She’s 28. She’s an Immigrant. She’s in Charge of Texas’ Most Populous County. Get Used to It.

When Lina Hidalgo was elected Harris County judge in November, many scoffed at her unexpected victory. Now she’s on a mission to prove that her progressive agenda is just what Houston needs.

When Lina Hidalgo was elected Harris County judge in November, many scoffed at her unexpected victory. Now she’s on a mission to prove that her progressive agenda is just what Houston needs.

*

by Blake Paterson

April 3, 2019

Simon Cruz timidly approached the lectern at the March 12 meeting of the Harris County Commissioners Court. The 79-year-old resident of Park Place, a predominantly Hispanic subdivision near Hobby Airport in southeast Houston, nervously introduced himself and told the court he was worried. He’d lived in the area for more than five decades, and now he was afraid the addition of a new development nearby would cause his home to flood when the next big storm struck. His testimony was followed by that of a neighbor, an environmental advocate from the Sierra Club, and a half-dozen others interested in flood control issues, totaling nearly an hour.

Just a few months earlier, such a banal scene — residents and stakeholders testifying before local government and receiving immediate feedback from elected officials — would have been unusual for the commissioners court. For decades, the twice-monthly meetings rarely ran longer than an hour and a half, and only a handful of citizens got the chance to speak. Now, the meetings have ballooned into seven- or eight-hour affairs.

That’s the doing of Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo, a 28-year-old political newcomer whose unexpected victory in November put her in charge of governing Texas’ most populous county. Her election solidified a progressive majority on the five-member governing body. She’s pledged to build a “county that works for everyone,” and, three months into her term, she hasn’t wasted any time getting started. One of her first motions after taking office in January was rescinding a rule limiting public input on a given issue to 15 minutes.

“She was definitely underestimated. She’s young, she’s brown and she’s a she.”

Hidalgo is responsible for a portfolio few millennials can rival. Despite its name, the county judge is an executive — not judicial — position, overseeing a payroll of nearly 18,000 people, a burgeoning population of more than 4 million and a $4.8 billion budget. If that isn’t enough, Hidalgo is now also the county’s director of emergency management, responsible for guiding the region through floods and superstorms like Hurricane Harvey.

Few expected Hidalgo to unseat Ed Emmett, a popular, moderate Republican who was widely regarded as a highly effective steward and one of the powerhouses of Houston politics. Just 15 months before winning the election, Hidalgo moved back home to Houston from Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she’d been living for the past year working on a graduate degree at Harvard, to take on Emmett.

Though the Senate race between Beto O’Rourke and Ted Cruz dominated headlines, Harris County turning solidly blue was arguably the biggest news of the night. And Hidalgo — a young, progressive, Hispanic immigrant — is now the face of this ostensible New Houston.

But many Houstonians greeted their new county judge with skepticism. Few in the county’s traditional political establishment lined up behind Hidalgo as a candidate, and many downplayed her victory. “Lina won on a Beto-driven wave of straight-ticket voting,” said Paul Simpson, the chair of the Harris County Republican Party. “I didn’t think the county judge was an entry-level position,” he added sarcastically.

She’s certainly an unconventional pick to lead the nation’s third-largest county. She’s never held political office and hadn’t attended a commissioners court hearing before being elected. In one debate, Hidalgo couldn’t name the county auditor. She entered office with dozens of critics who were wary of her inexperience and dubious of her knowledge of the limitations of the job.

Her supporters counter that she’s been prejudged by those who can’t see past her age, gender and ethnicity. After Hidalgo gave a press conference in both Spanish and English, Mark Tice, a commissioner in neighboring Chambers County, wrote online, “English this is not Mexico,” later telling the Houston Chronicle “This is the United States. Speak English,” and calling Hidalgo a “joke.” When pressed, Tice couldn’t explain why Hidalgo was unqualified. “I don’t have [her résumé] in front of me,” he said.

“She was definitely underestimated. She’s young, she’s brown and she’s a she,” said Sarah Slamen, a Democratic political consultant, adding that the county’s traditional “king- and queen-makers” are playing a bit of catch-up.

But with all the consternation on one side, and excitement on the other, few have asked a basic question: Who is Lina Hidalgo and what does she plan to do over the next four years?

