Inexplicable Deportation of Visually-Impaired Father Dashes His Hopes for Legal Status

Luis Antonio Perez-Morales almost certainly could have been among those whose lives were changed by the June 2012 immigration order that gave reprieve from deportation to people brought illegally to the United States as children. When Perez-Morales was 8 years old, his parents brought him from Mexico to Texas, and the state has been his home ever since.

“I remember me asking the Border Patrol why were they going to send me to Mexico if I didn’t even know that country,” Perez-Morales said. He hadn’t been back to Mexico in more than a decade. He grew up speaking English and going to school in Austin. In the evenings, he does housekeeping work in office buildings.

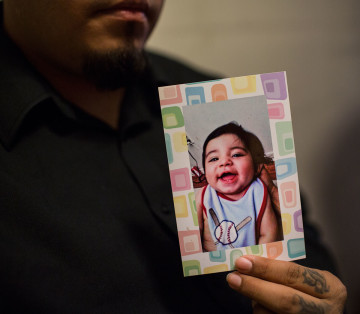

But in July 2013, he was deported to Mexico, leaving behind his two-year-old son Alexander, who is a U.S. citizen. Now, in a legal Catch 22, he’s no longer eligible for the status he probably could have gotten before he was deported.

“Luis’ case is a disaster,” said his Austin-based attorney, Jose “Chito” Vela. “It is one of the worst cases of Border Patrol abusing their authority that I have seen. Not in the personal abuse of him, but in the complete disregard for his rights that they showed, especially given that he had an obvious and serious disability.” Perez-Morales is blind in his left eye and has only partial vision in his right eye.

The Observer made repeated efforts to confirm the details of Perez-Morales case with both the Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). ICE spokeswoman Nina Pruneda, said “ICE doesn’t provide individual arrest record information” and referred the Observer to Border Patrol. In an email, a Border Patrol official said the agency “is not responsible for the detention or deportation of the aliens” and referred the Observer back to ICE.

Born in Guerrero, Mexico, Perez-Morales, 21, recalls when he was brought to the United States. “I got in the car, and we just drove off,” he said. “There was a lot of desert around.” His mother, Rosa Morales, said, “Just like everyone else, we were looking for a better opportunity for us, but mostly for him, because there’s a lot of discrimination against handicapped people [in Mexico].”

Since then, Perez-Morales’ family, including two younger siblings born in the United States, has lived in Austin. He said he didn’t even realize he was undocumented until he was in middle school. At Austin’s John H. Reagan High School, he struggled to keep up academically due to his vision problems. “It just got too hard for me,” Perez-Morales said. When he was a sophomore, he dropped out and instead enrolled in GED classes at Austin Community College.

It’s unclear why he was deported.

The night before, Luis and his friends had been driving around aimlessly, “just messing around, like kids do,” said Vela. Outside San Antonio, they were pulled over for speeding by a sheriff’s deputy, Perez-Morales said. His two friends handed over their Texas IDs, but when the officer asked to see Perez-Morales’ Social Security card, he didn’t have one to show.

“I thought of lying first, but then I was like, no, why should I lie?” Perez-Morales said.

Instead, he said, he handed over his matricula, an official ID issued by the Mexican government, and his Austin Community College ID. Within minutes, their car was surrounded by five Border Patrol SUVs. The agents then searched the car but found nothing, Perez-Morales said.

By then, it had been more than a year since the Obama administration announced its June 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Under the program, some undocumented immigrants brought here as children can receive a temporary reprieve from deportation. Later, the Obama administration fortified DACA by suggesting that Border Patrol agents should make those eligible a “low priority” for deportation.

Nonetheless, Perez-Morales was taken to a detention center after the car was searched, he said. He claims he was mislead into signing a voluntary deportation document that he couldn’t see well enough to read. He said he was told that he had to sign it before he could make a phone call.

Less than 24 hours after he and his friends were stopped, Perez-Morales was bused to Eagle Pass and dropped off at the international bridge, left to make his way into a country that was foreign to him.

“It’s the worst thing that can happen to a mother, when you know your son is being taken away,” Rosa Morales said. “And he can’t see. I was worried that someone would try to hurt him. He didn’t have enough money for the bus.”

For the next two weeks, he stayed with relatives before presenting himself to U.S. immigration authorities in Laredo, with Vela at his side. He was allowed to stay temporarily.

Perez-Morales had an appointment scheduled with Vela the week he was arrested to begin his DACA application. Had he applied before his deportation, he almost certainly would have gotten it. Approximately 83 percent of first-time applications for DACA were approved as of March 31, 2015.

Ilse Hernandez, a legal assistant at Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES), said that of the 465 DACA requests the group submitted in 2014, only one was denied.

Hernandez said that in her experience, intent to apply for DACA typically is all it takes to get out of detention. “Anyone who was DACA-eligible was pretty much safe if they said they would apply for DACA once they were released,” said Hernandez.

But Perez-Morales faces unusual hurdles in securing DACA.

Because of his deportation and two-week stay in Mexico, he no longer meets one of the DACA criteria — that candidates have never left the United States for “one or more absences that do not qualify as brief, casual and innocent.”

“[Border Patrol] ruined all of his opportunities to stay in the U.S. by removing him,” Vela said. “I think a reasonable person would look at the facts, and look at the situation, and think something weird happened here. Something unfair happened here.”

On Jan. 15, Perez-Morales’ DACA application was denied because of the deportation.

Perez-Morales and his attorney have since tried to extend his stay. They’ve applied for political asylum, humanitarian parole and cancellation of removal, all of which have been denied.

He has one last option. Perez-Morales and Vela plan to apply for what’s known as “deferred action” status, which could give Perez-Morales a year-long work permit, subject to renewal. If it doesn’t work, Perez-Morales could be deported as early as October.

“I just want to be here because of my son,” he said. “Not to cause trouble or anything. I just want to be with him, to watch him grow and everything.”