If They Build It

Dallas' long and winding Trinity River Corridor Project.

With a kick from the muddy bank, our canoe slides into the Trinity River, a narrow strip of murky water canopied by looming black willows. We’ve put in at the Sylvan Avenue boat launch just north of downtown Dallas and will paddle 10 river miles to a takeout at Loop 12 in southern Dallas. It’s a clear, cool, mid-November day. No one else is on the river.

The purpose of this paddle is to traverse the site of the largest public works project ever undertaken by the city of Dallas: the Trinity River Corridor Project. A 1998 bond election approved the plan to make recreation, flood control and transportation improvements to the half-mile swath of scrubby floodplain bordering the Trinity as it flows through Dallas. More than a decade later, the project’s price tag has ballooned to more than $2 billion, its shape has shifted with the political winds, and only patches of progress have been made.

Depending on whom you ask, the project is either Dallas’ opportunity to reinvent itself as a “world-class city” or an example of the city’s weakness for business-driven policy and political bickering. Or both. In its current incarnation—known as the Balanced Vision Plan—the project envisions a central municipal park complete with lakes, paved trails crisscrossing the Trinity’s extant 30-foot levees, sports fields with solar-powered lighting, and a whitewater course. It encompasses the neglected Great Trinity Forest—more than 6,000 acres of undeveloped land just four miles from downtown. Levee projects, initially developed during the 1960s to protect impoverished and flood-susceptible areas south of downtown, have been resuscitated. A chain of man-made wetlands will absorb runoff from the well-to-do northern suburbs. Two “signature bridges” with soaring white arches will transform the Trinity-spanning freeways into iconic landmarks.

Then there is the so-called Trinity Parkway, the project’s key transportation component and its most contentious. The “parkway” is actually a six-lane toll road running nine miles along the river’s western levee, inside the floodplain. Everything about the road, from its proposed alignment to its estimated $1.8 billion price tag, has received intense scrutiny and generated near-evangelic defenses from its primary supporters: Dallas Mayor Tom Leppert (a former construction company CEO), the Citizens Council (a consortium of Dallas’ most powerful business interests), and the North Texas Tollway Authority, the state agency tagged to build it.

But the battle over the Trinity Parkway is about more than traffic congestion, tax dollars and construction timelines. To opponents, the toll road violates the New Urbanist principles that Dallas, like other cities nationwide, is otherwise embracing, including high-density development and alternative transportation. Backers say Dallas needs the road to keep the city’s commercial wheels rolling.

From the canoe, it’s clear the Trinity corridor needs help—a conclusion increasingly shared by frustrated city residents. The riverbanks are lined with plastic bags, discarded tires and tons of garbage. A rusted pipeline mangled by flood debris creates a logjam. An eddy swirling behind an abandoned pickup requires careful navigation.

Still, the Trinity provides a natural respite, no matter how abused. Blue egrets skim the surface with their wing tips. Perch drift under the bow. A family of plump beavers bursts from a burrow along the bank and splashes into the water. As we reach the outskirts of downtown, the Trinity snakes into an apparently forsaken urban wilderness. We paddle on.

A (Relatively) Brief History

In 1998, then-Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk (now President Barack Obama’s trade representative) presented voters with a $246 million bond proposal for the Trinity River Corridor Project. The proposition included “floodways, levees, waterways, open space, recreational facilities, the Trinity Parkway, and related street improvements,” as well as “other related necessary and incidental improvements to the Trinity River Corridor.”

As plans moved forward, then-City Council member Laura Miller, a former reporter, noticed that project funds were being steered toward roads at parkland’s expense. Under the direction of state highway engineers, the design sprawled into an eight-lane highway, leaving little room or money for open space and lakes. In 2002 Kirk left office to run for the U.S. Senate, and Miller was elected mayor. She began redesigning the corridor project.

Miller realized that to make the end result beautiful as well as functional, private funds would have to be raised. She tapped one of Dallas’ philanthropic dignitaries, Gail Thomas, to champion the cause. With Thomas collecting checks from the city’s elite, Miller could afford to hire top urban designers. Working alongside state highway and federal flood-control agencies, the designers crafted what Miller and Thomas dubbed the Balanced Vision Plan. Approved by the City Council in 2003, the plan represented a transition between what Dallas was and what it was becoming. The road remained, but as a six-lane tollway that narrowed to four lanes through downtown, with landscaping and public art to help it blend with the original plan’s water features, open space and recreational amenities.

