How Do We Fix Standardized Testing in Texas?

At UT last night, researchers, advocates and lawmakers shared some ideas.

Maybe you’ve heard. There’s a tremendous backlash spreading across Texas—and from here to the rest of the country—against the high-stakes testing regimen we rely on in the state’s accountability system.

More than 776 school boards, covering 85 percent of the students in the state, have passed resolutions calling for a more nuanced, less punitive approach to student and school assessment in the last few months. And that’s after the state began rolling out the new-and-improved testing system known as STAAR.

During its last session, the Texas Legislature faced an angry mob that railed, in vain, against a budget that cut billions from public education. A whole new mob, even more pissed-off than the last, is forming around the issue of over-testing, and could force lawmakers to make some testing and accountability reforms.

There are some serious differences of opinion, even among folks who agree the system needs to change. Last night on the University of Texas campus, five such leaders got together to share their ideas—a preview of the arguments we’re likely to see next legislative session. A few hundred teachers, activists, students and legislators turned up for the panel, which was hosted by the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs.

To begin, a pair of university researchers simply called for an end to the high-stakes system we have today, in which students’ test scores are used as the basis for judging schools and teachers. Angela Valenzuela, a UT professor of cultural studies in education, said it’s a battle she’s been fighting for more than a decade in Texas, because the pressure to test well—at the expense of a well-rounded education—falls disproportionately on Hispanic and black students.

Rice University’s Linda McNeil, a critical writer about standardized testing’s effects on schools, really brought the heat, calling out the “big money interests” profiting off the way we run our schools. With statistics she said came from a legislative staffer, she offered a chart that said Texas spent $39 million on testing in the 2000-2001 school year, but will spend $93 million on it this year. “Public tax dollars need to go with public education. You have a lot of people seeing education tax dollars as their opportunity to get rich,” she said.

