Early one July morning in 2019, Bexar County sheriff’s deputies rolled down the quiet residential streets of Castle Hills with a pair of bombshell arrest warrants. The San Antonio-area bedroom community was in the throes of one of the biggest political scandals in its history. The deputies had warrants to arrest two of its major players.

Sylvia Gonzalez, a 72-year-old newcomer to Castle Hills’ city council, was at her eye doctor’s office when she received terrifying news. Her friend and fellow council member, 77-year-old Lesley Wenger, had already been rousted from her bed and carted off to jail. Now, deputies were looking for Gonzalez.

Gonzalez turned herself in at the county jail, and both women spent the day handcuffed, sitting on a cold metal bench. Their mugshots were splashed across local media. “Castle Hills councilwomen arrested in alleged plot to oust city manager,” reported one TV station.

Gonzalez says she ran for office that same year because city officials were neglecting Castle Hills’ infrastructure and alleges her arrest was part of a plot by rivals to punish her for speaking out. “I never dreamed this would happen to me,” she said in an interview.

The arrest warrants were sworn out by a prominent San Antonio personal injury attorney who volunteers as a part-time police officer for Castle Hills. The officer, who calls himself a special detective, alleged Wenger wanted to “get rid of City Manager Ryan Rapelye at all costs” and committed two felonies: fraudulent use of identifying information and tampering with or fabricating physical evidence. Gonzalez “wanted desperately to get [Rapelye] fired,” the warrant alleged, and had also committed the misdemeanor of tampering with a government record.

But Gonzalez and Wenger’s arrest warrants didn’t hold up under scrutiny. Within weeks, the Bexar County district attorney dismissed the charges.

In 2020, Gonzalez sued Castle Hills Mayor J.R. Treviño, former Police Chief John Siemens, and the volunteer special detective Alex Wright. A federal judge based in San Antonio initially rejected the city’s efforts to dismiss her case, after her lawyers presented evidence that the circumstances of her arrest were unusual and seemed to be retaliation for her actions as a council member. But, in 2022, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed that decision.

In its ruling, the appellate court adopted such a narrow definition of “retaliatory arrest”—a legal term referring to the disturbingly common practice of throwing critics in jail to punish them for speaking out—that Gonzalez’s attorneys say the decision makes it almost impossible to hold government officials accountable.

For their part, city officials are arguing that Gonzalez’s lawsuit should be dismissed because they’d simply done their jobs by reporting and investigating a crime. (Siemens didn’t respond to interview requests for this story; Treviño and Wright said they couldn’t comment about the pending litigation.)

Now, the U.S. Supreme Court is taking up this small-town dispute and wrestling with the issue of how someone like Gonzalez can prove they were unfairly singled out for retaliatory arrest.

“Arrests are going to become the weapon of choice for all city officials.”

Allegations that local officials abuse their power is a calling card of small-town Texas politics. In 2018, officials in the Hill Country town of Ingram fined a local business owner after he asked for records under the Texas Public Information Act—in retaliation for the request, his attorney later alleged in court. In 2021, a judge found that the Austin suburb of Bee Cave had illegally removed a council member who’d criticized city policies. Under the Fifth Circuit’s ruling, it would be easier for all of them to sue than it would be for Gonzalez, though she suffered the trauma and humiliation of a highly publicized arrest. That’s why, her attorneys say, the decision incentivizes vindictive public officials to use police against their opponents.

The Fifth Circuit too narrowly applied an earlier Supreme Court decision, according to Gonzalez’s lawyers. At the very least, they’re asking the high court to let them present statistical evidence that they say shows she was singled out for arrest in violation of her free speech rights.

But they also argue that the appellate judges misused a rule meant to protect police officers from being sued over split-second decisions and not meant to shield city officials who spent weeks obtaining a warrant to arrest a rival. If the Fifth Circuit’s interpretation is allowed to stand, “Arrests are going to become the weapon of choice for all city officials,” Anya Bidwell, one of Gonzalez’s lawyers, told the Texas Observer. “We just can’t have a system that treats arrests more leniently than other ways of punishing your critics.”

Castle Hills, population 4,000, is one of those former suburbs that long ago was enveloped by San Antonio, which has a population of nearly 1.5 million. But the 2.5-square-mile enclave maintains its own elected officials, city manager, and police force. Current and former residents say Castle Hills is susceptible to petty infighting between small-time politicians who’ve built their own fiefdoms.

