No Refuge

Five years after the infamous raid on the FLDS compound in Eldorado, questions remain about the state's handling of the case and the safety of the children.

A version of this story ran in the August 2012 issue.

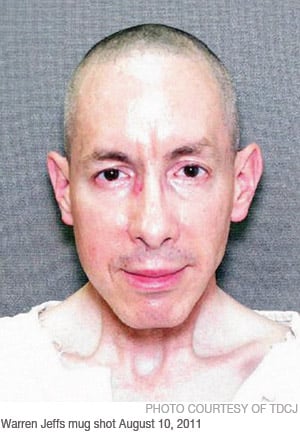

In 2008, Texas authorities raided the Yearning for Zion ranch outside Eldorado and discovered that a fundamentalist, polygamous Mormon sect led by Warren Jeffs had been “spiritually” marrying underage girls to adult men. The state took custody of more than 400 children for two months in what became the largest child custody battle in U.S. history.

When it was over, all children were returned to the sect, and no parents lost custody of their kids. State officials claimed victory, saying they improved the sect’s culture by ensuring that members no longer would sexually abuse girls through underage “spiritual” marriage. But as we approach the five-year anniversary of the raid, two questions linger: Did the state really protect the children, or leave victims in the care of abusers? And does anyone know where those children are now and if they are safe?

On November 25, 2003, while traveling from Utah to Colorado, Warren Jeffs told three women in his sect about the special purpose for which God had chosen them. Jeffs is the “prophet” of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (FLDS). The Mormon sect—which is estimated to have 10,000 members, mostly in Utah, Arizona and British Columbia—practices polygamy, a custom the mainstream Mormon church gave up in 1890. Jeffs often made divine pronouncements, which usually accompanied new rules for sect members to follow. As with much of what Warren Jeffs told his followers, those pronouncements were meticulously recorded in journals.

Jeffs explained to the women that the FLDS needed to establish “places of refuge,” according to the journals. He felt the group wasn’t safe in its traditional strongholds in Utah and Arizona. (Fear of persecution is nothing new to the FLDS. Many members still talk about how Arizona authorities raided the sect in 1953 for practicing polygamy.) A few months earlier, in August 2003, a Utah police officer who was also an FLDS member had been convicted of bigamy and sexually abusing a teenage girl. There were also rumblings that attorneys general in Utah and Arizona were joining forces to crack down on crimes committed by the FLDS, such as underage, legally nonbinding, “spiritual” marriages.

In places of refuge, Jeffs felt, his followers could live free of intrusions by outsiders. However, not everyone would get to enjoy the privilege. As Jeffs explained to the women, “The only ones allowed in these places of refuge are those named by revelation, the Lord telling me who can go there, and your names were given to me, and that is why you are going with me,” Jeffs said. “So consider that you are called by Heavenly Father to do a special work, to help build Zion.”

Jeffs had a particular place in mind where that “special work” would take place. It was a 1,400-acre patch of desert outside the West Texas town of Eldorado, a place of refuge he designated “R17.” There, the FLDS would create a community from scratch, which entailed building a concrete plant, an enormous temple and residences. According to a dictation dated May 5, 2004, Jeffs told followers that a motor home was ready to transport members to R17. Again, Jeffs was particular about who would be aboard. He was “pruning,” as he put it, hand-selecting the most devout and obedient men, women and children.

Unlike in Utah and Arizona, Jeffs didn’t seem worried that those living in R17 might encounter legal trouble. In fact, he was so confident that the state of Texas would leave the FLDS alone, he instructed a member to keep FLDS lawyers away from R17, “where they will bring a compromise to that mission.” On January 1, 2005, Jeffs was on hand to consecrate the site, which he named Yearning for Zion. It must have been a glorious moment for the religious leader who foresaw a place where girls would learn to “keep sweet” and boys would become “priesthood holders.”

What Jeffs did not know was that he had moved his most devoted followers to a place where locals would keep a sharp eye on them.

As the FLDS constructed buildings, a pilot flew over the property and reported on the group’s activities, casting doubt that the FLDS was setting up a hunting retreat, as sect members had claimed. The Schleicher County sheriff began working with an FLDS informant, who helped him understand the group’s customs. Alarmed by reports that the sect engaged in underage marriage, a state lawmaker passed a bill raising the age of marital consent from 14 to 16.

Jeffs was right that authorities back home were after him. In 2007, he was convicted in a Utah court of being an accomplice to rape. The conviction was overturned, but Jeffs was soon transferred to a Texas jail to stand trial again. (In 2011, a Texas jury would convict him of sexually assaulting two girls, ages 12 and 14.)

In April 2008, while Jeffs was still serving time in Utah, Texas law enforcement officers and Child Protective Services workers raided the Yearning for Zion ranch and found what they believed was evidence of child sexual abuse. State officials moved quickly to remove more than 400 children from the ranch.

The FLDS waged a vigorous public relations and legal campaign to win the children back. The battle that ensued—waged by state attorneys and lawyers hired by the FLDS—became the largest child custody lawsuit in U.S. history. The entire investigation ended up costing the state $12 million.

The Department of Family and Protective Services, which includes Child Protective Services, states that the investigation was a success. But many other people closely involved with the investigation wonder whether the agency lived up to its charge to protect children from abuse and neglect.

A six-month Observer review of the raid and its aftermath has found that the department—in the face of public and political pressure, and stung by several critical mistakes—closed nearly all the children’s cases just months after the raid, even though cases involving as many as 30 children contained clear evidence of sexual assault due to underage “spiritual” marriage. The agency didn’t seek to terminate any parent’s custodial rights, over the strenuous objections of its own attorneys. This means even Warren Jeffs, who is serving a life sentence for sexually abusing girls and has been accused of raping boys, retains custody of his hundreds of children.

