The Miracle Worker

The Miracle Worker

BY LEE MIDDLETON

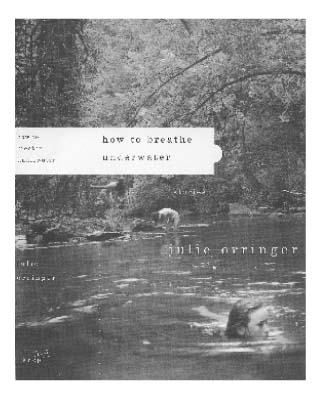

How to Breathe Underwater: Stories By Julie Orringer Knopf 240 pages, $21

ne of the things that I resist in fiction is the idea that a terrible experience will lead to some kind of epiphany or positive change in a character,” Julie Orringer said in a recent interview with Robert Birnbaum of the Dallas Morning News. Orringer, a 30-year-old alumna of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, practices what she preaches in her much praised first book, How to Breathe Underwater. In nine stories examining responses to pain and loss, this collection’s moral, if it has one, is that pain may not make us better people, but it shapes and twists us, and makes us who we are. The stories are those of girls and young women facing “terrible experiences”—mothers who are dying, children who see other children die—people living on the fault lines of tragedy, captured precisely at the moment when the earth has opened up to swallow them. Does this sound a bit extreme? Well it is. The miracle of this book is that Orringer actually pulls it off.

ne of the things that I resist in fiction is the idea that a terrible experience will lead to some kind of epiphany or positive change in a character,” Julie Orringer said in a recent interview with Robert Birnbaum of the Dallas Morning News. Orringer, a 30-year-old alumna of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, practices what she preaches in her much praised first book, How to Breathe Underwater. In nine stories examining responses to pain and loss, this collection’s moral, if it has one, is that pain may not make us better people, but it shapes and twists us, and makes us who we are. The stories are those of girls and young women facing “terrible experiences”—mothers who are dying, children who see other children die—people living on the fault lines of tragedy, captured precisely at the moment when the earth has opened up to swallow them. Does this sound a bit extreme? Well it is. The miracle of this book is that Orringer actually pulls it off.

Reading these stories, my schmaltz radar set on high, I sometimes questioned the scenarios Orringer had created for her female protagonists. Evoking the delicate cruelties of adolescence, they are constantly on the edge of behaving in manners too extreme, involved in situations that are too dramatic. But Orringer focuses on the quiet anguish of characters who get by rather than cashing in on the potential sensationalism of heroics or redemption, thus ensuring that these tales never lapse into melodrama. Her protagonists react to their circumstances with an understatement and moral imperfection that sometimes made me catch my breath. I was hooked by every story because I cared about its characters, and the high dramatic stakes that I might have questioned in a story’s beginning only pulled me in more deeply by its end.

Among the themes that recur throughout the collection is the inability to rise to the demands of one’s better self. With tight control over the subtle and fluid nature of human smallness, Orringer builds a sense of danger into her evocation of our more vicious impulses and their unintended and sometimes horrifying consequences. In the first story, “Pilgrims,” Ella and Ben are taken by their parents to a New Age Thanksgiving dinner composed of families brought together by the blight of cancer. Ella and Ben are forced to play with the other children who seem to Ella like some escaped tribe from The Lord of the Flies. Callous violence on the part of one of the boys leads to a shocking finale in which all the children are made complicit. Ella and Ben go home, their distress undetected by parents too preoccupied by the doom surrounding them to perceive their children’s need.

In “Care” we meet Tessa, a 20-something pill addict who reflects on her mother’s early death and her emotional abandonment by her older sister while she babysits her sister’s daughter. The story begins:

Tessa knows how to cross the street with a six-year-old: You take her hand, look both ways, and wait until it’s safe… There’s a right way to take care of a child, she knows, and a wrong way. Many wrong ways. What you do not do: Take the drugs that are in your pocket, the Devvies and the Sallies in their silver pillbox.

With a light touch, Orringer brilliantly captures the way Tessa perpetuates her personal sorrow by trying to take others down with her. In “Stations of the Cross,” Lila is the Jewish kid new to a small Louisiana town, painfully aware of her social dependence on her popular friend, Carney. The story takes place on the day of Carney’s first communion, to which Dale, Carney’s half-black, “actual dictionary-definition bastard” cousin, comes. Wanting someone to pay for the social humiliation of Dale’s presence, Carney creates an alliance of fear with Lila, making the Jewish girl an accomplice to a horrific racist tantrum.

