Ken Paxton’s ‘Shoddy’ Prosecution of a Midwife Is Part of a Strategy to Expand His Power. Low-Income Houstonians Are Paying the Price.

Maria Margarita Rojas is the first healthcare provider charged for abortion care under Texas’ strict criminal ban. Her attorneys say the state has no evidence—yet her clinics remain shuttered.

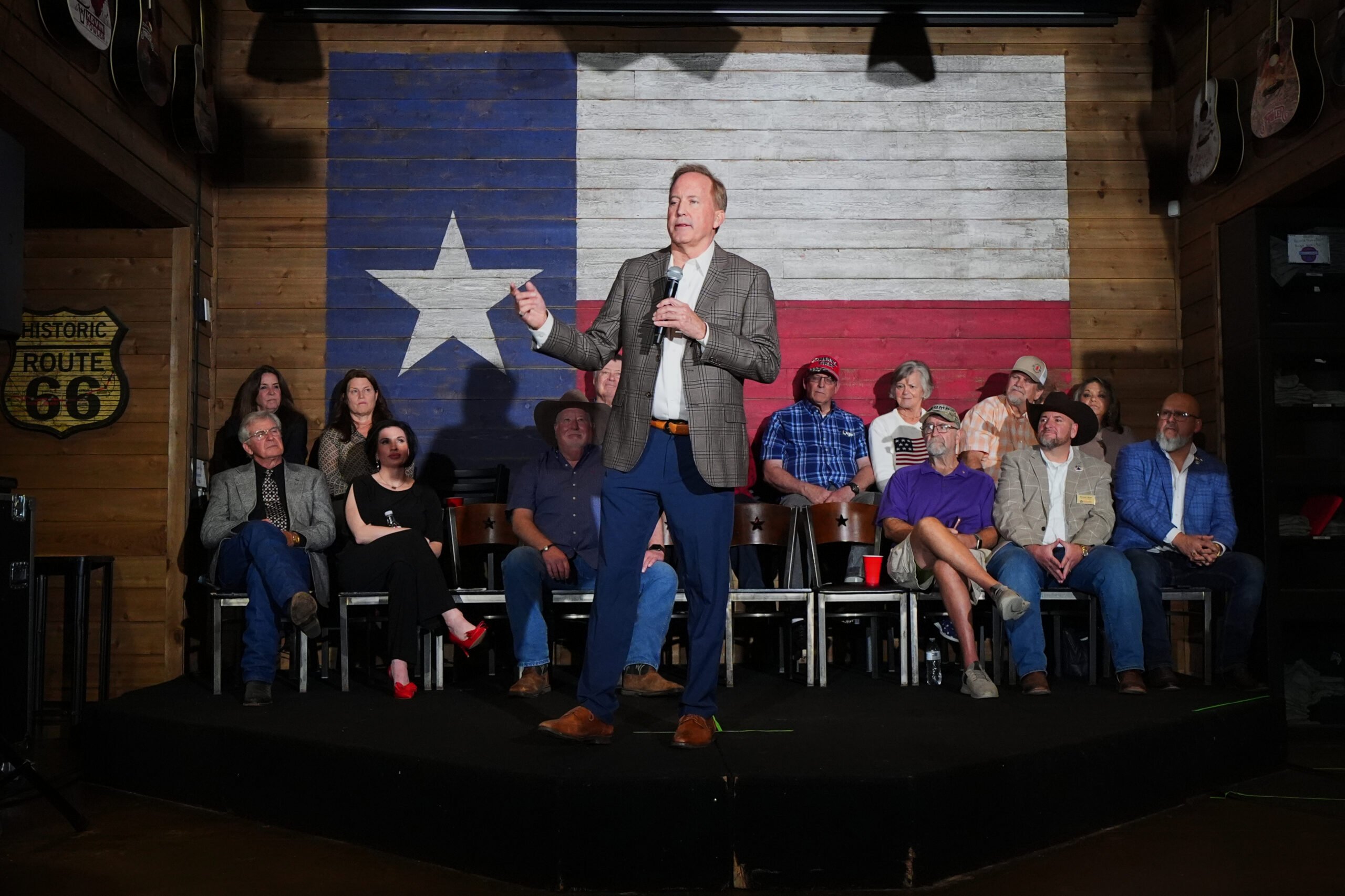

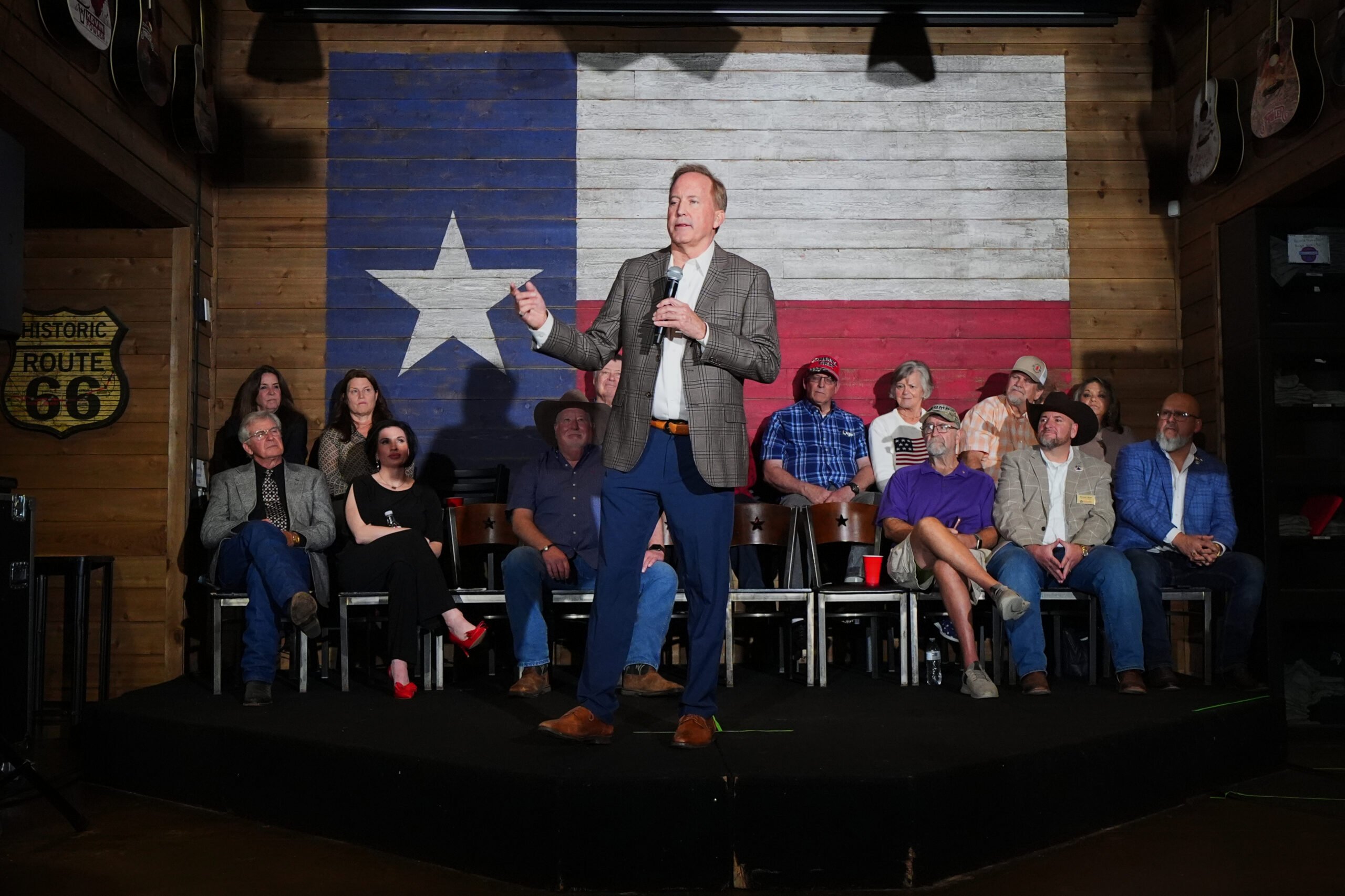

Houston attorney Nicole DeBorde Hochglaube sat flabbergasted at her desk in early October. A press release from Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton had just touted the arrest of eight people affiliated with a network of Houston-area medical clinics alleged to have practiced abortion care in violation of the state’s extreme ban. Paxton, currently a U.S. Senate candidate as well, labeled the individuals a so-called “cabal of abortion-loving radicals” and denounced their actions as “evil,” amid an ongoing case. The sensational release served as an update to his office’s earlier announcement of the arrest of the clinics’ founder, 49-year-old midwife Maria Margarita Rojas, last March.

“A prosecutor who is truly interested in justice does not blast out a public press release like this to the media while a trial is pending. Nothing has been proven in court yet, and this inflammatory language is just meant to fan the flames of public outcry and poison a jury pool before the facts are heard,” Hochglaube, who serves as Rojas’ criminal defense lawyer, told the Texas Observer. “It’s unethical and irresponsible.”

