A Trial Reveals Depths of Drug-Related Corruption in Border County

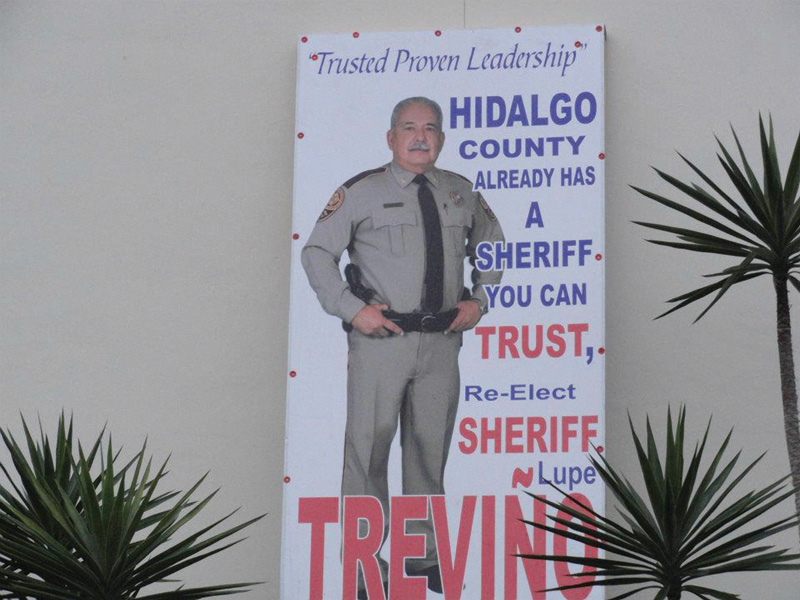

Hidalgo County Sheriff Guadalupe “Lupe” Treviño arrived at the federal courthouse in McAllen early Friday morning in a dark blue suit and red tie. He stood outside the courtroom with his hands in his pockets waiting for his name to be called by the judge.

Inside the courtroom, curious constituents, former employees, and numerous federal agents were waiting to see what the sheriff would do. For the previous three days former employees and convicted drug dealers had given damaging testimony about corruption inside the sheriff’s agency, about officers collecting campaign contributions from drug dealers and the sheriff’s direct knowledge of his son’s rogue drug task force.

“Will you plead the Fifth?” I asked him outside in the hallway.

“Why should I?” he said, indignant. “I’m not under investigation am I?”

The sheriff tried to act as though he had nothing to worry about. But the previous three days of testimony had made clear that he did have reason to worry.

It all started with Jorge Garza who would not go silently like the rest. Instead of taking a plea agreement and risking 10 years to life in prison, the former Hidalgo County deputy wanted his day in federal court.

Before the trial began it seemed that the scandal over the Panama Unit, a rogue drug task force run by the sheriff’s son Jonathan Treviño had already faded into a collective amnesia that sometimes overtakes the scandal beleaguered residents of the Rio Grande Valley.

When the federal indictments of the five deputies from the Hidalgo County sheriff’s office, and two cops from the Mission police department—the sheriff’s son and the son of the Hidalgo police chief—came down in December, the Panama Unit was front-page news. Residents questioned Sheriff Guadalupe “Lupe” Treviño’s involvement in the scandal. How could he not know that his own son, Jonathan, who lived with him, had been ripping off drug dealers for years?

Shortly after the Panama Unit bust, James Phil “JP” Flores who ran the sheriff’s crime stoppers program and 47-year old Jorge Garza, a warrants deputy were also indicted along with Aida Palacios, an investigator with the District Attorney’s office. According to federal indictments, the drug conspiracy centered on Fernando Guerra Sr. and his son Fernando Jr. — also indicted—who helped set up fake drug stings with the corrupt cops.

The Panama Unit, the Guerras and the other law enforcement agents indicted, preyed on drug dealers trying to move large loads of marijuana, cocaine and other drugs past the immigration checkpoint—75 miles north of McAllen—where the drugs could be sold in Austin and other cities for exorbitant profits. The corrupt cops ripped off the drugs and the Guerras sold the drugs locally at near wholesale prices, then they split the profits.

One by one over the past six months, the indicted members in the scheme plead guilty avoiding a trial. They are still awaiting sentencing. The 65-year old Sheriff Treviño, a powerful elected official and an adviser on border security to the Department of Homeland Security, had escaped the scandal.

But Jorge Garza, a former sheriff’s deputy, had different plans. His trial began a week ago in federal court in McAllen and will resume on Monday. The Panama Unit and police corruption in Hidalgo County is front-page news again. The trial testimony is being tweeted in real time on the front page of the McAllen Monitor’s site. The trial is providing a fascinating yet disturbing look at the enticing effect so much drug money can have on law enforcement and how it leads to police corruption.

