Editor’s Note: This cross-border investigation by La Verdad Juárez in collaboration with Lighthouse Reports and El Paso Matters, republished here by the Texas Observer, reveals new details of mass deaths at a detention center in Ciudad Juárez on March 27, 2023, when 40 migrants died after a fire was set in a locked cell—though the key and fire extinguishers were readily available. Leer en Español

Angry shouts came from inside the men’s detention cell at the Mexican National Migration Institute (INM) in Ciudad Juárez on the evening of March 27, 2023. A group of migrants inside the locked room argued with the center’s security guards and immigration officials over the lack of access to drinking water and food and their constant threats of deportation. Suddenly, the mood intensified, and the yelling turned into screams of fear and cries of distress.

The migrants pleaded for help to escape the room where the flames from sleeping mats formed a fire that quickly spread out of control.

Some of the migrant men who were at the center that day had been behind bars for weeks, and others entered only a few hours before the incident after being detained and transported to the immigration station during a field operation led by local Juárez authorities, INM agents, and the Mexican National Guard.

The migrants begged for the staff to unlock the door to the cell where dozens of men were trapped. Even as the fire spread rapidly, the personnel in charge of the well-being of these people did not take action to ensure their safety.

“We’re not going to open it [the door] for them. I told them already,” said an immigration agent as her colleagues looked for fire extinguishers and gathered the migrant women who were locked in another designated area of the building. The moment was captured on surveillance video with audio not previously published via a closed-circuit television camera from the INM station, providing clues to the events that unfolded that night.

The fire from the sleeping mats grew uncontrollably, and the toxic smoke filled the room, leaving 40 men dead from asphyxiation, another 27 with life-long injuries, and 15 female survivors with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), making this the incident in which most migrants have died under the custody of Mexican authorities.

Until now, injustice has impeded serious faults, abuses, and negligence from that night from coming to light. These actions contributed to the fatalities that occurred inside the overcrowded locked cell without fire extinguishers, ventilation, fire sprinklers, and working smoke detectors, a death trap for migrants from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Colombia, and Venezuela.

The deadly fire occurred at a time when the United States expanded its efforts to discourage migrants from arriving at its southern border under agreements with Mexican authorities. These laws led to massive concentrations of migrants to temporarily stay in border communities such as Juárez, a hotspot for thousands of deportees from the U.S. and migrants arriving from Central and South America in hopes of advancing north.

Almost a year after this tragedy, an investigation by La Verdad together with Lighthouse Reports and El Paso Matters reveals new details about the chain of events that unfolded that March night at the immigration detention facility located a few meters from the border with El Paso, Texas, where Mexican authorities held migrants who arrived in the city to cross into the U.S.

A reconstruction of the crucial minutes prior to and during the night of the fire was formed by analyzing various pieces of evidence, including the testimonies from eight survivors, interviews with emergency personnel who arrived at the scene, surveillance videos, an official investigation file, construction of a 3D model of the station, as well as the stories exposed during the criminal proceedings against 11 people, eight of whom are immigration officials.

The INM – a decentralized body of the Mexican Government– refused to answer questions regarding this incident that arose from this investigation and did not respond to interview requests sent in writing to the lawyers and family members of imprisoned individuals involved in the fire.

The first visible flames in the men’s cell at the Juárez migration detention center station are seen at 9:28 p.m. in a surveillance video from a closed-circuit television camera inside the public building.

Minutes prior, in a video without sound, the migrants are seen arguing with a security guard who is watching them sitting in front of the bars. The flames become visible, and immigration agents are seen walking outside of the men’s cell, approaching the cell bars, and exchanging words with the detained migrants at the moment.

A female security guard dressed in black approaches a female INM immigration agent standing in front of the locked cells and speaks to her. The guard leaves the area, and other employees follow her.

The immigration agent is presumably Gloria Liliana R.G. Her name and position coincide with the identity of the agent mentioned in the public hearings of the judicial process, where she has been present as a defendant.

The flames grow behind the vinyl-lined colorful foam sleeping mats placed against the bars by the migrants. Within seconds, the view of the inside of the men’s cell is entirely blocked by the smoke.

The security guard is later seen rushing through the migrant processing entry to the waiting room. “There is a mess!” she says in a surveillance video with audio.

Screams are heard, and people are seen running. In the background of the turmoil, a woman in a red jacket with two children is spotted in the waiting room. She is presumably Viangly Infante, wife of Eduardo, a 26-year-old survivor. Members of the Mexican National Guard also enter the station and head to the area of the fire.