Rojas is believed to be the first healthcare provider criminally charged for abortion care after the fall of Roe v. Wade in 2022, and she is certainly the first in Texas. The unprecedented prosecution marks a sharp escalation of Paxton’s zealous ongoing attacks on reproductive health providers—and signals his desire to expand his powers to go after those he believes are in violation of abortion law. Paxton’s office is prosecuting the criminal cases, after the Waller County district attorney referred them over, and his office also initiated a separate civil case to shut the clinics down; a status hearing in Rojas’ criminal case is scheduled for early June, while oral arguments in the civil case, which is on appeal, are set for Thursday in Houston.

Hochglaube said Paxton’s “desperate” attempt to smear charged individuals is indicative of the state’s overwhelmingly flimsy argument against the medical workers.

On March 17, Paxton announced the arrest of Rojas for purportedly providing an illegal abortion as well as practicing medicine without a license at her network of low-cost clinics in the Waller, Cypress, Katy, and Spring areas of the Houston metro. The next day, he announced the arrest of one of her employees, Jose Ley, on the same charges—specifically noting Ley’s status as a Cuban immigrant paroled in under Joe Biden’s “open borders policies.” To date, a total of nine arrests have been made in the case. Texas enforces one of the strictest criminal abortion bans in the United States, with no exception for rape, incest, or severe fetal abnormality. Only recently did lawmakers provide clarity about when doctors can perform emergency abortion care, and even that measure hasn’t satisfied reproductive health advocates. If found in violation of the law, Rojas could face up to life in prison, while practicing medicine without a license carries a penalty of up to 10 years in prison.

“Texas law protecting life is clear, and we will hold those who violate it accountable,” Paxton said in announcing Rojas’ arrest.

However, Rojas’ attorneys say the accusations against her are baseless. In a case conducted with “complete shoddiness,” the state has offered paltry evidence to show that Rojas or her colleagues participated in abortion care at all, said Marc Hearron, interim associate director of litigation with the Center for Reproductive Rights, who serves as Rojas’ attorney in the civil case, which has resulted in an injunction that’s shuttered Rojas’ clinics for nearly a year now.

“There’s an almost shocking lack of evidence around these abortion care accusations,” said Hearron. “What you’re seeing is an attorney general grasping at straws and rushing to indict anyone during an election year.”

A native of Peru, where she practiced OB-GYN care, and a certified midwife in Texas since 2018, Rojas has overseen more than 700 births in hospital and community-based settings, including at one of her clinics, the Houston Birth House. In January 2025, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission received an anonymous complaint claiming two abortions were performed at another of Rojas’ clinics, Clinica Waller LatinoAmerica. This spurred the Medicaid Fraud Division within the attorney general’s office to investigate. Investigators surveilled Rojas’ clinics for months and say they identified a patient (named as “E.G.” in court documents) who claimed to have been given abortion pills under Rojas’ care after being told her pregnancy had a low chance of viability. Investigators also say they found a medicine bottle containing misoprostol, a drug that can induce abortion.

In an 84-page appeal—part of the civil case, which state attorneys have successfully transferred into an appeals court custom-made by the GOP Legislature in 2023 for litigation involving the state—Rojas’ attorneys criticize investigators for their lack of medical expertise and point out their surveillance was limited to outside the clinic: “Investigators never observed any medical practice by anyone inside the clinics,” they write. Moreover, without any tangible proof, E.G.’s statements to the investigator amount to hearsay, a conclusion Republican Waller County District Judge Gary Chaney—who issued the injunction in the civil case and is also presiding over the criminal case—has appeared to agree with so far. As for the misoprostol, the low dose found (one-fourth of what would typically be given) is “inconsistent” with abortion care. The drug can be prescribed to patients for a range of medical purposes including treatment of ulcers, miscarriage management, or to prevent hemorrhaging. Investigators also didn’t find mifepristone, which is given in combination with misoprostol as part of a two-drug abortion medication regimen.

“[State investigators] did not report finding mifepristone, the tools that would be used in a surgical abortion, or patient records indicating that any patient had received an abortion,” the attorneys write. “They did not find any documents anywhere indicating that abortions were being offered at the clinics.”

While the state is trying to criminally charge Rojas with practicing medicine without a license, lawyers point out she never claimed to be a physician, but rather a midwife, someone who offers holistic reproductive healthcare during pregnancy, labor, delivery, and postpartum. She was licensed as a midwife, and midwives like her are allowed to provide prescription drugs under a licensed physician, as she did.

“None of the state’s arguments add up, yet Paxton has labeled Rojas and her colleagues ‘abortion-loving radicals’ and said ‘Let’s just throw them all in jail’,” said Hearron. “It’s ridiculous.”

