Freedom’s Just a Word

Texas is finally helping former prisoners. But can the smart-on-crime revolution survive budget cuts and a suspicious public?

Photos by Lance Rosenfield/Prime

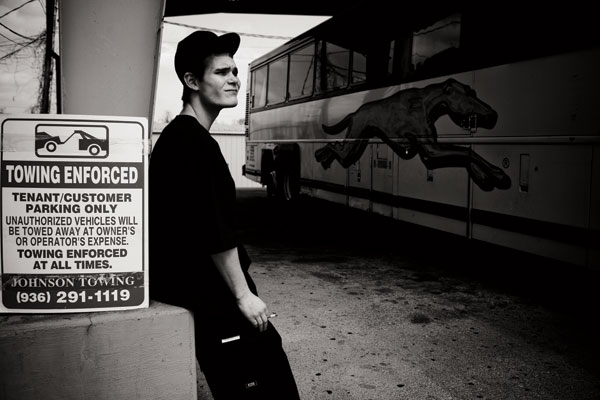

Former inmates board buses to Dallas and Houston after being released from the Walls Unit in Huntsville.

Every morning at around 10 a.m., dozens of prisoners are released from the Walls Unit in Huntsville. Family members and friends sit on benches across the street from the brick prison waiting for loved ones. Most have gone through this before and hope things will work out better this time.

On a bright September day, Observer reporters are visiting the prison to begin a six-month look into what prisoners face when they’re released. Rosalina Quejar is waiting for her 31–year-old son Samuel, who’s been in and out of jail since he was 16. She says he drinks and uses drugs. He fights a lot. He has three children with three mothers. He owes child support and tells her he might as well be locked up where he doesn’t have to worry about all that. “Sometimes I think we’re enabling him by taking care of him,” she says. “But I don’t believe in ever giving up on your children. Hopefully this will be the last time.”

Soon the prisoners file out, carrying clear plastic bags that hold their meager belongings. Some embrace family members. Others don’t have anyone waiting. The first to be released are “discharges.” They have served every day of their sentence and will not be answering to a parole officer. A slight, Hispanic man in this group walks briskly past. He doesn’t give his name, but once he starts talking, anxious sentences pour from him. He was convicted of capital murder and spent 23 years locked up. His eyes dart back and forth. He’s got $100 and a bus ticket. “How are we supposed to survive on this?” he asks. He says he has hepatitis from drug use, and few friends in Texas. “I just hope I don’t re-offend,” he says. He says he plans to go to Dallas and find friends. “They’re gonna want to get me high, get me laid,” he says. “The decision right there is no. I used to be strung out real big time. As far as drugs and prostitution, no.” His hands shake.

Soon the rest are released. They have to check in with parole officers in other cities, so most go to the bus station. This group is all male—women are released separately. Outside near some benches, young black men stand in a semicircle. They’re muscular and tattooed. One, Charles Farley, will let the Observer follow him for months as he tries to build a future.

As buses line up to take prisoners to Dallas and Houston, a few volunteers from the Restorative Justice Ministries hand out pamphlets with numbers for halfway houses, churches and treatment centers. Ministry Coordinator Bill Kleiber, an ex-offender himself, stands on a bench and gets everyone’s attention. “I got out ten years ago,” he says. “It takes us about two weeks to learn how to function out here. They treat us like babies in there. We don’t know how to make decisions. Then we a get little bit of rejection, boo hoo, I’ll never get a job. I’ll go get a beer. I’ll hang out with the old crew. They’ll make me feel better. Bam. Locked up. Don’t fall in the same pit I fell in to 10 other times, OK?” He opens a box of Bibles, distributes them and holds a prayer meeting in the parking lot while buses spew exhaust into the crowd.

Bill Kleiber of Restorative Justice leads a prayer at the bus station in Huntsville.

Bill Kleiber of Restorative Justice gives former prisoners money to buy hamburgers from a local restaurant.

With Kleiber are two men, Willie and James, both recently released prisoners. They are staying at the halfway house run by the Restorative Justice Ministry, and they come here in the morning to talk with ex-offenders. Willie, a former football player with a quick smile, once had an athletic scholarship at Sam Houston University—until a guy shot him at a party because Willie was talking to his girlfriend. The bullet lodged near his spine, and his football days were over. He lost the scholarship. It wasn’t long before self-pity led him to use and deal drugs. This is his third time out of prison. He’s been out a month, but he sounds confident he won’t be back. “It took this place to show me another way,” he says. “The change for me is knowing I can’t change it all myself.”