State officials claim the children are safer now than before the raid took place, yet it’s impossible to verify this assertion, because caseworkers stopped monitoring the ranch in 2009. In fact, no one outside the FLDS seems to know where the children are—after the raid, Jeffs moved some of the families to other states—or what’s going on inside the Yearning for Zion compound. Jeffs continues to come up with “revelations” and control his followers from prison. Without state oversight, it’s even unknown if spiritual marriages of young girls have secretly resumed.

Did Warren Jeffs manage to establish an FLDS place of refuge in West Texas after all?

The Raid

On March 29, 2008, a domestic violence hotline in San Angelo received the first of a series of calls from a female who referred to herself as Sarah Barlow. “Sarah” claimed to be 16 years old and the seventh wife of an FLDS member living at the Yearning for Zion ranch. Later, it would come to light that the caller wasn’t a member of the FLDS church, but a mentally ill woman in her 30s who had a history of making false reports.

But authorities were unaware of the ruse, and so, on April 3, law enforcement officers showed up at the gates of the Yearning for Zion ranch with a warrant in hand. After sect leaders failed to bring out “Sarah Barlow,” the officers entered the property along with a team of investigators and caseworkers from Child Protective Services. The girl in question was not found, of course, but authorities did see what looked like many “Sarahs”—girls who appeared to be underage with young children. Some were visibly pregnant. The officers got a second warrant that permitted them to search for any evidence pertaining to child abuse. While officers collected computers, photographs and other evidence, caseworkers interviewed teenage girls. The girls kept changing their stories about their ages and which children were theirs.

The caseworkers had seen enough. Under Texas law, it is illegal for anyone to have any kind of sexual relations with a child under the age of 17. (The marital consent law allows girls who are 16 to get married with their parents’ permission, but that law did not apply to any of the girls designated as victims in the FLDS case.) Over the course of a few days, caseworkers did what they usually do when they suspect that children are victims of abuse and that the adults caring for them are not protective: They removed the children from the home. In this case, the children totaled 439, and the “home” was a 1,400-acre community with one street address.

The children were taken to temporary shelters. Despite the unusual circumstances, all seemed to be going according to protocol. Then the Department of Family and Protective Services made the unusual decision to allow the mothers of children under the age of 12 to accompany their kids. (Typically, adults in this kind of situation are considered alleged perpetrators and are kept away from the alleged victims.) It was a decision the department would soon regret.

By April 14, the mothers and children were being housed at the San Angelo Coliseum. Large trucks containing laundry facilities and showers and mobile clinics, the kind normally used in natural disasters, were brought in. Allowing the mothers to accompany young kids turned out to be a terrible mistake. Even though it was against the rules, the women snuck in cell phones, which allowed them to communicate with their husbands and attorneys. When children were identified with wristbands, the mothers removed them or wiped off the information. The women posted “keep sweet” signs on the walls, a subtle reminder to girls not to speak against the sect. When doctors examined the children for signs of abuse, they did so only “from the neck up,” as one physician put it, because mothers objected to their children being undressed.

Meanwhile, the Department of Family and Protective Services filed its initial pleadings before Judge Barbara Walther, whose district court has jurisdiction over child welfare cases in Schleicher County. The agency stated that the FLDS had engaged in a “pervasive pattern and practice” of forced marriages and sexual abuse. Caseworkers reported that girls told investigators that “no age was too young for marriage” and that “the prophet determined when and whom a girl should marry.” At an April 17 hearing, Walther determined that the children should remain in state custody on a temporary basis and ordered DNA tests of all FLDS members. The children were to be moved out of the coliseum, and into foster care homes and facilities across the state.

A Media Storm

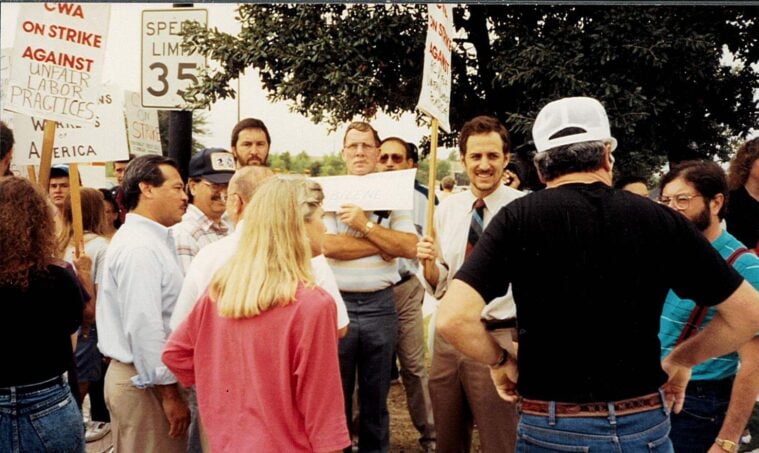

As news reports circulated that hundreds of children had been removed from a religious community in West Texas, state officials faced fierce criticism. One conservative blogger called Judge Walther the “wicked witch of the west.” Conditions at the temporary holding facilities were not pleasant. There was overcrowding, children became ill, and the bathrooms kept backing up. The National Coalition for Child Protection Reform accused Child Protective Services of treating church members like “detainees at Guantanamo.” FLDS members fomented the outrage, accusing the state of violating their religious rights. They allowed the media to interview FLDS mothers, an openness previously unheard of. In front of the cameras, teary-eyed, handwringing mothers, wearing traditional, pastel-colored long dresses and old-fashioned pulled-back hairdos, appealed for public sympathy by describing how the state “ripped” their children from them.

