Building D.E.E.P. Bridges

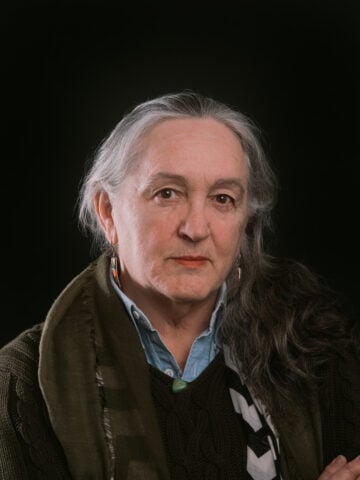

Houston's Deborah Mouton is creating a legacy, a mythology, and connections between cultures and artistic worlds.

A version of this story ran in the July / August 2023 issue.

It’s a Thursday in mid-May, and Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton, Houston’s multitalented poet laureate emeritus, is busy. She’s getting ready for an event the following night, a collaboration involving herself, jazz drummer and composer Kendrick Scott, and the Harlem String Quartet. They’re honoring the Sugar Land 95, African-Americans who died as convict laborers and whose remains were found in 2018 during excavation for a construction project in Sugar Land, just west of Houston.

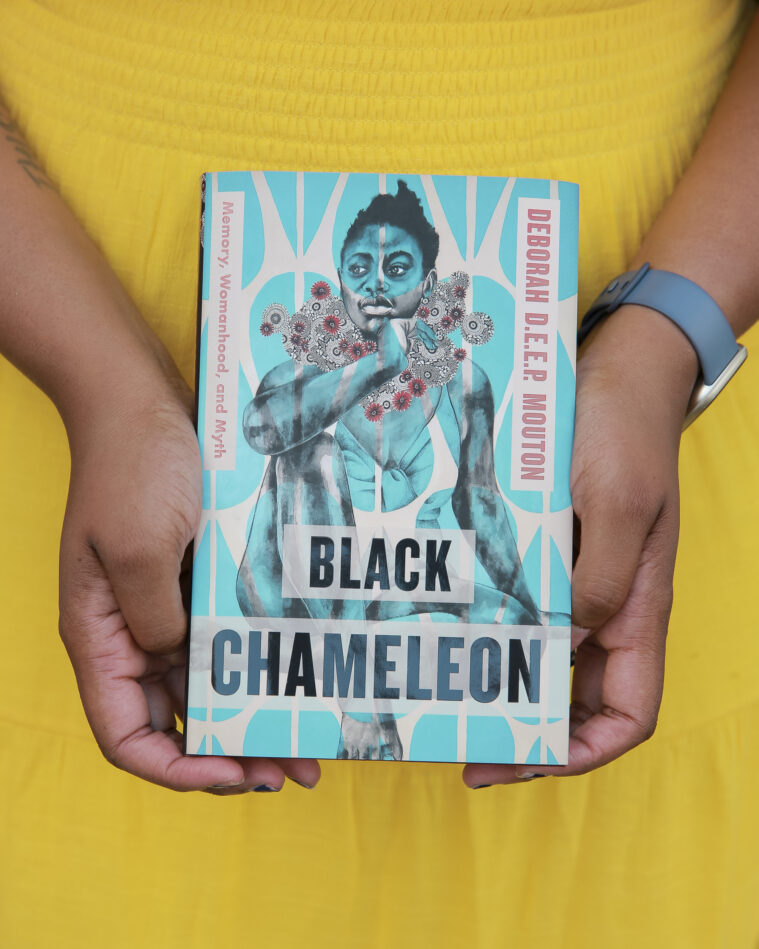

After that, she’s off to New York for rehearsals of a new opera, She Who Dared, about the women, including Rosa Parks, who helped desegregate the Montgomery, Alabama, bus system. Mouton wrote the libretto and Dallas composer Jasmine Barnes did the music. The rehearsals culminated in a public workshop on May 31 at the American Lyric Theater in New York. Next up for Mouton: a U.S. book tour in support of her new mythologized memoir, Black Chameleon, then a festival, then the European leg of the book tour.

Her schedule and her energy leave Mouton’s friends shaking their heads. “It’s just mind-blowing,” said Robin Davidson, another former Houston poet laureate and an early editor on many of Mouton’s projects.

Kate Martin Williams is the executive director of Bloomsday Literary, the nonprofit independent press in Houston that published Newsworthy, Mouton’s first book of poetry. Williams said she and Mouton sometimes meet for breakfast, and she will ask the writer about the most recent thing she’s working on. When Mouton stops for breath, Williams said, she tells her friend, “No, you just told me about five things.”

