The ‘Antifa Scare’ Goes on Trial in North Texas

As nine of the "Prairieland 19" face their days in court, the broader constitutional rights of left-wing activists may hang in the balance.

On a warm Saturday afternoon in February, a small group of 10 people walked through a metal gate, propped open with a black trash can, and into a beige, fluorescent-lit room inside a teachers union hall in the Oak Cliff neighborhood in southern Dallas. They were there for a presentation titled “The Prairieland Defendants: A Landmark Battle for Free Expression & Immigrant Rights.”

“We’re going to do a little poll,” said Ramón, who requested that the Texas Observer use only his first name for fear of reprisal and is a member of the DFW Support Committee, a group working to support the Prairieland defendants. “If you’ve ever been to a protest, raise your hand,” he said. “Raise your hand if you have ever worn all black, in general, not even at a protest. Raise your hand if you have a first aid kit. If you own a gun, raise your hand. If you’ve ever used Signal, raise your hand.”

With each question, hands were raised. “If you raised your hand, does that make you a terrorist?” asked Luis, another DFW Support Committee member who made the same request for partial anonymity. “That’s basically what the state is trying to do with our friends.”

Ramón and Luis are part of a group composed of family and friends of the defendants in a controversial federal criminal case alleging that a dozen protesters—who took part in a July 4, 2025, protest outside the Prairieland Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center in Alvarado during which one protester allegedly shot a police officer—and seven others are members of an organized “North Texas antifa terror cell,” as described in federal complaints and press releases.

In federal court filings, federal prosecutors have cited the protesters’ all-black “military style” clothing, the zines and flyers they possessed, their use of the encrypted messaging app Signal, their possession of first aid kits and Faraday bags (used to prevent wireless tracking of phones), and their discussion of whether to bring firearms in order to argue that they were part of a criminal conspiracy to commit terrorist acts.

The case is the first time the government has ever filed terrorism charges against “antifa”—short for “anti-fascist,” a decentralized ideological movement—and a federal jury trial that began February 17 is the first major test of the Trump administration’s campaign to label left-wing activists as domestic terrorists. It has raised alarm among legal experts because of the logic that prosecutors have used to argue that the defendants, including several who didn’t even attend the protest, are a part of an organized criminal enterprise.

Defendants, their attorneys, and supporters say they only intended to protest Trump’s immigration policies last July and emphasize that protesters have said they didn’t plan on committing violence, while some defense attorneys have singled out one defendant as allegedly having a separate agenda. Supporters also argue that the defendants are being politically persecuted for their ideological beliefs. Several members of the “Prairieland 19” have been linked to the anti-fascist Elm Fork John Brown Gun Club, the Socialist Rifle Association, and an anarchist reading group that distributes zines.

Nineteen people in total have been arrested and face a mix of federal and state charges. Prosecutors argue they engaged in a conspiracy to commit acts of terrorism and accuse them of a range of activities, such as attending the demonstration, helping plan it, or interfering with the investigation. Nine of the defendants have pleaded not guilty and are now facing trial on charges including attempted murder in one case. In November, seven defendants, including four who weren’t even at the protest, pleaded guilty to federal charges of providing material support to terrorism or damaging property. Three others who were arrested months after the protest, which they did not attend, have yet to plead or go to trial. Nearly all of the defendants still in custody are under million-dollar bonds. Several have been held in solitary segregation cells.

On July 4 last year, about a dozen people gathered outside the Prairieland ICE detention facility for a noise-demonstration—a style of disruptive protest where participants create loud noises, in this case using fireworks—during which a confrontation resulted in a protester and law enforcement engaging in a shootout that left one officer injured. Federal officials were swift to describe what happened at the protest as an “ambush” and “planned attack.” But prior reporting in other outlets has shown the facts of the case are murkier than what is conveyed in government press releases.

In comments to The Guardian and The New Republic, Xavier de Janon, the director of mass defense at the National Lawyers Guild, has argued that this case could shape “the future of American civil liberties” and set a precedent that results in “people facing terrorism charges for doing very simple mainstream activism.”

The White House has broadly defined antifa as a threat and has cited the Prairieland case as part of a wave of purported anti-fascist terrorism. In September, President Donald Trump signed an executive order labeling “antifa” a domestic terrorist group, a designation that doesn’t exist in federal law. That same month, Trump issued National Security Presidential Memorandum-7, which cited the Prairieland case and the assassination of Charlie Kirk as evidence of organized political violence from the left.

