The Skins They Carried

Military tattoos in the age of Iraq

The American Illustrators tattoo shop in Killeen is one of more than a dozen parlors that line the streets of this flat, sprawling town. Inside, a techno beat thunders through the wall from the club next door as artist Toby Fry traces a drop of blood with dark black wings on the back of Army medic Clint McCullough. The tattoo will take hours to complete, so McCullough chats over the sound of the buzzing machine and the sting of the needles.

“This year I was hit by six IEDs,” McCullough says. “I got three concussions, and now I’ve been getting chronic headaches and back pain. So they gave me an MRI, and they’re seeing spots on my brain. They’re worried about brain damage. But everyone who knows me for five minutes knows I have brain damage, and it’s not from an IED.”

“Like everyone here,” Fry adds with a laugh.

As Fry fills in the tattoo, McCullough talks about his year in Iraq: the challenges of treating the wounded on the battlefield, the slow progress of the Iraqi army toward self-sufficiency, the stress of leaving his wife back home. Fry has learned to be a listener and confidant, a sort of therapist with a needle gun. He came here from New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and when he saw how much money he could make tattooing soldiers, he decided to stay. But he says nothing prepared him to tattoo soldiers heading off to Iraq, or those returning with the scars of war. “You do a tattoo, and they come back, and it’s partially missing,” he says. “Everyone feels a little bit of it.”

It’s an emotionally draining job. Soldiers go to Killeen’s bars to forget, but they come to the tattoo shops to remember. The images they put on their skin are diaries they’ll take to the grave, marking the fear and bravado of war, the faith to make it through, and the losses they carry inside. “Tattoos are a way to solidify emotions,” Fry says. “So I try to just shut up and listen to what they have to say. It’s just part of it. I think people find it comforting to talk to a stranger who is doing something as intimate as piercing your skin.”

There are four basic types of military tattoos, and Fry says he can almost always tell whether a soldier is a fresh recruit or a veteran by the type he choose. Soldiers headed off to war tend to favor vintage, gung-ho Americana, a style perfected during the World War II era by Sailor Jerry, a Honolulu-based tattoo artist whose stock images of eagles, weapons, and pinup girls evoke a more innocent, patriotic era. Pvt. Thomas Hair, who has a billowing, three-masted ship sailing across his forearm, has modified the message. “It used to have a scroll underneath that said ‘homeward,'” he says, “but I changed it to ‘wayward.’ I’m definitely not homeward. I’ve got a few years left.”

Hair flashes a thin smile. He knows he’ll soon be called up to Iraq. He says he plans to have his arm covered with Sailor Jerry tattoos before he leaves, and he’s already picked out a swaying hula girl to go with the ship. He thinks the vintage tattoos connect him to American soldiers who went off to fight in Europe with the same images on their skin. “It’s a way to make me into a normal person,” he says. “I can be me, instead of Private Hair. I’m not just another guy in a uniform. I can stand out.”

That’s a sentiment you hear a lot from tattooed soldiers, and commanding officers aren’t happy about it. Hair was turned down by the Marines because of a spiderweb tattoo on his elbow, so he joined the Army, which tolerates non-offensive tattoos. But Hair is determined to push the envelope. “One soldier got a tattoo on his neck,” Hair says, “and the captain was staring at it with an angry look on his face. I don’t think he likes neck tattoos, so I’m going to get one. All I can do is piss him off. I can’t do anything else to him.”

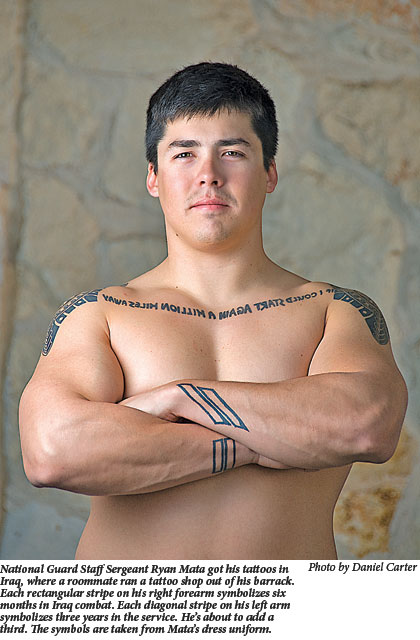

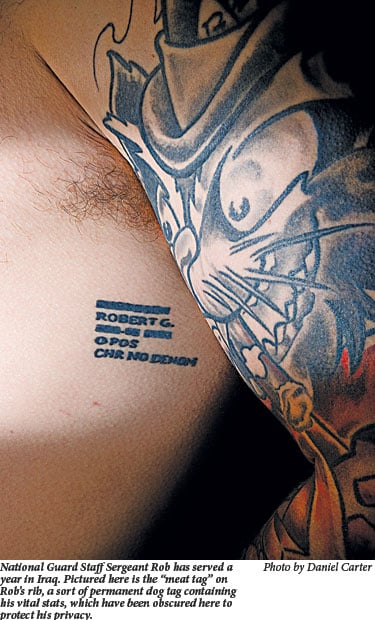

The second type of military tattoo is for soldiers who want to make their uniform permanent. Some do this for practical reasons, tattooing dog tags complete with military ID and Social Security numbers onto their torsos in case they become separated from their heads during combat. These tattoos, called “meat tags,” can be elaborate: One Killeen variation shows the dog tags in an open wound, wrapped around an exposed rib.

