The Long Road Home

Prosecutions, mass graves and the police archive provide clues in the deaths of thousands of Guatemalans.

A version of this story ran in the April 2012 issue.

On December 19, 1980, the last day she was seen alive, Alaide Foppa left her mother’s house in Guatemala City on her way to the airport.

At 66, Foppa was an internationally known leftist poet and feminist. When the CIA-backed Guatemalan military overthrew the country’s elected government in 1954, Foppa had moved her family to Mexico. From there, she watched as Guatemala’s new military leaders quickly moved against their opponents. They rolled back a decade of democratic reforms. They banned trade unions and left-wing political parties. And as their control over the country tightened, their critics began to disappear.

Foppa was a very visible part of a group of Guatemalan intellectuals who denounced human rights violations in their country. By the 1960s, her name began appearing on the regular lists of “known subversives” published by Guatemalan anti-communist organizations. People on the lists often ended up dead.

That December she had returned to Guatemala City to visit her ailing mother. When the visit ended, her mother’s driver took Foppa to the airport for her flight back to Mexico.

She never made it. Julio Solórzano Foppa, her eldest son, was living in Mexico City then. That afternoon he got a call from his grandmother. There was panic in her voice. The car and driver hadn’t made it back to her home. Had he heard from Alaide?

When he got that call, Solórzano said later, he knew he would never see his mother again.

Foppa was never found. There was never a body. There was never a certificate of death. Foppa, the car, and the driver vanished as though they had never been.

The most chilling thing about Foppa’s disappearance is how ordinary it was. In those days in Guatemala, as in other right-wing dictatorships, people simply vanished. Some, like Foppa, were well-known intellectuals. Some were labor leaders, journalists, leftist activists. Some were just unlucky, mistaken for someone else.

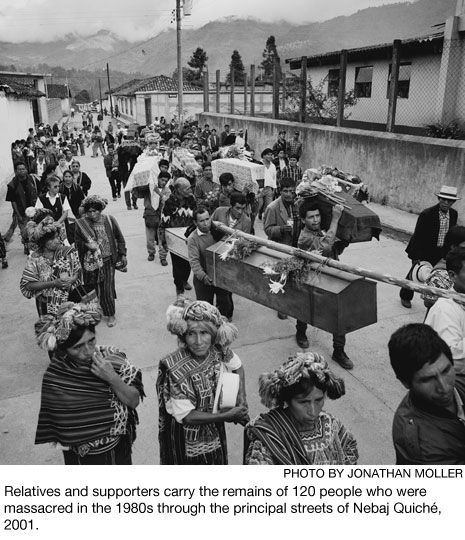

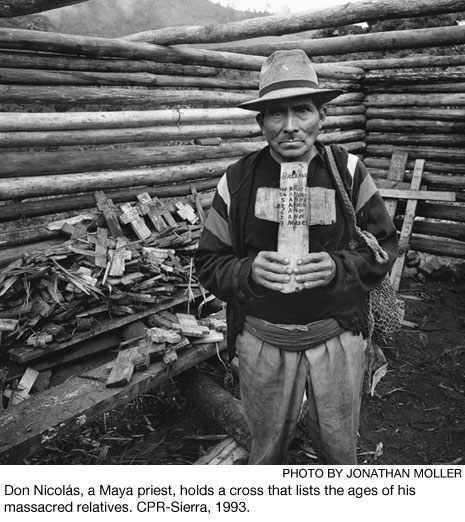

During the 36-year Guatemalan civil war, the military regime killed over 200,000 people. The vast majority were Mayans from rural areas. Some 45,000 people, including Foppa, were disappeared, mostly in and around Guatemala City. Consider that the national population is only 8 million, and you start to get a sense of the scale of this trauma.

When the war ended in 1996, a loose umbrella of human rights and victims rights groups began to organize. They demanded justice for their dead, who were slowly being discovered in mass graves. But the military, along with the police, had spent a lot of time trying to bury the truth. For the last three decades, Guatemalans like Solórzano have been trying to literally dig it up. Between the upcoming trials of former military leaders, forensic evidence from mass graves and the 80 million documents about police activities at the National Police Archive, the families of Guatemala’s missing and dead hope the truth will finally emerge.

