Out in East Texas

In Search of Edward Swift.

I discovered Edward Swift-the Texas writer who made me love the place I’m from-after moving from Huntsville to New York City. At the time, I was struggling to write a comedy on the unlikely subject of growing up gay in East Texas. For obvious reasons, I felt confident that mine was an original approach to a well-worn theme. Then I went to lunch with my friend Richard, who said a terrible thing. “Oh, you must love Ed Swift’s books,” Richard said.

“Ed Swift who?” I asked.

“Oh, you know,” he said. “That brilliant guy who writes all those hilarious comedies about growing up gay in East Texas. Like Splendora.”

Devastation ensued.

I went home, Googled Ed Swift, Amazoned Splendora, and soon after read what has become my One Great Book, the one I can’t imagine not having read. The comic masterpiece (celebrating its 30th anniversary this year) that fundamentally reordered my sense of home and place, and made me feel-to paraphrase Alice Walker upon discovering Zora Neale Hurston-that whereas I’d formerly believed mine to be the solitary task of clearing a way through the wilderness, I was, in fact, following a fabulous forebear.

It was a feeling that deepened as I read Swift’s six other books, including the terrific Principia Martindale and My Grandfather’s Finger. What was it that I found so moving about Swift’s work? Well, aside from the rare opportunity to see my home again as if for the first time, and from the perspective of an artist so funny and tender that I was forced to reconsider a familiar landscape, it was the recognition of a worldview that remains unique to East Texas-that hysterical sense of Grand Guignol half-buried in the toxic red dirt of Beaumont. In college, I’d devoured the books of those devilishly Gothic writers of the South–Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, the early works of Truman Capote, and even John Kennedy Toole. Why, I wondered, was there no Gothic tradition in Texas literature? After all, there’s no place more Gothic than East Texas. There’s no place more violent and decorous, or endowed with a more appalling rhetorical flair. In case you’re a person who never knew the mixed blessing of being born to the “Land of the Permanent Wave,” to use Bud Shrake’s splendid handle for the region, here’s a small story illustrative of the East Texas sensibility:

For many years, the grandparents of a good friend of mine owned and operated a pawn shop in Beaumont. This pawn shop-like countless others across the nation-was, from time to time, robbed by vicious, gun-wielding individuals. During one of these robberies, a pistol-packing thug placed the barrel of his revolver directly to the silver, curled-and-set temple of my dear friend’s grandmother. Without panic or hesitation, this steely grandma said to the sniveling thug, “Darlin’, if you blow out my brains, you’ll just ruin my hair.”

The thief quickly exited with his loot, doubtless duly impressed.

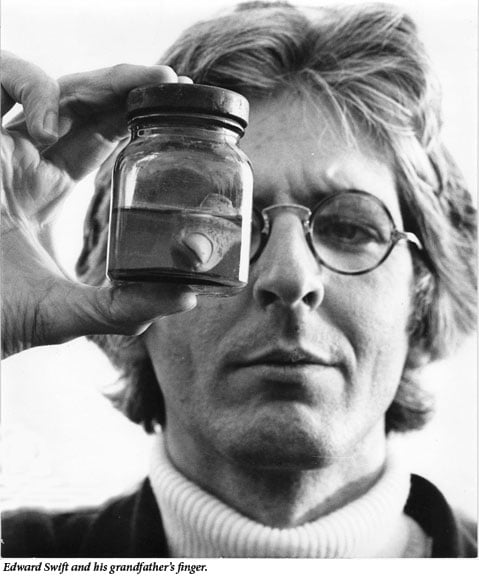

That’s East Texas for you, and that’s also Edward Swift, the missing Gothic link in Texas literature, whose characters are never far from ammo or Aquanet. Take, for example, Miss Jessie Gatewood of Splendora, the New Orleans drag queen who returns to his tiny Texas hometown to reap hilarious revenge on the homophobes who did him wrong; or Miss Corinda Cassy in Principia Martindale, the evangelizing leader of Cowgirls for Christ; or Eugenia Fane McAlister, the maniacal, piano-playing matriarch of Mother of Pearl. Throughout his oeuvre, Swift reveals himself as East Texas Gothic to the tips of his fingers. Or rather, to the tip of his grandfather’s finger-the formaldehyde-preserved centerpiece of his marvelous memoir-with-recipes, My Grandfather’s Finger, Swift’s wild, whirling story about coming of age in and around woeful Woodville, Texas.

