Where the Wild Things Are

The rubber Sasquatch head stared with glassy eyes from atop its pedestal. Beneath its gaze, Bigfoot Conference attendees milled about Tyler’s Caldwell Auditorium. Children peeked at the hairy visage from around parents’ legs. A pale man wearing black cowboy boots crossed his arms as a friend snapped a picture with his cell phone. Three teenage boys gave mocking thumbs-ups. Like the elusive or mythical creature that inspired it, the rubber Bigfoot was indifferent to the awe, curiosity and ridicule it provoked.

This was the vendor’s section of the ninth Texas Bigfoot Conference, held annually in the East Texas Piney Woods. Hosted by the nonprofit Texas Bigfoot Research Conservancy, the conference is dedicated to the large ape Gigantopethicus that purportedly crossed from Siberia to North America via the Beringia land bridge during the last Ice Age, 12,000 years ago. The ape’s descendants—usually described as bipedal, hairy and standing 7 to 9 feet tall—are most often sighted in rural forested areas receiving large amounts of rainfall, like the Pacific Northwest. Bigfoot also is said to roam the 65-million acre forestland along the Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas and Louisiana borders.

The conference aimed to separate fact from fiction. Mentions of the 1987 schlock film Harry and the Hendersons—in which John Lithgow takes a bumbling Bigfoot into his Seattle home—were met with tight grins by conservancy members. “A lot of us like to joke around, but we never play in the field,” said member Mike Street.

Stayton Bonner visits the Texas Bigfoot Convention in Tyler, Texas.

Attended by about 500, the conference mixed scientific presentations with folks hoping to make a buck off the creature’s legend. In the auditorium, American Museum of Natural History primate biologist Esteban Sarmiento lectured on great apes he’d studied in Africa, Sumatra and Borneo. National Book Award-winning naturalist-author Peter Matthiessen described a possible Yeti encounter in Tibet and said academia needs to keep a skeptical, but open, mind on undocumented species.

In the adjoining vendor area, a former standup comedian sold Sasquatch-themed hiking DVDs. Nearby, a Hollywood production designer hawked the Sasqwatch, a timepiece enclosed in a large, brown plastic foot.

“Everyone’s always real nice at the conferences,” Sasqwatch-creator Yolie Moreno said. “I’m just happy that Bob Gimlin is wearing one.”

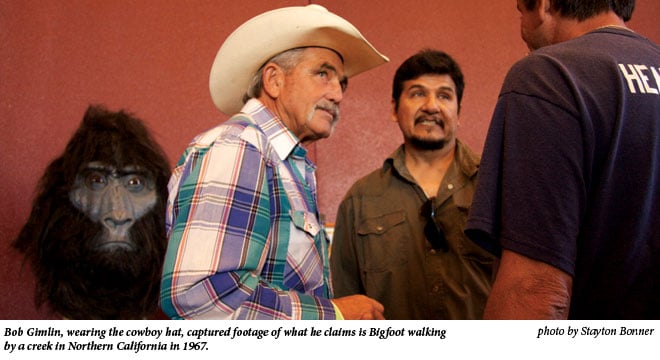

She nodded to a tan man with a white mustache, turquoise eyes and straw cowboy hat. He sipped from a McDonald’s coffee cup, talking with people. Along with Robert Patterson, Gimlin is famous for the only known filming of a Sasquatch. Shot on 16mm film in 1967, the footage shakily depicts a hairy creature walking upright like a man near a creek in Northern California. A regular feature on the History Channel’s Monster Quest, 78-year-old Gimlin is the Mick Jagger of Bigfoot conferences.

“I took so much ridicule over that for 40 years,” Gimlin said. “For a while I was really sorry that I’d ever been down there to see it. But since I’ve started meeting people at conferences like this one, I’ve enjoyed doing them.”

