Sins of Omission: One Little-Known Way Schools Can Cheat the System

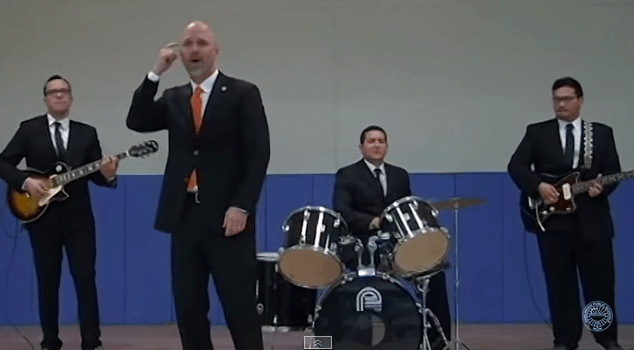

Above: El Paso's Bowie High School was Ground Zero in a cheating scandal that's shaken state regulators and schools across Texas.

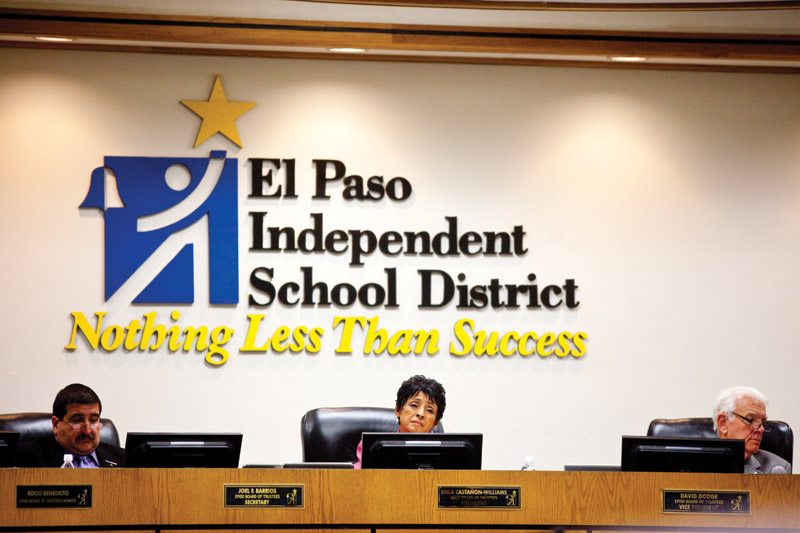

In the late 2000s, El Paso ISD’s schools were enjoying a miraculous turnaround under then-Superintendent Lorenzo Garcia. Schools that had struggled for years, and even faced the prospect of closure, were suddenly earning high ratings for their test scores and graduation rates. But Dan Wever, a retired former school board member with a habit of sifting through the district’s data for fun, sensed the numbers behind this miracle weren’t on the level.

For one thing, many of the schools’ 10th grade classes had become remarkably small compared to other grades (for high schools, federal ratings are based on their 10th grade scores). For another, some schools enjoying impressive turnarounds had begun a practice of exempting many students’ tests from counting toward the school average. All districts are allowed to exempt a few students’ tests for specific reasons. Back then, exemptions included recent immigrants with limited English, or special education students, and at EPISD’s Bowie High School, exemptions for special ed students jumped from seven to 31 from 2006-07 to 2007-08.

Wever’s source for all this was data from the Texas Education Agency’s website. He wrote to TEA about the spike in test exemptions, and says he never heard back. His concerns about the 10th grade enrollment, though, became the basis of two TEA “desk audits” from Austin—which cleared the district of wrongdoing—followed by a separate federal investigation. Which did not clear the district.

Lorenzo Garcia ended up in federal prison, top administrators left or were fired, and EPISD’s entire school board was replaced.

But Wever still wonders about those tests he suspects Bowie High swept under the rug.

“Everywhere else I’ve seen, the cheating is more mechanical—teachers changing the test scores. In Texas, we’re more sophisticated than that,” Wever says. “We’ve got people who really know how to cheat.”

There hasn’t yet been a reckoning of how those exemptions helped improve school ratings in El Paso, or if any other schools have been getting away with the same thing. It’s less obvious than other methods used in EPISD, but for a victimless little accounting trick, it’s an effective way to make your school look better to parents, neighbors, and the school boards that award your bonuses. All you lose is some small measure of the system’s integrity.

Here’s how it works.

Every year, Texas grades its schools based on students’ pass rate on the STAAR exams. Most people only ever hear that their neighborhood school is rated “exemplary” or “recognized” by the state. It’ll get even simpler next year when schools get A-F grades just like students. But those simple ratings are the outputs of an incredibly complex system that changes every year, spelled out in a monstrous TEA accountability manual few ever read.

One of those complexities is that schools can exempt some students from figuring into their overall pass rate. Inevitably, some kids are absent on test day, so they don’t count. Others transfer into a school mid-year. They get exempted too. Until recently, schools could claim exemptions for students in special education, or for recent immigrants with limited English.

Those last two exemptions are gone, now that the STAAR includes alternate versions for some students with special needs. But schools can still claim exemptions under a nebulous category called “other,” meant to cover any unpredictable test day interruptions—a poorly-timed fire drill, maybe, or a student throwing up on his test book.

That’s always been part of the system, and a few exemptions are totally normal. But when Wever checked the numbers beyond El Paso, he found some districts claiming exemptions far more freely than others. In some places, the exemptions vary wildly from one year to the next. Wever is particularly interested in districts where a school’s exemptions spiked the same year their state accountability rating went up.

“There’s nothing in here that’s gonna prove anything. It’s gonna give you indicators,” Wever says. “It’s like a treasure map.”