In 2006—a year before receiving an urban design award from the American Institute of Architects—the Balanced Vision Plan came under renewed scrutiny. Newly elected City Council member Angela Hunt, from her perch on the city’s Trinity River Corridor Project Committee, found that the vision was blurring. The road was growing in size and expense. After the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers warned against placing the toll road too close to the levee, the road was redesigned, eating up another 40 acres of proposed downtown park space. Initially estimated at roughly $600 million, the toll road’s cost exploded to nearly three times that amount.

The road now represents more than 80 percent of the entire budget.

Hunt felt duped. Behind the scenes, she began meeting with battle-hardened environmentalists who had attempted to sink the project with two previous lawsuits. In spring 2007, Hunt organized a successful petition to put a referendum against the toll road on the upcoming fall ballot. The voters would decide if they wanted a highway in the Trinity River Corridor.

Troubled Bridges, Muddy Waters

As the battle over the design of Dallas’ central park and the toll road raged, oft-beleaguered city staff heading the Trinity River Corridor office chipped away at some of the project’s key components, many of which are evident during our float. The first of 14 bridges we pass beneath is the Continental Avenue Viaduct, supported by a row of arching concrete stanchions. Under the Balanced Vision Plan, the historic 1930s bridge will become a pedestrian walkway. Rising from the Trinity’s banks on the downstream side of the viaduct are the 40-foot concrete pilings of its replacement, the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge, one of three proposed bridges designed by award-winning Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava. This one would be named after the matriarch of Hunt Petroleum Corp., the bridge’s largest donor.

The Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge will connect the Woodall Rodgers Freeway, which cuts across downtown and currently dead ends at the Trinity, with West Dallas. The bridge will be the crowning achievement of fundraising efforts led by Thomas, who founded the Trinity Trust as the project’s private arm. At the Trinity Trust office, a 20-foot-long model shows the completed bridges. The intertwining cables of the bridge drape from a single steel arch soaring 400 feet above the river.

The bridge’s full splendor won’t be realized without logistical challenges. Calatrava estimated the bridge would cost $57 million, but the lowest construction bid came in at $113 million. The Italian company contracted to manufacture the main arch fell 10 months behind schedule, in part due to an international steel shortage, but primarily because engineers had trouble finding a way to build Calatrava’s design. Regardless, developers have begun snapping up land adjacent to the bridge-to-be.

We keep paddling. The river enters Dallas’ Great Trinity Forest meandering naturally, no longer channelized, and the levees tail off. Floodwaters here disperse into the surrounding lowland forest. As recently as 40 years ago, this was cleared farmland. During the 1970s, environmentalists cleverly applied the name Great Trinity Forest to this largest swath of urban hardwood in the nation (though the majority of the trees here are only a few decades old). The designation, they hoped, would keep the Corps of Engineers from grading and paving it into an additional floodway.

Eventually the land was placed under city ownership. Instead of channelizing the river to speed floodwaters downstream, the corps built a chain of wetlands alongside the Trinity to absorb runoff. Six wetland cells, complete with native flora and fauna, now sit alongside the river, with three more to come by 2010. Last year a bald eagle was spotted wintering at one.

Business as Usual

On Nov. 6, 2007, the referendum to re-site the toll road outside the floodway failed. A higher than expected 15.3 percent of eligible Dallas voters cast ballots. Fifty-three percent voted to keep the toll road within the levees. The pro-toll road group, steered by one of the city’s top political strategists, Carol Reed, raised more than $750,000 to defeat the anti-toll roaders, who spent just $100,000. Holding the referendum cost Dallas $2 million.

After the vote, the Dallas Morning News, which endorsed the toll road, and whose publisher is a member of the pro-business Citizens Council, ran this headline: “Dallas establishment wins again; grass-roots effort undaunted.” One of the paper’s most popular columnists, Steve Blow, wrote, “Let the dirt fly.” Despite Blow’s enthusiasm, there was no ribbon cutting. Newly elected Mayor Tom Leppert instead floated a fresh motto for the toll road project—”Beat 2014.”

Angela Hunt says even that is wishful thinking. “It used to be Beat 2013. I’m sure it will be Beat 2015,” she says. In her view, the road is the primary reason Dallas’ central park doesn’t yet exist.