James is a study in contrast. He’s white and wiry and has a sly, self-deprecating sense of humor. He’s a 40-year-old motorcycle mechanic with a cocaine addiction. He’s been out of prison for several months and has started using coke again. He failed a urine test, ran out of money, and now he’s here. It’s been 12 hours since he last got high. “I know what’s next. I’ll start stealing,” he says. So he’s checked himself into the halfway house. “I hope something sinks in, something’s different this time.”

Six months later, the manager of the halfway house tells me that Willie is living on his own, working a steady job at a refinery. James is on the run from the law.

When former inmates go back to old habits, there’s a cost. Texans pay directly if they become victims of crimes, or in a more indirect way—tax dollars to build more prisons. For decades, the automatic response was to just lock ’em up again. Texas politicians sold themselves as “tough on crime.” In 1990, GOP gubernatorial candidate Clayton Williams ran a TV spot that promised to double the number of prisons and teach drug offenders “the joy of bustin’ rocks.” He lost to Ann Richards, but the prisons were built. Between 1985 and 2005, the number of prisoners in Texas increased 300 percent. The majority were in prison for nonviolent offenses.

Robert Bordelon waits to board a bus to Dallas after being released from the Walls Unit in Huntsville.

Texas politicians have realized the limitation to being tough and tough only. Incarcerating 5 percent of the state’s population is expensive, and without rehabilitation programs, you’re creating more problems when prisoners are released. Over the last decade, a group of politicians—Democrats and Republicans—has coalesced around a new approach that would send fewer people to prison. In 2007, the Legislature invested $241 million in probation, drug treatment and other diversion programs. Now, with the lawmakers looking everywhere they can for spending cuts, they have proposed eliminating many of these programs.

If the programs are cut, it would mark a return to a failing strategy. In 2007, the Legislative Budget Board estimated that Texas would need another 17,332 prison beds by 2012 that would cost over $2 billion to build and operate. That got lawmakers’ attention.

The data showed that county probation departments were sending 12,000 probationers to prison every year who hadn’t committed a new crime, but had “technical violations” like missing probation meetings or failing drug tests. Around 2,000 paroled prisoners hadn’t been released because they were waiting for a mandatory drug treatment program. Thanks to all those sentence enhancements, the state was paying to hold more than 20,000 nonviolent offenders convicted of drug possession and only 15 percent of those got treatment.

Republicans and their allies began embracing evidence-based practices that had been considered “progressive” or even “soft on crime.” The Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative, free-market think tank, began to collaborate with social justice groups like the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition. Perry got on board. Legislators like Rep. Jerry Madden, a Plano Republican, and Sen. John Whitmire, a Houston Democrat, cooperated to draft companion legislation.

Lawmakers realized that the only way to slow prison growth was to stop sending people to prison. In 2009, legislators renewed the 2007 funding and gave the Texas Department of Criminal Justice money for staff to help offenders get their lives together after prison. “If they become productive taxpayers,” Madden says, “then we won’t have to provide them free room and board in prison.”

The reforms paid off. Texas’ incarceration rates declined by 2009 for the first time in decades, by 4.5 percent. The state has already saved more than half a billion in prison costs. And here’s the kicker: In the period since the reforms passed, the crime rate has fallen. Now other states are sending delegations here to see how they can follow the Texas model—just as Texas may be on the verge of shutting it down.

Even with the reforms, it’s not easy for prisoners to get a second chance. The state might give them treatment that changes their mentality, but ordinary folks still have to rent them a place to live and give them a job. Not many people want to take a chance on former criminals.

Charles Farley, 27, was released in Huntsville after 11 years in prison. He spent the majority of his adolescence behind bars. He’s now being discharged after serving his sentence, which means a parole officer won’t supervise him. He’s on his own. At the bus station in September, Farley isn’t concerned about finding a job and a place to live. “Can’t nothing be harder than what I just came through. I’ll be able to make it. It won’t shake me up,” he says. He is determined not to return to his old friends and way of life. “The only person who stayed in touch with me was my father. That’s where my loyalty goes,” he says. Farley adds that he wants to walk down the street and not have to look over his shoulder.

A few weeks later, Farley is back in Austin, strolling by the gazebo on Lady Bird Lake. It’s warm and sunny. Joggers run by with their dogs. Farley’s looking good in a white polo shirt, new black baggy jeans and black and white sneakers. This idyllic spot is where his life took a turn at 16. “Me and my friends, we had just hit a lick on some guns, and we were sitting looking at the guns,” he remembers. Some people approached the gazebo and, seeing the kids with guns, ran to their truck. Farley and his friends followed them. As the truck pulled out, Farley rashly fired a shot at its back window. The truck spun away. The teens ran, but eventually the police caught up a mile away. Farley was charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. “So this is where my life went down the drain for 11 years,” he says.

