Are Texas Public Universities Just for Rich Kids?

As the Supreme Court weighs affirmative action, an Observer analysis finds few low-income students at major Texas universities.

Veronica Rivera isn’t like most University of Texas students. She’s from a small town in the Rio Grande Valley; she’s Hispanic; and she’s poor. On a crisp winter day, I talked to her as she was leaving the university’s financial aid office, housed behind a Windex-clean floor-to-ceiling glass wall on the third floor of the Student Services Building.

Most UT students—nearly half don’t file for federal financial aid—may never set foot in this office. But for students like Rivera, a sophomore majoring in communications, this place is central to their college experience. If they don’t get what they need here, they may not be able to continue attending UT.

Rivera grew up in San Benito, a city of about 24,000 residents, where she excelled in high school and graduated in the top 10 percent of her class, guaranteeing her automatic admission to UT.

Rivera’s mother lives on a $600 a month disability check. She can’t help Rivera with tuition, so Rivera has taken out between $2,000 and $4,000 in loans each semester. Rivera is also a recipient of the Gates Millennium scholarship, which covers expenses that her Texas Grant money and loans don’t. By the time she graduates, Rivera will owe between $16,000 and $32,000 in loans.

As a student coming from a very low-income family in an underrepresented part of the state, Rivera says that people at UT don’t always get where she’s coming from. Sometimes when she tries to tell them about her background, “they completely change the subject.” It makes them uncomfortable to hear about her family’s poverty.

A lot of Rivera’s friends are on financial aid and live on a tight budget. But, as she pointed out, “their families can still help them out…and I have friends who say, well, I have a three-bedroom house, my house is small, and I’m like, my house isn’t a house, it’s a shared home, and it’s one room.”

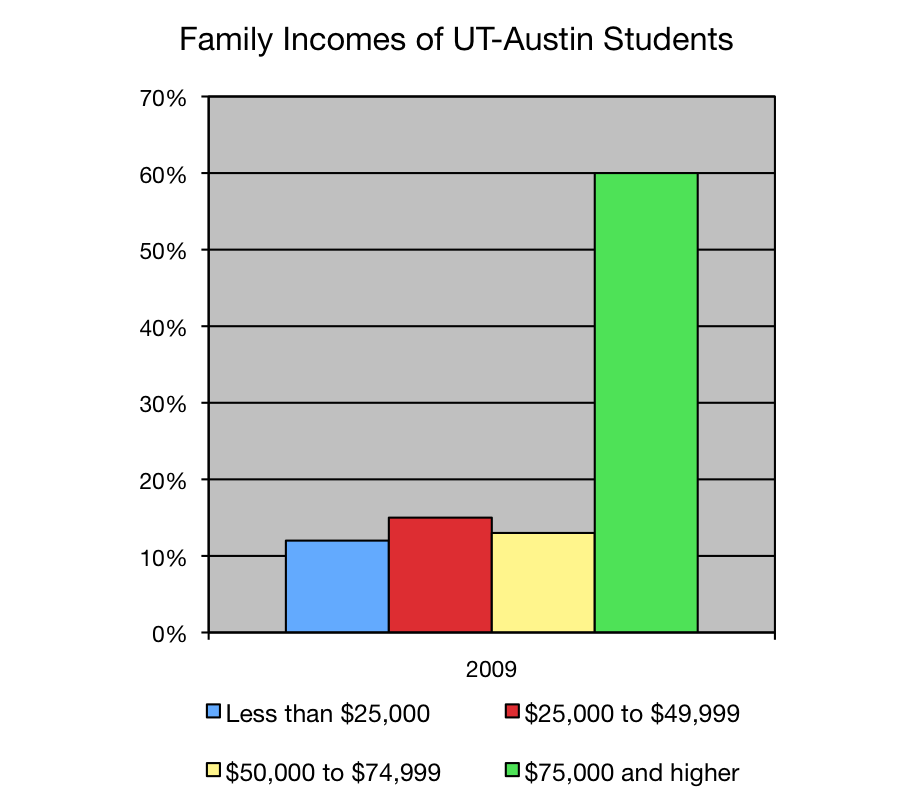

Rivera isn’t alone, but she’s in the minority at UT-Austin—and not just because she’s Hispanic. Though it’s seldom discussed, the number of poor and lower-middle-class students attending public four-year colleges in Texas is startlingly low, even as racial diversity has increased. At Texas’ top universities, like UT, the problem is even worse, yet it barely rates a mention among lawmakers or university officials.