On November 13, 1960, six years after the coup, a group of left-wing junior officers from the national military academy revolted against the ruling junta. Their revolt failed, and the survivors hid in the hills, establishing a Marxist guerilla movement, the Movimiento Revolucionario 13 Noviembre, or MR-13. This began a civil war in which most of the victims were civilians killed by one or another of the military governments in power during those years.

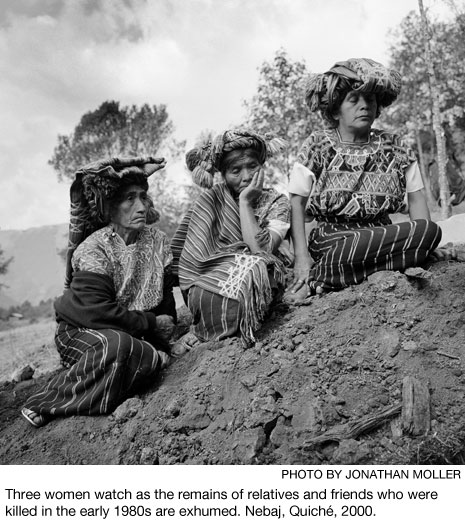

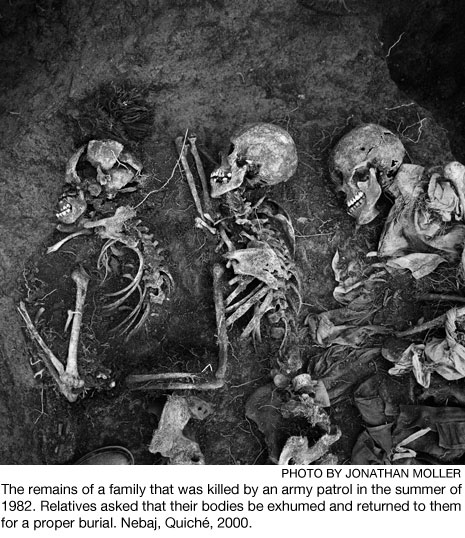

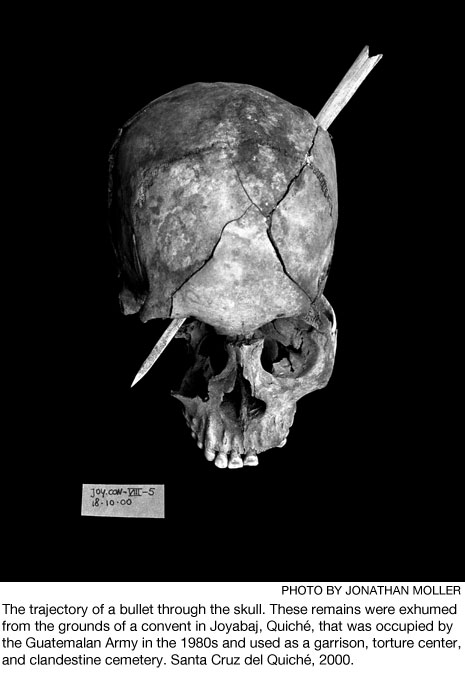

These killings and disappearances happened largely in secret. Entire villages disappeared, their inhabitants shot or burned and buried in mass graves. The army depopulated huge swaths of the Guatemalan highlands. In urban areas, the military kidnapped dissidents off the streets in broad daylight.

Even today, there is no complete list of names of everyone the military and police killed. Army officials from that period, to this day, deny there were massacres. If there were, one has argued, they were the fault of “rogue officers” or “the guerillas.”

Solórzano, though, was in a unique position to find answers about his mother’s disappearance. Julio Solórzano grew up as expatriate royalty in Mexico, where his parents were leading lights of the Guatemalan community that fled there after the 1954 coup. His father was Juan Jose Arevalo, the former president who led the 1944 “October Revolution” that overthrew the military and established Guatemala’s brief democratic spring. His stepfather, Mario Solórzano, was a cabinet advisor to the next president, Jacobo Arbenz Guzman, when he was overthrown in the CIA-backed military coup in 1954.

