Gunfire jolted Zoey Sanchez awake that night in February, not something she heard often in her usually tranquil neighborhood in Plano, north of Dallas. Then she heard screeching tires. After a few minutes, Sanchez peeked out a window to see police officers detaining a young woman.

Sanchez eventually went back to sleep. Then it was sunrise, and her husband was jostling her awake. You need to get up, he said. There’s drama. She grabbed a bathrobe and walked out of the front door—and into chaos.

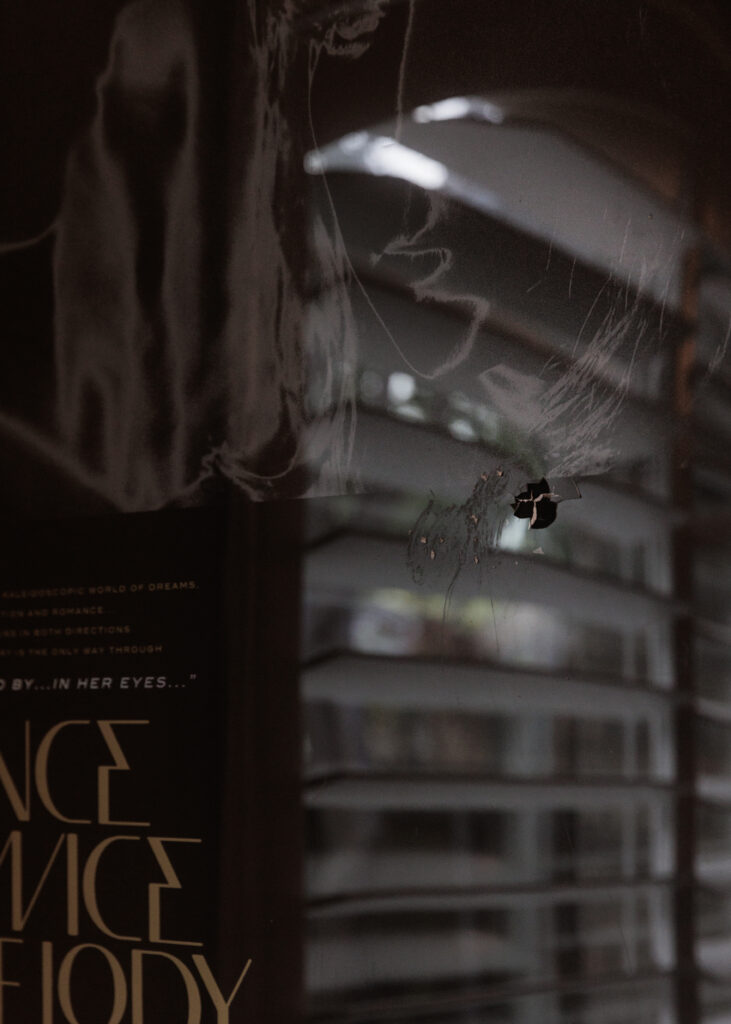

Outside, news crews and upset neighbors had descended on remnants of an active crime scene. And everyone seemed to be looking at her house—specifically, at a window in her young daughter’s playroom. She learned that a party at the short-term rental house across the street had turned into a gunfight, and one bullet had ricocheted around her daughter Luna’s playroom, crossing the nook where Luna likes to read. Thankfully, Luna had been asleep in her bedroom, tucked away from windows facing the street.

The two-story brick rental house had become a frequent source of trouble for the neighborhood Sanchez loved. An outsider had bought it, sunk a lot of money into it, tried to sell it, and then turned it into a bed-and-breakfast. For months, loud tenants and their guests had disrupted the street. Neighbors had seen partygoers peeing in the yard, hanging out of windows, and screaming. Their cars filled the block. To neighbors, police had seemed unable, and the owner unwilling, to address the stream of complaints. Now the partying had escalated to violence that could easily have killed Sanchez’s daughter.

Shootings, with horrific consequences, have become almost commonplace at Texas schools, houses of worship, restaurants, shopping malls, and concerts. This time, Sanchez feared she’d have to explain to Luna that she might not even be safe from gunfire in her own home.

“As a mom, you don’t care about yourself. But your biggest thing is, you want to have your kids safe,” said Sanchez, an occupational therapist. “So when your house is not safe anymore, you’re like, ‘Well, that sucks. I failed.’”