Hidalgo certainly has an answer.

“I’m one of you,” Hidalgo frequently tells constituents, before launching into her three priorities: public safety, criminal justice reform and making county government more transparent and accessible. “I don’t think county government should be a mystery to anybody,” she says.

She’s laid out a progressive vision for what county government can do for its citizens and has the kind of advocacy background many political leaders lack. Her philosophy for the office is rooted in her immigrant upbringing, one that mirrors the more than 1 million other immigrants who call Harris County home, and if she is successful over the next four years, she could very well be the future of Democrats in Texas.

*

Five hours into Lina Hidalgo’s first commissioners court meeting, Carmen Ivonne, a short, middle-aged woman, stepped up to testify. She began by gently chastising the court — in rudimentary English — for its lack of translators before switching to Spanish and launching into a three-minute comment on minimum wage rates in the county. Sitting beneath an imposing portrait of Sam Houston, Hidalgo — herself fluent in Spanish — briefly summarized Ivonne’s comments for her monolingual colleagues, then stressed the need to address language access in the court.

“I saw it as a moment to recognize the diversity of our county,” Hidalgo later said of Ivonne’s testimony. “I felt a bit disappointed that I hadn’t thought about language access. It sort of underlined the need for community participation.”

The exchange also reminded Hidalgo of her father. When her family first immigrated to Houston, he had a thick Colombian accent and struggled to understand certain English phrases. But over time, he came to see his budding bilingualism as an asset.

“I don’t think county government should be a mystery to anybody.”

Hidalgo speaks in carefully considered sentences with the calm, measured cadence of a seasoned politician. At meetings, she sits between the court’s four other commissioners — all men over the age of 50 — and commands conversations, often about complex public policy issues. Petite, with a bob of curly black hair, she occasionally stumbles over court decorum and lacks the charismatic pizzazz of other newly elected millennial politicos, such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. But she also doesn’t allow her more senior colleagues to speak over her.

“She may not have been born in Texas, but she’s a tough Texas gal,” said Adrian Garcia, the former Harris County sheriff who was elected to the commissioners court in November.

