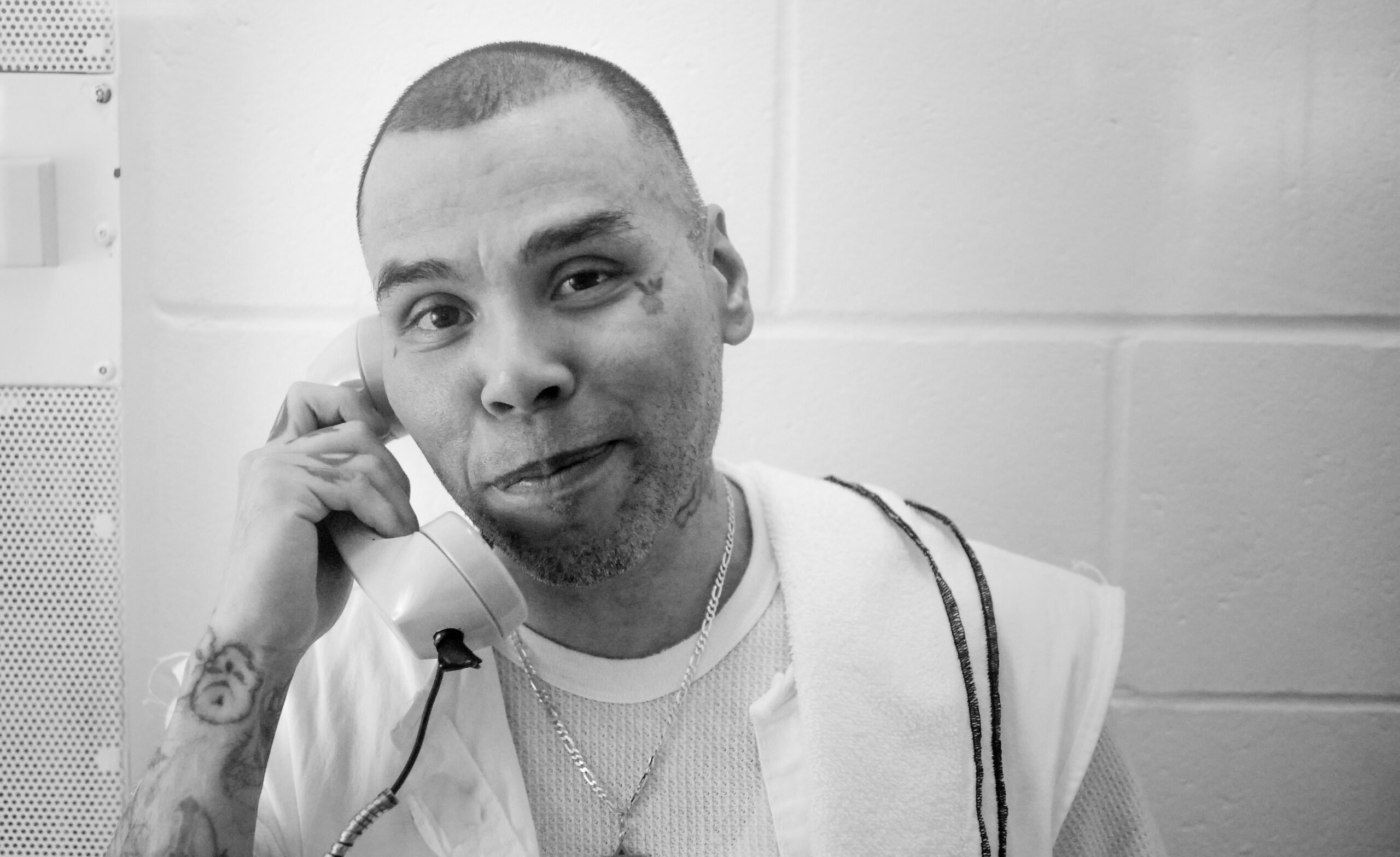

Finding God, Asking State to Find Mercy on Death Row

Ramiro Gonzales will be put to death next Wednesday, unless the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles recommends clemency.

Update: The State of Texas executed Ramiro Gonzales by lethal injection on June 26.

The State of Texas plans to execute 41-year-old Ramiro Gonzales next Wednesday, June 26. Not for the first time, his lawyers are pleading with Governor Greg Abbott and the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles for clemency. This time, attorneys are arguing that his religious growth and ministry on death row means he deserves to live.

Gonzales was sentenced to death in 2006 for the murder of Bridget Townsend, who witnessed Gonzales robbing his drug dealer’s home, in 2001.