That could change, depending on the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, which hinges on UT’s policy of considering race in its admissions process. The court heard arguments this week in the case, which began in 2008 when Abigail Fisher, a white woman, sued UT-Austin claiming that she was denied admission because of her race.

If the Supreme Court strikes down UT’s affirmative action program, the school could have even fewer Veronica Riveras. But the decision could also make class-based affirmative action more appealing.

Every year, UT releases piles of data on everything from the average SAT scores of incoming freshmen to the amount it spends on food service and swimming pools. But look for information on class diversity at UT—how rich or poor the student body is—and you won’t find much.

Through the Texas open records law, however, the Observer was able to obtain never-before released socioeconomic statistics for seven Texas colleges and universities. The numbers come from surveys conducted by UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute at hundreds of universities across the nation.

In addition to dozens of other questions, the survey asks incoming freshmen to report their family’s income.

The survey is voluntary and the universities don’t have to make the results public, although the Institute uses the aggregate data to track national trends. This data isn’t perfect because it’s self-reported by students when they’re at school (and possibly less likely to confirm family income with their parents). But it offers a rare glimpse at the considerable lack of socioeconomic diversity at UT-Austin and other public schools in Texas.

The numbers expose a higher education system that’s suffering from profound economic inequality. The more “elite” the university, the less representative it tends to be of the state’s economic diversity.

According to the survey results from 2009, a whopping 49 percent of UT-Austin students come from families making $100,000 or more a year, almost twice the median income for Texas families. By contrast, in the state of Texas just one-quarter of families make $100,000 or more. On the other end of the income scale, only 12 percent of UT students come from families making less than $25,000 a year. Among Texas families that number is almost 20 percent.