“They already set fire,” the voice of a woman is heard, possibly belonging to immigration agent Gloria Liliana. She is then seen on the screen, walking by and holding a cell phone to her ear.

The commotion in that station’s area amplifies as security personnel and immigration officials come and go, looking for fire extinguishers.

“We need fire extinguishers, fire extinguishers,” a man wearing a black jacket, presumably Omar I. P. M., supervisor of the security guards on-site at the time, is heard saying.

“There aren’t any,” responds an immigration officer.

“Try using this one. Let’s see if it works, please…,” Gloria Liliana says.

The female immigration agent continues to hold the cell phone against her ear as she speaks and almost runs into the man in the black jacket. “All of this because they didn’t get water!,” she says.

“Yes, I talked to them since the morning,” the male INM official responds.

It’s 9:31 p.m., and the woman continues talking on the phone. “Hey, they are burning the station. I already told Daniel since they set many sleeping mats on fire. What can we do? There are no fire extinguishers. The smoke is in here already!” she says.

“We have to open the door,” a man’s voice is heard saying.

“No, we’re not going to (inaudible)… We’re not going to open it for them. I told them already.” A woman’s voice is heard without her being seen on the recording at that moment. She is presumably also Gloria Liliana, according to the surveillance video sequences.

Around her are employees of the security company CAMSA, contracted by the INM, two immigration officials, and a man not belonging to the migration institute who has not yet been officially identified. Sources recognized him as a processing agent or “coyote” who offers legal services to migrants.

Two minutes later, the sound of women coming out in a line is heard, followed by a verbal instruction, “Sit here, please.” A surveillance video of the exterior of the building later shows the women sitting on the front steps of the entrance.

The surveillance videos are evidence that the immigration officials and guards exited the area and left the male migrants trapped inside the detention cell. At no time do they try to open the cell’s door.

In an incident like this, a sound fire alarm should have been activated immediately, or 911 should have been dialed, and the building should have been immediately and completely evacuated, according to the Contingency Plan designed by the INM.

Minutes before the fire, in the middle of the commotion from the locked migrants, the agents celebrated Gloria Liliana, whose birthday was the next day, March 28.

One of her colleagues arrived at the beginning of the shift, at 8:00 p.m., with a cake and soft drinks and placed them in a room adjacent to their work area, next to the men’s cell. According to several INM sources and images of the videos reviewed for this investigation, the agents walked in and out of these areas.

Time rolled on, and the migrants screamed, ran, and asked to be released. After, they lit the mats on fire. Inside the locked cell, the flames grew, and everything filled with smoke, according to testimonies from interviewed survivors.

“I ran to a corner, jumped, and shouted, ‘Help! Open the door!’ And I didn’t see any immigration personnel even attempting to open them, leaving us locked in as if we were criminals.”

This is how Brian. F. Q from El Salvador remembers the scene. He is one of the interviewed survivors who asked to be identified by his first name and last name initials. He suffered injuries to a lung and kidneys and airway burns and was intubated for a month.

In a matter of minutes, the flames from the sleeping mats, presumably lit on fire by two migrants from Venezuela who are currently detained and under judicial process, generated a dense smoke that invaded the space.

Most migrants took refuge in the bathroom, seeking to protect themselves with water from running showers and even the toilet. The measure was insufficient to prevent them from inhaling toxic gases that were concentrated due to improper ventilation. The space was a dungeon, as there were no emergency exits.

“I couldn’t fully open the shower because I was so nervous. A number of people, about 50 people, entered that bathroom. I don’t know how many, but it was a huge number. Many, many, many people. We were breathing in front of each other, we screamed, and the smoke and fire were getting closer and closer,” said Stefan Arango in an interview Stefan Arango, another survivor who suffered a cardiorespiratory arrest and woke up inside a thermal bag outside the station after being left for dead.

Minutes before the fire broke, some of the detained men threatened the guards and agents with setting fire to the place to protest the conditions in which they were being held, according to several survivors interviewed for this investigation. They responded that they were late in doing so.

“I remember a migrant yelling if they [the guards] didn’t want them, if they weren’t going to let them out, they were going to start a fire. The immigration guard told them they should have done it long ago. That they had waited too long to do it,” said Brian F. Q.

The victims and INM sources consulted assure that the agents and guards at the scene addressed the migrants with insults and racist expressions, such as “Let them die!.” The interviewed individuals were not authorized to speak on the subject and requested not to be identified in this investigation.

“They were mostly insults. They asked what we were doing in this country and said no one loves us. They told us to get out of this country because we are not welcome here,” said Stefan.