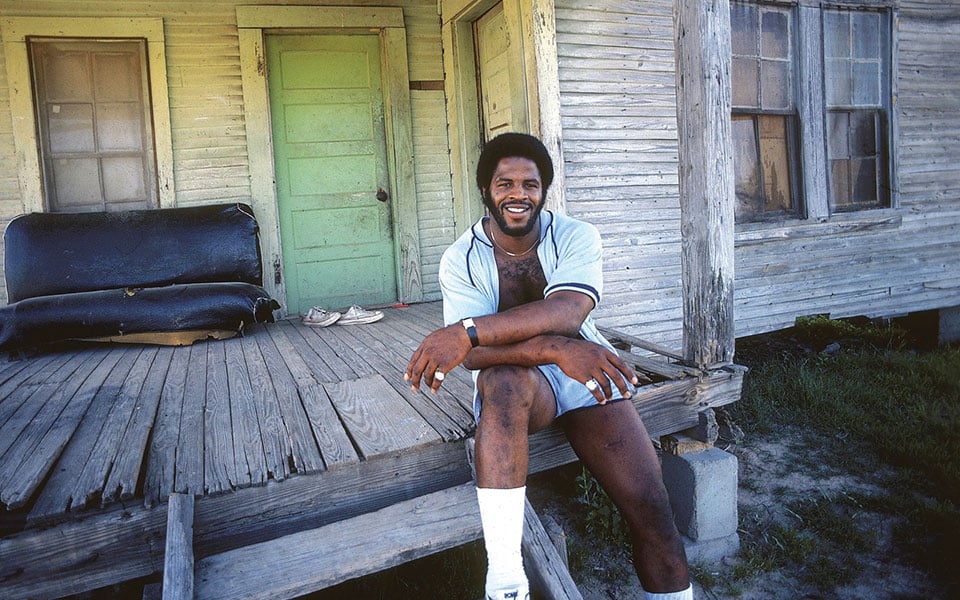

On a misguided and ill-advised literary pilgrimage, my best friend Jessica and I recently paid a visit to Woodville.

My friends, there is not much to Woodville.

In fact, if you’re ever in search of a concrete example of the power of imagination to overcome bleak circumstance, I’d suggest reading Ed Swift and then driving to Woodville.

Born in 1943, Swift spent his earliest childhood in the Big Thicket idyll of Camp Ruby, a small, faltering logging community tucked into the Great Piney Woods-from which his family would be flung by the Texas Forest Service into the mortal coil of nearby Woodville when Swift was 8 years old. Having visited the town, I find it difficult to believe anyone has ever grown up happily there, but Swift-an early balletomane twirling through town in a green wool skirt-certainly did not. And after attending Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, he hurried, in the late ’60s, to New York City, where he clerked at Scribner’s Bookstore with the rock-star-to-be Patti Smith and met his great writing teacher, the extraordinary novelist Marguerite Young (author of that odd opus, Miss MacIntosh, My Darling).

It’s difficult to imagine a more perfect teacher for Swift than Marguerite Young. They shared a literary sensibility that blended small-town gossip with Proustian cadence. In a 2001 elegy to Young published in Gulf Coast magazine, Swift quotes the advice she offered the writing students who enrolled in her New School workshop, and often stayed (like Swift) for years. Among them: “All things strange are very beautiful. All things beautiful are very strange.” And: “The imagination is everything. What you call reality is merely imagined, and what you call unreal may be the greatest of all realities.” And perhaps the insight that proved most significant to Swift: “A writer must come from a special world … Joyce had Dublin, Proust had Paris, Flannery O’Connor had Milledgeville, and Faulkner had his county.”