The day after Foppa’s disappearance, Solórzano and his sister threw all their resources into finding her. They knew that if their mother was still alive, it would likely be for only hours or days more.

But it was December 20, the start of the Christmas holidays. Across the world, government and human rights offices were closed. By the time they were able to arrange meetings, they had lost days. Solórzano’s sister flew to New York to talk to the UN Commission on Human Rights. Solórzano flew to Paris, where he watched Julio Cortázar, the famous Argentine writer, give a heartfelt speech to the French Senate asking lawmakers to help find Foppa. Human rights representatives at the UN and the Organization of American States made inquiries.

In Mexico, Solórzano met with Jorge Castañeda y Álvarez de la Rosa, the Mexican Chancellor, a position analogous to the U.S. Secretary of State. On Castañeda’s advice, Mexican President Jose Lopez Portillo formed a commission, including Solórzano, leading legal scholars and a prominent newspaper publisher, to fly to Guatemala and investigate Foppa’s disappearance. President Portillo gave them his private plane.

They were ready to go when the chancellor summoned Solórzano. He had just received a Telex from the Guatemalan military government, to whom the Mexicans had explained their mission.

“They said, ‘We, too, are very worried about the whereabouts of Doctora Alaide Foppa,’” Solórzano recalled when I met him at his office in Guatemala City. “‘We too are trying everything to find her, and we welcome the commission you’ve named. But we think that it is our duty to warn you that international communism, in its efforts to make the Guatemalan government look bad, may cause harm … to come to them.’”

He grimaced. “It was a clear threat, and we all took it as such. You have to remember that less than a year before, a bunch of indigenious activists had occupied the Spanish embassy in Guatemala City. The army burned it down with them inside. So they didn’t really have a whole lot of respect for international law.”

The rest of the commission, Solórzano said, was waiting in the next room. The chancellor looked at Solórzano. “What do you think?”

Solórzano said, “Well, we know the Guatemalan government has been behind all the repression. We know they’re probably behind this disappearance.” If there was any reason to think Foppa was alive, he said, he would fly to Guatemala with the commission and take his chances trying to find her.

The commission was willing, the chancellor told him. They would fly on his decision.

“It was a very hard decision,” Solórzano told me. “But in the end I said no. I said, ‘We have no evidence she’s alive. We have no excuse to risk these people’s lives.’”

He paused. “With very few [exceptions] the disappeared never reappeared in Guatemala.”

The commission dissolved. Solórzano’s brother, eventually, heard something about their mother. Three of Solórzano’s siblings had gone back to Guatemala to join the Marxist guerillas fighting the regime. Two or three months after Foppa’s disappearance, Solórzano’s younger brother Mario called him in Mexico. He said the guerillas had received a report that Foppa had been tortured and killed the day of her capture by a death squad run by a high-ranking Guatemalan minister. Mario and another brother later died in the Guatemala mountains. The report was never confirmed.

When the military handed power to Guatemala’s new civilian government in 1996, it did so under the express understanding that soldiers and officers were never going to be held accountable for what they had done during the war. For almost the entire period since the end of the civil war, the dictator-generals who ran the military have maintained prominent roles in public life. Until January of this year—when he was indicted by a Guatemalan court on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity—Efraín Rios Montt, who ran the government during some of Guatemala’s worst years, served in the country’s Congress.

His indictment is largely due to the efforts of a network of international and Guatemalan human rights groups created when the civil war ended. From the beginning of the post-war period, there had been a split between the old military regime and the human rights organizations. The surviving members of the regime viewed the growing human rights investigations into the war and attempts to identify the dead with growing unease. They fought the investigations by refusing to help and, occasionally, with murder. In 1998, Bishop Juan Jose Gerardi, a driving force behind the Recovery of Historical Memory, a project to provide a record of war atrocities, was bludgeoned to death in his garage in Guatemala City. Three military officers were convicted of his murder and sentenced to 30-year terms.

A key part of the military leaders’ defense was that there was no proof of what they had done. There were no records.

But, human rights workers say, the thing about totalitarian governments is that there are always records.

“When I came here in the ’90s,” Marcie Mersky, a human rights worker with the New York-based International Center for Transitional Justice, told me, “it was right after the war. We went to go request files from the police. They said, ‘Sorry, we destroyed them.’