The fire was started by the migrants as a means of protesting the conditions in which they were held, according to the Mexican Attorney General’s Office investigation cited in public judicial hearings of the case. The testimonies of two survivors reveal someone allowed at least one lighter to enter the men’s cell.

The victims agreed that both CAMSA guards and immigration officers administered physical inspections of the men before entering the cell.

The migrant men were locked up, although, in Mexico, undocumented migration is considered only an administrative offense, not a crime, as in the U.S.

The men’s cries for help faded with the flames and smoke inside the locked cell. The INM officially attributed the death of the migrants to the impact of the arson and to the loss of the keys that opened and locked the migrant’s cell.

Fifteen days after the tragedy, Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador declared that the person who had the keys to open the door of the cell where the fire occurred was not at the station that day, he stated during a national morning press conference on April 11, 2023.

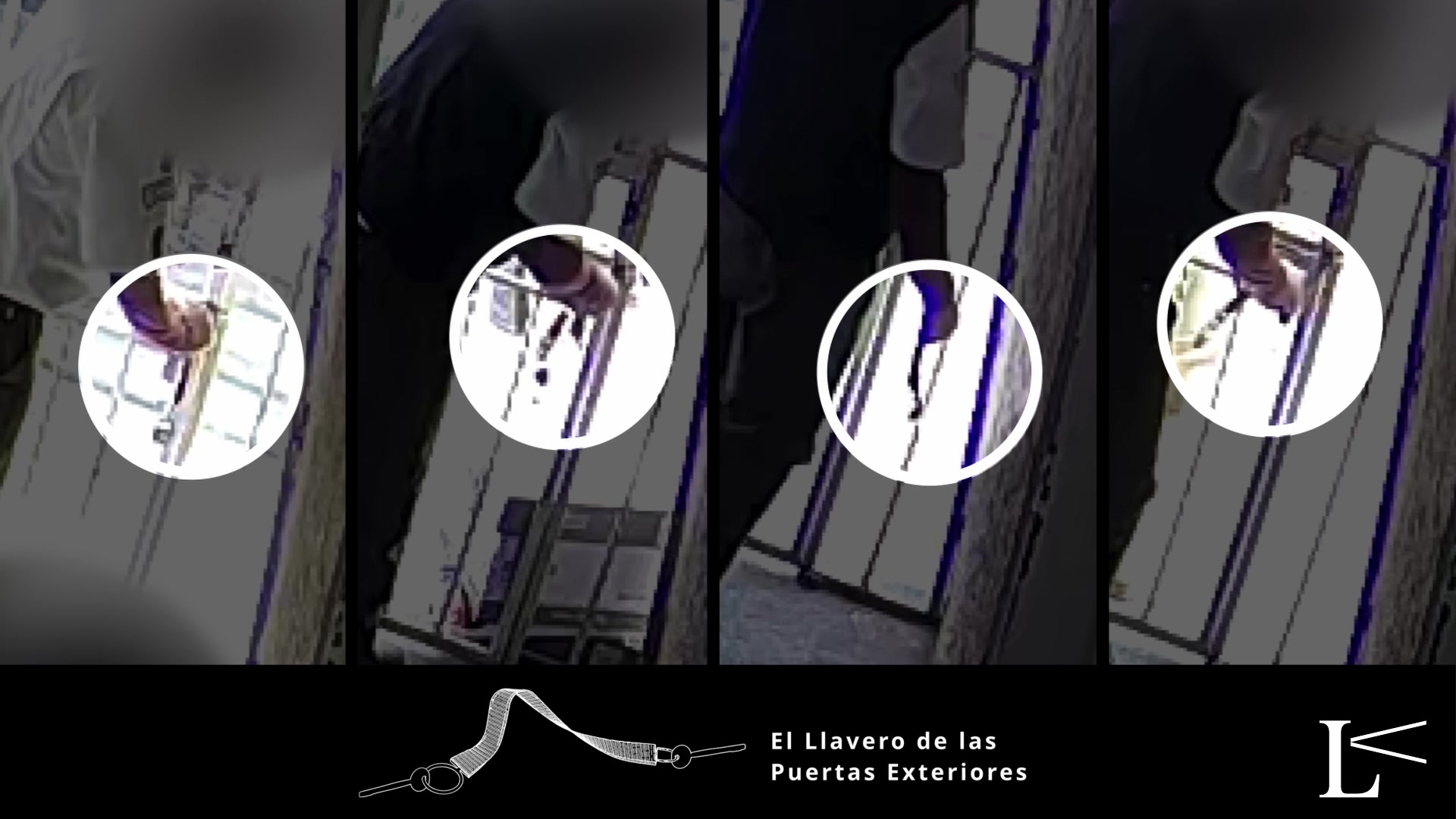

This journalistic investigation reveals that the cell’s keys were always inside the building. This conclusion comes from analyzing the images of 15 fixed security cameras that monitor the most critical areas of the building inside and outside the migrant center, day and night: the entrance, the administrative office, the guard area in front of the men’s cell, and the cell itself.