Your biggest thing is, you want to have your kids safe. So when your house is not safe anymore, you’re like, ‘Well, that sucks. I failed.’

When Sanchez began researching the situation, she found that the problems at B&Bs in other neighborhoods were equally serious. The previous fall, police busted a sex trafficking ring operating a brothel out of a short-term rental three miles away. In nearby Wylie, a woman allegedly used an Airbnb in fall 2021 for sex trafficking her 8-year-old daughter. In northwest Dallas, according to news reports, an Airbnb unit owner fired his management company after neighbors complained about visitors and armed security guards.

What had once been a way for visitors to find charming, off-the-beaten-path lodgings—and a way for local property owners to make extra money with little neighborhood disruption—has become a global business dominated by corporate investors that in many places threaten the safety and character of residential neighborhoods. How short-term rentals (or STRs) fit into the local landscape varies, but it’s becoming universally accepted that, left uncontrolled, their impact can be immense. In some places, they are making rental housing so lucrative as tourist lodging that it is becoming unavailable and unaffordable to local workers, students, and other residents. Selling for higher prices, they drive up property values and neighborhood tax bills and replace families with a steady stream of strangers—whom locals see as producing more crime and less accountability than traditional renters.

Neighborhoods tend to be—or used to be—a strong force in Texas politics. Often, angry neighbors’ comments have been loud enough to kill off affordable housing or commercial developments. But short-term rental companies with highly paid lobbyists, worldwide reach, the offer of hotel-tax millions to local and state governments, and the support of local B&B owners and operators, are a formidable force. Cities around Texas and the world, from San Juan to Taipei to Barcelona, are scrambling to address resulting problems.

Some neighborhoods in Fredericksburg appear deserted during the week because so much housing is aimed at weekend guests—while the popular tourist town has a labor shortage because of the lack of affordable housing. In Galveston, short-term rentals are worsening the lack of housing for working-class and middle-class residents. In Arlington and Fort Worth, residents fought for regulatory measures, with threats of lawsuits always in the air. In Dallas, it took four years for a strong neighborhoods coalition to win city council approval of an ordinance banning such rentals from single-family residential areas.

“We stand together, although there were more of us earlier today, and we represent about 500,000 other homeowners, and there are renters too, who unfathomably find ourselves as the underdog in this fight,” said Olive Talley, one of the leaders of the fight against short-term rentals in Dallas, a few hours before the city council passed the ordinance.

In the meantime, B&B corporations have crafted deals to pay hotel taxes on behalf of rental property owners to the state and some cities. For individual owners, those deals help shield them from state scrutiny over how much they should be paying in taxes and being identified as short-term rentals for tax and zoning purposes. At the same time, they provide the kind of income to states that engenders a lot of goodwill. Since May 2017, Airbnb, one of the largest companies, has paid Texas more than $229 million, and HomeAway has paid more than $57 million, according to the state comptroller’s office.

Bills to prevent cities from regulating short-term rentals have been filed—and thus far defeated—in the Texas Legislature repeatedly since 2017 and likely will be filed again.

For now, city councils continue to struggle to pass rules that can pass muster in expensive court challenges, where by a slight margin, rental property owners are ahead. The result has been a patchwork of partially enforced regulations, dwindling housing stock, and, in some cities, the continuing degradation of neighborhoods.

In 1995, a retired teacher started a website to rent out his Colorado ski resort condo. Five years later, Vacation Rental By Owner, or VRBO, was advertising properties in all 50 U.S. states and 28 countries. Then, in 2005, venture capitalists in Austin started a company called HomeAway with six employees who quickly bought up similar companies. Within two years, HomeAway raised $160 million and bought VRBO. The combined company, called VRBO, operated more than 130,000 properties in almost 100 countries. It had no real competition until a new San Francisco-based website called Airbed and Breakfast officially launched at South By Southwest in Austin in 2008. Built with less than $20,000, the website helped hundreds of people find accommodations in places where hotels were already sold out—in Denver, for instance, for the Democratic National Convention.

Bed-and-breakfasts were already popular in Fredericksburg by the 1990s. They were mostly the kinds of places where hosts fixed breakfast for visitors, and owners often lived onsite. A few reservation services popped up to help manage bookings at hundreds of such lodgings.

That picture changed by the new millennium, with VRBO going strong and Airbnb newly launched. Homeowners like Austin’s Sharon Walker were getting involved. She and her husband were in trouble on the mortgage on their dream home downtown. They had to sell it or figure something out.