Gonzalez moved here in 2001, drawn by good schools and proximity to her parents. She’d grown up in the region; her father was San Antonio’s first Hispanic assistant police chief.

In a recent interview, Gonzalez told the Observer she ran for office because she was frustrated with Rapelye, the city manager. Castle Hills is small enough that residents expect the city manager to personally return their phone calls. Gonzalez said Rapelye never responded to her and that she heard similar complaints on the campaign trail. “If you were connected with the city, you got things done,” she said. “But if you weren’t, you could wait and wait and wait.” In 2019, Gonzalez narrowly unseated an incumbent council member.

Today, Gonzalez characterizes herself as having taken on an entrenched political clique that protected the city manager. It’s difficult to imagine so much drama in Castle Hills, where the city council oversees an annual budget of $7.5 million, about 0.2 percent of San Antonio’s. Some council members work at prominent institutions in the country’s seventh-largest city, but such big-city perspectives don’t seem to temper how seriously locals take their politics.

Other city officials and their allies also saw the situation as high-stakes. In court, Gonzalez and Wenger’s critics alleged that the two women “conspired” to remove Rapelye and reinstall a former city manager. Police alleged that Wenger planned to “give the job to her very good friend.”

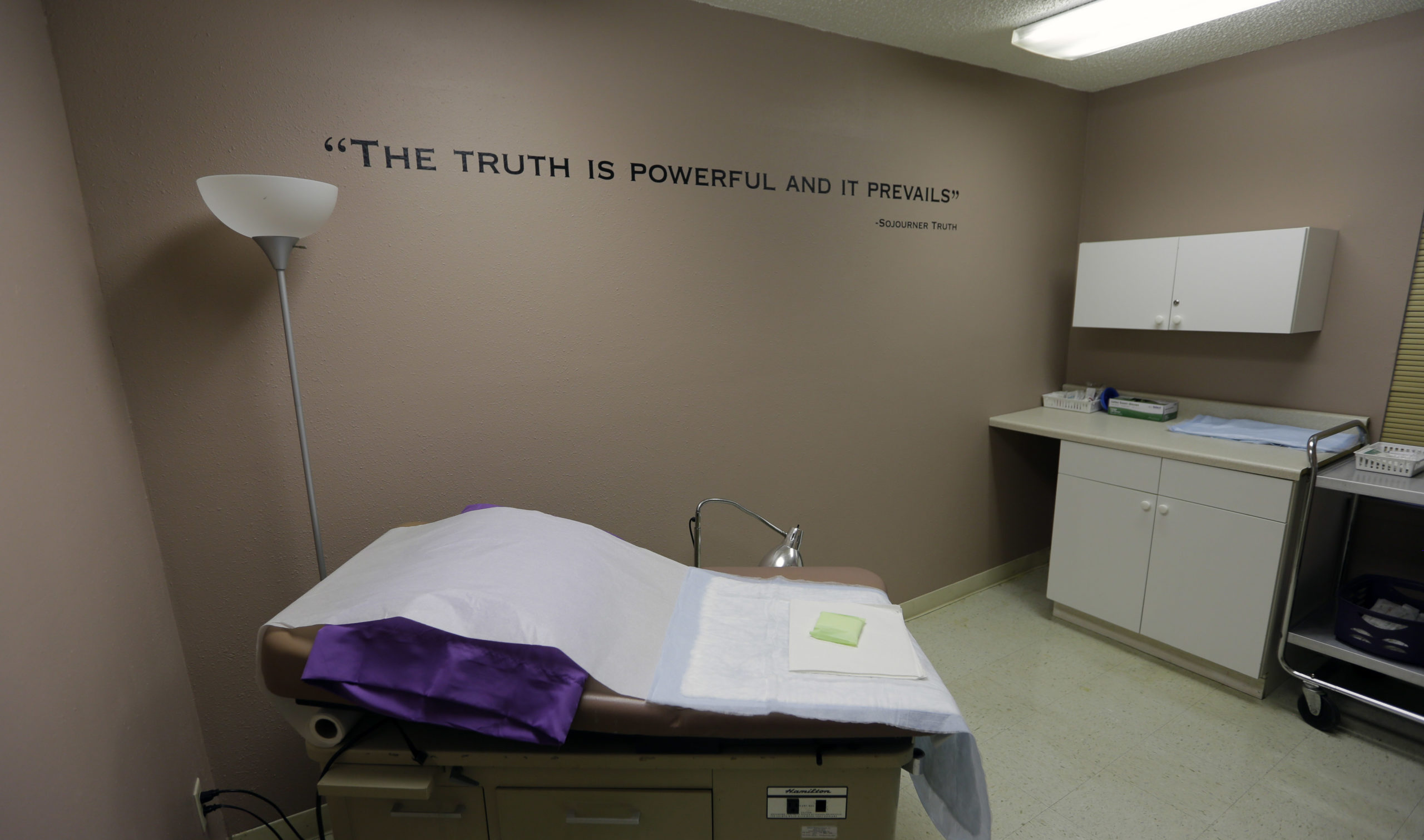

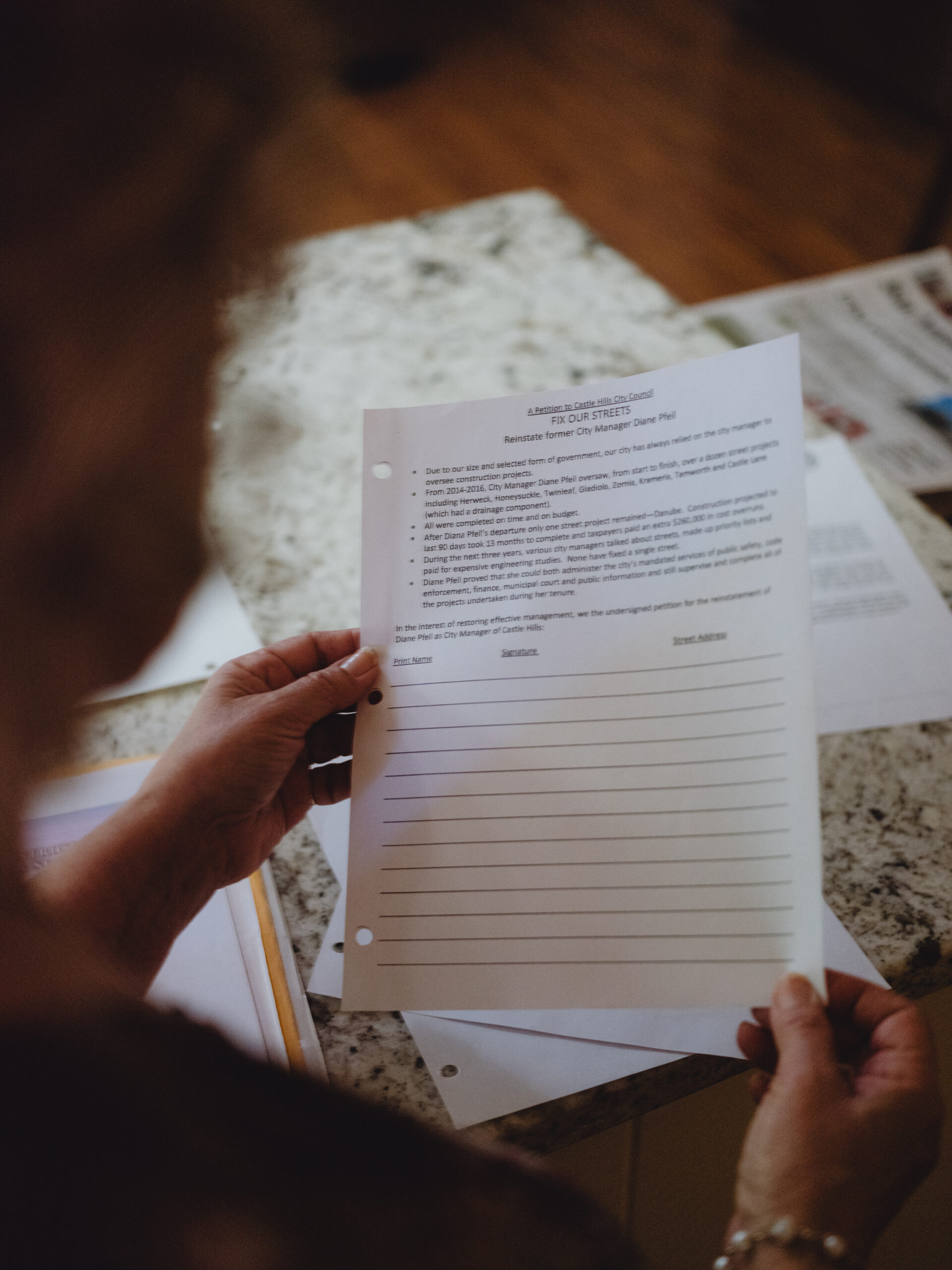

On the agenda of Gonzalez’ first council meeting on May 21, 2019, was Rapely’s performance review. In preparation, she’d circulated a nonbinding petition seeking his ouster, collecting 300 signatures.

