More Highways, More Problems

Highway expansion is the Lone Star State’s status-quo solution to easing traffic—but it actually leads to more congestion and displaced communities.

Bruce Elementary School sits in the shadow of one of Houston’s countless towering, concrete overpasses. From the playground, the sound of cars zooming past and heavy-duty trucks heading to Interstate 45 drowns out the voices of community advocates. Dozens of people have gathered outside the school’s front gates for a press conference, ahead of a late July vote by the Houston-Galveston Area Transportation Policy Council that allocated $100 million toward expanding the portion of the highway closest to the school.

The noise pollution here is obvious, but less so is the fact that the asthma rate at Bruce Elementary—where 99 percent of students are black or Latinx and qualify for free or reduced lunches—is more than double that of Houston Independent School District’s overall rate. Students are exposed to higher rates of air pollution from the thousands of vehicles that speed past the school’s playground every day, according to a report from Air Alliance Houston, one of several advocacy groups trying to stop the expansion.

But a few days after the press conference, the Houston-Galveston Area Council approved the project’s funding. It’s a small sliver of the $7 billion needed to implement the North Houston Highway Improvement Project. The massive expansion will eventually add 24 miles of freeway along I-45 as well as I-10 and 610, which forms a loop around downtown. It’s all in the hopes of easing congestion and improving commute times as the country’s fourth-largest city continues to grow.

As in most of Texas’ sprawling cities, it seems like Houston’s only solution to reduce traffic and speed up commutes is to tack on more lanes to existing highways. The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) estimates that over the next decade, almost $20 billion will be spent on highway improvement projects along the state’s most congested roads. Today, there are at least three multimillion-dollar highway projects underway across Texas—I-45 in Houston, the I-345 bridge in Dallas, and I-35 in Austin.

No matter how fast the state builds highways, they keep filling up. An expansion of Interstate-10, also known locally as the Katy Freeway because it connects the suburb to downtown Houston, was completed in 2011 with a $2.8 billion price tag. Its 23 lanes were supposed to save commuters from being stuck in gridlock during rush hour. By 2014, commutes were even worse than before the expansion. The phenomenon is called induced demand. The new, open stretches of freeway incentivized more drivers to get on the road than ever before. Year after year, commuters always seem to be stuck in traffic. And as massive concrete overpasses rise and fill up, suburban drivers aren’t the only ones suffering the consequences.

*

Plans call for I-45 to encroach on the property line of Bruce Elementary. More cars will bring more air pollution. Yet when the construction is complete, there may be fewer children left to breathe the fumes; more than 100 residences will be lost, displacing some of the families who send their children to Bruce Elementary. As of now, neither TxDOT nor the city has plans to provide new housing to those families; they offer only a stipend.

That the I-45 expansion is disproportionately affecting neighborhoods of color isn’t an accident: It’s a product of history. In a working paper for the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, economists Jeffrey Lin and Jeffrey Brinkman detail the history of “freeway revolts”—public protests against the construction of highways through the middle of dense, urban communities. The most successful revolts were typically led by highly educated, affluent, white residents in the 1960s.

“Families are being priced out, bought out, hustled out.”

Federally managed highway systems were often built with the blatant ulterior motive of “slum clearance,” aimed at removing mostly middle-class black homes and businesses from city centers. In other cities, including Austin, highways became the physical manifestation of previously unmarked, de facto lines of segregation.

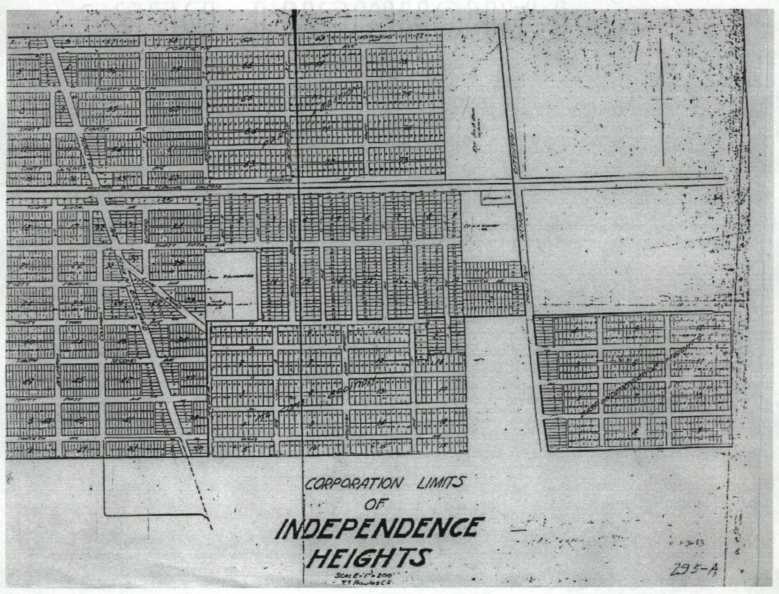

Houston has an especially long history of highway construction scarring communities of color. In 1915, when the community of Independence Heights, seven miles north of downtown Houston, obtained a city charter, it became the first incorporated black city in Texas. Independence Heights had its own newspaper, schools, and churches. Tanya Debose’s great-grandfather owned a house there in 1924. That home was a powerful symbolic victory for her ancestors, Debose, the executive director of the Independence Heights Redevelopment Council, tells the Observer—a piece of the American Dream, a parcel of land owned by the descendants of slaves.