“We’d heard about this company, HomeAway. I contacted all of the five listings that were there at the time for Austin, and one woman took the time to talk to me,” Walker said. “She said it was successful.”

Walker and her husband moved across the street and put their house up for short-term rental on HomeAway. In 2010, Walker rented her house for $500 a night, almost every weekend, and watched through the kitchen window as visitors checked in across the street. She learned to avoid problems by asking potential guests about the nature of their trips and groups. At first, she thought of it as “not a business” because it was “still the residential use of a home.”

The next year, prior to SXSW, Walker heard from desperate Google and Apple executives who’d found local hotels sold out. Walker emailed 30 friends to see if they’d host people in their homes and got 15 yeses. She coordinated the guests’ stays as a festival rental manager. The next year, she rented out 150 houses for SXSW. By 2012, Walker’s management gig had become a business.

While the lodgings offered by Walker and other “hosts” on HomeAway and Airbnb were becoming popular, they were also attracting the attention of cities. In 2011, the Austin City Council, alerted to the tax income potential of short-term rentals, approved a study. They found that, while some operators had been paying hotel occupancy taxes—money traditionally used to promote tourism—only 80 of 200 originally identified short-term rentals were paying it. And then an audit found that the number of units was closer to 1,500.

Kathie Tovo, then a council member and a strong opponent of short-term rentals in residential neighborhoods, said that opposition to a proposed ordinance usually comes from owners who have only one or two rental properties. But as the city accumulated information, she told the Texas Observer, “More often it looked like … people were making their living this way—you know, they were acquiring four or five properties.”

More often it looked like … people were making their living this way—you know, they were acquiring four or five properties.

The following year, Austin passed the first ordinance in Texas regulating short-term rentals, requiring them to register, pass inspection, and pay hotel taxes and other fees. But—as is usually true with most issues regarding that industry—it wasn’t that simple. Entering new territory, city leaders amended the ordinance, redefined allowable rentals, and got sued. By 2017, Austin’s ordinance allowed the city to deny licenses to new short-term rentals in residential zones if they are not owner-occupied properties. Properties already being used as short-term rentals, even if not owner-occupied, were grandfathered in.

Tovo said the council was concerned about the availability of affordable housing and the effects of short-term rentals on school enrollment. It was easy to see why short-term rentals would reduce the housing available on longer-term leases, she said. “You’re gonna make more money as a short-term rental.”

Walker’s short-term rental business helped her and her husband keep their dream home, and she felt that she had served a real need for lodging in Austin. Working only with owner-occupied properties, which might only be rented out a few times a year, “doesn’t work for us” as a sustainable business, she said. She still manages about 30 non-owner-occupied rentals in Central Texas. She thinks opponents are blaming short-term rentals for too many problems and using fear of crime as a weapon.

Short-term rentals seem here to stay. They fill a need. Many of the owners pay taxes and are responsible hosts. But problems linger. Industry representatives like to focus on how much money their business brings in, how ordinances hamper property rights, and blame “party houses” and crime on a few bad actors while touting improved safety and accountability processes like background checks. But it doesn’t take many bullets through a little girl’s playroom window, or busts of drug operations and prostitution rings, for residents to see what might happen in any neighborhood if short-term rentals go unregulated.

In 2013, Jeryl Hoover was in his second term as mayor of Fredericksburg (he’s now in his third) when residents approached him with the idea of changing the town’s bed-and-breakfast ordinance to allow them in single-family residential neighborhoods. He agreed.

“I bear this scar,” Hoover said. Residents were having a tough time getting (or paying for) mortgages. “So we thought, well, maybe more people could buy an R1 [single-family] house if part of their mortgage affordability plan was to operate a B&B, either in their home or in an accessory building out in the backyard.”

From that came what Hoover calls a “tsunami of growth,” but it wasn’t the kind that helped most residents. Now, local workers can’t find homes to rent long-term. Nor can they afford to buy homes—but wealthy investors, often from out of town, can. For eight years, no new hotels were built, while the numbers of short-term rental units skyrocketed. In 2020, taxes paid to the city by STR operators surpassed tax income from traditional hotels and motels. More than 1,900 short-term units now comprise nearly 25 percent of the town’s housing inventory.

More than 1,900 short-term units now comprise nearly 25 percent of Fredericksburg’s housing inventory.