In a testament to Castle Hills’ civic engagement, a crowd packed city hall. The rhetoric over the next three hours, however, could have been written by the creators of Parks and Recreation, the sitcom about an enthusiastic public servant constantly tested by indolent elected officials and irate residents. Critics yelled from the audience, and Gonzalez and Wenger bickered with constituents. One man took the microphone and shouted them down. Another person accused Gonzalez of asking her to sign the ouster petition “under false pretenses.” The debate dragged on so long that the council decided to delay the performance review a month and return the next afternoon to address the rest of its agenda.

When the meeting finally ended the following evening, Gonzalez picked up a stack of papers off the dais, put them in her binder, and stepped away. A video the city posted on its YouTube channel in December then shows Mayor Treviño returning to the dais and looking for something. He calls over a police officer, and they have a brief conversation. The officer walks away and returns with Gonzalez. She flips through her binder and hands a stack of papers to Wenger who immediately hands them to the city secretary.

Top city officials later described that exchange this way in an arrest warrant affidavit: Gonzalez panicked after being accused of obtaining signatures under false pretenses and tried to make off with the petition to cover her tracks. Security videos of Gonzalez “show several furtive movements,” according to the affidavit.

To these charges, Gonzalez offers a simple defense: She accidentally placed the petition in her binder. When the mayor asked, she promptly returned it. “I was surprised to see it there,” she said. “And he said, ‘You must have picked it up by accident.’… It was there [for] maybe five minutes.” (In an email following the publication of this story, Treviño wrote that Gonzalez picked up the petition prior to the meeting. A video of the incident posted on Castle Hills’ YouTube page does not have a time stamp.)

Two days later, Gonzalez and Wenger arrived at city hall for a meeting with Rapelye to review his personnel file, most of which is public information under state law. Rapelye had asked a police sergeant to attend the meeting. In the city’s version of events, Gonzalez drew the officer aside to distract him. Then, according to the arrest warrant, Rapelye saw Wenger writing down his social security number, driver’s license number, and birthdate, information that is usually exempt from disclosure under the Texas Public Information Act. When Rapelye confronted her, Wenger tore up her notes.

Wenger didn’t respond to requests for comment. But Gonzalez said Wenger wanted to run a background check on Rapelye, which Wenger believed as his employer she had a right to do.

That same day, Siemens, the police chief, told his sergeant to expect a complaint from the mayor about Gonzalez, according to a police report.

In June 2019, Siemens reached out to an unusual figure, asking him to take over the criminal investigation. Wright was a police officer in Hill Country Village, another incorporated enclave surrounded by San Antonio, from 1995 to 2000. Wright joined the Castle Hills Police Department as an unpaid reserve officer in 2004.

Wright is also an attorney who practices under his middle name, Wyatt. Anyone in Central or South Texas who’s been near a television in recent years has probably seen an advertisement for his father, Wayne Wright, also an attorney. Alexander Wyatt Wright works at his dad’s firm. Like any good litigator, he has a way with words.

“It was a shock, and it was scary. I hadn’t done anything wrong.

“I met with Ryan Rapelye to interview him and immediately noticed that this man appears nearly broken, mentally,” Wright later wrote in an affidavit. “The constant barrage of harassment from Lesley Wenger has created a toxic and hostile work environment for Mr. Rapelye. … But the situation turned even worse on May 24, 2019, when Lesley Wenger purposefully stole Mr. Rapelye’s ID INFO.”

Wright cast himself as an impartial investigator above the fray of Castle Hills politics. “I do not work alongside [Castle Hills Police Department] officers, I do not answer to them, I do not socialize with them, and, in fact, I don’t even know most of their names,” Wright wrote in a report. “Although this makes me unpopular, it is by design—so that when I am called upon it can’t be argued that I have allegiances to anyone, or anything, other than seeing that justice gets done.”

When Gonzalez arrived at city hall for the July 9, 2019, council meeting, she was approached by City Attorney Marc Schnall, who claimed that the Bexar County sheriff who administered her oath of office wasn’t authorized to do so, according to a lawsuit Gonzalez later filed. When she tried to participate in the July 17 council meeting, Schnall said her seat was vacant.

Unknown to Gonzalez, a state district judge found earlier that day that Wright had probable cause to arrest her and Wenger.