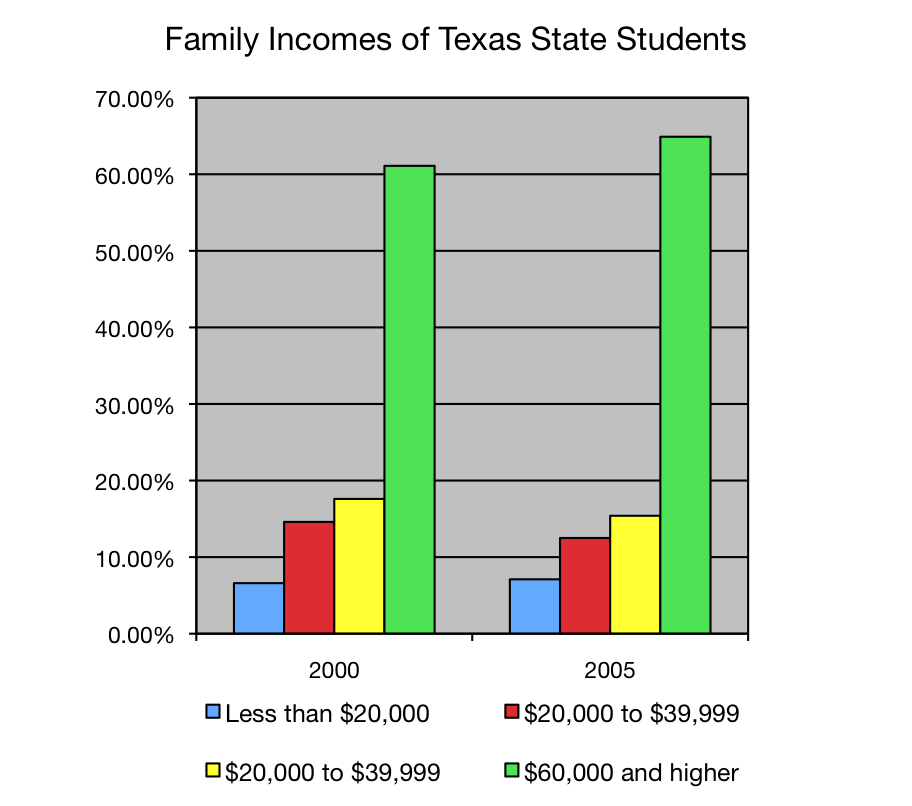

It’s a similar story at other Texas universities. At Texas State University in 2005, only about a quarter of freshmen came from families making the state median income or less. Up to 80 percent of the students at Texas State hail from families who report income above the typical Texas family.

Tarleton State University is a little more socioeconomically diverse than UT and Texas State, but still, only about one third of freshmen came from families making below the median income.

On the other hand, at Texas A&M-Kingsville, students were more representative of the school’s target population, which is largely low income and Hispanic: almost 60 percent came from families making below median income.

At UT-Austin, the CIRP survey data matches what two professors found in a comprehensive 2002 survey of 1,349 undergraduates from all programs and all four grade levels.

“As far as I know, this is one of the few studies of its kind in existence,” said Gerald Oettinger, an economics professor who co-authored the survey.

The professors found that the median family income of a UT student was $90,000: half were richer and half were poorer. The statewide median income at that time was $51,000. In other words, a UT family makes close to twice as much as a typical Texas family.

A few administrators expressed surprise at the paucity of low-income students at their schools. Betty Murray, director of the Tarleton State University Financial Aid Office, said “I wouldn’t have any idea—especially with the economy and everything—why it’s not more representative. …That kind of surprises me too.”

The scarcity of low income students in higher education should probably get attention in a state that claims to value equal opportunity and access to higher education. But it doesn’t. Schools don’t generally keep track of income information for all students and the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, which manages many aspects of higher education, doesn’t measure the family income of all Texas university students or try to address class as a potential barrier to higher education in our state.

“Closing the Gaps,” a program administered by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, is the state’s blueprint for addressing inequities in “student participation, student success, excellence and research,” in Texas higher education, according to the board’s website.

Texas colleges and universities have seen increasing racial diversity in the past 12 years since “Closing the Gaps” was instituted. Between 2000 and 2010, Hispanic enrollment in higher education increased by 88 percent and African American enrollment increased by 79 percent during that same period.

But Closing the Gaps doesn’t measure, much less address, the class inequities among Texas college students. When I asked why this was the case, Higher Education Commissioner Raymund Paredes pointed to former state demographer Steve Murdock.

“He was making speeches all around the state, saying that unless we significantly increase the participation of ethnic minorities in higher education in Texas, particularly Hispanics, that educational attainment and economic competitiveness of the state would diminish significantly,” Paredes explained. “Besides which, as I’m sure you know, there’s a very strong correlation between ethnicity and poverty.”

When I pressed him further, and asked whether he thought university admissions policies should give a leg up to low-income students as well as minority students, Paredes said that my questions showed “extraordinary naivete about opportunity in this country.”

He outlined the ways that poverty stacks the deck against children before they even get to elementary school. “Admitting students to universities doesn’t help if those students aren’t prepared,” he said. “I say over and over again, access without preparation is not opportunity.”

As for students who are prepared and have the potential to do well in college but can’t afford it, he said “there are 17 or 18 universities in Texas that if your family income is below $40,000 a year, you get your tuition fees paid for.”

He didn’t think any admissions advantage for low-income students was necessary, because getting a free ride to college was advantage enough.

But some research suggests that using race as a proxy to help low-income students ignores the barriers for poor kids.

