands for revolutionaries in whose cause she has ceased to believe.

Mexico was to Porter what Paris was to Hemingway and Fitzgerald. In 1921, Porter began writing a novel she called The Book of Mexico, but she abandoned it two years later. Befriended by Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, and bedded by Felipe Carillo Puerto, governor of Yucatán, she developed a genuine affection for the land and people, and she wrote about both in journalistic dispatches to the United States. Collected Stories and Other Writings includes Porter’s trenchant observations about the arts and politics of Mexico, and even her translation of a sonnet by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Early in “Reflections on Willa Cather,” Porter writes: “I have not much interest in anyone’s personal history after the tenth year, not even my own. Whatever one was going to be was all prepared for before that. The rest is merely confirmation, extension, development. Childhood is the fiery furnace in which we are melted down to essentials and that essential shaped for good.”

For good or ill, Porter spent her own first decade in Texas-mostly in Kyle, in Hays County. Though she shunned her native state for most of her life, she directed that her ashes be interred at Indian Creek, near Brownwood, where she was born. Several of the works that seem destined to outlive their author the longest draw on Porter’s childhood experience of Texas as a confluence of the Old South (“I am the grandchild of a lost War,” she writes in an autobiographical sketch) and the Southwestern frontier. Old Mortality recounts a young woman’s disillusionment with the chivalric dreams of belles, balls and duels on which she was raised. Set on a hardscrabble farm in South Texas, “Noon Wine” begins in 1896 with the arrival of a taciturn stranger from North Dakota. Olaf Helton becomes indispensable to the torpid farmer, Royal Earl Thompson, until a revelation about Helton’s past jolts Thompson into violence.

“The Jilting of Granny Weatherall” seems a translation from Russian into Texan of Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich-a fundamental assessment of life staged on the verge of death. The same could be said of Pale Horse, Pale Rider, except that in the latter, 24-year-old Miranda manages, barely, to survive the influenza that concentrates her mind in a Denver hospital but kills her beau, Adam. “Don’t you love being alive?” Miranda asks, in Porter’s quickening prose.

Old Mortality is not only the title of a Porter short novel but also an enduring preoccupation of the Porter oeuvre, where death-sometimes self-inflicted-is a familiar presence.

In “The Never-Ending Wrong,” Porter evokes the tumult over immigrant anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti and her own arrest while protesting their imminent execution. Her leftist activities ceased abruptly upon the commencement of her friendships with Southern conservatives Robert Penn Warren, Andrew Lytle, Caroline Gordon, and Allen Tate. By 1940 she was writing, “All political history is a vile mess, varying only in degrees of vileness from one epoch to another, and only the work of saints and artists gives us any reason to believe that the human race is worth belonging to.”

A virtuoso at alienating husbands, lovers, friends and editors, Katherine Anne Porter was no saint. But Collected Stories and Other Writings preserves and honors the work of a singular artist.

Contributing writer Steven G. Kellman reviewed Darlene Harbour Unrue’s Katherine Anne Porter: The Life of an Artist for the December 16, 2005, Observer.