Although most of the images do not have audio, and the surveillance cameras inside the cell were destroyed by the detainees shortly before the fire, one of the videos with audio allowed us to hear an immigration agent say, “We’re not going to open it for them.”

The INM agents and the security guards are seen handling the keys throughout the day. According to the analyzed images, they open and close the main cell door and the side wooden and metal doors that lead to the building’s parking lot.

They enter and exit through the door to bring in migrants detained during an operation by authorities and to give entry access to staff members.

A few minutes before the fire, at 8:58 p.m., the security guard locks the wooden door that leads to the exterior of the building and immediately hands it over to the immigration agent in charge, who is in the administrative office. The key was last seen on the official’s desk in that office until the smoke blocked the cameras.

The key to the men’s cell main door is last seen just a minute before the fire breaks out when a security guard gives it to another colleague, and he places it in his pocket.

“They handled the door. They opened and closed it. I believe that immigration agents do use the keys to open and close doors,” said Stefan, who claims the men were kept locked up even when they were not deprived of their liberty and were not criminals.

The survivors wonder why the personnel did not attempt to open the door and left the men locked when they asked for help when the fire began.

“When it all started, I approached the door and said, ‘Help us, brothers, please. Don’t leave us here!’ And they told us, ‘Good luck, guy,’ and they left,” said Stefan in an interview, recalling his conversation with one of the security guards.

The security company’s supervisor assured the opposite in his testimony before the authorities. He said they did everything possible to save people’s lives and communicated this information to the head of the INM Representative Office in Chihuahua, Salvador G. G., after he questioned why the security guards did not break the lock. However, the surveillance images show they did not try to open the men’s cell.

The doors of the migrant detention area had to be padlocked to meet security protocol, according to Salvador G. G.’s statement. According to the investigation folder, the INM personnel in charge “must have or must know where the keys are located” during their shift.

That day, Rodolfo C. de la T. and Gloria Liliana R. G. were the agents responsible for the work shift., official documents show.

However, Rodolfo stated before the judge that that night, he left the immigration station at approximately 8:30 p.m. to transfer two minors from El Salvador to a shelter.

When the smoke engulfed the entire building, and the women and staff evacuated, a security guard retrieved the key to the door leading to the exterior of the building from a desk. As seen on the surveillance video, the key passed through several hands without anyone opening the cell.

The first firefighters arrived at the scene at 9:42 p.m., 14 minutes after the fire is visible in the images. It took them another 13 minutes to enter the cell as the building did not have ventilation, and the toxic smoke overflowed.

While figuring out how to enter the building, the firefighters came across another entrance to the cell through a double door; one wooden and the other metal.

Additionally, the men’s dormitory area had two metal doors; one welded and the other shut with a lock, according to a report on the activities carried out by the fire department.

“We access the property and begin searching because, due to the density of the smoke, there is no visibility. Even with the help of the lamp, the visibility distance is very short, so we crouch down and identify objects or whatever we find in our path. That is how we found a metal door,” said in a statement B.O., a firefighter cited at the hearing on April 17 in criminal case 235/2023.

One of the first firefighters to enter the room rescued the first body of one of the victims at 10:04 p.m. Then they took out other bodies and placed them on the parking lot ground.

Due to the density of the smoke and the heat accumulated in the men’s cell, the firefighters made a hole in a wall on the opposite side of the immigration station’s main door. While inside, they came across a padlocked metal door and broke the bolt.

After this maneuver, an immigration officer gave one of the firefighters a key.

“At that moment, while I was opening the padlock on the door, my colleague M.O. arrived and said that a guard had given them [the keys] to him. To which, by that time, we had already opened the gate by forcing the latch,” said firefighter R.D.F.H. in his testimony cited in a public hearing on April 17, 2023.

“Four of us entered doing search and rescue. We came across a door, but it was locked, and I exited to get a special tool to open locks. When I returned, a person wearing a white shirt and khaki pants, whose face or any particular details of the person I don’t recall, gave me some keys. I immediately returned to the scene, but my colleagues had already broken the lock,” said M.E.O.C., another firefighter. That information was cited in the same hearing.