Meanwhile, high-priced FLDS lawyers were doing their best to intimidate state officials. (Many were surprised that the FLDS had enough money to hire the attorneys, but it turned out the group possessed holdings estimated at $100 million.) Rod Parker, representing the Salt Lake City law firm of Snow, Christensen and Martineau, sent Carey Cockerell—commissioner of the Department of Family and Protective Services—a letter saying the firm was “concerned” that the agency had violated its clients’ constitutional rights, and warned the agency not to destroy any evidence collected and to preserve the names of every individual working on the case. The agency was being put on notice that not only did the FLDS have the means to hire a high-powered law firm, the sect was ready to sue the agency if it made a false move.

By this point, state officials, the media and the public were beginning to get the idea that the FLDS was not a quaint, old-timey religious sect but a well-organized and well-funded group determined to do whatever it could to prevail in court. Yet there was still a great deal more to learn about the FLDS. Namely, that the sect’s abuse of children did not stop at underage “spiritual” marriages. For some children, according to former members and court records, abuse and neglect had become a way of life.

Abuse in the FLDS

It’s only recently that the public has gotten a glimpse into what it’s like to grow up in the FLDS church. For decades, the sect has kept out of the public eye and for good reason. Members have been accused of a host of crimes, from bigamy to child sexual abuse to welfare fraud. Like other fundamentalist Mormon organizations that practice polygamy, the FLDS claims it remains true to the teachings of Joseph Smith, the polygamist who founded the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. While Mormon doctrine does not condone underage marriage, an accompanying text to the Book of Mormon known as the Doctrine and Covenants discusses the spiritual need for a man to marry many virgins.

For nearly a century, the majority of the FLDS has lived in the twin cities of Hildale, Utah, and Colorado City, Arizona, an area that has traditionally been called Short Creek. The sect is isolated and largely self-sufficient. The community grows much of its own food. Children are educated at home or in FLDS-run schools. Most public officials in Hildale and Colorado City, including much of the police force, belong to the sect. Outsiders who venture in soon find themselves being tailed by FLDS patrols.

Obedience is the watchword of the FLDS. Everyone, men included, is compelled to obey the “prophet,” the head of the group, who is believed to speak for God. Women not only must obey their husbands but depend on them for salvation, because only men, as members of the “priesthood,” can “exalt” their wives and children to the Mormon version of heaven, known as the Celestial Kingdom. Children are raised to be obedient to their parents and especially to their fathers. Girls are taught to “keep sweet.” That is, to appear innocent and kind and to never argue. Like many authoritarian religious communities, FLDS members fear and mistrust outsiders, whom they call “gentiles.” This includes governmental agencies that aim to protect children from abuse, such as police and Child Protective Services. When someone in the group is found to be abusing a child, former members say, chances are that no one will report it.

With so much emphasis on obedience and patriarchy, and so little accountability, abuse in FLDS households can become severe and continue unabated. Joseph Broadbent, now 23, says he left the sect in Utah when he was 17 to escape his father’s brutal abuses. “My father was born an angry man. He always took his anger out on us kids,” Broadbent said. When his father had a bad day at work, he would “come home and not just give a slap across the face. It was grabbing a push broom or shovel and breaking it over your back.” Yet no one reported the abuses, Broadbent said, even though neighbors watched his father “kick my ass around the yard.” Though his mother was “scared to death” watching her husband brutalize his children, she never intervened. “Mothers can’t question husbands,” Broadbent said.

Testimony at a hearing during Texas’ investigation revealed that some FLDS members have waterboarded infants to make them docile. On August 18, 2008, Carolyn Jessop, who escaped the FLDS with her eight children in 2003, testified that her ex-husband was “dangerous for children to be around.” Jessop described one incident in which her husband became angry with their baby Arthur for not eating solid food. Jessop said her husband spanked the baby “very hard” until Arthur was “screaming out of control.” Then he took the infant into the bathroom, where “he turned the tap on and held Arthur, face up, under a tap of running water,” according to court records. Jessop continued: “Before Arthur had caught his breath, he began spanking him again. The second time he put Arthur up under the tap of running water, Arthur’s face was blue.” Jessop said the waterboarding and spanking cycle continued for about 40 minutes, according to court records. Asked why her husband did this to his child, she explained that the concept was to instill in babies “a severe level of fear for their father or authority.”

While FLDS leaders have always expected obedience from worshipers, no leader has tested members’ devotion like Warren Jeffs, who took over as prophet in 2002. Jeffs has issued dictums that affect every member of every family. He canceled traditional celebrations and held weddings in secret. Jeffs outlawed toys and dictated what children were to read. Play is not permitted. When FLDS children were interviewed by Oprah Winfrey in Eldorado in 2009, they told her that they got enjoyment from work, not play.

“Spiritually” marrying girls at a young age is nothing new in the FLDS, but former members say girls have been wed at increasingly younger ages under Jeffs’ rule. Critics say he uses the enticement of underage marriage as a reward for men who remain obedient to him. Often, mothers go along with the plan, although some weddings have taken place without either parent knowing the secret ritual was being performed.

Jeffs moves family members around like chess pieces. He decides who gets married to whom. Men who displease him are sent away to “repent from afar,” while their wives and children are given to other men. The same thing can happen to women who don’t obey. According to Lorin Holm, a man who claimed to have been part of Jeffs’ “inner circle” before he was excommunicated last year, women living in Eldorado were sent away to “houses of hiding” for failing to perform a particular salacious ritual. As Holm described it, the “law of Sarah” is akin to a lesbian sex show with Jeffs participating and sermonizing. Holm said before the Eldorado raid took place, mothers who would not take part in the ritual were sent away to “redeem themselves,” after which their children were given to other women.