“The problem we have here is as our visitor numbers continue to increase, we don’t have enough support structure,” said Tim Lehmberg, executive director of the Gillespie County Economic Development Commission. “We have a severe labor challenge here that’s driven by a number of things, but primarily [by] such an extraordinarily high cost of real estate.”

The city hasn’t ignored the problem: Regulations have been put in place and amended. Now, short-term rentals must get permits and pass inspection. Certain types of new STRs are limited in single-family zoned areas. In June, Hoover and the council were revisiting the rules again to help locals get back into single-family homes and to protect neighborhoods—though that effort may be too late. Finally, at least 800 new hotel rooms are on the five-year horizon.

While many want the council to control the short-term tidal wave, those benefiting from the industry like things just the way they are. According to Airbnb, its hosts in Gillespie County made $40 million in 2021.

Matt Durrette, owner of a Fredericksburg-based short-term rental management company, wrote to city officials about proposed changes, noting that tourism is the largest employer in town. “Innovative solutions” to long-term housing would be better than “stripping away people’s rights” and … [blaming] STRs,” he wrote.

Outside of the United States, the story is often the same: Short-term rentals are blamed for housing shortages in places like Amsterdam, which has strict limits on vacation rentals; Barcelona, which banned short-term private room rentals in 2021; and the entire country of Portugal, which is no longer issuing new licenses for short-term rentals.

The short-term rental industry denies that its growth is part of such problems. A 2019 national study paid for by VRBO (now Vrbo) concluded that other factors, like rising household income, were to blame.

Other studies produced different results. A year after the VRBO study, a community activist who created a data project called Inside Airbnb collaborated on a study with a left-wing group in the European Parliament and concluded, “With case studies on Barcelona, Berlin, Amsterdam, Paris, Prague, Vienna, New York and San Francisco, the report reveals how Airbnb has driven up rents, caused damage to urban communities, and wrecked affordable social housing programmes.”

Problems with vacation rentals don’t happen only in tourist towns. Take Plano, for example. Now home to about 300,000 people, parts of the city were still farmland in the 1980s, when Ross Perot bought 2,700 acres and moved EDS, his multinational information technology company, to town. Various corporate headquarters followed.

In spring 2019, Plano became the first Texas city to sign a hotel-tax collection agreement with Airbnb. Officials touted the new revenue stream. Last year, Airbnb and Vrbo together paid Plano nearly $600,000 in hotel taxes.

But by November 2019, it was impossible to live in Plano and not know that STRs posed problems. Late one night, teenagers crashed a party at an Airbnb, got kicked out, and retaliated by allegedly shooting into the home. Marquel Ellis Jr., 16, an Allen High School sophomore and football standout, was killed.

“It was literally rented as a party house,” said Plano City Council member Shelby Williams. “East Plano is not a vacation destination.”

It is, however, an affluent city with plenty of large homes, many with pools—the perfect locations for family reunions, bachelor trips—and parties. After Ellis was killed, residents showed up again and again at city hall to describe what it was like to live next to such houses.

“Honestly, it had not come across my radar before,” Williams said. “After that, it registered in a big way. At the time and now … I feel a responsibility.”

Things were quiet for a while—the pandemic pushed other items off the nightly news. Then came the brothel bust, then the shooting across from Zoey Sanchez’s house. Residents and council members were reenergized. Williams said he heard from the Texas Neighborhood Coalition’s local chapter at almost every council meeting for months. “We had a core group of eight to 10 people, and every week, we’d go to city council and talk about it,” chapter leader Bill France said.

The Plano City Council in fall 2022 asked staff to work on a short-term rental registration program and commissioned a survey. Nearly three-fourths of respondents said they would be moderately or very uncomfortable living on the same block as an STR. More than a third of those with personal experience with the rentals reported safety or noise concerns. In May, the council voted to ban all new STRs for one year so the city could study their implications and appointed a citizen task force to examine the issue.

The brothel bust and the shootings personalized the crime problem for Plano citizens. Industry supporters question the accuracy of studies showing that violent crime rates rise because of short-term rentals, but statistics pale beside residents’ outrage over specific incidents.

The industry says the instances are statistically rare—plus, Airbnb banned parties in 2020. But activists have built a national database to show that shootings, at least, aren’t all that rare.