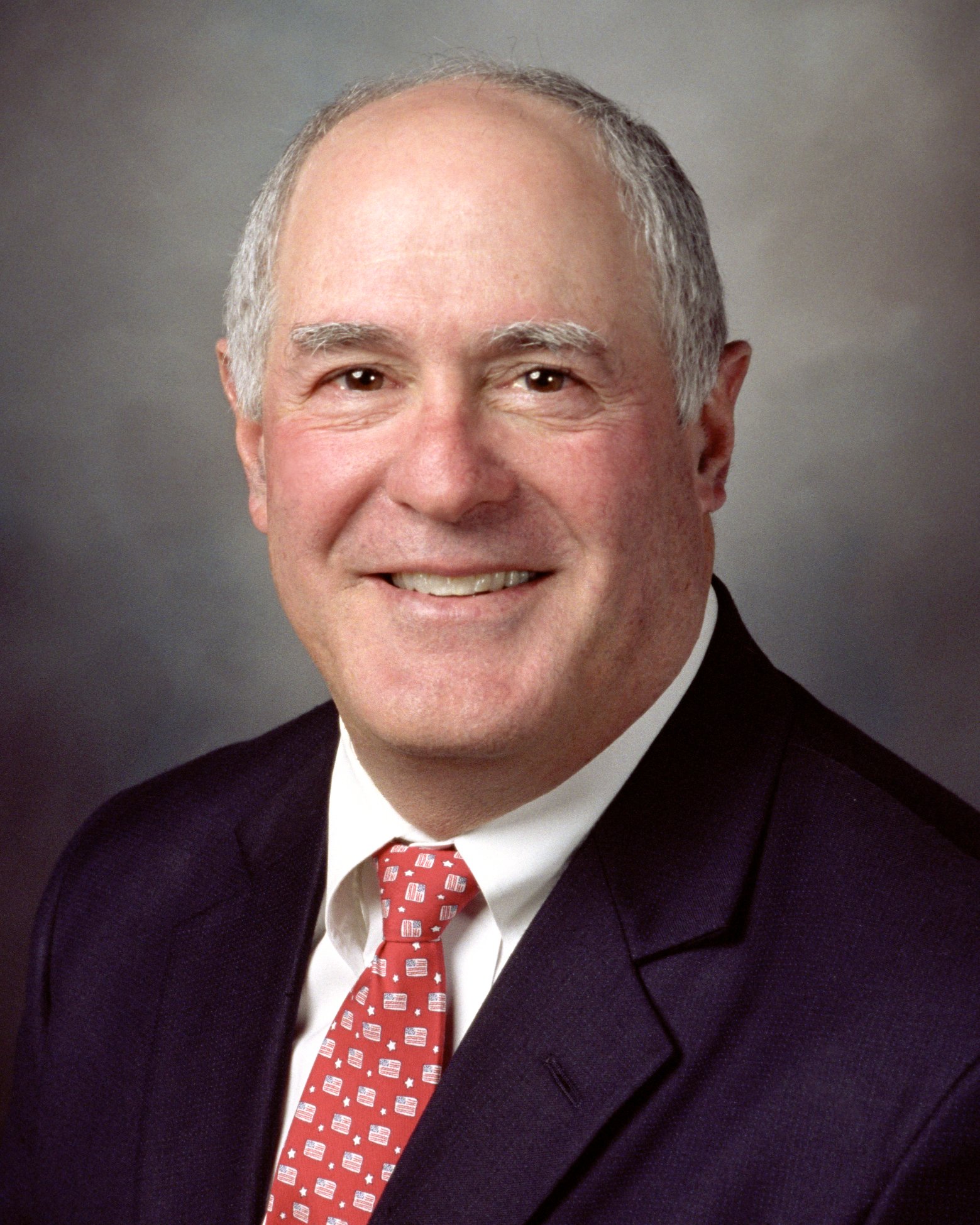

Texas Workforce Commissioner Tom Pauken has been an omnipresent advocate for career and technical training, which he says Texas has neglected in its zeal to boost college graduation rates. Monday night, Pauken called the current system a “trap” for kids whose ambitions don’t include college. “We’ve almost denigrated the value of working with one’s hands,” he said. Pauken warned of looming shortages in practical trades. “The average age of a master plumber,” he remarked, “is 56.”

David Anthony, from the education group Raise Your Hand Texas, said, like Pauken, that he’s supported bills to create “multiple pathways” to graduation in the past, and his group plans to do so again next January. “There is honor and quality of life in all work. Not just work that uses math and science,” Anthony said. “Texas is selling our students a dream that is not based in current reality.”

As evidence, Anthony quoted a pretty damning statistic from this first year of STAAR testing—that of the students who failed their STAAR tests last year and took remedial classes over the summer, just 20 percent passed their retakes. “You tell me which path those kids are on,” he said. “They’re already behind on their exams and they’ve only got 13 more to go.”

Todd Williams, education adviser to Dallas mayor Mike Rawlings and founder of a school reform group, Commit!, said he sees a particular problem in the way STAAR and TAKS scores are sliced to fit the needs of districts or the Texas Education Agency, and how hard it is to get meaningful test data. Parents might be heartened to hear their kid passed a state test, then be shocked to find out her “passing” score was under 50 percent. Of the 8,000 schools in Texas, he said, 93 percent of them were rated “acceptable” or higher by the state.

State Rep. Jimmie Don Aycock, a Killeen Republican who has a good shot at chairing the House Public Education Committee next session, struck a broad, conciliatory tone. He said he doesn’t think it makes sense to judge students, teachers and schools by a single test, but he asked for people to share specific ideas about, say, how to save money on testing. He said his mind was open, and that he’s focused on making positive change, with concrete ideas that can survive in the Capitol. Perhaps without meaning to bring down the party, Aycock underscored why the most likely outcome is no change at all, or very little.

“Simply saying ‘I don’t like what we’re doing’ doesn’t give us a bill,” he said.