Letters from Death Row: Alone on the Inside

In an informal Observer survey, death row inmates describe a world of extreme isolation, where mental illness is both cause and symptom.

Above: Daniel Lopez, 23, waits in Polunsky Unit's visiting room for guards to escort him back to his cell on death row.

The second in a series…

In the spring of 2014 I sent identical letters to the 292 inmates on Texas’ death row. The letter consisted of 10 questions designed to find out more about life for the condemned. I inquired, for example about: the effect that solitary confinement has on them; whether they had found religion in prison; what sort of childhoods they had; and what books they read.

The aim was twofold: to shine a light on little-known areas of life on one of the most notorious death row wings in the United States, and to see if patterns emerged. Was there a trend in death row inmates who had abusive childhoods? Was there a genre of fiction that those in solitary confinement preferred?

I addressed the questionnaires to the Polunsky Unit in Livingston, where men who are on death row are housed. I did not send the same questionnaire to the seven women on death row housed at the Gatesville Unit near Waco. That’s because women on death row in Texas are held under different conditions. They can participate in work programs. Some can watch TV outside their cells. They can occasionally associate with other death row inmates. And they are allowed to knit and sew. I intend to approach the women on Texas death row separately for an extension of this project.

Forty-one inmates responded by filling out the questionnaire, writing a letter expanding on their answers to the questions or both.

Twelve letters were “returned to sender,” unopened for various reasons. A sticker that read “Refused. Unable to forward” was attached to five of them. Three inmates had been moved off death row and TDCJ hadn’t updated its public database Four letters were returned marked “unable to forward.”

Just under 14 percent of the inmates responded. Perhaps something can be gleaned from looking at the non-responders, too.

Some inmates prefaced their answers by saying they were suspicious of the media and indicated that they believed not many would respond. Just as some inmates have refused to take the hour per day of recreation offered to them—perhaps indicating they had given up on living, preferring to stay in their cells 24/7—others wrote that they’d lost hope that communicating with the outside world could improve conditions for them.

The survey doesn’t purport to be scientific, but the results are revealing and fascinating. Over the next couple of months the Observer will publish a series of stories based on the responses to the questionnaire, expanding on them with the voices of the death row inmates who replied, and giving context where appropriate through analysis by experts.

***

Coy “Elvis Wayne” Wesbrook was 40 when he arrived on death row in September 1998. For the last 17 years, the Polunsky Unit, a concrete fortress set amid farmland and pine woods in the East Texas town of Livingston, has been his home. For the past five nobody has visited him, he says. According to prison rules, Wesbrook, who was sentenced to die for killing his estranged wife and four other people at a party after finding her in bed with two of the men, can leave his cell one hour a day for recreation. But a severe case of depression keeps Wesbrook from wanting to set foot outside his cell. Aside from the occasional shower, for which he’s extracted by two guards, the 57-year-old is cell-bound 24/7. He’s overdosed 12 times.

Depression and other forms of mental illness are not unusual for inmates on death row. In Texas, a quarter of inmates facing execution, and therefore held in solitary confinement, have been diagnosed with either a serious mental illness or intellectual disability. But the Observer found that prisoners often choose a life of permanent isolation, refusing to leave their cages. It’s a catch-22: Mental illness can lead inmates to never leave their cells, never leaving their cells can exacerbate—or even cause—mental illness.

According to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, death row inmates are offered an hour of recreation each day, alone, in a separate area of the prison. But many refuse and are instead confined to the same 12-by-6 feet cell for decades. Others are abandoned by family and friends—either because they no longer stand by them or because they simply cannot afford to make the sometimes hundreds of miles visit to the prison. What effect does this have on their psyche? Do harsh conditions induce depression, or other mental disorders? I drew up a list of 10 questions to find out more about how death row inmates in Texas spent their time—including how often they were visited, and whether they took recreation when it was offered—and vetted them with a trauma psychiatrist.

Of the 41 inmates who responded to the questionnaire, eight (almost 20 percent) said they never take recreation when it’s offered and 27 percent take it less than three times a week. In addition, 17 percent of respondents admitted to self-mutilation.

Inmate Troy Clark said he slashed his wrists the very first day he was taken down to the cells after being sentenced to death in 2000 for killing his former roommate.

Jeff Wood, who faces execution for his part in the 1996 murder of a service station employee in the course of a robbery, wrote that in the past he has broken the knuckles in both his hands from punching the concrete walls of his cell. “Blood was everywhere,” he recalled in his letter. “I also had my stomach pumped and an IV [inserted] from ODing on about 200 different pills.”

There’s no way to independently verify claims like these. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice considers self-harm part of a prisoner’s medical history and will not comment publicly. What is certain is that at least 13 prisoners have committed suicide on death row in Texas since executions resumed in the state in the 1970s following a brief moratorium. How many more have attempted suicide is unknown.

According to Anthony Graves, who spent 18 years on death row for a crime he didn’t commit, administrative segregation has a debilitating effect on human beings.

“It breaks a man down,” he said. “I witnessed people yelling out in the middle of the night—people who had been there no more than six months. Men overdosing on medication, trying to kill themselves. Others cutting their throats.”