Most of the victims were already settled on the asphalt of the INM parking lot when the rescuers arrived at the scene. There, they quickly evaluated the people who showed vital signs to transfer them to the hospitals.

Twenty-nine migrants were taken to different hospitals, and two of them died while receiving medical assistance. Another 38 were removed from the building without vital signs and placed in thermal bags in the parking lot.

“It was a shocking scene. Ultimately, there were many units there, many people working in the place, and above all, the most shocking thing you saw was when they took out one person after another person after another person. It seemed like a movie that would not end,” said Adrián Fernando Meléndez de la Torre, coordinator of the Mexican Red Cross of Ciudad Juárez’s Socorro area, in an interview.

Located a few yards from the U.S., the building that houses the INM immigration station facilities has operated in documented and reported hazardous conditions for 28 years.

Data from the Institute to the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) indicate that the provisional stay area “B” of the INM began operations in 1995 in the building next to the Reforma International Bridge, also known as Lerdo International Bridge.

Until 2019, the capacity for the center was 60 people, according to official data. However, by July 8, 2022, in a letter from the INM, the capacity reported was greater, of 80 men and 25 women, a total of 105 people. Yet, the total varies in another report, indicating a capacity of 110. This information contrasts even more with reality.

“The interviewed authority (from the INM) said it could accommodate 110 people, with 85 places for men and 25 for women. However, it could be seen that the station only had six bunk beds in the women’s dormitory, while in the men’s dormitory, they had to sleep on mats placed on the ground since they lacked bunk beds or a bed frame,” the CNDH documents.

After visiting the shelters and migratory stations in northern Mexico between January and February 2023, a report published in April of the same year says: “At the time of the visit, it was found that there were 17 women detained and that some of them had to share the same bed.”

According to research from the Diagnosis of the National Migration Institute, prepared by the Institute for Security and Democracy (Insyde) in 2013 and coordinated by Sonja Wolf, the station’s building is 1,405.31 square meters and is located on the same property as the federal subdelegation.

From then until 2023, as noted in the same report, the dormitories were prison-style cells in their structure and operating rules. They were locked with a key and built with bars, creating a threat to migrants.

“There was an emergency door on this side, but it was locked with a padlock. There was no way to open it. And if there were windows, they were too high,” said Brayan F.Q.

Another survivor, Brayan Orlando R.F. from Honduras, described the windows as 40-centimeter squares and were sealed, preventing ventilation.

These conditions turned the building into a death trap for the migrants who were detained on the night of March 27. Not only could they not escape, but they lacked ventilation when the sleeping mats were on fire.

At the time of the fire, five extinguishers were in the immigration building, but none of them were in the men’s cell. In addition, according to official documents, three of the fire extinguishers were not in the designated areas marked with signs obstructed by filing cabinets, files, and backpacks.

The extinguisher closest to where the fire started should have been about 10 meters away, in a hallway in an administrative area. However, only a hook and a fire extinguisher sign were found there.

About two minutes after the flames are visible in the video, an INM agent is seen looking for a fire extinguisher. The surveillance video shows that on his way through the institute’s administrative area, the agent passes by one device but does not seem to see it as he continues to walk.

Another fire extinguisher sign was in the offices in front of the men’s cell surveillance area, but no devices were there. One more sign with a device was located in an office near the women’s detention area, but it was presumably not used.

The agent walked 60 meters back and forth through the corridors to the registration module to bring a fire extinguisher, which took him 50 seconds.

After seeing the flames, “… I tried to open the wooden door (of the men’s cell that faces the outside). But I had no knowledge of how it opened or what locks it had. Unable to open the door, I went to look for fire extinguishers. Finding one in the Garita Reforma area, I removed the security seal and headed toward the area to extinguish the fire. Still, without success, since the extinguisher ran out,” the agent said before the Federal Public Ministry. His testimony was cited in the public hearings held on April 4 and 17, 2023, as part of criminal cases 216/2023 and 235/2023.

At 9:31 p.m., the same agent is seen walking toward the fire with an extinguisher in his hand; 41 seconds later, he stands in front of the area that was burning, in front of the bars where some of the migrants had placed mats to block visibility, and 20 seconds later he leaves that area with the fire extinguisher in his hand. He noted that he returned to the administrative area and put the fire extinguisher under a chair.

Survivors agree that there were no fire extinguishers in the men’s cell.

In the video captured by the cameras, it is observed that at 9:29 p.m., the officials and guards entered and observed the fire, and before two minutes had passed, they left the area. Only one immigration agent returned with a fire extinguisher, but this was insufficient.