Cities have plenty of incentive to work out compromises with the bed-and-breakfast industry. In Austin alone, Airbnb officials estimated that a tax collection agreement between Airbnb and the city would produce $15 million to $20 million annually in hotel tax income. Airbnb has tax-collection agreements in 15 other countries and territories and in nearly every U.S. state. In Texas, the company has agreements with the state, about a dozen cities, and a few counties.

The agreements mean that, rather than hotel occupancy taxes being paid by the individuals who rent their properties on Airbnb or Vrbo, the companies pay on behalf of all their bookings in the area. Typically, the amounts paid under the “voluntary collection agreements” are much larger than what had been coming in from individual property owners.

But, as the hotel industry and the Economic Policy Institute have pointed out, the agreements conceal specifics on how many and where vacation rentals are actually operating. Typically, cities can audit information the companies provide, but not information from individual property owners. Such agreements have drawn a caution from the National League of Cities, which says some officials worry that the agreements allow the companies to pay less than they owe and make auditing impossible, as was the case in New Orleans in 2021.

The agreements stipulate that the companies will pay the taxing jurisdiction’s hotel occupancy tax rate—in Plano’s case, 7 percent—on “taxable booking transactions.” The companies self-report the taxable amount and pay the taxes they presume they owe, just as with retail sales taxes. Expedia did not respond to multiple requests for comment about its agreements. According to Airbnb, they are “happy to work with cities” that want more detailed information.

Instead, municipalities pay thousands of dollars for software to comb through the short-term rental platforms and find properties that operate illegally—without a permit or in a zone where they are outlawed.

Overall, the platforms are enormous. Airbnb’s initial public offering was the biggest in the country in 2020. Aside from a slight dip in 2020, the company’s taxable receipts in Texas have skyrocketed, going from $143.8 million in 2017 to over $1 billion in 2022. HomeAway’s taxable receipts rose from $100 million in 2019 to just under $300 million in 2022.

The timing of those agreements has coincided with the Texas Legislature’s attempts to protect companies from local regulation. The tax collection agreements were made possible by a 2015 law. In 2017, the state entered into its agreement with Airbnb to collect its share of hotel taxes directly from the platform. Simultaneously, lawmakers drafted their first effort at preemption—a bill that would have kept municipalities from banning short-term rentals.

Tourism is big business in Arlington, home to the Texas Rangers, the Dallas Cowboys, the original Six Flags Over Texas amusement park, and a growing entertainment district. Billions of dollars have been invested, and millions of tourists—and their dollars—arrive annually. David Schwarte, a former corporate lawyer for American Airlines and a tech company, lives not far from the giant AT&T Stadium where the Cowboys play. One day his neighbor told him that a property owner had just “opened up the short-term rental from Hades” nearby. In fact, he said, five of about 80 area homes were being rented short-term, often to people throwing parties. Kids were learning dirty words from loud partygoers. “It was a total mess,” Schwarte said.

He and others in the neighborhood formed an alliance and started to research. They studied other cities’ dealings with STRs and spoke often at city council meetings, detailing what it was like to live next to a so-called party house. For more than two years, the council studied the issue before adopting restrictions.

In April 2019, Arlington passed an ordinance to create an STR zone, extending about a mile beyond the borders of the entertainment district. Short-term rentals are allowed inside the zone and in areas zoned for mixed uses, but they’re forbidden in single-family residential neighborhoods. Another ordinance was passed to regulate the operation of such rentals.

Five STR owners sued, saying the ordinances violated their rights. The courts upheld the ordinances. Arlington had shown that short-term rentals could disrupt residential neighborhoods, so restricting them was legal, the appellate court said, and the city had also worked to reach a consensus in the community. The “Arlington model” was born, but what made it successful was the fact that the city’s development code had never allowed residential property to be used for rentals shorter than 30 days. As in other cities, the ordinances didn’t solve all the problems: Officials estimate that hundreds of units are operating without licenses.

Just west of Arlington, Fort Worth passed its ordinance regulating short-term rentals in February. Like Arlington, the larger city had never allowed short-stay rentals in its rules for residential districts. After the ordinance passed, some rental operators registered with the city and paid the required fees while others closed. But the elephant in the room is the 600 or so rental units that have been picked up by the city’s software as apparently operating in illegal zones. For now, said Shannon Elder, the city’s assistant director of code enforcement, she and her staff are focusing on properties that have generated complaints.