A study by Anthony Carnevale and Jeff Strohl of Georgetown University published two years ago found that income and class obstacles are seven times as significant as racial obstacles in college admissions. This gap is caused by all the factors that often accompany poverty: a lack of educational opportunity, low income neighborhoods with few examples of academic success, under-educated parents, and a lack of expectation that children will go to college.

When I talked to former State Demographer Steve Murdock, at first he echoed Paredes. The socioeconomic “differences and disparities are so large” between minorities and Anglos in Texas that the best way to address class inequity is to admit more minority students, he said.

But Murdock didn’t stop there. He argued that Texas shouldn’t rely only on ethnic diversity to bring about socio-economic diversity in higher education. “I think we should look very carefully at their socioeconomic characteristics, and not just say, ‘Well, all Hispanics or all African Americans, etc. count the same, or need the same kinds of services,” Murdock said. Minorities from middle and upper middle class backgrounds don’t face the kind of obstacles that poor students of all ethnic backgrounds encounter, and college admissions should take that into account, he explained.

Some schools, like UT-El Paso, have done a very good job of admitting a student body that’s representative of the area it serves in terms of both race and income, Murdock pointed out. Yet most state colleges have student bodies that are significantly wealthier than people in the rest of the state. “Texas has made some progress, but boy, we’ve got a long way to go.”

Even students from middle class families making above median income struggle to pay for college.

At UT-Austin, living expenses and tuition push the school out of reach for many students. UT Financial Aid Director Tom Melecki said though there are dozens of aid and student loan options available, many students still can’t afford the school.

Melecki told the story of a promising admitted student whose parents made $40,000 a year in combined income—about $10,000 less than median state income. Even with grants, they would have to take out $10,000 per year in loans. The student didn’t end up enrolling at UT. Melecki said “this was a young man who was qualified to come to UT, and who we think could have really benefited in coming here, and that was very discouraging.”

It also doesn’t help that the 82nd Legislature cut almost $1 billion from higher education, shaving off 4.3 percent of its funding. That includes a cut of $10.4 million from the TEXAS Grant program, which serves low income Texas students attending college. Melecki explained that “with the reductions we’re seeing in federal and state grant and scholarship programs, it is becoming increasingly difficult for us to fund our neediest students who come from families where their incomes are below the state median.”

State Rep. Dan Branch (R-Dallas), chair of the House Higher Education Committee, touts community colleges as a solution to the cost problem of higher education. “The greatest financial aid program we have in the state of Texas by far is the low price point of our community college program,” he said. Rep. Branch praised a system that encourages low income students to attend two-year community college programs, then transfer to a four-year university.

Unfortunately, not many students end up making the transfer to a four-year college in Texas, or getting any degree at all. According to a Texas Tribune article from 2010, only 15 percent of full-time community college students get a four-year degree within six years.

State Sen. Zaffirini (D-Laredo), former chair of the Higher Education Committee, emphasized the importance of mentoring programs, work-study opportunities, and other services that make college affordable for low income college students. In particular Zaffirini praised the B Ontime Student Loan Program, which provides interest-free, forgivable loans to students who graduate on-time and with at least a 3.0 GPA.

Though B Ontime has been popular and successful, its funding was cut by a devastating 29 percent in the last legislative session.

So what can Texas do to include more low income students in higher education? UT Financial Aid Director Tom Melecki advocates for more campus work opportunities. Richard Kahlenberg of the Century Foundation and a few other higher education experts advocate for limiting merit-based aid, which favors middle and upper middle class students; providing more need-based aid; and giving an admissions advantage to students coming from low income families.

That last option may become increasingly appealing if the U.S. Supreme Court strikes down the last vestiges of race-based affirmative action in Fisher.

“Should the Supreme Court disavow” race-based affirmative action, wrote The New York Times correspondent Adam Liptak, “the student body at the University of Texas and many other public colleges and universities would almost instantly become whiter and more Asian, and less black and Hispanic.”

In such a scenario, an alternative would need to be found.