Farley’s dad, Charles Farley Sr., says his son was “hardheaded. … He wouldn’t listen.” The young Farley admits he didn’t listen, but points to a reason: “When I was young growing up, I would see [my dad] this day, not see him again for a week or two. I’ll see him this year and not see him next year. It was a constant void.” His mom was a crack addict. His dad had relationships with many women. The young Farley found that with no guidance he had become what he calls “a man within myself.”

The opportunity for a normal childhood or adolescence was gone before he knew it. Farley started dealing drugs at 11 years old. He got his first car at age 13 with drug profits. He took care of his mom and sisters financially. His mom has always had health problems. “If it was me helping her pay for her medication, paying for a doctor bill, you know, keeping a little money in her pocket, helping my grandma pay her bills… I felt good about that,” Farley says.

All that ended when he was incarcerated. Prison was not a good influence on Farley. He continued dealing drugs. In every unit, he says, he had relationships with female guards. He would convince one of his “chicks,” as he calls them, to bring drugs in. After being in for two years, he got into a fight with a prison guard over a woman and received another four years in prison.

Now he’s out and a grown man, but with few legitimate connections and less money than he had as a 15-year-old. “Every corner I turn, there’s a temptation for something,” he says. One of the ironies of the criminal justice system is that it’s harder to make it straight after being in prison. Most job applications ask if you’ve committed a felony—and Farley’s got two violent ones on his record. Still, Farley says he’s willing to do “any type of work—just something to do every day.” Farley signed up with Project RIO, a program run by TDCJ and the Texas Workforce Commission to find jobs for ex-offenders. The program couldn’t find him a job. (Project RIO was shut down in February due to budget cuts.)

In December, Farley walks through his neighborhood of sun-faded trailers near the Austin airport. He says he has been feeling anxious and sleeps four to five hours a night. Staying indoors reminds him too much of prison. When he doesn’t have much to do, he uses a free bus pass from Goodwill to ride nowhere, just watching the scenery change. “When I think about it, I get upset,” he says. “I feel like here I am trying to be positive, and it ain’t working out like that. I’m just trying to do everything I can, follow the programs, but I’m just getting the run around.”

Selling dope again would be easy, Farley says. “It would just be me asking, I need such and such, and a certain amount of money.” He brushes that idea off. “Right now, and in the near future, I don’t even see it as a choice for me. It could easily be, but I try to stay focused.”

Later that month, Farley leaves Texas for North Carolina. He says he has a friend there, a music producer willing to teach him about the music industry. Farley has determined there’s no future for him in Austin. He promises to call, but there’s been no word.

Though lawmakers realize the state has a stake in ex-prisoners’ success, it’s not easy to change the system. For one thing, there is no one system. Prisoners are sent to county jails, state jails, state penitentiaries or to probation, each with its own rules and regulations. Local judges have their own sentencing philosophy, which can differ widely even within the same county. Forget about getting all these entities on the same page; they’re not even working from the same book.

In a sign of how formidable the barriers are, the Criminal Justice Department set up a re-entry hotline. The No. 1 call was not about jobs or housing or mental health or substance abuse—it was ex-offenders desperate for help getting a state ID. “We expect offenders to find housing and a job. That’s how you reduce recidivism,” says Dee Wilson, director of the department’s Reentry and Integration Division. “But if you don’t have documents, good luck.”

This problem absorbed much of Wilson’s first year on the job. As it turns out, getting ID cards for ex-offenders isn’t easy. The department isn’t sure of the identities of all of its prisoners. Some give fake names when they’re arrested, and the paperwork involved in verifying their identities is daunting. Wilson set up a contract to purchase Texas birth certificates and Social Security cards for prisoners before they’re released. Even that hasn’t solved the problem: Some prisoners weren’t born in Texas. Others weren’t born in a hospital. Some don’t know their mothers’ maiden names or their county of birth. Some prisoners refuse to sign releases allowing the Criminal Justice Department to obtain their documents. “I thought this was going to be simple to solve—until I got involved,” says Wilson.

Scott Galan, 26, waits at the Huntsville bus station after being released&nb

p;

In the past, recently released prisoners could be sent back to prison to complete their sentences just for missing a meeting with their parole officer or failing a drug test. The reality is, many of those offenders could make it on their own if they were given a second chance and connected with the right treatment program. So the Legislature directed the department to create “intermediate sanctions” for wayward parolees. These can include a couple months in jail, mandatory drug treatment and increased supervision, and has led to the lowest percentage of revocations in more than a decade. In 2004, before the reforms, around 15 percent of parolees were sent back to prison, or around 11,000 people that year. In 2010, 8.2 percent were revoked. That’s almost 5,000 fewer parolees going back to prison.