His attorneys filed an application for clemency on June 5 and requested a hearing on Gonzales’ upcoming execution. The board denied the hearing request but will vote on whether to recommend the governor grant clemency by Monday, two days before his scheduled execution.

“The role of executive clemency is, supposedly, to prevent miscarriages of justice that might yet occur due to the fallibility of our criminal legal system,” said Thea Posel, one of Gonzales’ attorneys. “On a basic level, it is an opportunity for those in power to grant mercy and to recognize not only grave injustices but also the power of rehabilitation and the human capacity for change.”

Texas governors have very rarely granted clemency to prisoners on death row. The only time Governor Greg Abbott has done so was in 2018, when Abbott commuted Thomas Whitaker’s sentence after his father—and would-be victim of Whitaker’s 2003 familicide plot—pled for mercy for his son.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) stayed Gonzales’ original execution in July 2022 two days before the date, after an expert who had testified that Gonzales posed a future danger to society walked back his testimony. The state’s highest criminal appeals court ordered a lower court to review the case given that new information. At a lower court judge’s recommendation early this year, the CCA dismissed Gonzales’ claim, and the state set his June 26 execution date. The U.S. Supreme Court also declined to hear the case in February.

While in prison, Gonzales became one of the first members of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice Faith Based Program on Death Row, where participants live in a special housing area and take religious classes. State prison systems have provided similar programs to the prison population for decades, but TDCJ became the first to extend the initiative to death row in 2021. According to his clemency application, Gonzales found God in the Medina County Jail ahead of the trial for Townsend’s murder, after a visiting preacher gave him a Bible.

Gonzales’ participation in the death row program and his spiritual journey are at the heart of the calls for clemency, both from his lawyers and tens of thousands of people who have signed online petitions against the scheduled execution. Before he received his execution date and was moved to a special “death watch” area, Gonzales was a peer mentor and coordinator for the Faith Based Program and often ministered to other people on death row. He received the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree from a theological seminary while in prison.

“Is clemency called for in a case where executing [Gonzales] is the judicially imposed sanction for a heinous crime, but granting him mercy would save souls that would otherwise be lost?” his clemency application states.

Such religious language is common in appeals for clemency in Texas. Condemned Texans often ask for clemency on religious grounds, pulling from scripture and theology to draw parallels between flawed religious figures and those on Texas’ death row, and proclaiming the transformative power of faith. Historically, these arguments haven’t swayed governors and their pardon board appointees to show mercy, even in Texas.

Last October, Will Speer, the first inmate coordinator for the Death Row Faith Based Program, was set to be executed, and despite his extensive work with the program and his spiritual growth, the board unanimously denied his clemency application, which highlighted his religious devotion. For reasons unrelated to his clemency application, the Court of Criminal Appeals granted a stay five hours before he was supposed to be killed.

Speer told the Observer this week that it’s difficult for men in the program—which he said consists of “not just some fluff that sounds good [but] life changing, life growing, life giving classes”—when one of their leaders gets an execution date.

“There are men who are new to the change, some new to faith,” he wrote in a message to the Observer. “They need lots of help to see things in a new light, or a different perspective. It’s not always easy to shake off 20, 30, 40, years of living with one mentality.”

An op-ed in The New York Times lauded Gonzales’ efforts to donate and his spiritual growth on death row. “His attempt to donate a kidney represents something beyond a modification of the simple logic of an eye for an eye,” wrote Rachael Bedard, who worked as a palliative care physician at Rikers Island for five years and met with Gonzales after hearing about his case. “It is an expression of hard-won self-knowledge and the good he has found in himself, commingled with remorse.”

In addition to highlighting his religious turn, Gonzales’ current clemency application includes grim details about his childhood—mitigating circumstances like childhood abuse and mental illness are also common threads in many clemency applications in Texas.

Raised by his mother’s parents, he was allegedly sexually abused by his cousin and others when he was a child, according to court documents. He became addicted to drugs after his aunt, with whom he shared a close bond, died in a car accident when he was 15. He struggled in school, repeating multiple grades—by the time he dropped out at age 16, he was still in the 8th grade.

But Gonzales’ attorneys told the Observer that in this second clemency application, they wanted to focus not just on the reasons Gonzales “does not deserve to die,” but to highlight the reasons he should live and continue his ministry on death row.

“In the free world, ministers and faith leaders are viewed as pillars of the community. … In the same way, Ramiro is a leader in prison society,” Posel said. “He is deserving of mercy for numerous reasons, but faith is inextricably intertwined with all of them, as it is an essential part of who he is and how he has attempted to atone for his sins and the pain he has caused.”