In March, the Observer reported that former deputies alleged corruption, cronyism and campaign-finance fraud at the sheriff’s office. Treviño strongly denied the accusations. But multiple testimonies under oath over the past week have revealed damning evidence of campaign-finance fraud and corruption and of the sheriff’s direct knowledge of his son’s rogue drug task force, which terrorized Hidalgo County residents for years.

New Revelations

It’s difficult to pin down Edinburg attorney Lilly Ann Gutierrez’s strategy in defending Garza, whose name rarely comes up during the federal jury trial. Instead Garza sits at a table and stares into space or doodles on a note pad. When asked on Friday, Gutierrez, wearing purple-tinted glasses to match her purple sweater, only smiled and said she’d have more to say after the trial. In one week she had already subpoenaed former Panama Unit member Fabian Rodriguez, Commander Joe Padilla—Sheriff Treviño’s right hand man—as well as convicted drug dealers Fernando Sr. and his son, and James Phil “J.P.” Flores, former head of the sheriff’s crime stoppers program.

Their testimonies, especially Guerra Sr.’s testimony, brought new revelations of corruption involving cops from Pharr and Edinburg. The cops had assisted Aida Palacios, an investigator, in scaring off angry drug dealers who had lost loads to the Guerras. Guerra’s testimony also implicated Palacios’ former boss Charlie Vela and her aunt Mary Alice Palacios, a former Justice of the Peace. Vela was immediately summoned to the court to testify. Vela arrived and pleaded the Fifth Amendment on his attorney’s advice rather than incriminate himself. The district attorney fired Vela that same day.

“As a peace officer, I can’t have one of my investigators plead the Fifth Amendment in federal court without having it bring a dark cloud over the integrity of my department,” District Attorney Rene Guerra told the Monitor.

The Man with the Iron Fist

The week’s testimony often focused on Commander Joe Padilla, the sheriff’s right hand man. Guerra Sr. and his son as well as Fabian Rodriguez, a former member of the Panama Unit, testified under oath about kickbacks, campaign-finance fraud and corruption involving Padilla who has worked at the sheriff’s department for more than two decades.

It was Padilla who had tipped off the Guerras last year that they were the subjects of a federal investigation, according to Fabian Rodriguez a member of Padilla’s inner circle. “Guerra sent $1,000 to Padilla for the information,” he testified.

Both the older and younger Guerra also testified that they gave money to buy the sheriff a new fishing boat and frequently contributed to his re-election campaigns.

Garza’s attorney Lilly Ann Gutierrez sketched a picture of Padilla running the sheriff’s office with an iron fist and an insatiable desire for cash to get the sheriff re-elected. Padilla’s efforts pushed deputies to make corrupt alliances to secure more cash for campaign fundraisers. (In November, the sheriff won his third election with 80 percent of the vote.)

Rodriguez, the former Panama Unit officer, spoke about the fear Padilla instilled in deputies working under him. “Padilla has free rein and he puts the fear in people. I feared him even though I was part of his inner circle,” Rodriguez said. “I’m afraid as I’m testifying right now.”

Rodriguez said that Padilla would send deputies to shine his shoes, pick up his dry cleaning and pay his taxes while on county time. Padilla would also tell deputies to alter their time sheets to say they had worked overtime. Then they would use the comp time to work for the sheriff’s campaign. “Padilla wouldn’t put his name on it [the time sheet] because he didn’t want it coming back to him. He would tell someone else to do it,” Rodriguez testified.

There was an electric atmosphere in the courtroom when U.S. District Judge Randy Crane announced Thursday that Commander Joe Padilla had been summoned to testify. Padilla arrived in uniform straight from the office. Before Padilla was called to the witness stand, the judge said he had been informed that the commander was under investigation by the U.S. attorney’s office. “On the advice of my counsel, I plead the Fifth and will not answer further questions,” Padilla said.

Unlike District Attorney Rene Guerra, Sheriff Lupe Treviño did not fire Padilla for pleading the Fifth Amendment in federal court. Instead, according to the Monitor, “the sheriff was considering legal action against people making what he called slanderous statements about him regarding corruption in his department.”

The Panama Unit

On Friday morning, Rodriguez also testified at length about his role in the Panama Unit as well as the sheriff’s son, Jonathan’s role as leader of the rogue drug task force.

Rodriguez said he had worked in the crime stoppers office where he’d built a reputation for himself as a devoted campaign worker and someone willing to do whatever Commander Padilla wished him to do. “I would say my job was 50 percent police work and 50 percent campaign work,” he testified.