The Legislature also invested around $100 million in reforming probation, but that’s been harder because local governments control probation departments. Lawmakers provided new diversion options, including thousands of new beds in drug treatment programs, funds for halfway houses and grants to probation departments to implement evidence-based practices. But legislators couldn’t force judges and probation officers to use the new options. The percentage of felony probationers ending up in prison has decreased from 16.7 percent in 2004 to 14.7 percent in 2010.

Bexar County Commissioner Tommy Adkisson has made a mission out of improving the system there, but it’s slow going. He calls the jail “the jugular vein of the county budget” and has been working to get judges to change their practices. “Judges need to take ownership of the jail population,” he says. “Think of it like a garden that needs to be attended to every day. And let us help you. We’ll look over your docket and find people who don’t have to be in jail.”

Tony Fabelo is a researcher for the Council of State Governments and has analyzed the Bexar County probation department. He says the approach varied widely from judge to judge. “The best practice is to have a group of expert probation officers dedicated to assessing the risks and needs of each offender,” he says. “You look at mental health issues, substance abuse, employment, gang affiliation. By the time the person gets to court, the judge knows what kind of supervision is needed.”

The key is giving judges ways to supervise offenders without incarceration. Jail can be a disaster for some individuals. It can remove low-level offenders from honest employment and family, and confine them with a bunch of career criminals. Often these offenders need treatment for drug addiction or mental illness.

Dallas Judge John Creuzot convened one of the state’s first drug courts in 1998 after getting tired of seeing the same addicts come in and out of his court. “Now when they show up,” he says, “they already have a treatment program in place. We deal with everything from mental and physical health to housing to jobs. We tailor our responses to accomplish certain goals, whether it’s going to the doctor to get meds or showing up to work on time.”

Adkisson is attempting to create a more holistic approach to re-entry. “Eighty-one percent of our jail population has been there before,” he says. “It’s a prescription for insanity. But it sells to the public. The path of least resistance is to say we’ve got tough justice and all that BS. Instead, we want people coming out, working hard, paying taxes. Government can help do that, but it’s transformative stuff.”

Adkisson realizes government can’t do it alone. He’s convened a re-entry roundtable that includes local law enforcement, policymakers and service providers. Several other large counties are trying the approach, and the Legislature has created a statewide re-entry task force as well. Travis County’s re-entry effort succeeded by arranging job interviews before applicants are screened for criminal history. The hope is that private employers will follow the county’s example.

Now the Austin/Travis County Reentry Roundtable is trying to create permanent housing for the homeless and ex-offenders. But when a project called the Marshall Arms apartments was proposed, neighbors opposed it. Fact is, many people don’t want to hire felons or live near them. “There’s a lot of fear about hiring people with criminal backgrounds,” says Emily Rogers, planning coordinator for the Reentry Roundtable. “But when people are employed, they’re much less likely to recidivate.”

Often the people most willing to lend a hand are ex-prisoners, people who know how hard it is to get a second chance. At the Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Austin in January, former inmates have gathered for the seventh annual celebration of the church’s prison ministry. They discuss ways to make re-entry easier. The debate focuses on reforming the system (“The state doesn’t care if you succeed”) and the limits of government efforts to change lives. “I’m not saying you shouldn’t go to the Legislature,” says Rev. G.V. Clark, leader of Mt. Zion. “Go! But how long will it take you to change the system compared to how long it will take you to change you? Focus on what can be done rather than on what ain’t gonna happen soon. Someone in here made it.”

One of the organizers of the prison ministry, Pat Jackson, comes to the podium and asks for concrete ways to help ex-offenders. People suggest finding employers that hire ex-felons and sharing the list. Others say they’ll organize donation drives for food and clothing and money. Some promise support to former prisoners who can’t rely on their families.

One drizzly night in December, at a newly renovated halfway house in Southeast Austin run by Texas Reach Out Ministries, women sit on soft couches in their living room for a 12-step meeting. The director of the home, David Peña, is an ex-offender. He says he had a spiritual awakening in prison and has devoted the past 24 years to helping men and women who get out of prison reintegrate into society. Texas Reach Out has a 74-percent success rate. Success is measured by not re-offending, acquiring full-time employment, staying sober and moving into one’s own housing within two years.