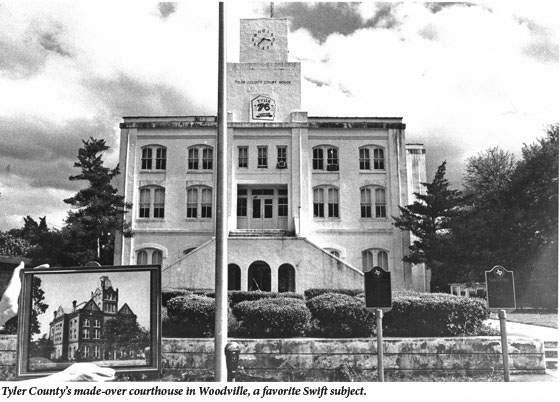

It would be Swift’s writerly task to return, in his imagination, to his “special world” of East Texas-to Camp Ruby and Woodville, which would provide his books with a central metaphor. It seems that during the Great Depression, in a fit of New Deal exuberance and with very little provocation, the Works Progress Administration plastered over the Tyler County Courthouse, transforming a delightful example of Gothic architecture into a fairly drab Deco structure. It was a makeover that would prove formative to Swift-one he would return to in Splendora and My Grandfather’s Finger. In the latter, Swift writes:

“The courthouse is … like someone who is hiding something that he has no business hiding but has been made to feel like he has business hiding it so he does. The courthouse is like someone in disguise, someone who is ashamed of what he looks like so he’s allowed everyone else to make him over to look like what they wanted him to look like whether he wants it or not.”

Like its courthouse, Woodville would remain, throughout Swift’s writings, a maddening model of backbiting, small-town repression, while Camp Ruby would be mythologized (in A Place with Promise and My Grandfather’s Finger) as an East Texas Eden-a green and easy home of hot melons and tall tales from which Swift would inherit his dissent and his story-telling craft. He offers this history of the Big Thicket:

“The early settlers called it No Man’s Land, a hiding place for ne’er-do-wells of all descriptions. During the Civil War, the Thicket was a well-known refuge for pacifists and Jayhawkers, those who refused to fight for the South. It was also a haven for renegades, recluses, and religious fanatics … the wildest of dreamers, and the maddest of madmen. And although they were rabid individualists, they were similarly marked with loose tongues and poetic speech … They knew instinctively how to tell as well as how to enlarge upon a story while keeping it rooted in truth … that a story is a living thing and should grow with each telling.”

It seems merely a nod toward Thicket tradition, then, that Swift’s novels fairly burst with outrageous talkers (notably Clarissa Spellbinder of Miss Spellbinder’s Point of View) who prefer the well-told yarn to literal truth. One of Splendora‘s most amusing passages consists of a series of slanderous letters passed among the members of the ladies’ Epistolary Club-letters resembling a runaway game of Rumor, each one more mouthwateringly defamatory than the last.

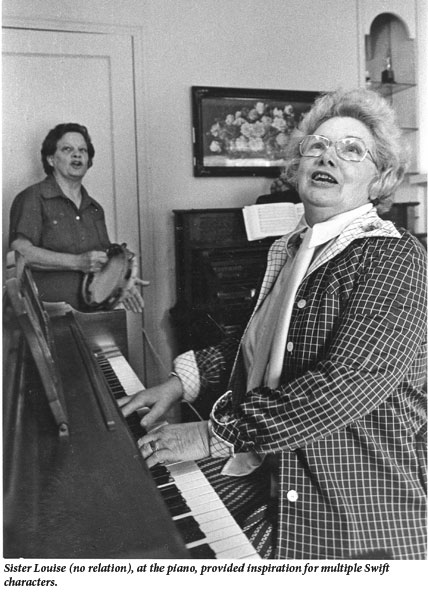

It’s to Swift’s enormous credit that he celebrates the embellishments of his (mostly female) characters. Though he parodies their talk, it’s always done kindly, without a whiff of big-city condescension or misogyny. To the contrary, Swift seems endlessly enthralled by the oratorical talents of Texas women, from his scarlet ladies (like Splendora‘s resident va-va-voom girl, Maga Dell Spivy) to his Holy Rollers (like Sister Louise Owens, a woman capable, in Swift’s memoir, of self-dramatizing even while speaking in tongues). Far from merely satirizing these mouthy ladies, Swift seems to have drawn inspiration from them.

In a 2002 interview with Swift in the Austin Chronicle, Clay Smith recounts the following story:

“Four years ago [Swift] submitted a manuscript, The Daughter of the Doctor and the Saint, to four houses under the name Maria de la Luz … about an impresario … who runs one of the nation’s most famous bordellos. … Through his agent, Swift had submitted the very same manuscript to 12 editors two years before he concocted Maria de la Luz and got no response. But when Maria de la Luz wrote it, all four editors wrote back right away … one of them, from Algonquin, was intrigued enough to call Maria de la Luz at home, which is when things got interesting. Swift had put his home phone number on the front page of his manuscript. … After several phone conversations with the editor in which he stalled, saying that Maria de la Luz was sick, [Swift] finally fessed up. There was a long silence on the other end of the line. ‘Oh, I was afraid I was going to hear this,’ she said … .”