A Win for the FLDS

By April 25, 2008, the hundreds of children the state removed from the ranch had been placed in various foster care facilities. To educate its employees about the group, the Department of Family and Protective Services organized a crash course on all things FLDS. It brought in former members to talk about the group’s customs and beliefs. Foster care providers were given a description of what children in the group are taught, what they wear and what they eat. Copies of the Book of Mormon were made available to foster care facilities.

Then, one month later, the department received a devastating legal blow. The FLDS had appealed Judge Walther’s decision to allow the state to take temporary custody of the children, and on May 22 Texas’ 3rd Court of Appeals ruled that the agency had not shown evidence sufficient to justify an “emergency” removal of all the children. According to the Texas Family Code, simply showing evidence of abuse is not enough to warrant such a removal. The agency needed to prove that there was “a danger to the physical health or safety of the child,” an “urgent need for protection,” and “a substantial risk of a continuing danger if the child is returned home.” On May 29, the Texas Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s ruling, although a dissenting opinion stated that the agency was correct to remove the teenage girls from the ranch. Of all the setbacks state officials had encountered—the fictitious “Sarah,” the deceitful mothers and the negative publicity—the appellate courts’ rulings constituted a near-knockout punch. The children would have to go home.

On June 2, a reluctant Judge Walther did as the 3rd Court of Appeals directed her, vacating her order that had placed the children in state custody. The order to return children to the ranch came with some restrictions. For instance, the parents would have to stay close to the ranch and cooperate with the ongoing investigation. Hours later, FLDS spokesperson Willie Jessop released a prepared statement that seemed to come out of nowhere: “The church commits it will not preside over the marriage of any woman under the age of legal consent in the jurisdiction in which the marriage takes place.”

After Judge Walther signed her order, both Willie Jessop and state officials expressed satisfaction, leaving some to suspect that the FLDS proclamation and the parental restrictions had been part of a deal struck between sect lawyers and the Department of Family and Protective Services. Among the people who were dismayed by the news that the children would be returned to the ranch were former members of the FLDS. Carolyn Jessop, who had testified at the hearing about her husband’s abusive behavior, said she was “heartbroken” to learn that the children would be released from state custody. Jessop told the Voice of Deseret blog, “I am sure [FLDS members] believe they are invincible, that they have prayed and fasted … and that God has answered their prayers.”

Nonsuiting Cases

Even as the children were allowed to go back home, the investigation was far from over. The children’s cases were still officially open. The results of the DNA tests that Judge Walther had ordered would soon be in and could prove that men had violated the law by having sex with underage girls. State officials could have handled the cases in a number of different ways, from closing cases in which they found insufficient evidence of abuse to seeking termination of parental rights and making children available for adoption.

The first order of business, however, was for the Department of Family and Protective Services to get its house in order. Two months after the Texas Supreme Court issued its ruling, the agency hired an attorney from Austin to help it sort through the massive amount of documentation it had accumulated since the raid. Charles Childress not only had a long career in family law, he had helped write the Texas Family Code. It seemed as though the agency had found the right person to comb through the evidence and determine which cases would stand up in court and which ones should be closed, or “nonsuited.”

Childress could see right away that a number of cases needed no more court oversight and should be nonsuited. For example, 26 of the “child victims” were actually adults. Childress moved to nonsuit those cases first.

But in some cases, state officials had clear evidence of abuse and neglect. DNA evidence and interviews with FLDS girls showed that parents had offered up their underage daughters to be “spiritually married,” and men had entered into such marriages with girls under 17. In fact, the day before Childress assumed his post, a Texas grand jury indicted Warren Jeffs and five other FLDS men for child sexual abuse and other crimes. Childress said in an interview he felt he had “graphic proof” that some FLDS men had participated in what amounted to “a sex abuse ring” with minors.

Jeffs’ own dictations from November 25, 2003, reveal his efforts to indoctrinate boys and girls in the practice of underage marriage: “I will teach the young people that there is no such thing as an underage Priesthood marriage, but that it is a protection for them if they will look at it right and seek unto the Lord for a testimony. The Lord will have me do this, get more young girls married, not only as a test to the parents, but also to test this people to see if they will give the Prophet up.”

After examining the evidence, Childress felt there were three to five cases, involving 20 or 30 children, in which there was sufficient evidence of abuse or neglect for the agency to go to trial and make the case that the parents should lose their custodial rights. Childress wanted to go after the organization’s “ringleaders,” as he put it, including Warren Jeffs, his right-hand men and some of their wives.

“I felt that we could make a case that the children could be placed with mainstream Mormons and raised with a much better chance at a reasonable life,” Childress later wrote in an email to the Observer.

But his plan was derailed, surprisingly, not by FLDS attorneys but by his own client. Childress learned that when state attorneys filed the original petition in Judge Walther’s court, they left out language that would have allowed the agency to terminate parents’ custodial rights. Typically, termination is considered a last resort—caseworkers always first try to reunite families—yet filing for termination is still standard practice when children are removed from the home in abuse cases. The department had the ability to amend the petition later, but that would have required that every family be personally served papers notifying them of the change, and the agency didn’t have the resources to do that. (To this day, Childress says, he has “no clue” why state attorneys didn’t include termination language in the original petition.)

With termination not an option, at least for the moment, Childress continued to “clear the decks” by nonsuiting cases in which “parents were apparently cooperative and protective.” Some of those cases may have included parents who allowed their underage daughters to be “spiritually” wed, but the proof was thin. Plus, Childress said, all parents would work with caseworkers to develop agreements called safety plans, under which parents would commit to prescribed steps—sometimes including psychotherapy—to ensure that their children are raised in a healthy and safe environment.