All the women living here are recovering drug addicts, though no one would guess it. Amber, with blow-dried hair parted down the middle, a softball T-shirt and casual jeans, looks like an honor student. She works in a doctor’s office. Brittney, who works at a call center, is still in her business garb, her brown, curly tresses pulled tightly on top of her head. Two women in the meeting, Suzanne and Bree, have just left prison. Suzanne, 43, was on and off methamphetamine for 20 years and has been out for one month. She has long, straight brown hair pulled back with a headband and is missing some teeth. “A real hardcore issue that led me to my drug use was the guilt over my children and me not having them,” she tells the group. “Well, my son asked me a question that was pretty deep and deserving, and I handled it pretty well without going to dope. He asked me if I was going to stay out long enough to see him. I told him, knowing I was honestly telling him, ‘Yes.'” Tears stream down her face. “It was a big step for me, because if I didn’t choose to come here, I would have been high right now. So I just want to share that.”

Next to Suzanne is Bree Taylor. She has been to more than 10 rehabs and transitional houses, and been incarcerated twice. The last time she was released, she went back to using and cooking meth. Taylor says it feels good being around women like Amber and Brittney, who have found jobs and are earning back trust from their families, but she compares herself with them. “It’s a positive environment, but whenever you’re trying and you don’t get anything done, it’s hard. You see them come home, and they’ve been able to go shopping. It’s just like, oh man, I want to be there.”

A month later, Taylor is still looking for work. One day she drives to Texas Disposal Systems, a landfill where she is going to apply for an administrative assistant position. In her car, which her mom bought her, she says she has been depressed. Some days she doesn’t get out of bed. Fearful of facing rejection again, Taylor has put off going to the landfill for days. “When I first got here, I looked for a job so hard and tried so much, and everything is, ‘No, no, no.’ That’s real discouraging. I got real burnt out on it,” she says.

Even with support, Taylor has days when she wants to give up. “I’m through with drugs, but when it gets hard, you get back to thinking, well, if I was just out there running around doing whatever I wanted to, I wouldn’t have to worry about my rent or what this person thought or what that person thought, getting a ‘no’ to a job. You just don’t care,” she says. “It’s a hard life, but it’s easier.”

In a tight pair of pre-ripped jeans and too much eye makeup, Taylor pulls up to the building. “I don’t even want to go in there,” she says. She steps inside. Filling out the application, she wonders if she’ll have to put down anything about her criminal history. Then there it is, on the last page. Back in her car, she feels relieved. She opens a fresh pack of Marlboro Reds, lights one and takes a long drag.

It’s tough going, but her perseverance pays off. In January, Taylor gets a job at a call center. And by March, she says she’s still clean and no longer depressed.

Texas is about to fall into a familiar pattern. In the early decades of the 20th century, Texas lawmakers pushed for reforms that would educate prisoners and pay them for their work. But the state ran out of money for the programs. “It’s a shame,” says Robert Perkinson, author of Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire. “Texas has movements for reform that are stronger than other southern states, but they’re always smashed on the altar of fiscal conservatism.”

This year, when the House and the Senate issued their proposed cuts to the Department of Criminal Justice at the start of the current legislative session, they cut the biggest chunk out of the diversion programs. If judges can’t sentence people to programs because of long waiting lists, they’re likely to send them to prison. With the state facing a $27 billion shortfall, the proposed cuts are not always logical. It’s politically easier to end a treatment program than shut down a prison.

The House bill would cut 21.7 percent of funding for probation, which includes diversion programs and treatment alternatives. The Senate bill was less drastic: It suggests cutting 12.8 percent from probation programs. The biggest share of the criminal justice department’s budget—operating prisons—was left virtually untouched. Out of its 114 prisons, the proposals suggested closing one.

The budget cuts are merely preliminary, and there are signs that lawmakers are looking for alternatives. According to Ana Yañez-Correa, director of the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, there have been 11 bills filed that could save $250 million from TDCJ’s budget—enough to keep the diversion programs intact. There’s a bill that would divert low-level drug offenders directly into treatment programs. And the legislators are even considering doing what was once thought unthinkable—letting people out of prison and closing down units. Sen. Whitmire, the Senate Criminal Justice Committee chair, has suggested releasing 3,000 foreigners in jail for nonviolent crimes and deporting them. Legislators are also suggesting releasing elderly and infirm prisoners. If prisons can be closed, the department could still slash its budget without shutting down the treatment programs. The alternative, says Yañez-Correa, is “more victims and more people behind bars.”

Rep. Madden, who is chair of the House Corrections Committee, was one of the architects of the reforms. He remains optimistic that lawmakers can save the treatment and diversion programs and keep lowering the number of Texans behind bars. After all, putting someone in prison costs ten times more than supervising them on parole. As he puts it, “When it comes down to it, would you rather spend money on prison beds or educating kids?”