To pick one such example at random: Edinburg’s Anne Magee Elementary jumped two levels from “acceptable” to “exemplary” from 2006-07 to 2007-08. Over the same year, the percentage of its uncounted students rose from 4 to 15 percent, thanks largely to special ed exemptions, which jumped from five to 37. In 2007-08, South Dallas’ H.S. Thompson Learning Center earned an “exemplary” rating while leaving 30 percent of its students uncounted.

Under the new STAAR test, many districts still claim plenty of exemptions, either for “mobile” students who transferred in mid-year or for the catch-all “other” category. Some of the highest rates of exemptions appear in Killeen and San Antonio, where more military families probably moved in mid-year. Some charter schools also claim high exemption rates. At San Antonio Can High School, only 42 percent of students counted toward its passing grade in 2012-13. Washington Tyrannus School of the Arts—the largest school in the Shekinah Radiance Academy Chain the Observer has covered—exempted 42 percent of its students’ scores last year.

Wever says the key is that benchmark testing before the state tests can give schools an idea which students aren’t likely to pass the STAAR. By exempting a few of the right students, a school could boost its rating. Some districts even buy special software that advertises the ability to—in the words of one program, InovaPlus!—”Identify … who are the green/blue/gray students most likely to fail and who are the gray/yellow/red students most likely to convert.”

Schools are also graded on the passing rate for students of a particular race, students with special needs or who are still learning English. Some of those subgroups are so small, Wever notes, a district might boost its rating by keeping just a few tests out of the average.

“People don’t realize that it takes such low numbers to change these things,” Wever says. “If I were a principal and my job and my bonus depended on three kids not being tested, then they wouldn’t be counted. I think it drives people to do things that they wouldn’t normally do.”

Cheating scandals are almost as old as Texas’ test-based accountability system, which was one of the nation’s first. In some cases, like Garcia’s scheme in El Paso, the harm to students is clear: children are pushed out of school, told they can’t graduate or denied credit for tests they’ve rightfully passed. Other schemes, like the test exemptions, just add to the low-level hum of doubt about how much you should trust a school’s grade.

UT-Austin researcher Julian Vazquez Heilig has been studying this problem for years, and he says it’s the same problem behind scandals in Ysleta ISD and Houston a decade ago. “Schools identify the students that are problematic and can hurt their bottom line,” he says. “There’s all kinds of ways they do that.”

It’s simply baked into the system, he says. After every new fix, some other loophole appears. At the state level, TEA gets to decide what cutoff scores count for “passing” each test—to set the statewide pass rate. Districts have accounting tools like those exemptions for some students’ tests. You don’t even need a bunch of teachers doctoring the answer keys if you want to put your finger on the scales.

“What you see is the first-order cheating where it’s just egregious,” Heilig says, “but there’s all this second-order cheating where it’s less obvious.”

Even some of that obvious cheating has gone undetected, according to a damning state audit released this summer of TEA and its investigations clearing EPISD and Lorenzo Garcia. “The deficiencies in the Agency’s investigation of the systemic cheating that occurred in EPISD,” they wrote, “reflect the weaknesses in the Agency’s investigative processes for school accountability overall.” El Paso, in other words, is just the beginning.

The scandal has rippled across the state, sparking investigations of policies elsewhere that keep likely low-scorers—students from Mexico, often, with limited English—from counting toward the school’s average. Other El Paso-area districts, plus Uvalde ISD, McAllen ISD and Houston ISD have either been investigated by TEA or hired their own outside audits. Some state officials say the trouble surely runs deeper.

“I guarantee you that this is happening in every metropolitan area and in many other places,” state Rep. Naomi Gonzalez (D-El Paso) told the El Paso Times. “It just hasn’t been discovered yet.”

TEA does have a history of catching cheaters in the act. Even 15 years ago, a “truth squad” in the accreditation department investigated suspicious spikes in exempted tests, according to one former manager at the agency. When investigators caught Austin ISD gaming the system 14 years ago, this kind of cheating was still a novelty. Prosecutors back then said they had to make an example of AISD to prevent more cheating in the future.

As Lorenzo Garcia proved, there are still powerful incentives to cheat, and plenty of ways to do it. But since the Austin ISD scandal, TEA’s budget has been slashed repeatedly—less money for investigators’ salaries or travel to visit districts in person. Today, TEA staff has an automated system that looks for outliers in data they get from schools; a spike in exemptions can trigger a “desk audit” by the agency. But a public information request for any investigations into accountability fraud since 2009 returned only the few mentioned in the state audit, most part of the fallout from EPISD.

In response to that audit, Education Commissioner Michael Williams announced he’s creating an Office of Complaints, Investigations and School Accountability to ferret out rule-breakers among Texas’ more than 1,000 school districts.

State Sen. Jose Rodriguez (D-El Paso) says it’s clear TEA needs more money from the state if it’s going to be serious about catching cheaters. “There’s a need for the agency to be given the resources for the number of investigators they need, the money required to travel to the districts and do full-scale investigations,” he says. “The system needs a good review, and TEA, it seems to me … it just simply needs to do better.”

Last session he authored a handful of bills that toughened up TEA’s investigative powers. Now he hopes the Senate Education Committee will use the interim between legislative sessions to study what else TEA needs to do its job, and keep the accountability system honest. (Trustees at Canutillo ISD have gone even further, calling on El Paso-area lawmakers to seek an all-out restructuring of TEA.)

“As long as you have people that are willing to take a risk to circumvent the system,” Rodriguez says, “you’re going to continue to have these problems. And the people who will suffer are the kids.”