She’s right. Everything dreamed up under the Balanced Vision Plan—a de-channelized Trinity, the faux-natural lake sheltered by tall, swaying grasses, the whitewater run, the riverside promenade, the downtown overlook and the miles of biking trails—none of it can proceed until there’s a road within the levees.

The tollway authority is moving ahead with a preliminary design plan that aligns the toll road with the levee’s western flank. The next step is a Corps of Engineers “408” review, its final approval of the road. Because of 2009 budget cuts, the funding for 408 reviews is being cut—a classic Catch-22.

The authority’s timeline calls for completion of the 408 process by the Corps and final approval from the Federal Highway Administration by the middle of 2010, at which point construction may, finally, commence. First, though, the authority must deem the toll road financially feasible.

“Before we commit to financing the toll road, we need to know the cost of building it,” says Sherita Coffelt, the authority’s spokesperson. Once the highway administration approves the final design—and the authority can determine construction costs—the authority will conduct a traffic and revenue study. The results will determine whether the toll road can generate enough revenue to justify building it.

What happens if it’s not financially feasible? “There are too many parties committed to this project for it not to be completed,” Coffelt says.

That’s why Hunt views the toll road as a quagmire its backers can’t walk away from. “There’s been so much political capital expended by people like Tom Leppert, who’s repeatedly claimed the toll road will be completed on time and at no additional cost to taxpayers, that it’s become increasingly difficult for them to extricate themselves from it,” she says. “There’s a fear among politicians and upper-level city staff that if they back off now, everything will be lost.”

Breaking Trail

We’re approaching the end of our float, the Loop 12 boat ramp, when we spot two shadowy figures standing beneath the bridge. They’re wearing quilted sports jackets and flat-billed baseball hats and drinking Coronas. We navigate a final rapid and drag the canoe up a concrete incline. The men smile and tilt their beer bottles. “Where’d y’all come from?” they ask. “See any fish? Lotta gar in there.” They want to know what’s upstream.

An older man appears from the margins. “Hey, a canoe trip!” he says, shaking hands with the beer drinkers before wandering off.

We’re loading the canoe onto the truck when a middle-aged couple shows up, circles the parking lot, then climbs out and begins halfheartedly picking up trash, glancing at us frequently. The older man is idling on the side of the road as we pull out. There’s no telling how many drug deals we just interrupted.

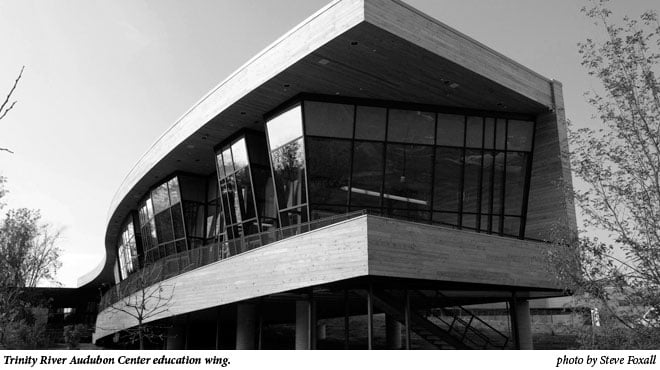

Had we paddled a bit farther, we could’ve exited the river at the Trinity River Audubon Center, the Trinity project’s interpretive cornerstone. More than 10,000 people visited the center during its grand opening last fall. Those who managed to get in marveled at the building’s award-winning, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design-certified architecture, including a rooftop garden and angled windows that deflect sunlight and minimize bird impacts. They wandered the 120 acres of open space and four-plus miles of handicap-accessible trails with Audubon guides describing the migratory birds circling above. At the push of a button, a scale model of the Trinity River floodplain demonstrated the effects of 100-year and 500-year floods.

“For the citizens of Dallas, the grand opening here was a symbolic moment for the Trinity River project,” the Audubon Center’s director Chris Culack tells me when I visit on a blustery December day. “The feeling was, ‘Okay, I can believe in it now.'”

Aside from the steady stream of school buses utilizing the educational facilities, Culack admits he doesn’t get many visitors from surrounding neighborhoods—though anyone living in the same zip code gets free entry.

“There’s not a lot being built down here in South Dallas,” Culack says. “Hopefully the Audubon Center can provide an impetus for more quality developments.”