Yet many families resisted signing safety plans, which to some child advocates meant they would not provide a safe home and should be denied custody. In August 2008, the state sought to take temporary custody of eight children whose parents were uncooperative. In filing its motion, the state presented evidence that the families in question were unlikely to follow the law in regard to the sexual abuse of minors. According to an affidavit, an FLDS wife told a caseworker that marrying girls who are below 18 “can’t be a crime, because heavenly father is the one that tells Warren when a girl is ready to be married.”

Another affidavit cites a letter written by a 14-year-old girl to Warren Jeffs, to whom she was to be “spiritually” married. “I want to be ready when your arms welcome me to your warm embrace and our kiss be long and sweet!” the girl writes. The letter is signed, “Your wife Eternally.”

Faced with these kinds of cases, Childress knew that the original petition filed in Walther’s court was not sufficient. As things stood then, if he were to take the worst cases to court, the most he could fight for was to put the children in foster care until they turned 18. It was an option Childress strongly opposed for both legal and ethical reasons. He much preferred adoption. So Childress told agency officials that he planned to amend the original petition to allow for the state to claim custody of the abused children and have them adopted. But in a meeting with state officials, Childress was flabbergasted by their unsupportive response. “I was asked several times if I could guarantee a ‘win.’ And I said, ‘Well, I can’t imagine any Texas jury sending these kids back to Warren Jeffs and his wife, but I can’t guarantee it.’”

The conversation degenerated further, Childress said, as one state official wondered “whether I could prove it was in the best interest of the children to be suddenly removed from the only people they had ever known as caretakers and parents.” Another asked “why it was abusive to groom boys to take advantage of plural arranged marriages with younger women.”

To Childress, it was starting to feel as though agency officials had made up their minds to not terminate any parents’ custodial rights. Furthermore, Childress felt his agency client had little interest in listening to his advice. “All I was being asked to do was to preside over the gradual collapse of the civil case, while the [attorney general] pursued criminal convictions,” Childress said.

So he quit. By that time, the department had nonsuited the cases of about 400 children. Cases involving dozens of children remained in limbo. Following Childress’ departure, an on-staff attorney who had been working with Childress on the case took over as chief counsel. That attorney, Jeff Schmidt, lasted only one day in that position, running into the same problem that had stymied Childress. Like his predecessor, Schmidt said he felt the agency had “solid evidence” that would allow it to satisfy state requirements for terminating the parental rights of Warren Jeffs and other parents who had committed egregious abuses. But when Schmidt recommended that the department seek to terminate, he was taken off the FLDS case.

Childress and Schmidt weren’t the only employees concerned about some FLDS children being left with their parents. In one case, the agency filed in court a “petitioner’s determination of expert witnesses,” which contained the viewpoints of 13 Child Protective Services caseworkers, investigators and contracted therapists concerning 10 children of Warren Jeffs and one of his wives. The experts concluded that it was in the best interest of all 10 children that the state obtain “permanent managing conservatorship” of the children. Yet rather than terminate the parental rights of Jeffs and the wife in question, state officials nonsuited that case, too.

Some attorneys ad litem, who were appointed to represent the children, strongly opposed the agency’s actions. The way they saw it, the agency was forcing abused children to continue living under the care of their perpetrators. Natalie Malonis of Dallas, who represented a number of the children, noted that once a case is nonsuited, court oversight goes away. The agency can no longer monitor a child. “It’s like the case never happened,” Malonis wrote in an email to the Observer.

Malonis was particularly concerned about how the agency was handling one of her cases that involved a 16-year-old daughter of Warren Jeffs. Malonis said she begged state officials to hold off nonsuiting the case, as she was close to getting the girl a portion of the church’s enormous trust fund. Malonis hoped that those resources would allow her client to “have some choice” in life. For instance, Malonis thought, the girl might one day want to leave the sect and pursue an education. But Malonis said the state “just flat out resisted me” and nonsuited the case. “That kind of thing happened more and more toward the end, to the point where they were nonsuiting without even checking with ad litems. They were not interested in what was going on with these kids or providing them a safe environment.”

The Department of Family and Protective Services released its final report on the investigation on December 22, 2008, less than eight months after authorities raided the sect’s refuge. The agency stated that, of the 439 children taken into custody, 12 girls were found to have been sexually abused as part of “spiritual” marriages. Those 12 were also victims of neglectful supervision, since those responsible for them had failed to protect them from abuse. In addition, 263 children who were exposed to the custom of underage “spiritual” marriage were victims of neglectful supervision. The agency also tallied up the perpetrators: 30 adults were deemed to have sexually abused girls; 94 were considered perpetrators of neglectful supervision.

By the time the report was published, the agency had nonsuited the custody cases of all but 15 children, and it didn’t take long for the agency to nonsuit the rest, save for one case that involved a 15-year-old girl. Her case would not be resolved until the next summer, when she was sent to live with an aunt who had recently moved from Utah to San Antonio.

The girl would later be one of two victims in the criminal trial against Warren Jeffs. Prosecutors showed that Jeffs had “spiritually” married the girl when she was 12. The jury listened to an audio recording of Jeffs raping her in the temple as two women “assisted” by tying his hands to hers. The aunt would act as a parent, making day-to-day decisions for the girl, and a court order prevented the girl from making contact with Jeffs. However, the girl’s parents, who had overseen the union between the girl and Jeffs, retained custody. It also rankled critics that the aunt, an FLDS member, had been deemed a “safe placement option” by the state because she had never lived on the Yearning for Zion ranch and some of her grown children had left the sect.