Rodriguez said he was drawn to the money and lifestyle that Jonathan Treviño and his friends in the Panama Unit enjoyed. “He always had a lot of money and he’d joke around and say, ‘I’ve got drug dealer friends.’”

In 2012, Rodriguez approached Sheriff Treviño and asked to be transferred to the Panama Unit. He became a member in October of that year. Rodriguez said that on paper Sgt. Roy Mendez was in charge of the unit, but in reality the sheriff called the shots and Jonathan ran the unit.

“So Sheriff Treviño was aware of what the Panama Unit was doing?” asked Garza’s defense attorney Lilly Ann Gutierrez.

“Correct,” Rodriguez said. ”The sheriff would be briefed on a daily basis.”

Rodriguez said the unit did both legitimate and illegitimate drug busts. Mostly, the unit stole only large amounts of drugs because it could quickly flip the shipments and make a profit, he said. “If we thought we could get away with it, we would do it.”

Jonathan Treviño would always take a bigger cut of the money than everyone else, Rodriguez said. “Only the people who worked the bust got the money. Jonathan would choose who came to the bust. And he would say how much money each person got.”

Eventually, Rodriguez said, he got “messed up in the lifestyle.” He found himself doing whatever it took to stay on good terms with Jonathan and his father, the sheriff. He wanted to keep his job and maintain his lifestyle. “If you crossed Jonathan, you weren’t going to be part of his group anymore. You were X’d out. He would tell his dad and he would make it happen. I went from one monster to the next—from Padilla to Jonathan, they were one in the same.”

Hidalgo County’s Top Cop

Early in the week, the trial had become a major topic of interest. But by late Thursday, it was the talk of the town when residents learned that Gutierrez had subpoenaed Sheriff Treviño to testify. What would the sheriff say to all of these allegations? Would he plead the Fifth like his top commander?

The sheriff strode into the courtroom to a hushed silence, all eyes on him. Judge Randy Crane advised him of his rights. “Have you discussed with a lawyer that you have rights against testifying if the testimony may incriminate you?” the judge asked.

“I’ve never talked to an attorney about this,” the sheriff said.

“The concern of the court is that you may be asked questions that may incriminate you… .”

“As an elected official, I believe the people of Hidalgo have a right to hear my testimony. I have nothing to hide unless the government says I’m the target of an investigation.”

“Your name has come up frequently. I don’t know if it makes you a target but you certainly might be one. But the court has no knowledge of it,” the judge said.

“I have nothing to hide. You can ask me questions.”

“There’s already been testimony of unlawful things such as the misuse of campaign funds… . I want you to know that before you testify,” the judge said once again.

Sheriff Treviño raised his right hand, swore an oath to tell the truth then took the witness stand.

Gutierrez asked a series of questions about his chain of command and about Padilla’s authoritarian style.

Treviño repeatedly rephrased her questions and often acted confused by her lines of questioning. “You confuse me easily,” he said at one point. “It’s impossible for any head of any law enforcement agency especially the size of ours to know what everyone is doing all the time.”

Treviño said he didn’t know anything about Padilla intimidating deputies into selling fundraising tickets, or forcing them to work for his campaign. “Padilla is not in charge of anything to do with my campaign,” he said. “Our fundraising is done by committees. … I am the campaign manager, but I don’t involve myself in fundraising. … I delegate fundraising to other people. My job is to go out in the community and shake hands, deliver my message to people.”

Treviño also said he had no idea that the Guerras were drug dealers and that with the exception of a $1,000 contribution from Guerra Sr.’s business Astro Trucking, which he had no knowledge of belonging to Guerra at the time, he had never received money from them for his campaigns or to buy a boat.

“So no one told you that the Guerras gave $10,000 to buy a boat for you?” Gutierrez asked.

“It’s absurd,” the sheriff responded. “It never occurred. I was not involved in it.”

“Commander Padilla asked JP Flores to get a donation because you wanted a new boat.” Gutierrez said.

“If anyone did that, they were using my name to solicit money and then keep it, “ the sheriff said.

He admitted to taking a pair of cowboy boots in 2004 as a gift from Julio Davila, a friend of the Guerras and also a convicted drug dealer. “No one ever told me that Davila was a drug dealer until all this came out,” the sheriff said.

The Next Chapter

The court recessed Friday afternoon. The sheriff left the courtroom muttering audibly, “Who’s the one on trial?” His testimony will resume early Monday morning.

Gutierrez, Garza’s attorney, has not even raised questions yet about the Panama Unit. As Gutierrez left the courtroom Friday, I asked her whether she had planned for the trial to mushroom into a larger examination of corruption in the county.

Gutierrez smiled. “I didn’t think it would get this big,” she said. “It’s certainly taken on an energy of its own.”