“What I could see is that they were only there, if I remember correctly, for about 30 seconds or a minute, and I couldn’t see what they did to open the gate,” said Brayan Orlando R.F., a 27-year-old survivor.

He suffered burns to his airways and 20% of his body and was kept intubated in a hospital for two months. The incident left him with an injury to the brachial plexus – that is, to the network of nerves that goes from the shoulder to the extremity of the hand – which prevents the mobility of his right arm.

It is difficult to establish the trajectory and use of fire extinguishers in the area adjacent to where the fire occurred because the smoke obscured the cameras’ vision.

However, it was established there were five fire extinguishers in the INM building, and another four were brought there by Mexican National Guard agents stationed at the Reforma International Bridge, adjacent to the INM building, and by civilians, according to official documents.

An expert opinion on industrial safety, released in public judicial hearings, documents that there were four fire extinguishers in the immigration station. Three were blocked (two were in usable condition and another unusable,) and the fourth fire extinguisher showed signs of usage.

The quantity is different from the number of devices visible in the video analyzed for this investigation.

In his statement before the Public Ministry, released in a court hearing, Omar I. P. M., head of CAMSA’s security guards, said that when he noticed the fire, he ran to look for a fire extinguisher, but “he did not find one other than the one in the reception area.”

Although the men’s area did not have fire extinguishers, it did have a smoke detector. A total of seven devices of this type were installed throughout the Institute building, but on the night of the fire, they were all out of order. Six had no batteries, and the other was out of service for unknown reasons.

According to expert reports and documents obtained during this investigation, in the kitchen area of the INM, there was a smoke detector, but without the batteries.

Another smoke detector was in the men’s bathroom, and one more in the women’s bathroom, both without batteries. Another detector with a battery was found in a warehouse, but when tested, it did not work, although it did have batteries, the documents state.

In the “area of backpacks and belongings exclusively for minors,” in the administrative offices and a doctor’s office, were other smoke detectors, also without batteries.

On the day the tragedy occurred, survivors interviewed said everything went “as usual” that morning in the men’s dormitory, a place they describe as “a prison,” “lousy,” “dirty,” with bathrooms without privacy and very little water flow in the showers.

They said they felt “at peace,” although they had been thirsty since early during the day and had not been given water. They claim there were between 50 and 70 people in the cell, which doubled shortly after noon after a group of 50 or more men entered.

“Things started to get a little complicated because a certain group of South American migrants arrived, and the immigration officers and the guards who were there couldn’t control them. They made a mess and everything,” said Brayan F.Q.

One of the security guards declared to the authorities that the group of migrants came from an operation carried out by the INM itself. When they were brought to the station, their hands were tied with plastic zip-ties, which were removed upon entering the facilities.

The guard added that during the migrants’ entry, he realized that one of them had something in his hand and refused to show it. They struggled to take the item away and eventually pried a lighter from his hands. He reported this incident to the immigration shift manager and his supervisor.

That afternoon, there was not enough food, and the migrants were irritated. The survivors add that given the tension in the place, the Institute agents decided to quickly “dismiss” the disorderly group because they wanted to leave. About three or four hours later, they were taken away in trucks.

“We felt calm at that moment,” said Brayan F.Q. However, other survivors mentioned that in the afternoon, another group of migrants arrived, about a dozen men, mostly Venezuelans.

“From that moment, the hell which many of us experienced began. They arrived arguing with the immigration personnel and Mexican National Guard personnel because they were brought to the station,” said Brayan Orlando R.F.

The survivors said that the immigration personnel –without specifying whether they were agents or guards – far from calming them down and restoring order, provoked and insulted the migrants.

“He kind of incited them more to violence by asking them what are they doing in this country. ‘If you don’t like it, go back to your country. You don’t have to come here to fucking complain, is the word he used,’” said Brayan F.Q.

The situation became more intense, and he claims that one of the migrants shouted that if the staff did not want them there and were not going to release them, he would set the place on fire. “And the immigration guard comes by and tells them that they should have done it [start the fire] a long time ago and that it had taken a long time to do so,” he said.

It all happened in a matter of seconds, he said.

Almost a year has passed since the fire at the INM immigration facility, and the case has not gone to trial.

In addition, the Mexican Government has allowed the commissioner of the INM, Francisco Garduño Yáñez, to maintain his job as the highest-ranking position in the Institute even though he is linked to a process accused of his alleged responsibility in the series of omissions that caused the fire. He faces the judicial process while free and continues to lead the detention of migrants in Mexican territory.