In Texas, Attorney General Ken Paxton followed Trump’s lead, publicly announcing the launch of “undercover operations to infiltrate and uproot leftist terror cells” in October, citing the Prairieland shooting and an unrelated shooting at the Dallas ICE field office. Last month, Paxton opened a probe into a Houston anti-fascist group, the Screwston Anti-Fascist Committee, accusing the group of potentially violating state law by aiding in the commission of terrorism and “doxing” and alleging that “affiliates” of the group participated in the Prairieland protest. Screwston, which was formed in 2016, has identified a number of neo-Nazis in the Houston area, sells merchandise with messages like “Antifa Zone,” and has worked with the DFW Support Committee to help raise funds for legal fees to support the Prairieland defendants. None of the Prairieland defendants are from the Houston area, and there is no evidence linking members of Screwston to the protest.

Tom Brzozowski, former counsel for domestic terrorism at the Department of Justice, told KERA that the administration’s broad definition of “antifa” and its demonstrated focus on prosecuting related beliefs worries him. “That’s incredibly dangerous,” Brzozowski said. “It introduces a degree of ambiguity that is going to result in Americans choosing to not exercise their constitutional rights for fear of being swept up in some kind of dragnet.”

What’s known of what exactly happened at Prairieland, based on case filings and The New Republic’s review of camera footage, is as follows.

On July 4, 2025, 11 black-clad protesters approached the Prairieland Detention Center. Two protesters spraypainted “Fuck You Pigs” on a structure and “ICE Pig” on a car in the parking lot, triggering federal officers to call the local police at around 10:56 p.m., roughly fifteen minutes after the protesters had begun shooting fireworks toward the facility’s razor-wire perimeter. Two officers exited the building to confront the protesters at 10:58 p.m., and, a minute later, Thomas Gross, an Alvarado police lieutenant, arrived at the scene and demanded the scattering protesters halt and get on the ground.

Prosecutors attest that a protester yelled “Get to the rifles!” Then, someone fired shots, the two federal officers ducked for cover, and a bullet hit Gross, entering above his collarbone and exiting his upper back. Gross shot back, firing three rounds. When an Alvarado fire marshal arrived shortly after, Gross told him which way the protesters had fled, and the marshal drove Gross to a nearby parking lot to be taken to the hospital in an emergency helicopter. Gross was released from the hospital within 24 hours.

The original July 7 federal complaint alleged there had been multiple shooters and asserted 20 to 30 rounds were fired, but later filings reduced the number of alleged shooters to one and the number of rounds fired to 11. In a lengthy preliminary hearing in September, an FBI official told the court that he could not say for certain who shot first.

Ahead of the protest, members of a Signal group chat discussed whether they should bring guns. Benjamin Song, a former Marine reservist and the alleged shooter, argued firearms would deter an escalation if a confrontation with police occurred. “Cops are not trained or equipped for more than one rifle,” he allegedly wrote, “so it tends to make them back off.” Police recovered 11 firearms from the arrested protesters, many of them inside cars or unassembled in backpacks. Multiple belonged to Song. Prior to his arrest, Song was affiliated with the Elm Fork John Brown Gun Club, whose black-clad members have routinely carried long guns at protests across North Texas over the last few years without violence, including during a standoff with Dallas authorities that delayed the clearing of a homeless encampment in July 2022 and did not result in any arrests.

In recent years, both left- and right-wing protesters have toted guns at protests, and Governor Greg Abbott himself has said, “There are protests and other activities that occur all the time when people are carrying guns and doing so lawfully.”

The night of the shooting, police arrested eight of the 11 protesters: Elizabeth Soto, Ines Soto, Nathan Baumann, Maricela Rueda, Seth Sikes, Savannah Batten, Zacharry Evetts, and Joy Gibson, Song’s girlfriend. Meagan Morris, who didn’t actively participate in the noise-demonstration, was pulled over near the scene and arrested. Morris, a transgender woman, told KERA News she was parked half a mile away from the ICE facility and hadn’t even gotten out of the car when she heard a gunshot.

Sikes, who has pleaded guilty to providing material support to terrorists, told prosecutors that the role of Song, the alleged shooter, was to use his rifle to intimidate law enforcement so that the protesters could escape. Baumann and Gibson, who also pleaded guilty to providing material support to terrorists, told prosecutors Song’s role was to alert protesters if police arrived.

Another protester, Autumn Hill, also a transgender woman, was arrested the next day in a raid on her home. In the aftermath of Kirk’s death, the Trump administration has crowed about an ostensible rise in “trans violence.” Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said in September that “it’s worth looking into” and that “anyone who denies that at this point is being willfully ignorant.” Both Hill and Morris have been indicted under their names given at birth, despite having legally changed them, and have been held in facilities that do not align with their gender.