Fort Worth neighborhood groups, meanwhile, were keeping a close eye on what was happening in the Legislature. And down the road in Dallas, where a long fight was coming to a head, activists were watching what happened in Fort Worth.

In Dallas, the fight over short-term rentals in neighborhoods took four years of sometimes bitter debate—and the city is still likely to get sued.

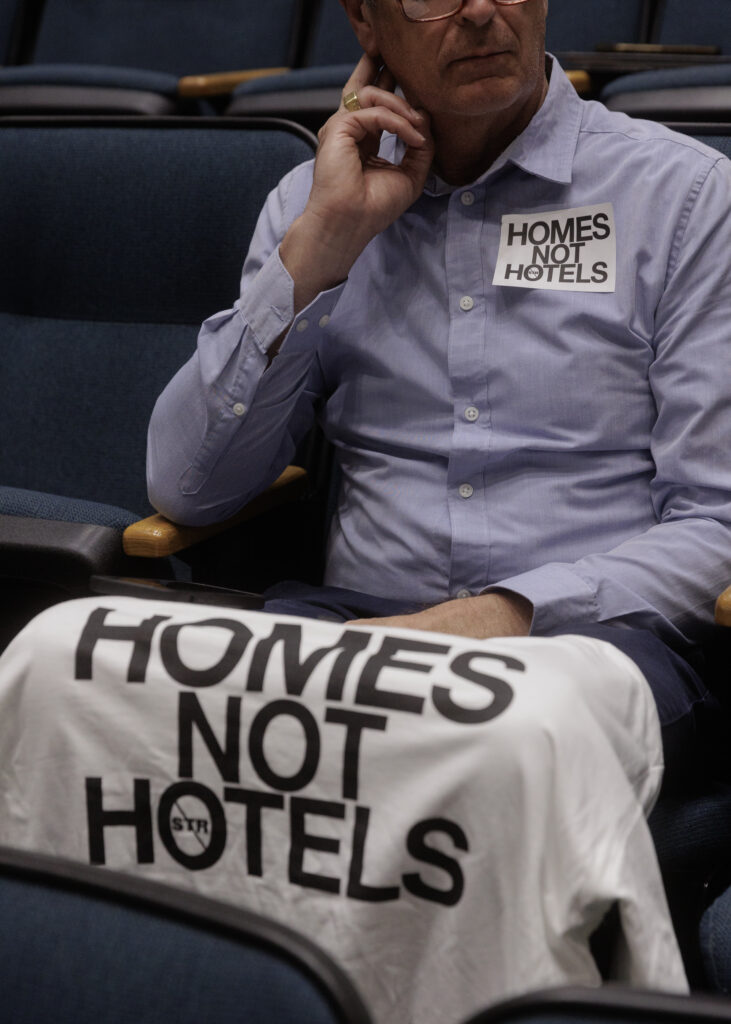

In June, just weeks before a council vote on the proposed ordinance, a long, noisy party at an STR in a quiet neighborhood ended in gunfire, terrifying residents. As has been the case in other areas, the incident inspired a new set of neighbors to post “HOMES NOT HOTELS” signs in their yards and show up at city hall in t-shirts with matching slogans. This time, photographer Sonya Herbert was among them, roused to action by the raucous party two doors down from her home. She’d brought along a video she took showing teenagers partying in the street and, eventually, the gunfire.

“You can’t see [in that video] the fear and confusion my two daughters experienced and are still experiencing, having been woken up by machine gun fire less than 40 steps from their home. How would all of you feel if this were happening in front of your home?” Herbert told council members.

Lisa Sievers, an STR owner active in the Dallas Short Term Rental Alliance, said the anecdotal stories about crime are misleading since they could take place anywhere. “We’ve had people shoot into people’s houses on my street, and we have a park across the way where drug deals go on all the time,” Sievers told the Observer.

For documentary filmmaker Olive Talley, the fight came to her street near Lakewood, in East Dallas, via a house listed as “Your Own Private Dallas Oasis” on STR platforms due to its three-story cabana overlooking the backyard swimming pool. There were also parking issues, but the noise really got to her.

“Just imagine people rolling roll-aboard suitcases up and down the sidewalk at all hours of the day and night … people partying outside,” she said. “I have video of one group, and they’re throwing balls off the cabana at each other down below, and each one [gets] a cheer. This goes on until 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning. … You know, we often wonder if any of the owners of STRs would enjoy having an STR like this … right next door to them. I would venture to say most of them would say ‘no.’”