But by 1959, well after Independence Heights was annexed to the city of Houston, that dream was demolished to make room for Interstate 610, which forms a ring around Houston’s inner core. “There goes my family’s home on Loop 610,” Debose says. “And here we are again, faced with the same scenario.”

The new I-45 expansion will tighten the belt of freeways around what remains of the historic neighborhood, displacing a storied black church and dozens of residential homes—and that’s on top of the buyouts that have already occurred here for flood mitigation. Independence Heights is shrinking. Debose is attempting to fight off some of the damage by getting the neighborhood’s sites placed on the National Register of Historic Places, which would protect some of the buildings from displacement and destruction.

“Families are being priced out, bought out, hustled out. Eventually, there will be no Independence Heights,” she says. “They kind of snuff you out. I don’t have a better word for it.”

In Dallas, that’s more or less been the fate of the freedmen’s town known as Deep Ellum, which is adjacent to I-345, a mile and a half of elevated freeway on the edge of downtown Dallas. In the 1880s, the Central Track Railroad separated the black neighborhood from the rest of downtown. It was heavily industrial, yet black businesses also thrived here, and Deep Ellum eventually became a cultural center where jazz and blues flourished.

In 1969, the highway was built along the path of the long-gone railroad line, pushing out residents and destroying the neighborhood’s urban fabric. With the onset of white flight and disinvestment in central cities in favor of the suburbs, Deep Ellum was already sliding into economic decline by the time the highway was added to the landscape.

Today, I-345 is in need of repairs totaling $11 million. But urbanists instead imagine razing the overpass altogether, and replacing it with a walkable, mixed-use development, reconnecting Deep Ellum and Downtown after more than a century.

The plan has received a positive, if lukewarm, reception from local leaders and even TxDOT. Deep Ellum is now a trendy neighborhood that sits on the threshold of reinvention. The civic activists who want to see the highway torn down are mostly white and largely represent the city’s business interests. New yoga studios and Uber’s decision—swayed by a city tax incentive—to open a new office in Deep Ellum are seen as the benchmarks of successful revitalization here. But the descendants of the original freedman’s town are largely absent from conversations about the neighborhood’s redevelopment and the fate of the highway. They were displaced further west and south, according to the city archivist. Those patterns of racial segregation persist in Dallas to this day. Save for a few historical buildings, there isn’t much left to mark the community that shaped Deep Ellum a century before the government rammed the highway through it.

*

“A lot of people aren’t really interested in thinking 25 years into the future about transportation policy,” says Tina Geiselbrecht, a research scientist at Texas A&M’s Transportation Institute. Before a highway is ever built, it requires decades of planning and coordination between federal, state, regional, and city agencies. Those plans take into account expected population and economic growth to understand where the jobs are and which direction commuters will go—as well as federally required environmental impact reviews.

That means in order to have a say, residents need to attend local transportation meetings more than a decade before the concrete starts to pour—a tall order, Geiselbrecht says. “[People get] really interested when construction is imminent and they can see how it’ll impact them,” she says. “They also get interested when congestion gets really bad and they are spending an hour on a 15 mile commute.”

It’s much easier to add to an existing freeway than to reimagine the mobility of an entire metropolitan area.

“Infrastructure projects are disruptive by their very nature,” says Kyle Shelton, a director at Rice University’s Kinder Institute, and the author of a book on Houston’s highway development and civic engagement. He also points out that it’s much easier to add to an existing freeway than to reimagine the mobility of an entire metro area. That’s how highways (and their expansion) become received wisdom, passed down from one generation of urban planners to the next. And it’s why the fundamental function of a highway hasn’t changed much since the system was first imagined in the mid-20th century: shuttling newly minted suburbanites back and forth from the city center. “The logic of highway development is still underwriting that arrangement,” Shelton says.

Most of the funding at the federal level is already earmarked for highways, while public transit projects are typically funded at the city level, where revenue streams are much smaller. Dallas’ transit system, for example, is funded in part through a one-cent sales tax. The statewide gas tax, which funds highway projects, is about 38 cents per gallon.

Suburban voters are sometimes reluctant to embrace mass transit projects that may bring denser development. In Plano, a failed mayoral candidate who ran on a platform of “Keeping Plano Suburban” by opposing both expansion of public transit and higher-density housing won a seat on the city council this year.

That turns the entrenched logic of transportation into a self-fulfilling prophecy: More people in Texas’ suburbs means more cars on the road toward downtown jobs, requiring more freeway lanes that eventually become gridlocked. But Texans increasingly want more access to public transit and alternatives to highways. A 2016 poll from Texas A&M’s Transportation Institute asked Texans to name the biggest transportation issue affecting their daily lives; public transit was the fourth most commonly cited. Respondents also pointed to improving services over increasing road capacity as the best solution.

At least there’s a growing recognition—among rural residents who have no choice but to rely on cars, suburban commuters perpetually caught in rush-hour gridlock, and urban communities breathing the fumes—that the system as it was built is in dire need of repair.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Texas Workers Are Dying on the Job at Alarming Rates: “Literally, we’re not holding employers liable for the lives of their workers.”

-

Climate Change Will Drive Up Energy Use in Texas and Beyond: A new study found that global energy demand could rise by as much as 58 percent in the next 30 years due to climate change. But Texas’ electric grid doesn’t exactly account for this climate impact.

-

Dammed to Fail: An Observer investigation finds that unregulated dams across Texas are increasingly failing — putting people and property in jeopardy.