Another Bigfoot celebrity, Smokey Crabtree, scouted locations and starred as himself in the 1970s Bigfoot feature film The Legend of Boggy Creek, shot in Fouke, Arkansas. The movie’s YouTube trailer is replete with grainy Texarkana forestland footage and a Charlie’s Angels-style soundtrack. Crabtree self-published an account of the production, as well as the story of his real-life encounter with Bigfoot, Smokey and the Fouke Monster … A True Story.

“My son shot him three times with a shotgun,” Crabtree said, adjusting his cowboy hat and bolo. “It didn’t do him no harm at all, though. My son was 60 feet away and using squirrel shot.”

Crabtree pointed to a framed picture of a four-toed, 8-foot-long possible Bigfoot skeleton he discovered decomposing on a bed of Arkansas pine needles. “That’s not human,” he said.

He and his wife sold copies of his books and spoken-word CD, The Legend of Smokey Crabtree, next to a poster board covered with faded newspaper clippings. They depicted Crabtree’s other grapples with nature: a 200-pound alligator gar from the Red River in 1958, a 575-pound wild boar and a 37-pound bobcat trapped with grandson Skeeter.

“One of the biggest mistakes was making that movie,” he said. “I used to shoot ducks in my underwear from the back porch. When the movie caught on, 5 million people came beating down my door. I had to give my property away.”

A young hipster couple next to Crabtree promoted their Web site, BelieveItTour.com. Their logo—”As a child you believe. What happens then?”—depicted a cartoon Bigfoot attempting to hitch a ride alongside a white-sheet ghost and a green alien.

Conservancy members do not appreciate having Bigfoot ridiculed.

“There is a stigma attached to saying you’ve seen a Bigfoot or are interested in the subject,” said conservancy President Craig Woolheater. He squinted through rectangular glasses. “People will laugh at you. It’s lumped in with the paranormal—ghosts, witchcraft, UFOs, voodoo. That’s where the Bigfoot books are in the library.”

It takes a certain type of person to earnestly study a creature that’s largely been dismissed by the mainstream scientific community. And, judging by the conference, men seemed more likely than women to possess that perfect mix of curiosity, stuborness and a predilection for elusive hairy primates. “My sweet wife won’t ever come to these things,” said Gimlin, who had sighted the creature along rural back roads. A few spouses worked the ticket booth with the resigned tolerance that might be shown for nascar or wrestling.

I understood their feelings. My wife Catherine had agreed to accompany me to the conference. In an Austin boutique, she’d bought a T-shirt depicting a Bigfoot holding an American flag among pine trees. At the last moment, fearing conference attendees might take her shirt as mockery, she decided to wear her jacket and scarf as cover.

“You don’t seem like a believer,” one man told her. “Did somebody drag you here today?”

Like Dungeons and Dragons enthusiasts wary of a meathead jock, Bigfoot conference attendees and conservancy members sometimes hesitated to be interviewed. When I told them I was originally from Henderson, just down the road from Tyler, they became more at ease.

“Did you grow up hearing stories?” was a typical question.

I truthfully had to answer no. Most Bigfoot sightings occur around Texarkana and in the Big Thicket. Henderson falls between these two regions. I could think of only one person who, out of boredom, had spent nights searching for Sasquatch without ever discovering even a footprint.

Many conservancy members claim to have sighted the creature. Woolheater said he and his girlfriend saw Bigfoot walking beside a remote highway while driving from New Orleans to Dallas in 1994. Daryl Colyer sighted Bigfoot near the Trinity River in 2004, claiming the creature smelled “like a sweaty horse.” The conservancy maintains the creature has the population size of the jaguarundi (a medium-sized wild cat whose Texas population is estimated at less than 50) and the intelligence of an orangutan, and lives in the forest’s most remote sections.

“In my lifetime, I’d like to see credible evidence of this animal brought to light and public acceptance,” Woolheater said.

Representing a scientific organization that is largely shunned by academia, Colyer spoke indignantly about this treatment during his slideshow, “Bigfoot 101.” He mentioned University of Florida anthropologist David Daegling’s 2004 book, Bigfoot Exposed: An Anthropologist Examines America’s Enduring Legend. Fellow believers in the audience grumbled. Among other debunkings, the book states there is no scientific proof supporting the creature’s existence and that its recent resurgence is mostly because believers share stories over the Internet.