I have video of one group, and they’re throwing balls off the cabana at each other down below, and each one [gets] a cheer. This goes on until 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning.

She discovered the Texas Neighborhood Coalition, which helped her find allies and learn about court cases and similar fights around the country. In May 2021, about a hundred people signed up to speak publicly on the issue at a city council meeting. That meeting “helped a few of us get in touch with each other. Oh my gosh, this is happening in South Dallas. This is happening in Oak Cliff. Oh my gosh, this is happening in District 3 and District 4,” Talley said.

As their group grew, the city held meeting after meeting with task forces, committees, and the full council as they batted around potential definitions and regulations. Finally, in June, the council was set to vote on an ordinance that would ban new STRs from single-family neighborhoods and establish new registration requirements. Once more, neighborhood advocates donned white “HOMES NOT HOTELS” t-shirts and waited their turn at the microphone. Both sides had shown up in force. Talley was one of the first of about 60 to speak.

“You can vote to protect homes and neighborhoods, or you can vote to destroy neighborhoods as we know them and worsen your housing crisis,” she said. She motioned to the crowd of supporters behind her to rise.

Council member Adam Bazaldua warned that an outright ban could make the city vulnerable to litigation and put a target on Dallas’ back in the next legislative session. “We need to give the residents as much relief as we can while still protecting the city’s best interest,” he said.

As the night wore on, it was clear that neighborhood advocates had the votes they needed. The ordinance was adopted. The city’s goal is that, beginning in December, short-term rentals will be banned from single-family neighborhoods and limited in multifamily residential zones.

Sievers said she is waiting to see what happens before making changes to her operations. “It was disappointing that the city council elected to put thousands of entrepreneurs out of business, that they elected to put millions of enforcement dollars on the backs of the taxpayers of the city,” Sievers said. “This is going to end up in a big fat lawsuit.”

Sievers is probably right about the lawsuit. Court fights over short-term rental ordinances continue to shape the debate. One was filed just a day after Dallas’ ordinance passed—but it was over the Fort Worth ordinance.

Graigory Fancher is representing the 113 Fort Worth property-owner plaintiffs. “We’re saying that it’s not constitutional to take away that property right from homeowners,” he said. If his clients win, “it’s going to be the roadmap to overturn all of the other ordinances in all of the other municipalities.” City officials, in a statement, said their approach “balances the preservation of neighborhoods and support of tourism” and that they would vigorously defend the ordinance.

In Austin, just down the street from city hall, the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF), representing a group of homeowners, challenged that city’s short-term rental ordinance on constitutional grounds. Attorney General Ken Paxton joined in, penning a 102-page brief. A state appeals court sided with TPPF in the case of homeowners who were already renting out their property before the ordinance passed. So STRs in operation before the Austin ordinance changed, even though they were not owner-occupied and were in residential zones, would be grandfathered in. But, according to the city, the court decision “does not require the city to issue new licenses” for non-owner-occupied homes.

TPPF Executive Director Rob Henneke disagrees. “Cities are ignoring adverse legal outcomes,” he said.

In August, a federal judge dealt another blow to Austin’s ordinance, overturning it, at least for now. It’s unclear how Austin will respond. Meanwhile, the pro-business Legislature and its members continue attempts to stop cities from banning short-term rentals.

State Representative Gary Gates, a Republican from Richmond, sponsored the latest preemption bill and will likely carry it again in 2025. He said publicly that he was interested because, as a triathlete with 13 children, he often relied on short-term rentals when the family traveled for his races.

When asked by the Observer who brought him the preemption bill, Gates said, “The industry kind of brought it to me—the short-term rental, the Airbnb industry.” Now, he has “developed a passion for this legislation,” he said. “I bought into that mantra of ‘local control’ until you start becoming the victims of overregulation.”

Short-term rental ordinances potentially could be affected by the state’s so-called Death Star bill, which went into effect September 1. It wipes out local control of many areas of law, but its wording is so vague and its enforcement mechanisms so uncertain that no one knows what the on-the-ground results will be. The bill’s authors have said it will not affect cities’ zoning powers or short-term rentals.

For people like Sonya Herbert in Dallas, more local action is necessary.

“If our communities can’t be safe just so investors from outside of Dallas can make a buck, that doesn’t make any sense,” Herbert said. “They should be protecting us, not the interest of the investors.”