Some public opinion surveys have shown that Americans are more supportive of affirmative action based on class rather than on race. For example, a survey by the L.A. Times administered in early 2003 found that 60 percent of Americans said they supported economic based affirmative action, compared to almost 2-to-1 opposition to race based affirmative action.

“I think people have a common sense appreciation” for the fact that “today, the socioeconomic obstacles are far more important than the racial ones—so that’s why there’s a stronger support for the income based approach,” said the Century Foundation’s Richard Kahlenberg. Income or class-based affirmative action could therefore become the best option for including disadvantaged students in higher education.

The first step toward attaining economic equality in Texas higher education is acknowledging the need for more Veronica Riveras in higher education, and understanding the reasons why she’s in the minority.

Some of Rivera’s classmates started a group called Occupy UT Austin last Fall as part of the larger national Occupy movement. The group lists tuition increases and heavy loan burdens as the first two main points in its declaration posted online, and income inequality in higher education is among the group’s core issues. Occupy UT uses the university’s own motto to urge for reform:

“We say ‘what starts here changes the world,’ and now is the time to prove it.”

For Veronica Rivera, that idea goes beyond politics. When I asked her whether she ever considered leaving UT to go to school somewhere cheaper, less rigorous, and closer to home, Rivera said no. “It was my decision to come here and I’m going to stick with it.”

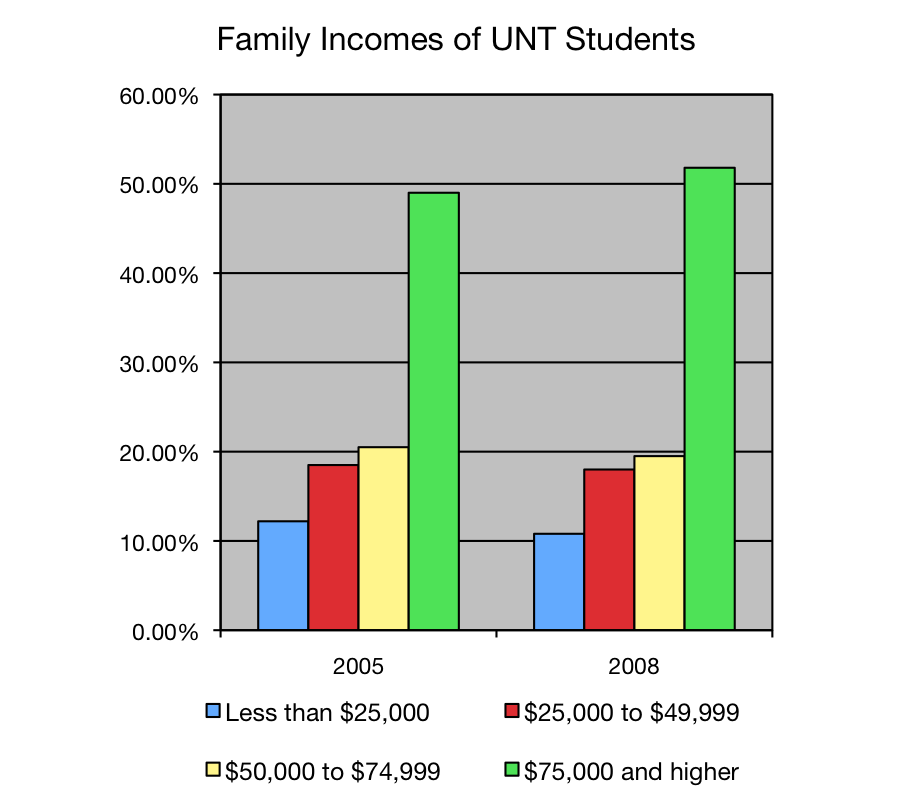

View samples of the CIRP survey data for Texas State University (2000 & 2005 ), The University of Texas at San Antonio (2001 & 2004) and The University of Texas at Austin (2009). This data includes far more than socio-economic information.