Home Again

One time, I had a friend who was dying of ovarian cancer. When she’d done all she could with traditional medicine, she turned to holistic and Eastern healing, and it helped her. I drove her to energy healing once, in Austin, and as the practitioner’s long, white hands hovered over my friend’s tortured belly, I felt such goodness emanating from them that I left feeling light, and my friend did too-free of pain.

After that day, I watched the other things she did. She meditated; she gave thanks. I gave thanks. Too lazy to meditate. My friend died and left a good hunk of Austin drunk and bereft. We gathered on a sunny afternoon in a backyard under oak trees, and somebody set up a microphone and amps. We drug out guitars and raised a mighty clatter for our friend. We told death that we were still playing, still dancing, still alive, and that our passionate survival would be our friend’s continuance. We mourned in this way, and when the party disbanded, I boarded a plane back to New York.

I didn’t think, at that time, that I would come home-ever. Home was not verdant, hip Austin. Home was Pearland, Texas, a little eddy that formed as traffic flowed away from Houston on state Highway 288. Pearland has a body shop with a marquee that reads, “Paint Your Camaro Here.” It has little beauty shops and flower shops, a Dairy Queen and a Wal-Mart, and every other structure is either a church or a Mexican restaurant. Pearland has fields with cattle grazing behind rusted barbed wire. It has one main street, which is called Main Street.

Train tracks divide east from west. The west side is poorer and always floods. Most of the people there own those flooding houses, and after each heavy rain they tear soggy carpet up, nails and all, and drag it out into the yard. West has the VFW hall with the cannon out front and bingo nights. On the west side, there are clotheslines in the backyards and kid’s toys stuck in the mud in the front.

The east side has most of the businesses, banks, City Hall, the park, and the pool. It also has Green Tee, the fancy neighborhood where you can only go 30 mph and the cops are quick to ticket. Built around a golf course and a country club, Green Tee is crowded with fat, brick houses with enormous garages and no porches, houses with tiny, perfect lawns on which children never play. At Christmas, the homeowner’s association holds a contest for the best yard decorations. The resulting Technicolor, motorized, deer-and-Jesus-tacular brings the church youth groups out in the backs of trucks filled with itchy hay. They lurch through the drawling traffic to gawk at the show.

I came back to Pearland not to reclaim my roots, but because I didn’t have a choice. I’d lost my money and mind in New York. Being home didn’t help. Everywhere I looked was a memory I’d long ago put down like a sick dog, and here they were, alive and waiting for me, panting in my face. There were so many that I couldn’t avoid them. I responded with some mature drunken hermitry. But on some drunk, hermited afternoon, maybe a month after I got home, I remembered my friend who had died. Specifically, I remembered something she’d done.

One of her holistic healers had told her that everywhere she’d had an experience that marked her soul, good or bad, she’d left some of her chi. Her healer said that her chi, or life force, would linger there, and that my friend could go back to those places, like the corner where she’d had her motorcycle accident, and collect her chi for strength toward her healing.

Now you could say that this was the same as a therapist talking someone through the traumatic memory to help them get over it, and maybe it was. But calling it “reclaiming chi” jibed more with what I experienced when I drove past such places-a sense that the person I was then was still there, waiting for something to be remembered or resolved.

I can do that, I thought. I have nothing better to do.

I went to the high school. Backstage in the auditorium, I remembered every show I’d been in, watching for my entrance from the wings. I remembered kids dressed in black who pulled the curtains and never went onstage except to move sets. The dark, silent backstage vibrated with memory. It smelled like sawdust and paint and floor wax. How I’d sweated with fear on those scuffed wood floors, alert like a deer, praying nothing went wrong. We seemed so old and competent then. The seats were filled by people who, to us, belonged in the audience, people who shifted their weight and looked over the program. We were so much more alive than they, I’d thought. I had not set foot on a stage since leaving high school. I had forgotten that part. Pearland had come out in droves for the school musicals. They’d sold out the theaters. I’d remembered Pearland as a cultural backwater, but it came back to me. They’d paid $7.50 a ticket. They’d given standing ovations.