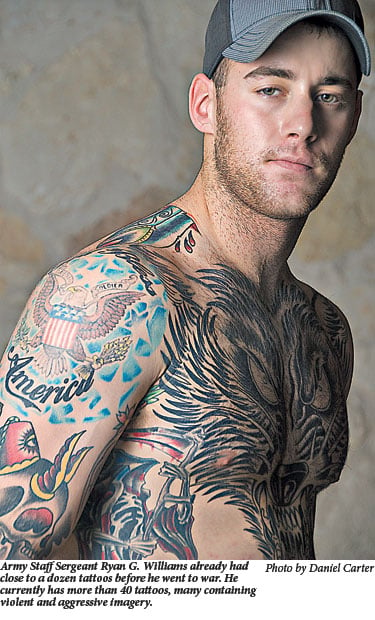

Many soldiers tattoo symbols of their platoon, rank, or specialty on their body out of pride or bravado. It’s a way of branding themselves soldiers even after the uniform comes off. Sgt. Ryan Williams’ job is to call in artillery fire on the enemy, and the job’s symbol is a hand clutching lightning bolts. “I wanted to make mine unique,” he says, “so I have it chopped off with a bone sticking out, because I like that gory stuff. And I had the word ‘fist’ tattooed on the knuckles, and made the fist blue, so it looks like it’s rotting.”

Williams’ entire chest and both arms are covered with ink, and the tattoos are arranged to symbolize the duality of his nature. “I get pretty crazy when I drink,” Williams says. “They call me Mr. Hyde.” On one side of his ribcage is a grim reaper figure draped in an American flag. On the other side is the Virgin Mary.

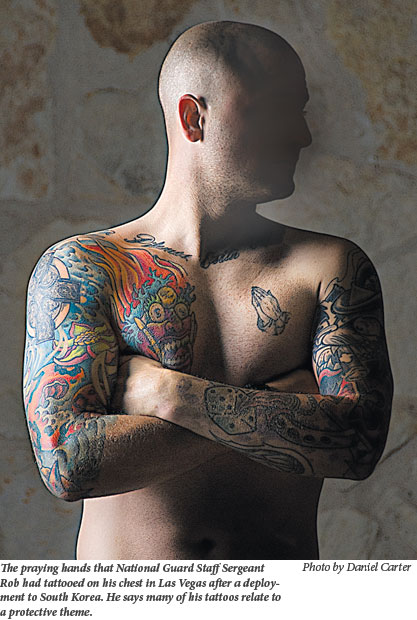

Religious iconography constitutes a third category of military tattoo. Spc. Daniel Lee spends a lot of the money he makes in Iraq at a Killeen shop called Kingpin Tattoos. He’s got the tattoos he shows the world, his arms covered with images of fortune cookies and Chinese takeout boxes, a humorous celebration of his Chinese-American heritage. But Lee has private tattoos as well. Before he was called up the first time, he got an image of hands clasped in prayer tattooed on one side of his chest, and a portrait of Jesus, complete with crown of thorns, on the other. “The feeling just hit that I was going to Iraq,” Lee remembers. “And I wanted to keep my faith somewhere. Some people carry a Bible into war, but I wanted something more permanent. I like keeping my faith right on my body, where I can see it every time I take a shower. It makes me feel better to have a more permanent reminder.”

Not everyone feels that way. Outside of Kingpin Tattoos, a blond soldier named Mac McConnell sits on a bench and smokes a cigarette. He’s got an upside-down cross tattooed across his bicep, his reaction to being force-fed religion in the Army. “The only time we get a break during basic training is to get to go to church,” he says. “And that pisses me off, since I’m not religious. If people can’t figure out right and wrong for themselves, they’re pathetic. It’s a way of not thinking.”

A fourth type of military tattoo stands as a reminder of the human cost of the Iraq war. All the tattoo shops in Killeen now do dozens of memorial tattoos each month; the most common is the iconic image of boots, machine gun, and Kevlar helmet. Memorial tattoos honor friends and comrades who’ve died in war-though not always by enemy fire. William Flood is a 20-year-old interrogator just back from Iraq with a memorial tattoo on his ankle. He says it’s dedicated to two close friends, Wesley and Alfredo, neither of whom died in combat. “Wesley was nice and quiet most of the time,” Flood says. “But he could get wild and have a good time. Then one day over there, he committed suicide without warning. I have no idea why. He wasn’t showing any signs. It pissed me off because I wasn’t expecting it. And then other soldiers started joking about it, which made me even more upset.”

Flood was still reeling from Wesley’s death when he heard another of his closest friends had been killed on R&R, in a car crash. “It just seemed so hard to believe,” he says. “It didn’t even hit me until I got back.” One of the first things he did when he returned was go to the tattoo shop and bring that pain to the surface.

Others have lists of the dead on their bodies. As Artist Toby Fry finishes Army medic Clint McCullough’s tattoo, the shop has closed, and everyone else has left. Fry fills in the dark wings, and the drop of blood, and above it he writes the name of McCullough’s unit, “Blood Angels.” Below that, he writes the names of three of McCullough’s fellow medics who died in Iraq: Dan, Frank, and John. “The world is at a huge loss because Dan’s not with us anymore,” McCullough says, getting visibly choked up. “He was an amazing person, an awesome friend, and one of the greatest medics I’ve ever met. He almost made his 26th birthday.”

The tattoo takes a couple hours to complete, giving McCullough time to talk about each of the guys on his back-how they lived and how they died. He says the memorial tattoo is a way to keep the memory of his fallen friends alive. “You carry a lot of baggage as a soldier,” he says. “Losing guys like that. So I just decided to do something external the rest of the world can see.”

Michael May is a writer and public radio reporter living in Austin.