“It was bullshit. No repressive bureaucracy ever destroys documents. Ever. They can’t do it. If they say they’ve destroyed them, they’re lying. They may be hidden, but they’re around.”

There is no better symbol of this principle than the National Police Archive. In 2005, an explosion at a police station in a rough neighborhood on the outskirts of Guatemala City revealed a giant store of hidden records. Firemen rushing in found piles of documents—records of the National Police, dating back to its founding in 1880.

In a country where the actions of the police had always been carried out in deepest secrecy, the discovery was a big deal.

The archive is now located in a corner of a police station, part of a sprawling compound that houses the headquarters of the Sixth Corps of the Guatemalan National Police. During the war, the Sixth Corps was notorious for repression, and the base saw a lot of traffic. There are persistent rumors, possibly groundless but endlessly repeated, that bodies of the disappeared lay beneath its floors.

I went to the archive on a gray and rainy day in October. My cab pulled up to the guard station outside the archive. Past the gate were rows of featureless concrete buildings. Unsmiling National Police troops with submachine guns opened the gate and waved us into a muddy parking lot surrounded by a low concrete wall decorated with murals.

I got out. The cab drove away. In the distance I heard gunshots from a police firing range. A Guatemalan in a raincoat walked up to me. “Who are you?” he asked.

I told him. “Oh,” he said. “You want Gustavo.”

Gustavo Meaño Brenner was a large man with glasses. He was the national coordinator for the Police Archive. He was sitting in a waiting room with a Guatemalan journalist and her family; she had dragged them out of bed on a Saturday morning to come look at documents.

“Well,” Brenner said, “let’s go.” He led us around the building. We came to an iron door to a 30-foot-tall concrete warehouse. Brenner opened it.

We stepped through. Behind me, one of the Guatemalans swore softly. We were standing in a cavernous room 100 yards deep. The wall was punctuated with alcoves that could have once been cells.

Instead of people they held paper. All around us, filling every corner of the room, were great untidy dunes of documents 10 feet high. Some were in marked boxes or folders: “Homicides, 1947-1948.” Others were tied in loose bundles, or simply loose. The air smelled of mildew and wet paper. The only sounds were the dull hum of the air conditioner and the distant, persistent gunshots from the firing range.

When the archive was discovered, the Guatemalan Public Ministry—the equivalent of an attorney general’s office, charged with investigating the old regime’s crimes—took over responsibility for the records to keep them from disappearing again. In its initial sweep, the Public Ministry estimated that the archive held 80 million documents, and workers immediately started going through them. Many got sick; the documents were impregnated with mold. Now workers wear masks.

Government officials found investigation records, license applications, officer commendations—and records of the movements of specific units during the civil war. Also, occasionally, they found evidence of murder. In 1979, Fernando Quevedo y Quevedo, a union leader at Coca-Cola, was shot to death. The archive held a hefty file on Quevedo y Quevedo: his movements, his politics. Finally, researchers found an internal report with just one line: “Quevedo y Quevedo killed by multiple bullet impacts.”

When the archive was discovered, Julio Solórzano had been working as a cultural affairs coordinator, touring the world with a Mexican dance troupe. That job had brought him into contact with Karen Engle at the University of Texas’ Rapoport Center for Human Rights. For two decades, UT had been involved in ongoing human rights efforts in Guatemala. Perhaps, Solórzano suggested, the center could coordinate with the archive.

“We thought it was important that the archive could always be accessible,” said Charles Hale, director of UT’s Teresa Lozano Long Department of Latin American Studies. “It needed to not be vulnerable to change or political whim in Guatemala, because conditions that made it possible for the archive to be open and stay open may not always be there.”

To protect the documents—and to make them accessible worldwide—UT helped the Guatemalans digitize them. On December 2, 2011, UT’s Benson Latin American Collection unveiled its new digital version of the 13 million archive documents catalogued so far. Since the site went live, it has received more than 105,000 page views, about 43 percent of which came from Guatemala.