I went to the church where my mother played the organ for 22 years-and still does. The sanctuary was quiet, the carpet still green, the wooden pews still held red Bibles. The metal cross hung suspended from the ceiling, larger than a man would have ever been. Behind it, a skylight. Behind that, the back brick wall with the stained-glass Jesus in his white robe, arms outstretched. I used to study that face every Sunday morning, not listening to the service. To me, it was not an iconic piece of art, but a representation of the actual Jesus. I treated it like a photograph. This was Him, I tried to know. This was God made flesh. He just looked like a man. When I was young, this place was a true sanctuary. Everyone in the choir knew me, and my mother and father and sister. I’d knelt on the green cushions that lined the altar and put a tiny square of bread in my mouth and moved it around with my tongue, thinking “This, this, is the body of Christ.” I’d drunk Welch’s grape juice from a thimble-sized plastic cup and thought, “This is his red flowing blood.” I had asked for forgiveness for sins I couldn’t name and heard the preacher say, “All fall short of the glory of God.” I’d wondered why. Why couldn’t we be perfect, if we were careful enough? Why were we doomed to fail?

In the 10 years since I had been there, I had stopped trying. I’d given up the game I couldn’t win. I knelt at the altar and didn’t ask for forgiveness, didn’t try to understand anything. I just stayed there, hands folded, the lofted ceiling lit only by the skylight, and considered that who I was then and who I am now were the same. I was afraid, being there, that God would spot me again and scan my brain and tally up my iniquities. But I trusted Him enough to let him. It turned out I still believed at least that much.

That night, I drove around alone. This was what I loved best in my hometown, back when I lived here. I would go out after dark in my cherry-red 1986 Pontiac Sunbird with the “Kill Your Television” sticker on the back and go to my friend’s houses and pick them up. We would drive and listen to music, not speaking. It was enough to be on our own, to be free to turn or not turn, to stop or not stop. We were stretching our legs. We were becoming at home in the world. We didn’t mind, then, that there were only strip malls and Mexican restaurants and churches around. We didn’t think there was anything special about the malls being interrupted by wide fields where cattle grazed, some craning their necks through the barbed wire to get at the sweet grass on the road’s shoulder. We’d never been somewhere where crickets and frogs didn’t chirp in the night, where the stars weren’t visible, where the sky didn’t reach from one edge of our peripheral vision to the other. We didn’t know, then, what we had. We couldn’t know unless we left and came back.

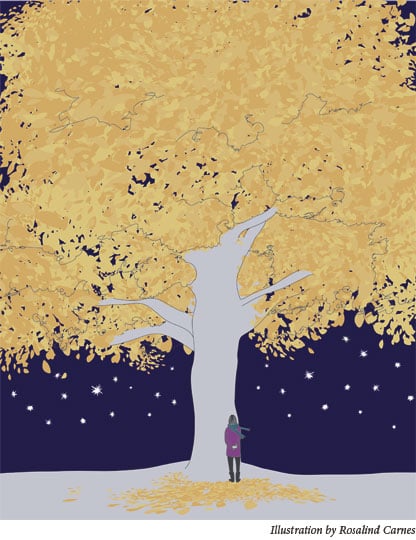

I drove to the park, past the house where I grew up, where I lived when my parents were still married. I drove to the dark park, around the half-mile loop with the picnic tables, past a car where a couple was no doubt necking or breaking up. I went three-fourths of the way around and stopped in front of my tree.

This tree was where I’d gone when things went very right or very wrong. I’d checked in with it silently. As long as it was still there, and I was still there, we were OK. It had grown quite a lot, but its arms still reached out and up, and its leaves turned up, round, toward the sky. It had stayed. I had not wanted to know Pearland again, admit that I was back, admit how strange and straying and disappointing life had been since I left. I had meant to keep moving and not look over my shoulder. But the church and the high school and the tree were still there. They were still mine, and I was still myself. I collected the memories and hugged them close. I would not hide anymore: I was home.

Emily DePrang is a writer from Pearland, Texas.