‘There Have to Be Limits’: Lawsuit Urges Scorching Prisons to Cool Down

New plaintiffs have expanded a 2023 lawsuit against TDCJ, accusing the agency of “cooking [prisoners] to death."

Last June, Bernhardt Tiede suffered a likely stroke while living in a prison cell that regularly got up to around 110 degrees Fahrenheit. The 65-year-old—whose story inspired the 2011 Richard Linklater film “Bernie”—is housed at the Estelle Unit in Huntsville. Now, several new parties have joined and expanded a lawsuit Tiede filed last year against the prison system and Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton related to its inadequate heat-safety measures.

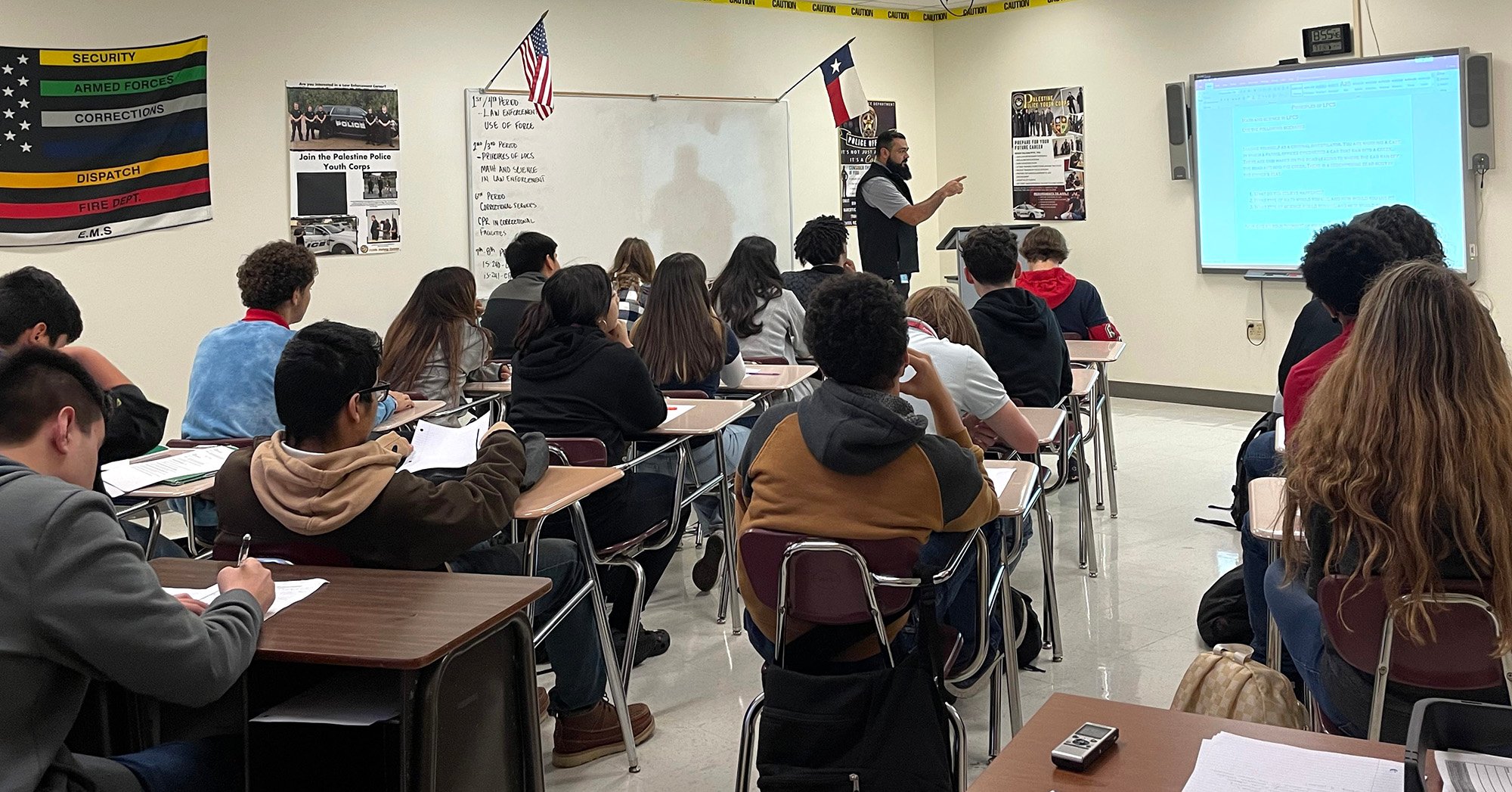

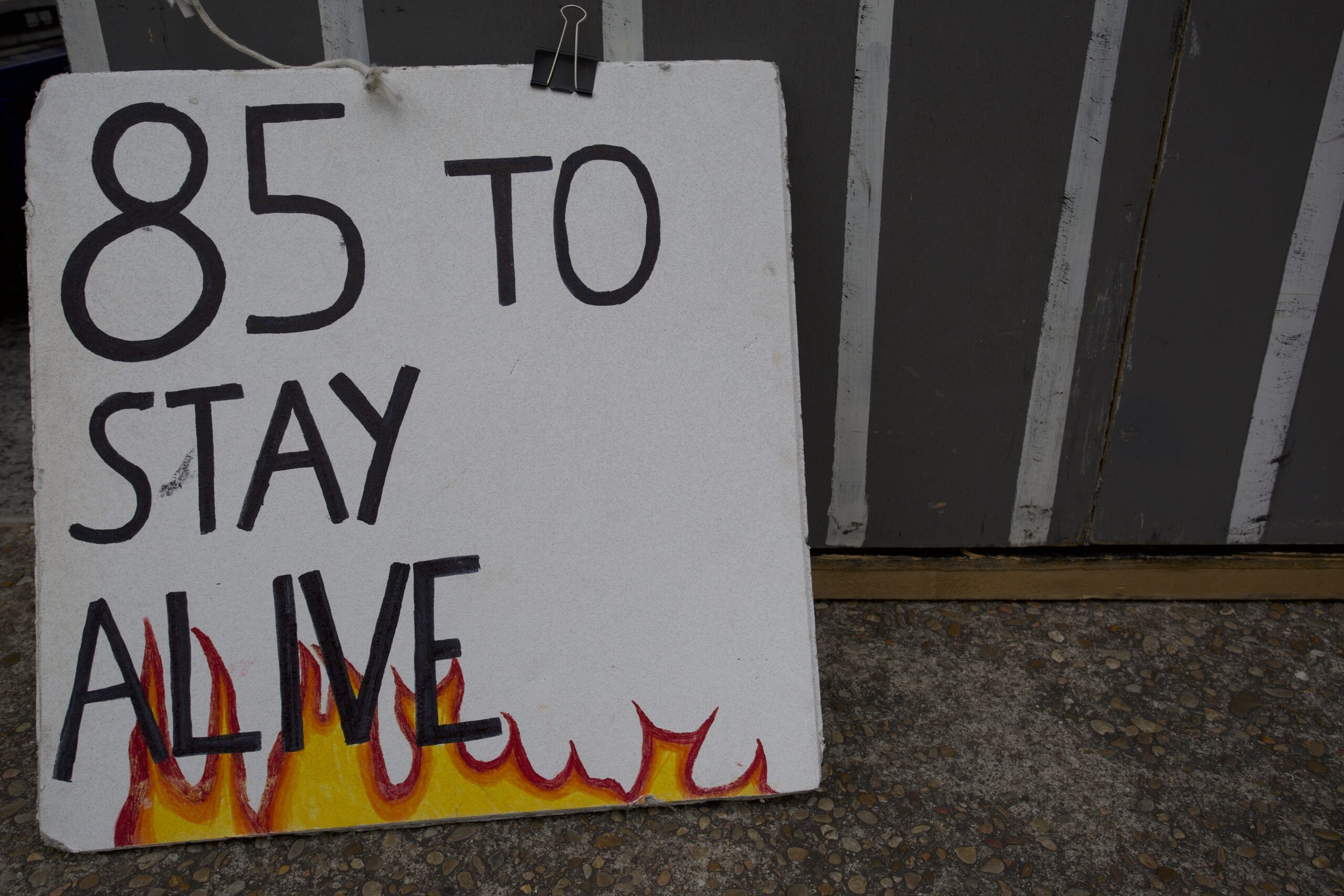

On Monday, Tiede’s attorneys filed an amended complaint, along with the nonprofits Texas Prisons Community Advocates, Lioness: Justice Impacted Women’s Alliance, Texas Citizens United for Rehabilitation of Errants (Texas CURE), and the Coalition of Texans with Disabilities. This new complaint expands the suit beyond Tiede’s case, with potential implications for everyone incarcerated in Texas prisons. In the suit, the plaintiffs ask the court to declare that its current heat mitigation policies are unconstitutional and to require the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) to cap prison temperatures at 85 degrees. For 30 years, Texas jails have been required to keep facilities cooler than 85 degrees. Federal prisons in Texas also have a 76-degree maximum, but the state’s prisons have no such upper limit.

“If cooking someone to death does not amount to cruel and unusual punishment, then nothing does,” the complaint said.

Tiede lives with diabetes, hypertension, and emphysema, among other conditions, that all make him more vulnerable to heat. At one point, Tiede was taken by an ambulance to a hospital due to heat-related illness. Afterward, “he was returned to the same oven-like cell,” the new complaint says. The incident resulted in permanent partial paralysis, as well as some chronic illnesses, according to the suit. Last August, Tiede filed a civil rights suit in the U.S. Western District Court in Austin and won a temporary injunction, moving him to an air-conditioned cell. But that injunction was a temporary relief. TDCJ has the power to move Tiede, and any of the system’s other nearly 130,000 prisoners, to uncooled cells this summer. Last year was the second-hottest summer on record in Texas, and climate experts are predicting 2024 will be another brutal one.