According to UT archive researcher Kent Nowsworthy, the National Police Archive doesn’t usually yield anything as incriminating as the information in the Quevedo y Quevedo case. Most of the archive is administrative, and most of the evidence it reveals is on the order of placing particular police units at specific places at specific times. When researchers can combine such documents with other information—an eyewitness account of a kidnapping, for instance—the archive can be a powerful tool in tracking the disappeared.

This approach was used in the case of Edgar Fernando Garcia, a labor activist who disappeared in 1984. The prosecution found archive documents ordering the police Fourth Corps to cover a march where Fernando Garcia would be. They found documents commending two police officers, Hector Roderico Ramirez Rios and Abraham Lancerio Gomez, for an unnamed operation involving contact with two “subversives.”

“There’s no document that says, ‘Congratulations for killing this guy,’” Nowsworthy told me. “But working downward, the prosecution can say, we have documents pointing to the larger counter-insurgency campaign happening at the time, and that tie operations of the army with operations of the police. Then moving down, there are documents which specifically order the unit these guys belong to to cover this march. Other documents that explicitly label the march as a subversive activity. Then, finally, the commendation, which proves [the police officers] were there.”

In 2011, Ramirez Rios and Lancerio Gomez were found guilty of the forced disappearance of Fernando Garcia and sentenced to 40 years in prison.

Solórzano hopes the archive will help turn up internal documents about his mother. So far, he hasn’t found much, but he’s hopeful.

The archive has become a magnet for those in search of answers about what happened to their loved ones.

Sometimes the traces they look for are surprisingly faint. “I remember close to when we opened,” Brenner said, “a woman came to us looking for information about her daughter. The daughter was a violinist. She was studying to be in the national conservatory. One day she went out for her music lesson and never came back. Her mother went looking for her, but no one knew anything. No one could tell her anything.

“Finally she came to us. We went through the records. All we could find was a copy of the daughter’s application for an ID card. Just a form with her picture and fingerprints.

“I felt horrible. This woman came for answers, and I couldn’t give her any.

“But she wasn’t mad. She held the paper. She caressed it. She said, ‘Oh, niña, mi niña.’ Because at last, after everything, here was proof her daughter had existed. No matter what, here was something she could hold onto that proved her daughter was real.”

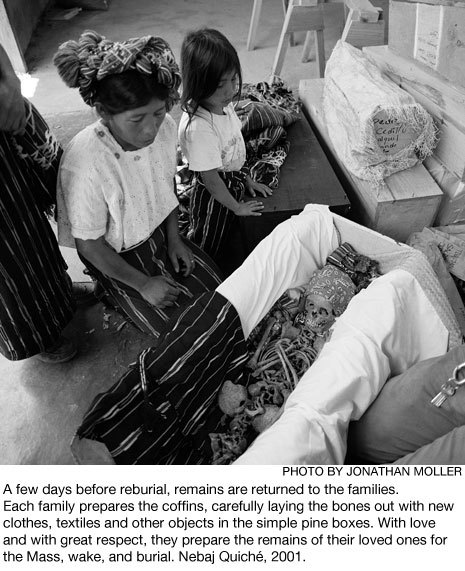

In a corner of La Verbena Cemetery, on the outskirts of Guatemala City, there is a rough excavation site ringed by cinder block walls and covered in prefab plastic roofing. At one side of the site is a long room filled with 11,000 black plastic trash bags. Each bag contains a body pulled from one of La Verbena’s four mass graves. If Alaide Foppa was anywhere, Solórzano had told me, she was likely here.

The site is run by the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation, or FAFG, the outfit primarily responsible for searching for the bodies of the disappeared. It has been the foundation’s job to dig up bodies, identify them and determine how they died. In the 17 years since its founding, it has become the biggest, best-equipped forensics outfit in Latin America. Its evidence has been used in many prosecutions.

The head anthropologist on site, Jorge Mario Barrios, walked me around.

“Most of these people aren’t desaparecidos (disappeared),” he said. “But a lot of them are. According to the other records, from places like the Police Archive, we think there are probably 300 here.”

During the period when Foppa disappeared, if you were abducted from Guatemala City, your body generally ended up in an unmarked grave at La Verbena, along with other unidentified bodies. If no one claimed the body, it would eventually be thrown into a mass grave. In 2008, FAFG investigators found four of these mass graves, each 80 feet deep.