The next morning, Gonzalez got the frightening news. Her husband drove her to the Bexar County Adult Detention Center, where Gonzalez was handcuffed and led away. She and Wenger spent the day in custody. Anytime they tried to stand, they were ordered to sit, Gonzalez said. She was too scared to use the doorless toilet. “It was a shock, and it was scary,” she told the Observer through tears. “It was humiliating. And I hadn’t done anything wrong. That was such a dishonor to my family and my friends and myself.”

In early August, six Castle Hills residents described in Gonzalez’s court filings as “citizens with connections to the city,” filed a lawsuit to remove her and Wenger from office. The lawsuit alleged, among other things, that the two had violated the Texas Open Meetings Act. At the August 13 council meeting, Gonzalez said, she arrived to find the former council member she’d defeated in her seat.

It’s hardly unheard-of for small-town disputes to turn so nasty, said Louis Martinez, the San Antonio lawyer who represented Gonzalez in her criminal case. Martinez also represented a city council member in Leon Valley, yet another municipality within San Antonio, who was charged with assaulting a police chief he’d criticized.

In both the Castle Hills and Leon Valley cases, Bexar County prosecutors stepped in and dismissed the charges. The criminal cases against Gonzalez and Wenger were dropped in August 2019, and the district attorney’s office asked a judge to drop the city’s civil suit to remove them from office in January 2020.

But, by that point, Gonzalez was ready to give up. No longer believing she’d be effective, she relinquished her seat. “I thought to myself … ‘I’m being mistreated, and I don’t know when I’m going to jail again,’” she said.

Then, lawyers with the Institute for Justice, a libertarian-leaning public interest law firm, reached out: If she was arrested in retaliation for collecting petition signatures and for criticizing the city manager, they suggested, her First Amendment rights had been violated.

In September 2020, Gonzalez sued Castle Hills and the mayor, police chief, and special detective, alleging that her “arrest was unlawful because it was engineered and executed … to retaliate against [her] exercise of political speech.”

The intimidation campaign worked, her lawyers argued.

“Sylvia, with her reputation ruined and her pocketbook significantly diminished, has been so traumatized by the experience that she will never again help organize a petition or participate in any other public expression of her political speech,” they wrote in the lawsuit. “She also will never again run for any political office.”

In court, the city’s lawyers argued that everything the mayor, police chief, and special detective had done was in good faith. Gonzalez’s “arrest was as a result of a warrant issued by … a Bexar County District Court Judge who made an independent determination,” the attorneys wrote in a motion to dismiss.

But Castle Hills officials’ handling of the investigation belies their claims, Gonzalez’s lawyers responded. Wright, they allege, is a friend of Siemens. The affidavit Wright swore out makes much of Gonzalez’s criticism of the city manager, which Gonzalez’s lawyers say proves her arrest was directly tied to her speech. They allege Wright took steps to ensure she spent time in jail, including by going directly to a judge and bypassing the Bexar County district attorney, who would have likely refused to bring charges.

Gonzalez faced an uphill battle in court: In cases alleging retaliatory arrest, judges often defer to police judgments regarding probable cause and rarely allow lawsuits against officials to proceed. But two months before Gonzalez’s arrest, the U.S. Supreme Court created a narrow avenue for such lawsuits in a case called Nieves, after an Alaska state trooper who referred to a man’s comments about police while arresting him for disorderly conduct. In Nieves, the court said that even police who have probable cause to make an arrest can be sued if a plaintiff presents “objective evidence” that “similarly situated individuals not engaged in the same sort of protected speech had not been [arrested].”

In order to bolster their allegations to meet the standard set in Nieves, Gonzalez’s attorneys researched how many other people had been arrested for tampering with a government record. They found that most people charged with breaking that particular law in Bexar County in the previous decade had used or made a fake document, like a driver’s license, social security card, or green card.

“After this month-long investigation, the only charge … Wright could bring was one misdemeanor that has never been brought against someone for even remotely similar conduct, and certainly not against someone for stealing their own petition,” the lawyers wrote.

In Gonzalez’s case, a U.S. District judge in San Antonio found that Gonzalez had enough evidence of being improperly singled out that her case could proceed. The city officials then appealed to the Fifth Circuit.

Two of the three Fifth Circuit judges who reviewed her case decided to effectively neuter the Supreme Court’s holding—breaking with a pair of other federal appeals courts in the process. Gonzalez couldn’t rely on statistical evidence, the judges said—she’d need to find someone else who’d done something similar but hadn’t been arrested. First Amendment advocates say the ruling is so narrow it could be interpreted to require Gonzalez to find another elected official who’d taken government paperwork but wasn’t arrested.