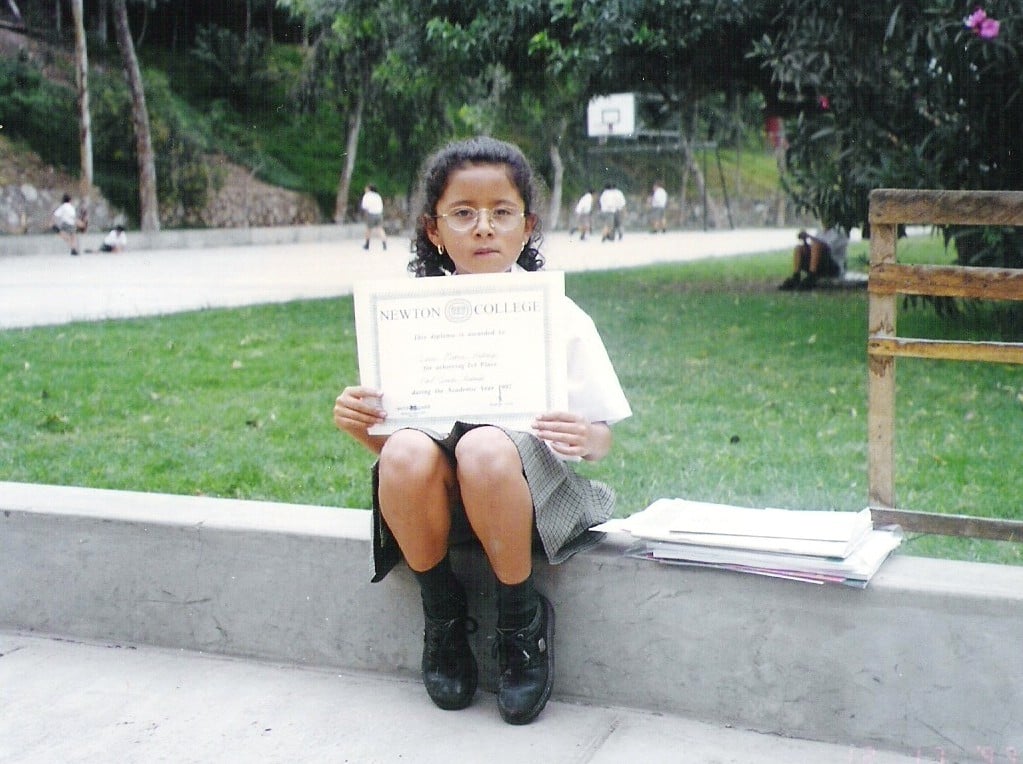

Hidalgo was born into a middle-class family in Bogota, Colombia, at the height of the country’s deadly drug wars. Her family struggled to live normal lives in the midst of car bombs and kidnappings. When Hidalgo was 5, an explosive detonated just blocks from her home, shattering a row of glass windows in the living room as the family played a board game nearby. Her parents decided it was finally time to leave.

For the next decade, the Hidalgos lived in Peru and Mexico City. Her dad worked as an engineer and her mother stayed home with Hidalgo and her younger brother. In 2005, when Hidalgo was 15, her family moved to Houston, where her father got a job at an industrial recycling company. Hidalgo chuckles when she recalls her first impressions of the Bayou City: enormous oil refineries, the sprawling port and the tennis courts at Cypress Falls High School. “My fancy international private school in Mexico didn’t even have such nice facilities,” she remembers.

Hidalgo’s family later moved to a two-story, cookie-cutter home — “very, very suburban,” she said — in Katy, where she graduated from Seven Lakes High School. She spent most weekends at the University of St. Thomas in Montrose, learning everything from how to apply to colleges to how to debate as a member of the National Hispanic Institute, a nonprofit program aimed at training future leaders. In 2009, Hidalgo enrolled at Stanford University, where she studied oppressive regimes and failed states as a political science major. In her spare time, she helped raise funds to establish a public service fellowship for undergraduates.

“From the whole time I’ve know Lina, if there’s been one motivating factor for her, it’s been public service,” said Valentin Bolotnyy, one of Hidalgo’s friends at Stanford. The two connected over their immigrant experience, which Bolotnyy credits as the likely roots of Hidalgo’s commitment to public service. “You have a very salient example of what life could have been, and what life possibly is, for friends and relatives. That all builds up this desire to make the most of the opportunities you have and to appreciate the luck that you have to give back.”

Following graduation in 2013, Hidalgo moved to Bangkok, Thailand, to work with artists, bloggers and journalists as part of Internews, an international NGO dedicated to promoting free expression and press freedom. A year later, she moved back to Houston and began volunteering part-time for the Texas Civil Rights Project. To help pay her bills, she worked as a Spanish-language medical interpreter for patients at the Texas Medical Center.

Her career before politics has been ridiculed in the press as unserious; New York magazine labeled her a “perma-student.” To Hidalgo, however, this time in her life — translating for medical patients on the edge of poverty or working on suicide cases at the county jail — was formative. “When advocates talk about an issue in the community, I know what it is, I’ve seen it. Not all of them, but a lot of them,” she said.

By 2015 Hidalgo found herself somewhat adrift. “We had a number of conversations about the pros and cons of law, or the pros and cons of public policy work, or pros and cons of going to medical school,” Bolotnyy remembers. Ever the ambitious student, Hidalgo enrolled in a joint public policy and law master’s program at Harvard and NYU.

Hidalgo planned on remaining on the periphery of politics, conducting public policy research, perhaps, or working as a civil rights lawyer, but like hundreds of other first-time candidates around the country, that changed with the election of Donald Trump. She halted her graduate studies, moved back to Houston and announced what at the time seemed like a long-shot bid for county judge against a popular, 11-year incumbent 42 years her senior.

*

There’s an oft-repeated adage in county government: If you can count to three, you can get a lot done. The last time Democrats controlled a majority on Harris County’s five-member commissioners court was in 1990, and, as Commissioner Rodney Ellis noted in an interview, this is likely the first time three progressive Democrats — Hidalgo, Ellis and Garcia — have had command of the court. The agenda at Hidalgo’s first meeting reflected this leftward shift: discussions of a $15 minimum wage, approval of a committee to review the county’s sexual harassment training and the backing of a county amicus brief in a lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s inclusion of a citizenship question on the 2020 census.

