El Paso ISD Begins Cleaning House After Cheating Scandal. But is it Enough?

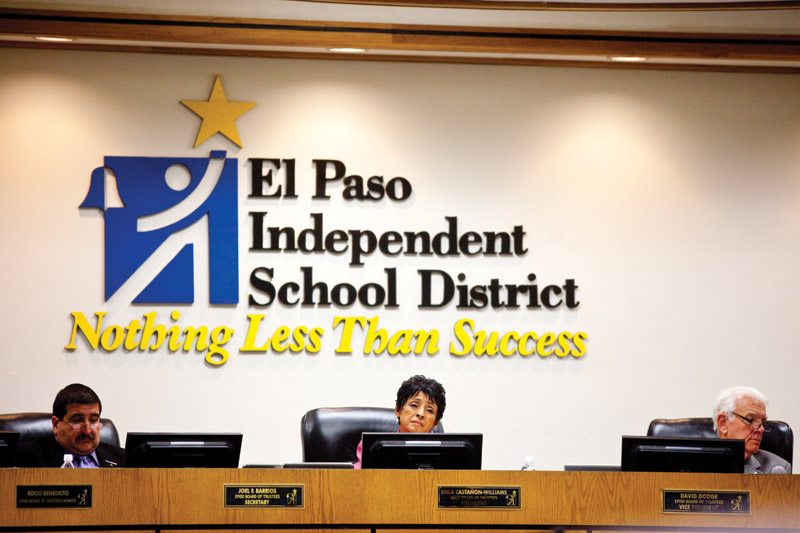

This time last month, I was finishing up a story for the magazine about the outrageous cheating scandal Lorenzo Garcia orchestrated in El Paso ISD. At the time, community members were irate because other than Garcia—who was superintendent during the years children were “disappeared” to boost the district’s test scores—no other EPISD officials had lost their jobs over the affair. The district leaders who talked about moving on from this sordid episode were, in some cases, the same ones who made it happen.

Less than a week after we put the story online, it looked like that was finally starting to change. Texas’ new Education Commissioner Michael Williams visited El Paso in October and told the district it had better start cleaning house, though he wouldn’t say how long he’d give them before levying more sanctions on the district, on top of its “probation” status with the Texas Education Agency.

On October 30, the El Paso Times reported the resignation of Jesus Chavez, former principal of Bowie High School, which became a model of the sneaky fixes Garcia espoused. Later that week Myrna Gamboa, the former director of the district’s Priority Schools Division (which included struggling schools like Bowie) bowed out rather than let the school board fire her.

Two assistant principals and a counselor at Bowie were also put on leave early this month. “It was either that or go in front of the school board and let them terminate me,” Johnnie Vega, one of the assistant principals, told the Times. “They want to look good for TEA so they’re not going to stop. Right now, it’s like a witch hunt.”

But if it is indeed a witch hunt, trustees are missing the biggest targets, says Steve Lane, a former high school principal under Garcia who retired in 2011 after refusing to take part in the scheme. “Instead of starting at the schools, they need to start at the top and work their way down,” he says. “The people they convinced to retire or kinda drove out of Bowie, those people are just pawns.”

One of those “pawns” was Kathy Ortega, the district’s former director of guidance services who retired in early this month. Many have blamed Ortega for not acting on a complaint from Bowie counselor Patricia Scott, who had questioned why school officials were erasing credits from her students’ transcripts.

Lane says Ortega is a great example of a mid-level player who was intimidated by Garcia and his top staff. After the TEA and the U.S. Department of Education had already cleared the district of wrongdoing, Lane believes if Ortega had passed Scott’s complaints to her superiors, she would only have brought critical attention to Scott. “Ortega, I guess could’ve tried to go to TEA or DOE again, but that lady was in a no-win situation. She was trying to protect Pat Scott. But nobody knows what to do, because who are you supposed to go to? Even though the evidence was overwhelming.”

If TEA’s threats don’t do the trick, there are two more pressure points that should worry those who enabled Garcia’s scheme. First is the ongoing FBI investigation that led to Garcia’s arrest—Garcia’s indictment included mention of “six unindicted co-conspirators” who still haven’t been named. Second is the state-mandated audit El Paso ISD had contracted out to the Austin firm Weaver and Tidwell (whose $580,000 bid was the only one EPISD received for the job).

There’s no telling how long the FBI investigation will last, but the district’s audit is expected to wrap up in February. Lane hopes one of them will finally force the district to go after the big fish nobody has the stomach to target so far.

“I wish they would, instead of going after the little people,” Lane says, “go after the corrupt people that caused all this.”