The panel’s third judge, Andrew Oldham, a former general counsel for Governor Greg Abbott, disagreed, saying that a group of officials using an investigation to target a city council member shouldn’t receive the same benefit of the doubt that a street cop might if he made an improper spur-of-the-moment arrest. “It’s unclear to me why we should apply a rule designed for split-second warrantless arrests to a deliberative, premeditated, weeks-long conspiracy,” Oldham wrote in his dissent.

The rest of the Fifth Circuit refused to hear Gonzalez’s appeal, so she went to the Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments in March. There, Gonzalez’s lawyers argued that in cases where officials have time to get a warrant, courts should hold them to a higher standard. They should use a different precedent that permits lawsuits against city governments if the plaintiff shows the government had “an official retaliatory policy.”

The lengths Castle Hills officials went to force Gonzalez out of office show they had a retaliatory policy, her lawyers argued. If the Supreme Court sanctions this argument, it would set a new legal precedent that would more clearly empower people targeted in retaliatory arrests to sue individual government officials.

A dozen organizations from across the political spectrum filed briefs supporting Gonzalez. With so many obscure laws on the books, petulant government officials can come up with a reason to arrest just about any critic, they argue. One of their common themes is, as the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation put it, “the sheer difficulty of living a probable cause-free lifestyle.”

But the city’s lawyers argue that a ruling that favors Gonzalez could create “a chilling effect on public officials who report criminal activity.” Police officers “would have to make a determination as to whether the report of a crime is in retaliation for First Amendment speech,” they wrote. In this argument, they’re supported by a coalition of government groups including the National League of Cities and the state governments of Alaska and Texas.

During oral arguments, most of the justices’ questions focused on exactly how plaintiffs can establish that they were truly singled out for arrest because of their political viewpoint or speech. Does a plaintiff need to find someone who engaged in the exact same behavior and wasn’t arrested? Should the standard be different for misdemeanors than felonies? What if someone committed an obscure crime for which no one had ever before been charged? Does it matter if, in Gonzalez’s specific case, she took the petition on purpose or by accident? Should the circumstances surrounding the arrest—such as Gonzalez’s allegation Wright used an unusual procedure to make sure she went to jail—factor in?

“Political retaliation is dangerous,” Bidwell told the justices. “The First Amendment has to mean something.”

Lisa Blatt, the seasoned Supreme Court practitioner representing Castle Hills, responded that officials should only be liable in very limited circumstances: specifically “for warrantless arrest where officers typically look away or give warnings or tickets.” She cited a journalist singled out for arrest while covering a protest as a classic example. The fact a judge signed off on a warrant should provide more protection for government officials, not less, Blatt argued.

Bidwell responded that under such a narrow exception, someone like Gonzalez wouldn’t be able to sue even “if the mayor in this case got in front of TV cameras and announced that he was going to have Ms. Gonzalez arrested because she challenged his authority.”

Even if the justices merely clarify that the Fifth Circuit’s holding was too restrictive, “We still think that could go a long way toward preventing some of the abuses we’re most worried about,” Grayson Clary, a staff attorney for the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, told the Observer. A less restrictive interpretation of Nieves might, for example, create a path forward for the lawsuit against Laredo and Webb County officials by Priscilla Villarreal, the Laredo citizen journalist known as La Gordiloca. As the Observer reported earlier this year, Villarreal’s lawyers allege that local officials dug up another rarely used statute and applied it in a way no one else had before: They arrested her for using information from a police source to break news about a death. In January, the Fifth Circuit ruled against Villarreal.

Back in Castle Hills, the debate is less about the lawsuit’s national implications and more about what it means for local taxpayers. To assuage concerns, Mayor Treviño wrote in a January newsletter that the city’s insurance would cover legal bills.

Politics is much less interesting in Castle Hills these days. During a February meeting, city hall was almost empty. The council finished its agenda in barely an hour. Gonzalez says that’s not such a good thing.

“Everybody’s afraid,” she said. “What they did to me froze everybody else out. What happened to me will happen to you. It’s a very loud message to everyone.”

Last year, Treviño and another council member ran for reelection unopposed. Three other members’ terms end in May. But since none drew an opponent, the city canceled this year’s election.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified to whom Sylvia Gonzalez handed the petitions after the May 22, 2019, city council meeting. Gonzalez handed them to Lesley Wenger, who handed them to the city secretary.