Putting Politics over Protection?

One year after the raid, the Texas House Human Services Committee held a hearing to review what lessons could be learned from the investigation. In questioning Department of Family and Protective Services Commissioner Anne Heiligenstein, state Rep. Drew Darby pointed out the investigation’s high price tag and seemingly paltry results and insinuated that politics was at play when the agency nonsuited en masse.

“We spent $12.5 million, and for what?” Darby asked. “Did we just lose our will? Did someone put pressure to pull up short?”

Heiligenstein was unmoved, stating that the investigation “was worth it,” because it served to protect FLDS girls from underage marriage in the future. “That investigation has assured that many, many more children will not suffer abuse,” she said. “The FLDS have acknowledged our concerns and the children are now safe in their homes.”

Pressed by Darby to explain why the agency did not follow the recommendations of Childress and Schmidt to terminate some FLDS parents’ custodial rights, Heiligenstein answered coolly, “They are the attorneys, and their client did not agree that terminating the parental rights was in the best interests of the children.”

The agency has never publicly stated why it had not allowed for termination as an option in the original petition nor why it nonsuited all but one case. When asked about this, Department of Family and Protective Services spokesperson Patrick Crimmins denied that the agency had made an across-the-board decision not to seek termination of parental rights. He said the agency makes decisions about where children should end up “on a case-by-case basis after considering all of the evidence.” Asked about the department’s decision not to seek termination of parental rights in the handful of winnowed cases—cases Childress and Schmidt found to offer overwhelming evidence of child sexual abuse—Crimmins responded that it came down to recommendations by Child Protective Services (CPS) officials, who did not push for termination. “At no time in the course of the FLDS legal suits did CPS recommend termination of parental rights because the staff in CPS vested with the authority to make that decision did not believe that termination was the appropriate course of action.” Asked why those individual staffers found termination to be inappropriate, Crimmins said he could not answer that question “without revealing attorney-client privileged information.”

Critics, on the other hand, say the agency’s decision to nonsuit all but one of the cases is suspect, that it buckled under pressure from the FLDS and its attorneys, the media, and the public—an accusation the agency denies. Independent investigator Sam Brower, who communicated with agency officials about the sect during the investigation, said the agency was largely reacting to fear of being sued by the FLDS, that the initial letter written to Cary Cockerell by FLDS lawyer Rod Parker had “CPS’ knickers in a knot.” Attorney ad litem Natalie Malonis said the agency “literally wanted to get rid of these cases” and avoid lengthy, expensive trials. “They did not want more evidence of abuse to be uncovered, because it would have been more difficult then to nonsuit,” she said. “Such an enormous opportunity to make a profound difference in the lives of so many kids, and it was thrown away for political reasons. There will never be another opportunity of that magnitude.”

Randy Mankin, publisher and editor of The Eldorado Success newspaper, said that while Child Protective Services caseworkers did an outstanding job, the agency failed “at its highest levels.”

Mankin said state officials simply wanted to “get away” from the case. “They started stiff-arming this thing and pushing it away when the 3rd Court of Appeals issued its ruling.”

One woman who wants to go by the name “Jane” was a Child Protective Services caseworker during the investigation. She requested anonymity because caseworkers aren’t supposed to speak with reporters. Jane believes politics took precedence over child safety. “The state was so extremely concerned with the media that they just did not even fight for any additional cases. They were more concerned about covering their own ass,” she said. Instead, Jane said, the agency should have fought to terminate some parents’ rights, even though the appellate courts had not ruled in its favor. “OK, your tail’s between your legs. It’s time to say, ‘We know we did wrong. Let’s suck it up, and in the cases where we really have concerns, re-file.’ Re-work the case, you know? Re-work a frickin’ case! That’s what we do. That’s what our job is, to protect kids, and they didn’t do that.”

Did the Agency Break the Law?

There was no question the FLDS case was highly unusual, yet critics argue that state officials unnecessarily ventured well beyond standard protocol. Examples include the department’s decision to allow FLDS mothers to accompany the children removed from the FLDS ranch, and the massive nonsuiting of cases. Jane, the caseworker, said the agency was obsessed with controlling information in the case, which led to a level of micromanaging that made it difficult for her to do her job.

But at one point, agency officials may even have violated the law. The incident concerned the case of a teenage FLDS girl who had a baby. According to Sam Brower, the Texas Rangers wanted to test the infant’s DNA to identify the father. As Brower writes in his book Prophet’s Prey, the officers were frustrated because the girl had already failed to produce the baby in court for DNA testing. So when the Rangers found out Child Protective Services had arranged a meeting with the girl, they asked the agency to tell them where the meeting would take place.

According to Brower, the agency refused to reveal that information. One source, who was close to the investigation and did not want to be named, said the Attorney General’s office presented the case of the uncooperative girl before a grand jury, alleging that she was hindering the investigation. During the proceedings, the grand jury began asking prosecutors about the possibility of issuing an indictment against Child Protective Services for refusing to reveal the whereabouts of the meeting with the girl. When the agency learned it might be named in a criminal case for hindering an investigation, it backed off and gave the Rangers the information they needed and the matter was dropped.

Asked about the incident, Crimmins wrote in an email that he would not comment, calling the incident “case-specific.”