Mouton, 38 and the mom of two young kids, says she couldn’t do it all without her “magical super-supporter” husband Joshua, her mother, and friends—“a great village” helping her. That, plus a huge family calendar that shows her kids who is going to be home when—and an online document.

“I have a Google document with all my ideas,” she said. “So when I do get a breath, I can go back to that” and start working on yet another project.

Growing up in California, she said, someone was always telling her that she wouldn’t be able to make a living by writing, regardless of which kind of writing she did. “I said, ‘OK, but what if I do them all?’”

someone was always telling her that she wouldn’t be able to make a living by writing, regardless of which kind of writing she did. “I said, ‘OK, but what if I do them all?’”

The dedication in Black Chameleon seems to refer to that idea of adaptability. “For those who have had to shape-shift, code switch, and camouflage just to survive,” it reads. The book is subtitled “Memory, Womanhood, and Myth,” and she describes myth-making—reinterpreting your own story—as an important part of her life, especially as a Black woman in this country.

Mouton said the book began as a collection of the stories of her family. “I’m the griot, the storyteller, I had a need to write them down,” she said. But 150 pages in, “it still wasn’t feeling like a book.” A friend asked her about the mythology she grew up with. “I had no idea,” Mouton said. So she decided to “work backward from what I have become, to reverse engineer” her life and her family to delve into that mythology. And so the book includes segments about things like “how Black women learn to have eyes in the backs of their heads,” and treats Love and Death like characters.

Black Chameleon is doing “fairly well,” Mouton said. It got a favorable review in the New York Times and was picked as one of the top 30 books by Cosmo this year. But, she said, success in book sales is “very elusive.”

If Mouton’s literary tree is many-branched these days, it remains rooted in poetry, thanks to a teacher who talked her into it. In school, she said, “I was horrified when I tried to do spoken word.” But then her teacher explained there was a contest, and her competitive young self thought: “I’m going to get a trophy for writing? OK!” She went on to become one of the world’s top female spoken-word artists; videos on YouTube attest to her eloquence.

In Black Chameleon, she seems to be channeling that power. “I got it honest, this tongue,” she writes at one point. “This neck roll, this lip pop, this hand clap, this way to make a simple tale a dramatic feat.” The price of such eloquence, when she was growing up, was sometimes having her mouth washed out with a bar of soap. A reminder, perhaps, that talent doesn’t make it all come easy.

After the pandemic, she struggled with anxiety over being in rooms full of people. The stage “is definitely not a place where fear doesn’t live,” she said. “But I can be scared and still do it.”

Her skills at performance poetry opened many doors. And Mouton, in turn, has opened doors for others, including by broadening the audience for spoken-word poets and showing that slam poets can get published, even internationally.

Written poetry these days can seem inaccessible. Most poets don’t draw huge audiences or large incomes. On the other hand, performance poetry tends to be much more of a popular artform.

Poetry doesn’t have to be inaccessible, Mouton said. “It’s the ways we have treated it historically” that have made it so. In past centuries, poetry was storytelling—the way everyone heard and enjoyed lovely and meaningful writing. “We’re getting back to letting it be accessible,” she said.

Newsworthy, published in 2019, is a slim volume of poems that, line by line, are very accessible. No fifty-cent words or difficult constructions; nothing scary here. Except, everything. Toward the end, it becomes hard to go on to the next poem. This is Mouton’s way of coming to grips with white supremacy, police brutality, the seemingly unending stream of Black bodies ground under the wheel of those pressures, and the media coverage that often makes things worse.

“As a Black woman traversing America … it’s about my own experience with authority and the abuse of it,” Mouton said. “The ways the media goes about reporting it.” Watching someone die in a viral video has almost become entertainment these days, she said, and she won’t take part anymore. And she thinks the news media has gotten worse, not better, in its depictions.

Newsworthy is generally chronological, Mouton said, going back to the 1991 beating and tasing of Rodney King by Los Angeles police, which she remembers as a child, to the death of Sandra Bland, the 28-year-old Black woman found hanging in her cell in Waller County, three days after a state trooper followed her while driving, repeatedly speeding up to crowd her bumper, until she pulled over to let him pass and he stopped, wrestled her to the ground, and arrested her on trumped-up charges. The poems relate to other incidents of police violence, malfeasance, or terror of police violence in the years between those two tragedies, often as viewed or experienced by the members of a Black family. But the poems are also ordered in another way: Each carries, in small type at the top of the page, a notation of mileage—that is, the miles away from Mouton’s home that something happened, the numbers large at first, then dwindling and dwindling, to 38.5 miles (the distance from Sandra Bland’s death site to “outside my back door,” Mouton said) and then to “even closer” and finally to “here.”