In Texas, less than one-third of the units have fully air conditioned housing areas. Previous lawsuits have led to some progress. Since 2018, TDCJ has installed 8,433 “cool beds”, and another 2,149 are under construction (mostly in state jails). Last year, the Texas Legislature allocated $85 million to the prison system for maintenance projects that have gone toward installing AC in the state’s prisons. (This was after the Texas House approved a budget that would have put more than half a billion dollars toward installing climate control in prisons, but the effort died in the Senate.)

The reality inside an unairconditioned Texas prison is a miserable one. According to the lawsuit, TDCJ processed nearly 6,000 heat-related grievances in less than a year, from September 2020 to the following August. Men and women housed in stifling units have to improvise ways to try to stay cool, like flooding their cells with toilet water so they can lie in the relatively cool puddles. “Many spend their summer days avoiding any exertion that could bring on heat-related illness (including walking to the chow hall for meals),” the lawsuit said.

Because of the way many prisons are constructed—old-style brick buildings that trap heat—nighttime in prisons isn’t much better than mid-afternoon.

“At night it gets bad. I lay there and it feels like I want to throw up, and I’m so thirsty that when I get up to drink water out of the sink it makes it worse,” one man wrote to the Texas Observer last year. “The fans they sell us … they feel like you are laying under a hair dryer, so really not helping.”

The lawsuit alleges that at least 40 people died, and hundreds more fell ill, in Texas prisons last year because of the heat. This directly contradicts TDCJ, which told the Observer Monday the agency “has not had a heat-related death since 2012,” despite reporting deaths since then to the Attorney General’s office that list heat as a contributing factor on autopsy reports.

In June of last year, 37-year-old Elizabeth Hagerty was set to be released. She was transferred from an air conditioned unit to an uncooled one. Shortly after arriving, Hagerty—who suffered from diabetes, hypertension, and asthma—began having trouble breathing, the suit said. She died June 28, a 100-degree day. According to the lawsuit, Hagerty “had a sign in her cell window that read, ‘please give me water,’ but she was ignored.” The suit says high temperatures were cited as a “contributory factor” to her death.

That same day, June 28, 37-year-old Jon Anthony Southards died at the Estelle Unit. His mother, Tona Southards-Naranjo, who told the Observer she spoke with her son on the phone three times the day he died, is quoted in the lawsuit saying when she saw her son’s body, he had a heat rash “from the top of his head to the backs of his knees.”

Naranjo told the Observer the medical examiner stated in her son’s autopsy report that heat couldn’t be ruled out as a factor. The family had a separate autopsy done, as well, and the second medical examiner agreed. But still, TDCJ hasn’t released her son’s core body temperature, so they can’t be certain. She said she drove down to the unit the night her son died and took the temperature across the street from the unit. She said it was 98 degrees at 2:35 a.m. “The judge sentenced him to 20 years,” Naranjo said. “A cell sentenced him to death.”

The lawsuit lists 20 deaths between 1998 and 2012, in which the body temperatures ranged from 104.1 degrees to 109.9 degrees. At least 19 of these people were on medication known to reduce heat tolerance.

“It is likely that there are many more heat-related injuries and deaths than TDCJ has acknowledged because hyperthermia is known to be an underreported cause of death by medical examiners and pathologists,” the amended complaint said.

This isn’t the first time an outside group has questioned TDCJ’s lack of reported heat deaths. In 2022, a group of researchers determined that 271 people who died in TDCJ custody between 2001 and 2019 could have died of heat-related issues.

Heat ranks first among deadly environmental threats. By itself, it’s plenty dangerous. But conditions like hypertension and asthma, as well as many common medications, make it much harder for people to regulate their temperatures.

TDCJ’s own heat mitigation policies don’t dispute that heat can be detrimental to people’s health. But even so, many of the units rely heavily on ventilation and personal fans, strategies that end up just circulating scorching air. For this reason, the inside of Texas prisons are often hotter than outside. The lawsuit includes an excerpt from a 2011 temperature log from the Hutchins Unit in Dallas, where it was noted that the heat index reached “149+” degrees by 10:30 a.m.

TDCJ’s website lists “enhanced heat protocols” that go into effect from April through October. These measures include increased medical screening, restricting outdoor activities, and training prisoners and guards on how to notice and react to symptoms of heat illnesses. According to the lawsuit, TDCJ’s current policies to mitigate heat—like offering fans and distributing water—are not enough.

“TDCJ’s heat response amounts to a hospital triage policy during wartime or mass casualty events, where responders must decide who to treat and in what priority order,” the lawsuit said. “It does nothing to address the underlying cause of heat-related illness and death—the heat itself. Unlike responders during wartime, TDCJ can control the heat. It simply refuses to do so.”