More Evidence of Abuse

The state’s final report on the investigation focused only on child sexual abuse that stemmed from the practice of underage “spiritual” marriages. But as early as April 2008, caseworkers and attorneys who spent time with the children and reviewed their case files also saw signs of possible sexual abuse that did not relate to underage marriage. Just a few weeks after the raid, the Department of Family and Protective Services issued a memo detailing “preliminary investigation findings,” which stated, “A few interviews with young boys resulted in outcries of sexual abuse. Follow up forensic interviews at the children’s advocacy center resulted in an outcry of sexual abuse against older boys in one case. Another forensic interview of a young boy making an outcry was tainted after his mother coached him not to reveal information to investigators. Evidence in the form of a journal taken from the Yearning for Zion Ranch supports the possibility of sexual abuse of boys.”

Caseworkers and others who observed the children in foster care noticed worrisome behaviors—behaviors that experts say can be signs of ongoing sexual abuse. For example, one foster care provider said she saw young girls trying to vaginally penetrate themselves with objects. Another caregiver at a different facility that took in 12 children said 10 of them wet the bed every night, and two boys well past diaper age occasionally defecated on themselves.

One attorney ad litem filed a report in court stating her concerns that a 2 year old had been sexually assaulted and requesting that the child be checked for possible sexual abuse “to include the anal area.” A document filed by Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) of Tom Green County noted that the child “sometimes has fits of temper” and didn’t play with other children. During a visit by the boy’s mother, the CASA worker noted “a definite distance between [the boy] and his mother. He didn’t seem to care that his mother was there and she paid more attention to his brother. She spent a lot of time hugging/cuddling [the brother] and no hugs for [the boy in question].”

The individuals who observed signs of possible abuse were required by law to report what they saw. In fact, most told the Observer they reported their observations to Child Protective Services. So it remains a mystery why the agency found no allegations to be valid. When asked about this, Crimmins wrote in an email that evidence of sexual abuse came from documentation of underage “spiritual marriages” and DNA evidence. “There were no outcries of sexual abuse made by any child or parent during the course of the investigation.” He added, “We did not obtain any other evidence that supported [a reason to believe] finding of other abuse allegations.” Further, Crimmins wrote, “All allegations and evidence for each individual case were thoroughly reviewed to ensure the accuracy of each finding, based on the information that was available.”

Still, critics doubt that the agency was diligent about pursuing evidence of abuse and neglect. “It’s not that CPS wasn’t aware of the concerns,” said Natalie Malonis. “They just didn’t do anything about it or didn’t follow up.”

‘We Changed the Culture’

In announcing the closure of the final case—that of the 15-year-old girl who went to live with an aunt—Department of Family and Protective Services Commissioner Anne Heiligenstein stated in a press release, “We believe all of these children are safer because of our intervention.” It was a talking point agency officials frequently repeated. One year after the raid, spokesperson Stephanie Goodman told the Houston Chronicle, “I cannot help but believe that we changed the culture there.”

But many find the idea that the state agency could have had such a profound impact on the FLDS ridiculous. Some people questioned on this point simply laughed.

“I don’t believe it for a second,” said Joseph Broadbent, the young man who fled the FLDS when he was a teenager. If Jeffs wanted his followers to break the law, they would do it, unquestioningly, Broadbent said. “Nothing will stand in Warren’s way. That’s the way he is. He believes he’s almost Jesus, and no one can stop him.” He added that Jeffs might now be even more powerful than he was before the raid occurred. “He’s got hours and hours to sit around and think about what he’s going to do next.”

In fact, since going to prison on a life sentence, Jeffs has maintained control of the sect, sermonizing through letters and phone calls from his cell in Palestine, Texas. Jeffs has ordered families to pay $5,000 to the church and to get rid of toys, bicycles and trampolines. The sect leader has required married couples to get his approval to have sex and recently decided that only 15 men in the group could serve as fathers to all the children. Nadine Hansen, an attorney in Cedar City, Utah, said that as of May 15, 2012, Jeffs had stopped all underage marriages, but that any day he could tell his “lieutenants” to order members to resume the practice. “All it takes is one phone call,” Hansen said.

Attorney Jeff Schmidt puts little stock in the parental agreements signed by the sect’s parents. He pointed out how, in the FLDS, “It’s acceptable to lie to ‘gentiles.’”

Others see the agency’s claim as disingenuous. Private investigator Sam Brower said claiming to have changed FLDS culture was a way to “justify their bailout. It’s such an obvious way to try and save face.” Given that the FLDS is generations old, Brower said, “I can’t even find the words to describe how ignorant that notion is.”

The sad truth is that few outside the sect know whether the culture actually has changed. After the investigation was over, some caseworkers and foster caregivers remained in contact with some mothers, but that lasted for only a short while. Former FLDS members who used to track the children now say many seem to have disappeared. When the children returned to the ranch after the Texas Supreme Court decision, Warren Jeffs had the families scatter to other “places of refuge.”

Was It Worth It?

Looking back, the custody case that involved more than 400 children and made international headlines generated mixed results. On the positive side, FLDS children were exposed to the outside world for the first time and thereby came to realize that “gentiles” are not necessarily the evil, misguided people they had been taught to believe. Boys and girls could do things they hadn’t previously been allowed to do, such as play with toys and read books of their own choosing. “We tried to give them a sense of fun,” said a woman who ran a foster group home and did not want to be identified. She said the children loved riding bikes that had been donated, and that one day they got to play on a waterslide. The girls slid down the slide in their dresses, she said, despite the fact that the children had been taught that pools of water contain “demons.” “They had a blast,” she said.

Interactions between caseworkers and children were intensely strained in the beginning, but many ended up bonding. Sharon Berger was working for Child Protective Services as a substance-abuse expert when the raid took place. She was deployed to the San Angelo Coliseum as a manager and also observed some of the children going back to their parents. “It was really interesting for me to have seen the conflict between the mothers and CPS and how much they absolutely despised us at the coliseum, and then a month later to see them hugging their caseworkers, talking to them as if they had divulged everything to them,” Berger said.