Tony Medina used to take recreation any time it was offered. Convicted of the drive-by shooting of two people in Houston in the mid-’90s, he wrote that for the past few years he’s taken his hour a lot less. “I used to go any time I had the chance, rain, cold—no matter. I just wanted to get out of this cage. Now, sometimes I will refuse for a month straight, take recreation once, then refuse again for another month. I recognize it is a form of depression, keeping myself hidden away, but these walls just have their hold on each man in their own way.”

I asked Medina if he’d ever harmed himself.

“No,” Medina wrote. “But it does not mean I have not been on the edge. … Being caged up like animals, your mind can do funny things. Combine this with friends and family falling away from you faster than a concrete block falling off a building, and sometimes you have to fight to find a reason to stay alive. I know I do. I have seen the suffering my mom goes through as she tries to make sure I have visits so I can leave my cage. I see the hardships she has to go through, and I just feel like sometimes if I ended it here, then she could get on with healing.”

The exercise yard for death row inmates at Polunsky is not much of a yard at all. Surrounded on all sides by concrete walls, the only view of the sky in the yard is through a grill in the roof. For security reasons each inmate has to take recreation separately, in isolation. A corrections officer formerly assigned to the death row wing at Polunsky once told me that each time an inmate leaves his cell, two guards strip-search the inmate—an exhausting practice for the guards and a dehumanizing one for the inmates. “It can wear you down,” the former guard told me.

Inmate Thomas Whitaker said the longer someone is incarcerated, the less likely he is to take recreation when it’s offered. “It’s stultifiyingly boring indoors; you cannot escape the inane conversation,” he wrote.

Whitaker, who was convicted of ordering a hit on his family in 2003 in order to pickup an inheritance, wrote that instead of taking recreation he focuses on painting, studying and writing essays and letters to friends. “None of this can be done in the [recreation] rooms. Sometimes they [the guards] leave you in those cages for ridiculous periods of time, meaning that you can lose half a day because some guard is too lazy to do his job.”

Whitaker also claimed that long periods of solitary confinement can result in loss of speech. “When you live in an environment where nearly everyone is hostile to you, you learn to say less and less until you arrive at the point where vocalization seems increasingly odd to you,” he wrote. “Words to a prisoner are almost always meaningless, because 99 percent of the ones spoken to you are lies.”

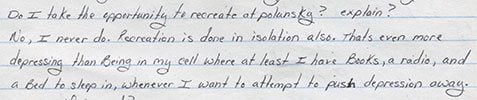

Fellow inmate Cortne Robinson agrees. He never takes recreation because, he wrote, “that’s even more depressing than being in my cell where at least I have books, a radio and a bed to sleep in.” Perhaps ironically, Robinson claimed that spending time in his cell where he has things to occupy his mind actually helps combat his depression. For others, it’s the reverse—that hour outside gives them the chance to see something different, even if it’s a cell by another name. Others use it to interact with the guards—indulging that craving for human contact, even if it’s with their jailers.

Loss of contact with family and friends—either because they no longer stand by them because of their conviction or because the journey to visit them on death row is just too long and costly—is another source of depression and loneliness. Inmate Arthur Williams wrote that because he is from Minnesota, it’s been hard for friends or family to visit him in Texas. During his 30 years on death row, many of them have died. “My family now consists of two older sisters (along with various nieces and nephews) that live in Minnesota. It’s been a couple of years since either of them visited because of health problems or other priorities.”

But Williams made clear that his lack of visits doesn’t mean a lack of love or concern. His attorney fees are not cheap, he wrote, and his remaining family members have been helping cover the costs instead of using the money to come down to visit him. “I’m doing far better than a number of guys here,” he said.

Juan Ramirez wrote that his last visit from a family member was three-and-a-half years ago. He has been on death row since December 2004. Hector Medina, meanwhile, claimed that as of last spring, when the questionnaire was sent, he hadn’t had one visitor since he arrived on death row in March 2009.

According to a 2006 U.S. Department of Justice report on the mental health of inmates, more than half of those incarcerated in American prisons and jails had a mental health problem. Trauma psychiatrist Frank Ochberg, who was involved in the early pioneering research into post-traumatic stress disorder, told the Observer that death row inmates find themselves in a vicious circle of depression that causes self-isolation, which in turn contributes to depression.

“Depression is a state of lethargy, with feelings of hopelessness, helplessness and worthlessness [and) some advocates of harsh incarceration would argue that prisoners should feel this way,” he said, “but we doctors see depression as a treatable medical illness and want poor health to be ameliorated, no matter who carries the burden of illness.”

Ochberg said he doubts that prison staff would try to motivate a depressed inmate to exercise, seek visitation, or liven up in general.

“A non-depressed inmate may avoid exercise and interaction for different reasons,” he told me.

“Like fear of attack, psychotic delusions, anger, physical illness.” Others, meanwhile, may have strong feelings of guilt and remorse leading to a rational decision to eliminate sources of pleasure such as an hour’s exercise in yet another windowless cell.

Then there is Albert Love, sentenced to die for a gang-related murder. His vision of the future could help with the monotony, isolation and fear of life on death row–or perhaps it could be construed as delusional. Love wrote that he has never self-harmed, takes recreation every time it’s offered and believes he will one day be released. “I believe in the promises of Psalm 107: 14-16 and Psalm 118: 17-18,” he wrote. “I trust God that the chains are already broken. I’m just waiting for it to come to pass.”