Finely tuned to the subtle power dynamics between young girls, many of these stories hinge on the pernicious hierarchies of emerging sexuality. “Stars of Motown Shining Bright” and “The Smoothest Way Is Full of Stones” both pair teenaged girls bound by relationships that are a strange combination of jealousy and the need to have someone else to look at in order to define oneself. In “When She Is Old and I Am Famous” (one of my favorites), dumpy Mira the artist is forced to host her cousin, Aïda the Prada model, for a weekend in Florence where Mira is studying painting. Mira fights back her jealousy as she watches her photographer friend Joseph snapping photos of Aïda, observing that “he looks as if he would like to throw a net over her.” Later, following a minor debacle instigated by Aïda’s carelessness, Mira and her ethereally beautiful cousin sit together in a café, strangely reconciled, discussing the future. In a rare moment of honesty, Aïda reveals a surprising awareness of the empty and transitory nature of her career, causing Mira to muse, “I wonder if she will survive what will happen to her… There are many things I would ask her if only we liked each other better.”

Finely tuned to the subtle power dynamics between young girls, many of these stories hinge on the pernicious hierarchies of emerging sexuality. “Stars of Motown Shining Bright” and “The Smoothest Way Is Full of Stones” both pair teenaged girls bound by relationships that are a strange combination of jealousy and the need to have someone else to look at in order to define oneself. In “When She Is Old and I Am Famous” (one of my favorites), dumpy Mira the artist is forced to host her cousin, Aïda the Prada model, for a weekend in Florence where Mira is studying painting. Mira fights back her jealousy as she watches her photographer friend Joseph snapping photos of Aïda, observing that “he looks as if he would like to throw a net over her.” Later, following a minor debacle instigated by Aïda’s carelessness, Mira and her ethereally beautiful cousin sit together in a café, strangely reconciled, discussing the future. In a rare moment of honesty, Aïda reveals a surprising awareness of the empty and transitory nature of her career, causing Mira to muse, “I wonder if she will survive what will happen to her… There are many things I would ask her if only we liked each other better.”

Each story in the collection demonstrates an acute understanding of the isolation and loneliness integral to change. “Note to Sixth-Grade Self” is another favorite, written in the form of adult advice to one’s awkward, alienated younger self. After being chosen to dance with the popular Eric Cassio for a dance class demonstration, the narrator’s presumably geeky sixth-grade self is punished—tripped and injured during field hockey practice—by the girls whose social status is offended by that “threat to the social order.” The older narrator advises,

That night, in the bath, replay in your head the final moment of your dance with Eric Cassio. Ignore the fact that he would not look at you that day. Relish the sting of bathwater on your cuts. Tell yourself that the moment with Eric was worth it. Twenty years later, you will still think so.

The fact that ultimately we must deal with change and suffering alone is reiterated in “What We Save,” a story in which 14-year-old Helena visits Disney World with her sister and her mother. Helena’s mother is dying of cancer and has arranged to meet her high school boyfriend and his family at the magic kingdom that day. Trying to understand why her mother would need to do this, Helena confronts the reality of her mother as a person with layered existences, some of which are independent of her daughters, and all of which will soon be extinguished.

Helena imagined that if she glanced behind her, she might see a trail of things her mother had let fall: bits of iridescent fabric and glass, white petals, locks of hair. She seemed truer to herself, finished with trying to make things appear different from the way they were.

In what is ostensibly the collection’s title story, another young girl grapples with death and sorrow’s alienating truths. “The Isabel Fish” is narrated from the point of view of 14-year-old Maddy who has recently survived a car accident in which her friend, Isabel, drowned. Attempting to recover from the trauma of the accident and the guilt of surviving, Maddy tries to overcome her fear of water by taking scuba lessons where she will learn how to breathe underwater.

Finely crafted and often deeply sad at their core, the nine stories that make up How to Breathe Underwater do the thing that good fiction always should—that is, to reproduce some of the uglier and simultaneously all-too-common responses to living in a world that doesn’t care if we need a break. These stories provide a fictional space where we as readers can contemplate why people sometimes crumble and do the wrong thing. Orringer observes her characters’ failures and pain with neither judgment nor pity, and somehow writes these unsentimental tragedies in a way that lets the reader emerge, like Ella in “Pilgrims,” with an awareness that, for better or worse, change will come:

She closed her eyes and followed the car in her mind down the streets that led to their house, until it seemed they had driven past their house long ago and were moving on to a place where strange beds awaited them, where they would fall asleep thinking of dark forests and wake to the lives of strangers.

Lee Middleton is a fiction writer in the University of Texas’ Creative Writing Program.