The investigation also highlighted weaknesses in the child protective system. As a result, the Texas Legislature passed laws that toughened penalties for crimes of child sexual abuse and bigamy, and imposed new regulations on how caseworkers do their jobs. For instance, they now must first act to remove suspected perpetrators from a home, rather than victims, and if children must be removed, adults may not accompany them.

According to the state, 170 cooperating FLDS mothers and fathers took parenting classes and 50 girls participated in “therapeutic education” in which they learned about sexual abuse. Caseworkers arranged to provide services, such as counseling, to certain families.

“We poured all of our resources into this investigation, and hope that we made a difference in this particular community,” wrote spokesperson Crimmins in an email. “We were able to confirm for the first time that sanctioned sexual abuse of children was occurring, and had been for some time. We worked very hard to help parents and children in the community understand what abuse is, and how it can and should be reported. Legally, we did all we could, consistent with the best interests of the children, to ensure that the children who were returned to their parents or caretakers were going to be safe.”

Still, many wonder what the investigation actually achieved. While the agency boasts that families were presented with safety plans, only 29 of 146 families actually signed them. What’s more, as a result of agency officials nonsuiting almost all the cases and not seeking to terminate the custodial rights of parents, all 11 men currently serving prison terms for sexually abusing underage girls maintain custody of their children. (A criminal conviction does not automatically terminate parental rights.) The same is true of mothers who enabled the abuse. (So far no women have been prosecuted.)

“Warren Jeffs, to this day, has all the rights and duties of any other parent, including the right to direct their education and upbringing, designate where his children will live, and consent to marriage, among other things,” Charles Childress said.

The investigation took a toll on just about everyone involved. FLDS parents were thrust into a legal system they did not understand. And because siblings in foster care were not always housed together, some parents had to drive long distances to visit their children. Children were taken from the only community they had ever known. One caseworker’s notes from the San Angelo Coliseum reveal how distressed one little girl was when a state investigator sought to interview her. The girl “continued to bury her head into her mother’s stomach and cry,” wrote the caseworker, adding that further attempts to interview the girl were “emotionally traumatizing.” Attorneys ad litem who worried about the safety of their child charges saw them returned to sect members. Some of those members were not the children’s parents—the adults picking up the children only had to show documentation that they had the parents’ approval. There were reports of caseworkers pushing crying children across the room to the adults picking them up.

Child Protective Services caseworkers had a particularly hard time, especially those who worked at the coliseum. “We were at the top of our adrenaline constantly,” said Sharon Berger, who later sought therapy and believes she was left with a mild version of post-traumatic stress disorder. FLDS children, who are taught to look down on African-Americans, hurled brutal insults at caseworkers with dark skin. Berger, who is white, recalled a 4-year-old boy calling her “wicked” and “evil” because she had short, red hair. She was alarmed to see the sect’s patriarchal social structure manifest itself, even among the youngest members. “These 3- and 4-year-old little boys told their moms what to do. And the moms did it. All the women did it. All the girls. They all did what these toddler boys told them to do.”

Jane, the caseworker, said she, too, suffered with PTSD from her time working at the coliseum. It took a year before she could talk about what happened on the last day, when the children were separated from their mothers and sent to foster care facilities. When the announcement was made, Jane said, there was “screaming, crying, mass panic.” Jane collapsed from the emotional strain and exhaustion, and she was not the only one. “CPS workers were dropping like flies,” she said.

It is possible that Child Protective Services could once again investigate the FLDS, but that seems unlikely. With the final child’s case closed in July 2009, Judge Walther dismissed the agency as a “party of interest,” which officially ended its role in the investigation. Even if the agency were willing to risk again being pilloried by the media and the public, it would have to receive a report of abuse from an “outcry victim” before opening a new investigation.

“There are no complaining victims,” Willie Jessop told the San Angelo Standard-Times last year. Once devoted to Jeffs, Jessop is now part of a breakaway FLDS sect under the direction of another “prophet.” Jessop said girls in the sect under Warren Jeffs’ control “are trained to be so obedient. They’re indoctrinated beyond anything I’ve seen before the [Yearning From Zion].”

Now that Child Protective Services is off the case, Sharon Berger worries that abuse victims will shut down. She said when the state first gets involved in a case, it’s not uncommon for children to talk about having been abused and express a need for protection. But, Berger said, “If we fail them in their eyes and go back the next time, they will get quieter and quieter, while the family learns how to abuse more secretly.”

“I think [state officials] really messed up in a lot of ways,” Jane said. “I think they gave undue trauma to children who were not victims of abuse and neglect. I think they traumatized families of the FLDS that were not engaging in abusive and neglectful behaviors. And then I think that they were not responsible in terms of how they treated the cases where there was abuse and neglect.”

Although many FLDS members who had been living at the Yearning for Zion ranch have been moved to other “places of refuge,” there is still much activity at the compound. A former member said there were plans to bring down from Utah a group of girls, ages 12 to 17, to do chores at the ranch to “improve themselves,” and that the compound had become a “training ground of sorts.”

Meanwhile, locals in Eldorado have been talking about a new construction project underway at the ranch. The FLDS has been building a concrete stadium as wide as a football field, and in the middle, members plan to erect a 30-foot statue of Warren Jeffs. According to a sketch of the statue, the “prophet” will be portrayed holding a religious text in one hand and, in the other, the hand of a little girl.

Janet Heimlich is an independent journalist and the author of Breaking Their Will: Shedding Light on Religious Child Maltreatment.