Attorneys also point to the many unusual aspects of the case that underscore how Paxton has disproportionately penalized the provider: For example, Rojas had to pay a $1.4 million bond and must wear a GPS ankle monitor. A friend of hers asserts that when she was initially arrested, she was “pulled over by the police at gunpoint and handcuffed” and that the officers “wouldn’t tell her what was happening.” During a March civil hearing, Rojas faced more than 200 questions from aggressive state attorneys.

Rojas’ case also lays bare Paxton’s desire to usurp civil and prosecutorial power. For instance, it is typically the Texas Medical Board’s role to seek an injunction to close medical clinics, not the attorney general’s, defense lawyers stress. And while the AG typically lacks the power to enforce criminal law, he can work around this barrier if a local district attorney requests it, as happened in Waller. While many of the DAs in Texas’ most-populous counties like Travis and Dallas have vowed not to criminally prosecute abortion care, Paxton was able to base this case in the domain of a more conservative district prosecutor: Sean Whittmore, who served in Paxton’s office from 2018 to 2020 within the Houston Medicaid Fraud Control Unit.

“When it comes to attacking abortion rights, Paxton has a long history of trying to abuse his power, when in reality he has pretty limited authority,” said Joanna Grossman, professor at the Southern Methodist University Dedman School of Law in Dallas. “But he does often get the complicity of the legal system by way of politically aligned judges and prosecutors.”

Even when a Texas court ruled in 2023 that Kate Cox, a Texas woman with a non-viable pregnancy, could undergo abortion despite the state’s strict bans, Paxton threatened to prosecute “hospitals, doctors, or anyone else” who would assist in providing the procedure with first-degree felonies. The anti-abortion AG has also successfully sued the Biden administration to fight against protections for Texas doctors who perform abortions in emergency circumstances. In 2024, Paxton filed a civil suit against a New York doctor for allegedly sending abortion pills to a patient in Texas, and he most recently filed suit against a Delaware-based abortion pill provider. Since 2022, taxpayers have footed at least $400,000 for Paxton’s legal war on abortion rights, according to open records requests filed with the attorney general’s office by the Observer.

Grossman said the litany of aggressive actions from Paxton is meant to create a climate of fear for healthcare professionals. Now stripped of her midwifery license and her livelihood, Rojas’ fate could have a chilling effect on other providers.

“The rule of law and the actual evidence aren’t as important to Paxton. With this case he’s more interested in sending a threatening message to anyone who is providing reproductive healthcare—especially to those in low-income communities: ‘We can come after you, shut down your clinics, and ruin your lives,’” said Grossman.

Evy Peña, director of advocacy with the Women’s Equality Center, a reproductive justice organization that focuses on movement-building in Latin America, said it’s “no coincidence” that the first person prosecuted under the Texas abortion law is a Latina midwife. Paxton’s public statements have been not only anti-abortion but laced with superfluous anti-immigrant descriptions.

“Ms. Rojas was serving low-income, Spanish-speaking patients and was a trusted resource for this already marginalized community,” said Peña. “State-led intimidation actions like this disproportionately impact vulnerable people, especially at a time when there is increased fear among immigrant communities.”

The lead investigator in the AG’s office on the Rojas case, Lieutenant Eddie Wilkerson, is also an enthusiastic Trump supporter who has made several “Blue Lives Matter” and pro-MAGA social media posts that include strong anti-immigrant sentiments, according to his LinkedIn profile. For instance, Wilkerson has said on his LinkedIn that the “only reason” non-U.S. citizens are counted in the U.S. census is to “keep Democrats [in] power” and suggested that “We should stop giving tax money to illegals.” Wilkerson also laugh-reacted to a comment that suggested “Just shoot them,” referring to undocumented immigrants who commit sexual abuse.

Wilkerson and the attorney general’s office did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

In its response last June to Rojas’ attorneys in the civil case, the AG sought to paint the midwife as an unlicensed doctor who performed illegal abortions. Rojas’ attorneys rebutted this, saying the state lacked any credible evidence of wrongdoing.

As the cases play out, Rojas’ clinics remain closed. Clinica Waller LatinoAmerica, a nondescript gray building, sits on a strip of land along Highway 290 in northwest Houston, flanked by a mix of residential homes and small businesses. With a faded storefront sign, the modest-sized building now hosts an unrelated mental healthcare provider. Nearly 20 percent of the largely rural Waller County population is uninsured, making the former clinic, which helped the low-income Spanish-speaking community through a range of medical services, a valuable—and missed—resource.

Rafael Silva, a nearby resident, told the Observer he visited the clinic when he cut his finger last year and received compassionate and timely care. His mother visited every year for her annual exam.

“They really helped us, and it’s strange that they are just gone now,” he said. “We don’t really understand why.”