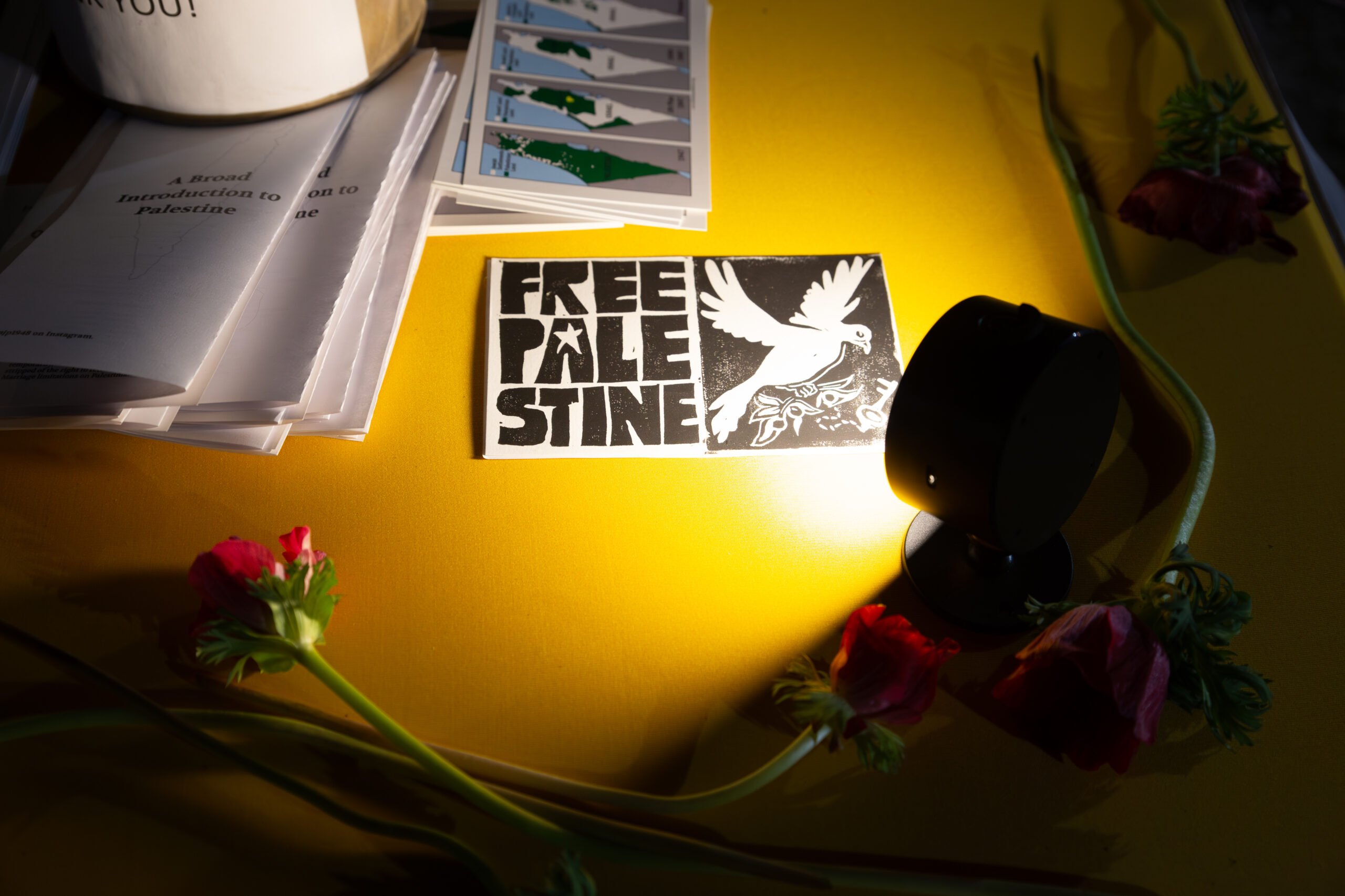

On July 7, Daniel Sanchez Estrada, husband to Rueda, was the 11th person arrested—for removing a box of “antifa materials” including anarchist zines and art from Rueda’s home, an action prosecutors allege was an attempt to conceal evidence that ICE has described as “literal insurrectionist propaganda.”

