Robert Zarestsky Reminds Us Why Albert Camus is Still Worth Reading

A version of this story ran in the December 2013 issue.

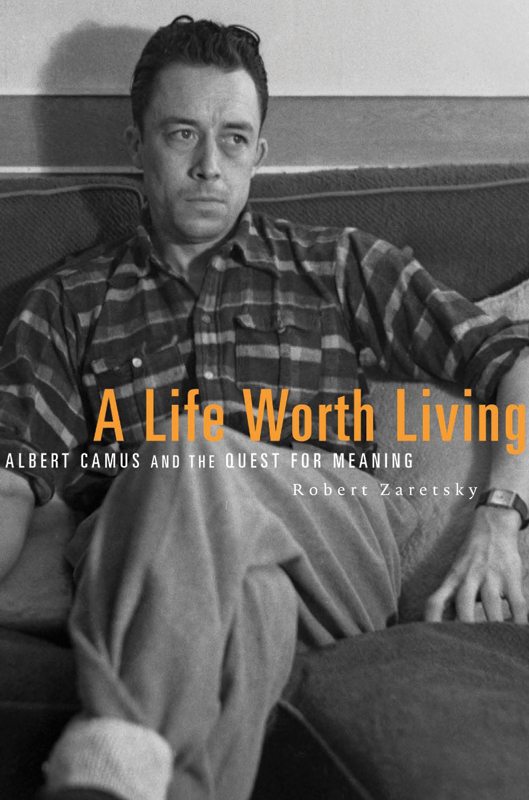

Above: A Life Worth Living: Albert Camus and the Quest for Meaning

By Robert Zaretsky

Harvard University Press

230 pages

$22.95

Though only 46 when he died in an automobile accident in 1960, Albert Camus lived long enough to experience the extremes of both reverence and revulsion. Publication of his astounding first novel, The Stranger, in France in 1942 transformed Camus into a literary rock star, a war-weary generation’s fulfillment of Hemingway’s demand for “a built-in, shockproof, shit detector.” Camus burnished his reputation with The Myth of Sisyphus (1942) and The Plague (1947), becoming, with Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, a leader of the hottest movement in European thought: Existentialism. However, Camus’ refusal to embrace the glib politics of his contemporaries and a nasty spat with Sartre led to ostracism by cultural trendsetters. By 1957, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, five months after publishing The Fall, his acid portrait of a cynic, Camus suffered depression over his rejection by the intellectual elite of France, a country in which he, a native of Algeria, was an outsider. He remains an outsider: A recent effort to move his remains to lie beside Voltaire, Rousseau and Hugo in Paris’ Pantheon failed.

In the United States, though, Camus has always been adored. Inverting the Jerry Lewis syndrome, Americans have taken to Camus while Balzac and Stendhal remain esoteric imports. Books about Camus are most often written in English (disclosure: I have published three). Robert Zaretsky’s second book on Camus arrived in time for the centenary of the novelist’s birth, on Nov. 7. In his first, Albert Camus: Elements of a Life (2010), Zaretsky, a professor of French history at the University of Houston, devotes chapters to key moments in the author’s career. In his cogent new book, A Life Worth Living: Albert Camus and the Quest for Meaning, Zaretsky proceeds topically, with chapters on absurdity, silence, measure, fidelity and revolt. For each, he situates Camus’ thoughts within their historical context. The dire plight of the conquered Berbers, which Camus reported on, and the extermination of France’s Jews, which he resisted, concentrated his mind on the absurdity of the human condition and the social order. Camus’ own predicament as an Algerian of European descent sympathetic to both sides of the Algerian War led him to recognize a collision of incommensurable truths and embrace classical moderation. Visceral revulsion at torture and execution made him reject abstractions that rationalize injustice and instead struggle for what he called “a world in which murder is not legitimized.”

Zaretsky identifies Camus as a moralist, not a moralizer, one who poses questions rather than imposes answers. Like such courageous moralists as Montaigne, Voltaire, Hugo and Zola, Camus extended his private quest for truth into the public sphere. Zaretsky highlights “Camus’s lucidity in recognizing our absurd condition, his inattentiveness to the silences of the world and its denizens, his fidelity to our common condition, his insistence on measure when we rebel against those who deny our shared humanity.” In pithy prose worthy of his subject, Zaretsky reminds us that, in an age of suicide bombings and state-sanctioned murder, Camus is an author worth reading.