“It’s what it means to live in these times,” she said. Her performance of the poem “Open Season,” captured on YouTube video, is powerful. “Gas Station Libretto” (“a conversation between a gun and the people on either side of it”) is equally striking. The book was a finalist for the 2019 Writer’s League of Texas Book Award in poetry and a runner-up in the Texas Institute of Letters award for a first book by a poet.

Williams said her publishing house sought out Mouton based on the recommendation of a local bookstore manager. The poet “hadn’t been able to get any traction” with other publishers on Newsworthy, possibly because of her slam poetry connection. But Bloomsday is smaller, with “a little more liberated outlook,” Williams said. “We thought we could translate her performance to the page.”

Mouton’s ability to adapt her poems from performance to print is important, Davidson said. “They work lyrically on the page.” The mileage numbers moving the reader closer and closer to the incidents show that such deaths are “internal to who we are, all of us, as human beings,” she said. Mouton’s work is “very much revered by high-profile literary folks in our state.”

That work was what led the Houston Grand Opera (HGO) officials to reach out to the former laureate with a proposition—could they blend spoken word and opera? Mouton had already done things like touring with a gospel choir and, as laureate after Hurricane Harvey, appearing with organizations from the Houston Ballet to the Houston Rockets to inspire a weary public to hang in there. “Moving into my laureateship in that new way showed me that poetry and my abilities were limitless,” she told Texas Monthly.

Now, HGO helped her learn about writing librettos, so she could collaborate with composer Damien Sneed on a chamber opera about the life of Marian Anderson, the brilliant contralto singer who fought racism in the mid-20th century by, among other things, giving a famously successful concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial after the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow her to sing in Constitution Hall. The result of the collaboration was Marian’s Song, the 2020 premiere of which the Houston Chronicle called “a fiery blend of history and music” with Mouton’s “quietly confrontational” libretto urging listeners to think about their own responsibility to keep up the fight. That opera included a contemporary, fictional character—a young woman who speaks only in rhyme, portrayed at the premiere by a local slam poet. In those sections, the Chronicle reported, the music “took on the repetitive urgency of a news bulletin.” Or maybe of a Newsworthy poem.

Around that time, Mouton had approached another Black woman named Anderson who also holds a special place in Black history: She asked retired Houston Ballet star Lauren Anderson, the first Black principal ballerina of any major company in the country, if she would collaborate on a memoir. That book is still in progress, but in the meantime, the two, along with Barnes (also Mouton’s partner on She Who Dared) produced another offspring last fall: “Plumshuga: The Rise of Lauren Anderson”—what Mouton calls a “choreopoem,” portraying not only Anderson’s triumphs, but her struggles with addiction and her recovery. Performances featured a full dance company, with a “Poet Lauren” reciting Mouton’s lyrics and a “Dancer Lauren” bringing Anderson’s memories to life.

Davidson is definitely a fan. “Oh my God, it’s so moving,” she said. “I don’t think there was anyone in the audience who didn’t weep.” She said Anderson and Mouton have great chemistry, and she expects the memoir to be a hit.

“I don’t think there was anyone in the audience who didn’t weep.”

In fact, Davidson expects more from Mouton on many fronts. “She’s just at the beginning of things,” she said. When Mouton’s children are a little older, Davidson said, she’ll likely have time for even more. In the meantime, Mouton said, no matter where she is, she sings her kids to sleep every night. They go to local performances together. And following in their parents’ footsteps, son Julius is the storyteller—“he’ll talk your ear off”—while daughter Olivet is the poet and visual artist, like her dad Joshua, a graphic and visual artist.

Mouton, of course, already has other projects in mind. Maybe something “more episodic,” like a TV series, she said. She’s already working on ideas for her next poetry book. The opera She Who Dared is still in its beginning stages, waiting to see if an opera company decides to put it on. And oh yes, she’s also working on a novel.

All these opportunities, and what she’s made of them—does it feel like her world is opening up to larger and larger views? Not quite, she said. “It’s more like leveling up in a video game. I acquire skills so I can fight bigger bosses. By the end, I can do things I never thought I could do.”

Davidson sees Mouton, with her talent and energy and her projects that uplift and memorialize Black Americans, as being one of the forces working to reconstruct the narrative of this country. “She is bridging the gap; what have been disparate cultures are beginning to be [combined].”

Mouton said it’s exciting to watch her works being performed by others, and “at heights I never imagined.” She’s also consciously building a legacy, a body of work. “That’s why working in these grander ways is so good,” she said. “I had a knee replaced last November,” and that made her think about “how to make space in my work to make it last.” With a catalog of work and a unique skill set, she said, despite those warnings she got all those years ago, “I will be able to live on my art.”