The FGR accuses eight INM officials of the deaths of the migrants, including Garduño Yáñez, but only six face the process in prison. Three other people, two migrants from Venezuela and a private security guard, are also in jail for this tragedy.

Rear Admiral Salvador G.G, who was in charge of the Representative Office of the Institute in the state of Chihuahua, is in prison for the possible commission of the crimes of illicit exercise of public office, homicide, and injuries.

Daniel G.Y., the INM’s Northwest local representative (deputy director,) as well as the federal immigration agents Rodolfo C. de la T. and Gloria Liliana R. G., in charge of the station at the time of the fire, are in prison accused of homicide and injuries in the form of commission by omission. That is, for presumably not acting as guarantors or responsible for the safety of those in the immigration station on March 27 and for not helping the victims who were locked up.

Eduardo A.M., head of the Department of Material Resources and General Services, and Juan Carlos M.C., coordinator of the Beta Migrant Protection Group of the INM in Juárez, and who was allegedly part of the Internal Civil Protection Unit of the station, are imprisoned and accused of homicide, injuries and improper exercise of public service.

Another of the officials, Antonio Molina Díaz, also faced the legal process without being detained, and accused of improper exercise of public service. Still, he has allegedly been evaded since May 2023, when he was linked to the diversion of public resources from the Deconcentrated Administrative Body for Prevention and Readaptation Social, ordered by Genaro García Luna, former Secretary of Public Security during the six-year term of Felipe Calderón.

Security guard Alan Omar P.V. is accused of homicide and injuries in the modality of commission by omission.

Jeison D. C.R., one of the migrants accused of this tragedy, is linked to the judicial process for homicide and injuries in the commission of action because he was allegedly one of the two people who started the fire in the male detention area. The other migrant, Carlos Eduardo C.R., was accused of homicide, injuries and damages. Both are detained.

Until now, it is unclear why the men’s cell was not opened, who decided to leave the migrants trapped, and why the omissions and negligence that led to this deadly fire were tolerated.

“There is no justice… Justice here in this country is very… There is no justice, really. When it is about the State or institutions about the State, there is no justice.”

Said Brayan Orlando R.F., in an interview given in Juárez six months after the tragedy.

The 27-year-old man believes there are many things at stake in this case. Mainly people with power and a lot of money, which contrasts with the condition of the survivors and relatives of the victims who seek justice without financial resources or support.

Currently, Brayan is one of the 22 male survivors who entered the U.S. from Juárez on humanitarian parole last September. Seven female survivors who developed PTSD due to the incident they experienced at the INM station have also been granted humanitarian parole into the U.S.

Some of them crossed the border with their relatives, and although U.S. authorities released them on parole, they still face an immigration process that keeps them at risk of deportation to their countries.

“I would like justice, but I think it will be very difficult to achieve justice,” said Brayan Orlando R.F., who still faces an uncertain future in the U.S.

The fire inside the cell of foreign migrants on March 27, 2023, showed that the immigration stay in Juárez was operating under a series of irregularities and non-compliance with the protocols and provisions established in immigration law and those designed by the INM itself for emergency cases, including those caused by fire.

Several survivors of the tragedy reported seeing fire get started with the use of at least one lighter introduced into the cells. However, it is a banned object, as were smartphones that were used for live streaming the events in the cell that day.

“I saw that a young man, I don’t know his nationality, but I saw him enter [the room] with all his belongings. Most of us who were there did not know why he was able to enter with all of his belongings, with his phone, with his wallet,” said Brayan Orlando R.F.

The body search and registration of migrants before entering the cells correspond to federal immigration agents, in accordance with the Protocol for the Entry, Permanence, and Exit Process of Foreign Persons from Immigration Stations and Provisional Stays.

The survivors said the station allowed guards from the private security company CAMSA to conduct these inspections.

The Entry Process Protocol also indicates that the maximum time migrants can remain detained in the type B provisional stays, as the burned building was classified, should not exceed 48 hours.

During the tragedy, people were detained since February and March 24. Some of them are fatal victims, it was revealed by the judge at the public hearing on April 4, 2023, during the legal binding of three agents, a guard security, and one of the migrants accused of starting the fire.

In that same hearing, it was revealed the INM’s provision on the maximum time that migrants must remain in the stations is outdated since, due to legal reforms, it is currently 36 hours.

The officials and agents failed to comply with their obligations by not providing enough water or food. The Migration Law and the Regulations of the Migration Law say that, during their stay in the cells, migrants have the right to stay in a decent space, receive three meals a day, basic personal hygiene items, and medical care they may require.