A month or so after the canoe trip, I return to Dallas with my hiking shoes to tromp around the Great Trinity Forest with its savior and guardian, Casie Pierce. Pierce heads the nonprofit Groundwork Dallas, stationed in the Trinity Trust offices. As Pierce pilots her car out of downtown, she waves a hand at the strip clubs, liquor stores and bail bond offices bordering the Trinity’s levee.

“This is how we’ve treated nature in Dallas: Pave a road right next to the river and name it Industrial,” Pierce says. “Dallas is a business city. Progress here is defined in economic growth, often at the cost of the environment.”

While projects like the toll road and the signature bridges have soaked up millions, Pierce’s budget contains only $50,000 in city money. “The Great Trinity Forest is the redheaded stepchild of this entire project,” Pierce says, “even though we’re the ones actually doing work on the ground and within the community.”

We enter a neighborhood where steel bars barricade home windows and pull into a park where the play set has been burned down. The trail starts here. It winds beneath a canopy of leafy green trees and beside deep creek beds. It would be a great place to ride a mountain bike. Pierce says she’s working on allowing access for cyclists. (Perhaps the nation’s mountain-biker-in-chief, now a Dall

s resident, could

help.) After about a mile, we arrive at an overlook. The iconic Dallas skyline emerges from a sea of green treetops.

It’s a spectacular view.

Just below us, a bulldozer paves the way for Dallas’ newest DART transit line, which cuts straight through the forest. Pierce gazes scornfully at the site’s concrete retaining walls and chain-link fence. “This is, and always will be, an urban forest,” she says. “Emphasis on urban.”

On the way to a second trailhead, Pierce tells me about the Green Team, an effort to interest local communities in the forest’s future and build infrastructure. Local students participate in eight- to 10-week paid internships, cutting sustainable trails and rooting out invasive trees, but mostly picking up trash. The trail starts at a kiosk built by local Eagle Scouts and crosses a meadow before diving into the woods. A pedestrian crossing built by DART will eventually link the two trails, creating a six-mile hike from trailhead to trailhead.

Pulling out of the gravel parking lot after our hike, Pierce spots a truck parked on the side of the road. “Hey! What’s this guy doing?” she says, as a suspicious-looking man runs out of the trees, jumps in his truck, and takes off. He was probably dumping something. Getting the locals to embrace the forest, instead of destroying it, is Pierce’s biggest challenge.

The Traffic Jam

On March 22, 2007, Alex Krieger, one of the urban designers brought in to flesh out the Balanced Vision Plan, sent then-Dallas Mayor Laura Miller an e-mail expressing concern about fundamental changes to the Trinity toll road.

“The engineering of the road was proceeding as if it were a great big interstate highway instead of a parkway,” Krieger wrote. “Devoting MUCH, MUCH more attention to the design of the roadway—and making sure that it results in a road worthy of being part of great park and open space environment—is what I think is most immediately necessary.”

Krieger copied his design partner, Bill Eager. “The news from you, Laura Miller and Alex Krieger is disturbing,” Eager responded. “We had a deal to make this Parkway of a design appropriate to a park setting. We did not get everything we wanted but did get a commitment to no trucks, lower design speeds, reduced lane counts, improved shoulder design and a commitment to continuing emphasis on context-sensitive design.”

Krieger tells me, “If it’s a highway, there is no balanced vision. It will be tragic. This is where I felt I was being used. We always felt the highway guys were just playing along with us, hoping we would go away, then they would expand the road again.”

Krieger imagined a road that functioned within the context of the park first, and within the city’s transportation plan second, and recalls that at one point he told state Department of Transportation and toll authority engineers, “there are already 19 lanes of traffic through Dallas. If that’s not enough, 23 won’t solve your problem either.”

Eager was the real road guy on the design team, and while he wished for a curving thoroughfare reminiscent of East Coast parkways, his main focus was on providing relief for the “canyon” of traffic where Interstates 30 and 35 intersect, as well as access to the park.

The Dallas-Fort Worth region consistently rates as one of the most congested metropolitan areas in America. In an annual survey by Forbes magazine, the Metroplex moved from fifth to fourth nationally in 2009. While the area’s most severe bottleneck occurs at the intersection of Interstate 820 and Highway 26, in the vast suburbia linking the two cities, no one denies that the freeway interchanges just south of downtown Dallas suffer severe peak-hour jams. Speeds in the Canyon, Mixmaster, and Lower Stemmons interchanges average approximately 20 miles per hour for more than six hours a day.