Song, the alleged shooter, evaded arrest for 11 days, initially hiding in the nearby woods, and was arrested on July 15 at an apartment complex in Dallas. Several defendants are accused of helping him escape and have been federally charged with being accessories after the fact. Song’s roommate, John Thomas, was arrested on July 10 and accused of smuggling Song from Alvarado to Dallas. Lynette Sharp was arrested July 13 and alleged to have helped plan the logistics of Song’s escape and has been charged with hindering prosecution of terrorism among other alleged crimes. Rebecca Morgan was arrested July 15 and is accused of meeting Thomas at a Home Depot in Dallas to pick up Song, who was arrested at Morgan’s apartment. Susan Kent was arrested on August 7 for allegedly meeting at a hotel in Cleburne to plan Song’s exfiltration.

Thomas, Sharp, Morgan, and Kent have all pleaded guilty to providing material support to terrorists and face up to 15 years in prison.

Dario Sanchez, a teacher in Dallas, was arrested on July 15. The arrest followed a visit from Thomas on July 9, after Thomas’ home had been raided and his electronics confiscated. Sanchez and Thomas were both members of the Socialist Rifle Association. Sanchez then reportedly removed Thomas from group chats. Sanchez told The New Republic that an FBI task force officer offered him a deal: allow police to pose as him online and he could avoid 50 years in prison. Sanchez later got out on bond, only to be surveilled and briefly arrested again after he made a Google search about converting a model car into a remote-controlled device.

In October, the Johnson County Sheriff’s Office arrested the 18th defendant, Janette Goering. She has been charged with aiding in the commission of terrorism. Prosecutors cite her participation in Signal group chats and allege she gave Song a Faraday bag.

The 19th and final defendant, Lucy Fowlkes, was arrested in January and charged with two counts of hindering prosecution of terrorism. She is alleged to have helped delete messages and remove people from group chats. Prosecutors allege that the deleted messages contained evidence of planning the incident and planning to help Song evade arrest and “by extension, [to] hinder prosecution of terrorism.”

A Department of Justice press release describes the Prairieland defendants who participated in the protest as having “dressed in ‘black bloc’,” referring to a protest tactic that emerged in the 1980s meant to conceal the identities of protesters from police and political adversaries, with the department arguing that the tactic is designed “to aid and abet those members engaged in illegal acts by making members indistinguishable from one another to law enforcement.”

The Prairieland case isn’t the first time that the federal government has sought to label the use of black bloc as evidence of a criminal conspiracy. In 2017, when a handful of black-clad protesters destroyed property during the anti-fascist and anti-capitalist Disrupt J20 Rally, police detained hundreds of people who were nearby, including journalists, medics, and legal observers. This became one of the largest politically oriented conspiracy cases in American history, including a total of 212 defendants who faced felony riot charges. An FBI agent opined during the case that black bloc tactics involve “coordinated street-level militancy” and may involve participants who “wear protective padding and helmets to aid in planned or anticipated destruction, violence and/or confrontation with law enforcement,” as described in a prosecutor’s filing previewing expert testimony. A jury was not convinced, and remaining charges were dropped. About 20 defendants pleaded guilty, mostly to misdemeanors.

Prosecutors in the Prairieland case also cite seized firearms, body armor, radios, flyers, first aid kits, and faraday bags as evidence of a “militant enterprise” defined as an “antifa terror cell.”

The National Lawyers Guild has likened the Prairieland case to the post-1945 Second Red Scare, the FBI’s persecution of the Civil Rights movement, and the Green Scare of the early 2000s that targeted the radical environmental movement, arguing that a modern “Antifa Scare” is playing out. Federal officials have been quick to use the same “domestic terrorist” label applied to the Prairieland 19 to describe Renee Good and Alex Pretti, two residents of Minneapolis, Minnesota, that federal officers shot and killed during the course of aggressive deportation operations. Since September, when the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) ramped up deportation operations, federal immigration officers have shot at least 13 people.

The way Mike German, a former FBI agent who later worked for the Brennan Center for Justice, sees it, the logic driving the “Antifa Scare” of today goes back decades. “These groups have been targeted as terrorists for a long time,” German told the Observer. “While it wasn’t put in a presidential memorandum, and they didn’t use the word ‘antifa,’ the FBI has used the word ‘anarchist’ just as they [use] antifa: It was a word that encompassed every kind of leftist protest and actually described nothing.”

Members of the DFW Support Committee worry that if defendants are convicted at trial, it will set a precedent for the government to prosecute any left-wing protest movement as terrorism.

“Right now, we’re seeing our rights trampled on around the country,” said Luis, the committee member. “Depending on how this case turns out, some precedents could be set that will haunt us for decades to come.”