“My question to Daegling is, ‘Who’s been looking?’ ” Colyer told the crowd. “Do we have any teams out there right now heavily funded by a university? TBRC members do the best we can, but at the end of the day, we’ve got to go back home and put food on the table. We need funding. Money talks.”

Until a Bigfoot is killed or captured, believers hope for other evidence. Bill Dranginis sold his “EyeGotcha” surveillance video equipment at a vendor’s table. Cameras covered in metal grates could be fixed to trees. “Hair snares”—triangular-shaped metal tubes whose inner walls were lined with stiff steel brushes—could be baited and hung from branches to snag a section of Bigfoot hide for DNA study. During one presentation, conservancy wildlife biologist Alton Higgins said the group had spent over $50,000 for surveillance equipment in the Piney Woods. So far they had procured many images of black bears playing with hair snares.

“Do you think Bigfoot can smell the batteries in the camera?” a man asked Dranginis.

“That’s a good question,” he replied.

Believers blame the lack of evidence on the creature’s remote habitat, seemingly nocturnal nature, and the fact that most animals crawl into a crevasse or tucked-away spot to die. “We have 40 cameras out now,” Woolheater said, referring to a Texas-Oklahoma-Arkansas-Louisiana forestland roughly the size of Oregon. “Do the math. It’s very unlikely we’ll get a photo.”

As Dranginis explained the “Eyegotcha” method, American Museum of Natural History primate biologist Sarmiento began his afternoon presentation on the world’s great apes. With shoulder-length black hair, Sarmiento resembled Tarzan’s urban cousin. His slides, displaying many great-ape genitalia, resembled a college lecture. He said species were dying out as human populations encroached on their habitats. Neither negating nor confirming Bigfoot’s existence, Sarmiento said the Patterson-Gimlin footage was not of a great ape.

“The depicted creature’s large mammary glands are hairy, whereas those of humans or chimpanzees,” he said, clicking onto a new slide, “are clearly not.”

Squirming in their seats, a middle-aged couple glanced at each other over their young boy’s head.

Matthiessen, the keynote speaker, is a tall thin man with sunken eyes and gray hair. As late-afternoon attendees sat outside discussing college football or sightings, he leaned against a railing, scribbling on a legal pad. His 1978 National Book Award-winning travelogue, The Snow Leopard, recounts how Matthiessen saw what he believed to be a Yeti in the mountains of Tibet. He had been brought to the Texas Bigfoot Conference by his friend, John Mionczynski, a wildlife biologist who in 1972 encountered Bigfoot in the Big Horn Mountains, which stretch from Wyoming into Montana. Contemplating whether to write a book on the subject, Matthiessen paused to muse on Bigfoot and his worldwide brethren.

“People have a need for story and myth,” Matthiessen said, watching a crowd form around Gimlin. “Most scientists are very skeptical. And they should be. But they shouldn’t have a completely closed mind about it. Remember the coelacanth, a so-called fossil fish? It was believed to be 200,000 years extinct and then turned up 20 years ago off the Madagascar coast. I saw some myself in a tank while visiting the Comoros Islands. So, you know, stranger things have happened than Bigfoot.”

Matthiessen squinted into the humid afternoon sun. Two men with gelled hair, camouflage T-shirts, and fanny packs walked past.

“I’m all for mystery,” he said. “I think it’s going to be a very dull world when there’s no more mystery at all.”

Feeling trampled by Bigfoot, my wife decreed we put an end to the proceedings. After a stop at Starbucks, we sped away from Tyler. Office buildings and chain stores gave way to thick forest and red-dirt back roads. As Catherine unbuttoned her jacket, the T-shirt Bigfoot emerged from its hiding spot to stare at the quarter moon ascending the dashboard.

Stayton Bonner is a writer in Austin.