The city’s solution is Project Pegasus, an ambitious plan to redesign the three interchanges by 2025. But Dallas planners say that Project Pegasus, like the corridor project’s parks and lakes, can’t move forward without the toll road. “The Trinity Parkway is a key reliever route for Project Pegasus,” says Rebecca Dugger, Trinity River Corridor Project coordinator and head engineer.

Complicating matters is the proposed inland port at the interchange of Interstates 45 and 20 in South Dallas. Plans for the port call for a 6,000-acre cargo and warehousing hub where containers delivered by freight trains from Houston, Mexico, and the West Coast will be dispersed via trucks. The Allen Group, the Southern California-based corporation developing the port, claims it will create 60,000 jobs and have a $68.5 billion economic impact on North Texas, an area desperately seeking development. For the port to succeed, it needs efficient roadways.

During the 2007 toll-road referendum campaign, the Allen Group contributed $50,000 to Save the Trinity, the organization supporting the toll road’s construction. The company’s owner, Richard Allen, personally donated $1,000 to the campaign of Dallas City Councilman David Neumann, chair of the Trinity River Corridor Project Committee. Allen Group representatives and Neumann didn’t return calls requesting comment.

The Trinity toll road’s current design calls for standard, 12-foot lanes instead of the 11-foot width more commonly used for parkways. “If you don’t have trucks, you don’t need 12-foot lanes,” Eager says. If truck traffic is allowed on the toll road, if and when it is built, “it would be a serious violation of our agreement.”

The Big Picture

Katrina changed things. After the levees broke in New Orleans, the Corps of Engineers instituted a higher set of standards for gauging the strength of a city’s floodways. When the corps applied the standards to Dallas’ Trinity River floodway, it failed 34 of 170 tests. Some items, like shrubs growing on levee walls, are easily fixed. Others, like the pier for the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge that “heaved and blew out” during construction because of sand beneath the floodway, are of greater concern. Water seeping along the concrete pilings and through the sand could cause the levees to collapse, resulting in catastrophic flooding downtown.

The corps’ levee rating—which states that Dallas is not adequately protected against a 60-year flood similar to one that occurred in 1990—doesn’t just complicate the prospect of putting a toll road in the floodway, it jeopardizes the entire project.

Following the 2007 toll road referendum, Mayor Leppert removed Angela Hunt from the City Council’s Trinity River Corridor Project Committee. Hunt vowed to continue working as a watchdog and constructive critic of the project. The Corps report prompted Hunt to declare on her blog, “The Trinity toll road is dead” and submit an op-ed to the Dallas Morning News outlining a Plan B for the Trinity River Project. Her Plan B calls for scrapping the toll road, fixing the levees, moving forward with the park and Project Pegasus, and investigating completion of an interstate loop from the inland port around the western edge of the city.

Despite a growing list of concerns—including diminishing revenues on state toll roads and the toll road authority’s inability to secure funding for the Trinity Parkway—Mayor Leppert and city staff continue to move ahead with the project.

Before I leave Dallas, I stop at the Trinity Overlook, a small, shaded pavilion at the east end of the Commerce Street bridge. Placards display attractive watercolors of the proposed park. A permanent binocular stand is free. When it opened on December 3, 2008, the overlook received sarcastic fanfare from local bloggers. An overlook? Of what?

In truth, there is little to see other than the trickling Trinity River, some scrubby trees and acres of patchy grass. I try to envision what the Trinity Park might eventually look like. I imagine a river free of debris snaking between the levee tops, pecan and oak trees interspersed throughout the floodway, and a string of lakes connected by paved and natural-surface trails. I try not to think about the toll road.

Because I don’t live in Dallas anymore, I can manage a semblance of optimism. The city’s residents aren’t so lucky. When I explain the premise of my story later that evening to a gregarious local at a bar in Oak Cliff, he rolls his eyes and gives me a firm handshake.

“Great! Come back in 20 years,” he says. “It’s gonna be beautiful.”

Ian Dille is a freelance writer in Austin.

The online version of this article was amended May 29, 2009, to correct a misidentification. Casie Pierce, of the organization Groundwork Dallas, was misidentified in the print version of the magazine as Cassie Taylor.