Hiking the Keystone XL Pipeline and Hoping for Dialogue

'Trespassing Across America' grapples with the damage inflicted on the planet by tar sands oil.

A version of this story ran in the July 2016 issue.

When Ken Ilgunas set off on foot to walk from Alberta, Canada, to Texas in 2012, opposition against the Keystone XL pipeline was at its height. A powerful grassroots coalition had coalesced around the pipeline, and protesters had successfully thrust the issue into the national spotlight. The movement, which began with rural Nebraskan ranchers and Native American groups, went on to galvanize hundreds of thousands of landowners and environmentalists throughout North America. The pipeline became a symbol for the climate movement, representing not just the immediate damage the pipeline would do to the environmentally sensitive lands it would traverse, but also the borderless devastation unfettered development of fossil fuels could wreak.

In his new book, Trespassing Across America: One Man’s Epic Never-Done-Before (And Sort of Illegal) Hike Across the Heartland, Ilgunas captures both the pipeline’s global significance and its local impact. He chronicles his 1,900-mile trek through bustling oil boomtowns and quiet prairie lands. Along the way, he’s chased by a herd of Black Angus cows, trespasses on ranchers’ private property, dodges mongrel dogs and has a run-in with a small-town Montana sheriff. The book is part adventure, part meditation on the state of the environment and American consumerism.

Trespassing Across America isn’t Ilgunas’ first attempt at an experiential travel memoir. In Walden on Wheels, a social commentary on the U.S. higher education system, Ilgunas chronicles a five-year period during which he works in a remote camp in Alaska, hitchhikes across the continent, enrolls in a graduate program at Duke University and lives in a van, all to pay off his student debt and avoid additional borrowing.

Trespassing Across America falls in the same genre — part memoir, part adventure — and the writing is both narrative and reflective. Ilgunas employs a kind of stream-of-consciousness style, which works well, given the inherent abstractions and wide-ranging implications of his subject. He uses his encounters with heartland residents and the media to contemplate human greed and largesse, as well as the damage that tar sands oil can inflict on the planet.

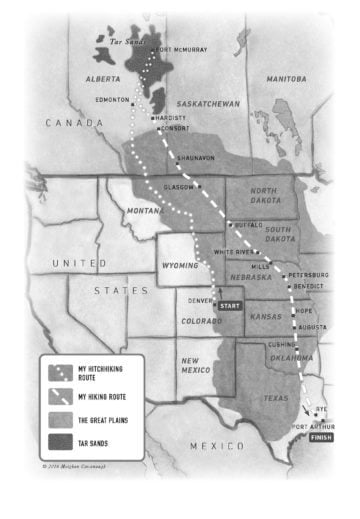

Ilgunas’ trek begins in Hardisty, Alberta, the heart of the tar sands industry, where he witnesses firsthand the curse of oil booms, and ends in Port Arthur. Along the way, he traverses Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma. He discovers that oil workers are paid handsomely, but many of the men, divorced from their families and living in trailers, turn to alcohol, drugs, gambling and prostitution. Ilgunas reflects on the impact of the tar sands industry on communities, questioning whether the pipeline will truly bring prosperity, as its supporters claimed.

In Whitmanesque fashion, Ilgunas waxes poetic on the beauty of the prairie as he walks through Montana, lamenting all the while the large-scale 17th century conversion to farmland and the accompanying destruction of ecological diversity. Further along on his hike, as Ilgunas hops over fences and crosses onto private ranches, ever fearful of gun-toting owners, he bemoans the United States’ hard-and-fast private property rules and compares them to European nations, where the countryside, irrespective of the owner, is open to the public for hiking and, in some cases, foraging. Americans’ narrow view of private property rights prevents the public from truly appreciating wilderness and nature, he argues.

At one point, Ilgunas reflects on a reporter’s question about the necessity of the Keystone XL pipeline, concluding that North Americans “have a funny understanding of the word ‘need.’” There is false need, he argues, which has resulted in North Americans using twice as much energy as Europeans. What we need is a “whole new relationship with the world,” he concludes.

Chased by cattle, fearful of armed and protective landowners, Ilgunas encounters more than his fair share of excitement on the five-month trek. But not only does he emerge unharmed, he’s met with hospitality and kindness along the way, even from people who find his brand of environmentalism anathema. Ilgunas is white, and one can’t help but wonder if a person of color would have received the same treatment if she or he had trespassed across America.

At the beginning of his trip, Ilgunas notes that he was going on a long walk for “the knowledge, the insight, the shock.” It was also an unprecedented trip that he believed would give him a deeper appreciation of the planet. But whether he truly gained a new understanding of the people who support the Keystone XL is unclear.

At several points, he meets and begins to confront the pipeline supporters — landowners benefiting from royalties, industry employees, political conservatives whose opposition to climate science is ideological. Sensing that they’re inflexible, he retreats in his conversations with them. He backs off from questioning their support for the industry that is the basis of their livelihoods and well-being of their families. He finds that oil and gas workers, in particular, are focused on the economics of now rather than the future of the planet.

Ilgunas’ failure to engage in honest dialogue about the pipeline is disappointing.

Perhaps Ilgunas is just being pragmatic, considering that he needs help, whether it be directions or a safe place to pitch his tent. Antagonizing people you need during an arduous trip isn’t smart. Even so, Ilgunas’ failure to engage in honest dialogue about the pipeline is disappointing.

It’s a problem Ilgunas seems to be aware of. In one of the last few chapters, he remarks that “not one person I encountered has said anything even halfway intelligent when denying global warming.”

As a result, the book fails to reach a satisfying conclusion. The enlightenment Ilgunas seeks about Keystone XL’s backers — why they support destruction of the planet — is elusive. Had he wrestled with that question more, the book would have taken on a deeper dimension.