We walked past a couple of forensics guys in face masks who were opening one of the trash bags, cleaning off one of the bodies. We came to a table where two anthropologists were putting a skeleton back together, piece by piece. Somewhere on site, a stereo was playing Nirvana.

“See here?” Barrios said. “The hips and skull?” He held up a piece of bone. “Totally shattered. Massive trauma. Probably a car accident. Died without ID and ended up here.”

“So not the police,” I said.

He sighed. “Probably not. But there are people they killed whose bones look like this. And there are ones like this”—he rummaged around a side table to pick up a skull with a bullet hole above the right eyebrow—“who might have been killed by gangs. But until we can identify all these people, we’ll never know.”

After skeletons are reassembled, anthropologists take DNA samples from the femurs to compare with that of the families of the disappeared. The foundation runs a national campaign, “Mi nombre no es XX,” or “My name isn’t XX,” asking anyone looking for relatives to donate DNA samples. (“XX” is how Guatemalan morticians record unidentified bodies, their version of “John Doe.”) The campaign has had partial success. Thousands of people—Julio Solórzano among them—have had their cheeks scraped for DNA. Many others are scared to come forward. During the war, showing too much interest in a desaparecido—even a family member—was a sure path to getting disappeared yourself.

That fear, Barrios said, is still alive, and it’s polluted Guatemalan society.

“People say Guatemala is a violent country,” he said. We were standing outside the camp, eyeing the two National Police guarding the place. He was smoking a cigarette. “They see that we’re second-highest in murders. They see robberies and attacks on buses. And we Guatemalans say, ‘Well, this is how it’s always been.’

“But that violence came from somewhere. Those bodies in the ground were put there by the authorities. The men who killed them are still free. They are still in power. I think much of the violence in our culture comes from that. Violence was done to the people, and the people responded with violence.”

“You think the connection is that strong?” I asked.

“Yes.” He thought a second. “During the early years of the human rights movement, when the military left death threats with human rights groups looking into the disappearances, they liked to say ‘Dejen que los muertos descansen en paz.’ [Let the dead rest in peace.] The government said, ‘We’ll kill these people, and you can’t do anything.’ And for a while they were right.”

He dropped his cigarette on the wet grass. “For a while.”

Progress toward justice in Guatemala has been slow; so slow that for a long time it seemed impossible that any of the perpetrators of the massacres or disappearances would ever stand trial. Guatemalan law allows third parties to prepare cases against criminals, and as soon as civil war ended, Guatemalan and international lawyers, prosecutors and human rights organizations started building cases against the generals—men like Efraín Rios Montt and his chief of armed forces, Hector Mario Lopez Fuentes.

For almost two decades, though, these cases were ignored. Until recently, only low-level perpetrators were tried. The men who pulled the triggers rather than the ones who gave the orders.

But in the last six months, several generals from the old days—Rios Montt, Lopez Fuentes and others—have been arrested and indicted for genocide. This is a groundbreaking development. The trials represent the first time in international history that a country has prosecuted genocide internally.

Solórzano thinks this will be hugely significant for Guatemala. But at the same time he acknowledges that the impact of the trials will largely be symbolic. The men who kidnapped his mother may never stand trial. Her body may never be found.

“The tragedy of the desaparecidos,” he said, “is that the crime never ends. Until they are found, you never get to know what happened. You never get to let go.”

Foppa’s story, so far, has no ending, just a question mark. Perhaps some finality may be found among the millions of pieces of paper in the Police Archive; perhaps there is no trace left at all.

There is a bitter irony to this. While in exile in Mexico, Foppa wrote a poem expressing the pain of being separated from her home country. “My life,” she wrote, “is an exile without return …

My life sailed

In a ship of nostalgia

I lived on the seashore

Looking towards the horizon:

I imagined one day setting sail

towards my unknown home

and the foreseen journey

left me in another port waiting for departure.

The dream of home led Foppa back, one last time, to Guatemala. At the poem’s conclusion, she asks, perhaps sardonically, what she fled. “There is no longer any promised land for my hopes,” she wrote,

There is only a land

full of withered desires

a secret, buried homeland

which from far away seems like

a lost paradise

Saul Elbein is an Austin-based freelance writer.