County governments in Texas, however, are limited in their powers. They can’t pass ordinances, as cities can. They can’t outlaw the use of fireworks or set zoning laws. Against this backdrop, Hidalgo has carved out an ambitious vision for what county government can do on issues ranging from climate change and immigration to indigent health care and ethics reforms. Some say her vision is overly idealistic.

Former Houston Mayor Annise Parker, who met with Hidalgo early in her campaign, said she was skeptical of her understanding of the position’s jurisdictional limits. “When I met with Hidalgo, she had a lot of things that she wanted to work on and most of the issues I agreed with her on, but almost none of them had anything to do with the county,” Parker said, pointing to Hidalgo’s attention to immigration issues. “She’s clearly refined that now and has a better idea of what’s possible, but she was all over the map to begin with.” (Parker briefly considered running for the position herself, but decided against it after concluding that she could do “just as good a job as Ed Emmett but not a better job.”)

“From the whole time I’ve know Lina, if there’s been one motivating factor for her, it’s been public service.”

Hidalgo is undeterred by these critiques. County government is about budgets, she argues — dollars that span dozens of departments and affect every aspect of people’s lives. “I think part of the problem is that there’s been this attitude of, you know, ‘The county doesn’t do that,’” Hidalgo said. “If there’s an issue facing our residents, we’ll go over and around a wall to address it. I won’t say it’s not my problem. I’ll figure out what we can do to help it.” For example, she’s floated the idea of funding an immigrant legal defense fund and cutting off funding to detention centers holding immigrant children.

Three months into her tenure, Hidalgo has already made progress on a campaign promise to make county government more transparent. She’s pledged not to accept political donations from county contractors, a departure from the pay-to-play cronyism that’s subtly plagued the relatively opaque court for decades, according to Jay Aiyer, a former chief of staff to Houston Mayor Lee Brown who now teaches political science at Texas Southern University. She also hired a professional firm to assess talent for senior positions and launched a “Talking Transition” — borrowed from New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio — that includes a survey of Harris County residents and a series of town halls and seminars. County government is relatively arcane, even to Ellis, who despite nearly three decades in the Texas Legislature said he found county government incredibly confusing. “I suspected a lot of times along the way that people were making up rules and traditions on the fly,” he said.

Perhaps the biggest challenge ahead for Hidalgo — and Harris County — is how to protect the region from another devastating storm like Hurricane Harvey. Hidalgo enters office at a particularly ripe moment, just months after voters overwhelmingly agreed to hike property taxes and approve a $2.5 billion flood infrastructure bond, thanks in part to Emmett. (Emmett declined to be interviewed for this story.) Hidalgo campaigned on developing guidelines, which are still in draft form, to equitably distribute funds for flood-relief projects to all communities — not just the wealthy and privileged, as some cost-benefit analyses tend to favor. She also said she’d focus first on tackling “low-hanging fruit,” such as implementing a better flood warning system and improving communication with residents in vulnerable areas.

In contrast with Emmett, Hidalgo has also made a point to address the role of climate change in exacerbating the county’s flood-control issues, drawing praise from environmentalists.

Hidalgo aims to be in the public eye more often than her predecessor, who most residents know as a figure who only appeared during a natural disaster, but she likely won’t become a household name until the next storm hits. She was briefly thrust into the spotlight in mid-March in her role as director of emergency management after a petrochemical storage facility in Deer Park caught fire, releasing a hazardous, black plume of smoke and causing school closures, a shelter-in-place notice and a partial shutdown of the Houston Ship Channel.

Critics pounced on Hidalgo’s performance briefing the public, with some yearning for the leadership of her predecessor — “Bring back Judge Emmett,” one user wrote on Twitter — and others noting the “ums” and “likes” in her speech patterns. The Harris County Republican Party called Hidalgo’s “incomprehension” about certain air quality data “alarming.” But others noted, yet again, a whiff of condescension. Writing in the Houston Chronicle, John Nova Lomax said the criticism was “completely unfair and counterproductive,” and that the subtext was people wishing for a “silver-haired white man up there rather than a young Hispanic woman.”