The reason Swift felt driven to invent such a ruse was that after the publication of Principia Martindale, his second novel, after grabbing rave reviews in major newspapers (including The New York Times) and national magazines, he seemed, suddenly, to become invisible. “My first two books were reviewed everywhere,” the author told Smith, “and then people stopped reviewing me.” Swift’s former Doubleday editor told Smith, “At first Edward was trying to please himself, but also work within the conventions of the New York literary world, and then I think he stopped being concerned about that.” His work came to be considered too “unusual … too fanciful” for the tastes of New York marketing departments, Swift told Smith. To those readers acquainted with the writer’s Big Thicket roots, it seems unlikely that Swift’s outlook could have grown more peculiar. Rather than becoming progressively weirder, Swift was simply coming closer to home-his warped, Gothic torch for East Texas burning ever more brightly.

Long before I made that benighted trip to Woodville-in fact, just after I first finished poring through his books-I resolved to meet Swift. I telephoned his publisher, who gave me an e-mail address, and later that day I managed to reach the author in New York City, his home of more than 30 years, just as he was boxing up his life to move to Mexico. “Mr. Swift,” I told him, “I’d like to meet you. Someday, I’d like to write something about you and your books. They’ve meant so much to me.”

“You must have read Splendora,” he said, offhandedly, as though I were being awfully boring.

“Oh, Mr. Swift,” I answered. “I’ve read all your books.”

“You have?” he asked.

Two days later, I visited his Manhattan apartment near 18th and 8th-a tiny, eccentric cave for a giant, eccentric man. He was enormously tall and thin, with an Indian nose, and very thick, very white hair pulled into a ponytail. Dressed all in black, Swift looked New York, but his voice was East Texas in a way that almost doesn’t exist anymore. As he told one harrowingly funny story after the next, he’d rush his words quickly, then halt suddenly, with terrific drama. One story recounted his mother’s veiled attempts to explain that one of Edward’s childhood playmates was a hermaphrodite: “Eddie,” she said, with raised eyebrow and great significance, “so-and-so neither shops in the ladies’ nor the gentlemen’s department.” Another involved a friend from Dallas who killed herself on Oscar night: “I just don’t care who wins anymore!” were her final, despairing words. Yet another included a delightful impression of Maxine Mesinger, the late Houston gossip columnist and a friend of Swift’s, purring into the telephone: “One moment, darrllingg, I’m on the other line with O-liv-i-a-de-Hav-i-lland.”

I spent the evening beguiled by Swift, as charmed by his conversation as I’d been by his writing. We talked about our great and mixed love for Texas, of our mothers and our writing. When I described to him my struggles with my book, he became serious, offering encouraging stories of his own pitfalls and triumphs.

Just before leaving, I asked him to autograph c

pies of his books I’d brought with me. After he signed them, he did a lovely thing. In a long-past, gentler day, certain New York publishers presented authors with a single, leather-bound copy of their books as mementos commemorating its publication. That evening in his dismantled apartment, Swift asked me to wait while he rummaged through a series of half-packed cardboard boxes and retrieved the single, shopworn, Morocco-bound copy of Splendora Viking had given him in 1978. Then he signed the book For Robert and stuck it, along with the others, into my book bag.

I’m surely not the first to point out that the Texas canon, as currently compiled, greatly privileges the Southwestern over the Southern, the masculine over the feminine, or that machismo is prized in Austin literary circles even more highly than those of New York or L.A. So it isn’t surprising that Swift’s Lone Star fabulousness has failed to find footing in a climate where John Graves (God bless him) sets the standard. It is nevertheless a sad predicament in which Swift has found himself-too truly, startlingly Texan for New York City, too fey for Texas. Isn’t it strange? In such a large state, you’d think there’d be more room. As for Edward Swift, he’s gone and moved to Mexico.

Robert Leleux, author of The Memoirs of a Beautiful Boy, lives in New York but misses Houston.