At least six months before the deadly fire at the INM facilities, migrants who were in Juárez went from suffering from the erratic immigration policies of the governments of Mexico and the U.S. to living in a context of hostility and official persecution on this border.

Then, hundreds of migrants were stranded in this city, awaiting the resolution of their humanitarian asylum cases under the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) program, also known as Remain in Mexico, which forced them to wait in the country while their cases were resolved in U.S. immigration courts.

By September 2022, with the entry into force of the extension of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for migrants from Venezuela granted by the U.S. government, which protected them from deportations and allowed them to obtain work permits, a wave of People originally from this country came to this city to cross the border.

Thousands of Venezuelan migrants crossed the Rio Grande and surrendered to Border Patrol agents. This situation overwhelmed the U.S. authorities in carrying out their immigration process, so they were released from detention centers. They were left adrift in the streets of the city of El Paso, Texas.

Faced with the crisis unleashed by the inability to serve Venezuelan migrants, on October 12, in agreement with the government of Mexico, the U.S. launched a new immigration policy that consists of expelling Venezuelan migrants who illegally cross the border by land back to Mexico.

With this, under Title 42, the public health decree implemented at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic during the Donald Trump administration consists of immediately expelling migrants with the argument of stopping the spread of the virus. As a result, hundreds of migrants were returned to Mexico through this border.

Without money, food, and a place to spend the night due to the saturation of shelters in Juárez, migrants were left in limbo and forced to sleep on the streets during the cold fall weather.

Desperate, they began to wander along the banks of the Rio Grande, where they set up an improvised camp with the aim of keeping an eye on another change in immigration policies and, in the process, putting pressure on the U.S. authorities.

The camp grew to reach a thousand people or a little more, including entire families with children.

On October 31, a march by migrants seeking an opportunity from U.S. authorities to cross the border got out of control. It ended up being repressed by Border Patrol agents, who fired rubber projectiles and pepper spray.

Almost a month later, on November 27, authorities dismantled the Venezuelan camp set up next to the river with the support of riot police, leaving most of the migrants homeless because very few agreed to be transferred to shelters.

On December 8, the Government of the State of Chihuahua closed the passage to the caravan of migrants who arrived in the state from Central and South America by detaining them as they passed through the Municipality of Jiménez to prevent them from reaching Juárez and requesting their repatriation. However, a few days later, the municipal president opened the way for them and found trucks to help them reach their destination.

The people in the caravan sought to reach the border before the expiration of the deadline by which the U.S. would end Title 42, scheduled for December 21, when a stretch of the border of the Rio Grande dawned with troops and military vehicles of the Texas National Guard to close the passage to migrants.

At the beginning of 2023, on January 5, the U.S. government announced a new immigration policy in which it agreed with Mexico to return up to 30 thousand people per month of those who immigrate irregularly, in addition to extending permits for migrants from Venezuela with ties in the country. This program will be expanded to people from Cuba, Nicaragua, and Haiti.

These new actions kept the shelters for migrants in Juárez saturated, and hundreds of them remained on the streets as homeless. Hence, they began to ask for help, clean windows, and sell sweets in various parts of the city, mainly at crossroads and in the Center, to obtain food resources and rent spaces to spend the night.

The Municipal Government assured that due to this situation, they received citizen complaints, so they undertook police operations to discourage their stay in cruise ships and downtown areas, which detonated tension because migrants and activists accused the security forces not only of persecution but of stealing money, documents, phones, and belongings.

At the same time, the INM, with the support of the Mexican National Guard and Municipal Public Security, led immigration control operations on the banks of the river and raids on hotels to secure those who did not have valid permits for temporary stay in Mexico. to send them to cities in the center of the country.

Cornered and desperate, on March 12, hundreds of migrants demonstrated at the Paso del Norte international bridge to beg Joe Biden’s government to let them pass to the U.S. and to give them a prompt response to their asylum requests, which led to the closure of the crossing for almost seven hours.

This peaceful protest led to the tightening of measures against migrants to the point that the mayor of Juárez, Cruz Pérez Cuéllar, called on society not to give them money and warned that the “level of patience is running out.”

So it was. Actions against migrants intensified in the city with a joint operation led by municipal authorities, among which were elements of the Municipal Police, personnel from the Municipal Human Rights Directorate, and the System for the Comprehensive Development of the Family from the Municipality of Juárez (DIF), who accompanied the INM agents to arrest them and trick them into the provisional stay.

This was the case until Monday, March 27, when at least seven of the 50 migrants who were detained during the day in the operation were at the Institute station when the fire broke out, killing 40 of them.