Soul on Ice

After September 11, the Man the FBI Forgot

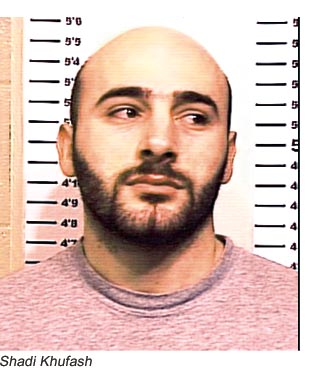

On September 20, Shadi Khufash awoke to a loud and persistent knocking on the door of his two-room Fort Worth apartment. Born and raised in the West Bank city of Nablus, the 26-year-old Palestinian had been in the United States not quite a year and a half when the World Trade Center blew up. He was so fearful of the backlash on the day of the blast that he decided not to show up for his usual graveyard shift at the convenience store where he worked. “Too many cowboys around there,” he said. In the end, it was not cowboys that came for him, but the FBI. “Shadi Khufash, we have some questions we’d like to ask you about September 11,” they told him. He sat on the couch in his pajamas with his live-in girlfriend as three agents, accompanied by an INS officer, searched the apartment.

The agents discovered that Khufash’s visa had expired, and took him to the Dallas County Jail. At his bond hearing, a prosecutor produced a letter from the FBI asking that Khufash be denied bond, and the immigration judge complied. Two and a half weeks later, FBI agents came to the jail and questioned him at length about his knowledge of the attacks. But after Khufash passed a polygraph exam, the FBI announced they were finished with him and the INS promptly ordered him deported. That was in October. Eight months later, Khufash is still in jail in Denton, still being held without bond for a visa overstay, a civil violation that carries no jail time. He does not know why. In the meantime, his girlfriend has left him, Israeli tanks have rolled into his hometown, and his hope of ever getting back home–a place he traveled thousands of miles just to escape–is growing cold.

When Khufash left Israel in May of 2000, there was relative quiet in the West Bank. He was granted a multiple entry visa to the U.S., suggesting he was not considered a threat by anyone. Khufash, perhaps five and a half feet tall, with a shaved head and smiling eyes, did not grow up in a refugee camp, he said in a recent interview in the Denton County Jail. His family was part of the Palestinian middle class, which grew modestly under the relative peace following the Oslo Accords of 1993. His father owned a store, and his uncle a construction business. Shadi and his older brother and sister went to college and learned English. Yet his family by no means escaped the trouble that has plagued the region since before Khufash was born. He was 11 when the first massive Palestinian uprising (intifada) began in 1987. When soldiers began routinely blocking his route to school, he said he reluctantly joined in the rock-throwing. “I did my best to stay away. But sometimes you have to do it. If you don’t, they call you a woman,” he said. One day he found himself in the back of a fleeing group of kids as the soldiers opened fire with rubber bullets. He jumped a wall and landed on his face. Khufash showed me the scars on his lips and the repaired teeth in the front of his mouth. A few years later, he was arrested trying to slip into a Jewish area to look for work. He was shot in the groin with a rubber bullet and held in solitary confinement for days, where he was beaten and interrogated. Worried that he might be injured internally, the soldiers allowed a doctor to examine him, but Khufash was too intimidated to tell the truth about his injuries. “They said if the doctor ask you has someone been beating you, you say ‘no.’ If you say ‘yes,’ we take care of you.” After two weeks, he was released.

When the Palestinian Authority was formed, Khufash took a job with the new police force. It was one of the few good jobs to be had for young Palestinian men–and it was something to be proud of. “For people who never had an almost-government and an almost-army, it was something,” he said. But Khufash didn’t care for the work–chiefly providing security for Palestinian officials and guarding Hamas prisoners. He took an assignment in the kitchen at a base in Nablus.

He came to the U.S. with a group of businessmen on a tour designed to encourage commerce with the U.S. He said he never really intended to go back home. “To be honest with you, I always had a dream to come to the U.S., so when I got here I started to check it out. And the freedom, the democratic, the justice all that, the beautiful country, beautiful people, you know, I would like to stay here. And I can support my family too,” he said. By that time, Khufash’s family had fallen on hard times. His father was sick and was forced to retire. After a few weeks of working at a gas station in Chicago, staying with a cousin and sending money home to his parents, Khufash got in touch with a cousin in Fort Worth who encouraged him to move. (The term “cousin” is used very loosely among Arabs, who can generally expect hospitality from anyone related to them, however distant.)

His cousin owned a tire store, a favorite of Arab immigrant entrepreneurs (low startup costs, good profit margin, Khufash explained). After a brief stint at the store, he began looking for a way to make better money and to stay in the country legally. Recalling that a friend of his from back home had made a good living driving a truck in America, he began lessons at a truck driving academy. “It was not easy for me because of my language, but I finished it. I wanted the money!” he said. Against the advice of his cousin (who warned him to avoid lawyers and doctors in America) he went to see an attorney about applying for political asylum so he could stay in the country. The situation had begun to deteriorate in Israel, and the prospect of open warfare between the Israeli military and the Palestinian security forces was very real. (In February, Israeli forces destroyed the base he once worked on, and several of Khufash’s friends were killed, he said.) Technically, Khufash was still bound to serve in the Authority forces.

Khufash told his lawyer he was afraid of both sides. “If I go to my homeland, I have to help them. If I don’t go back to the security forces, there are too many militia over there and some of them–like Hamas–they are looking for anyone who knows how to use a gun, who used to be an officer, to work with them,” he said. That’s assuming Khufash made it out of the airport. It would not take Israeli intelligence officers long to determine that he was a former Palestinian Authority police officer. “I’m sure they would arrest me at the airport, they would torture me, they would keep me in jail I don’t know how long.”

The lawyer told him if he wanted to stay in the country, he should forget about asylum and marry an American citizen. It was an idea he found appalling. If he wanted to do that, Khufash said, he could have bought into the racket in Chicago, where he was told he could hire a “wife” for immigration purposes for as little as $200 per month. “I said when I marry it will be for my future,” he said. Eventually he did meet an American woman, and after several months of dating they moved in together. After being rejected by a trucking firm for not having a green card, Khufash took the convenience store job. He supported his girlfriend and her two children from a previous marriage by working long hours. He was also sending money home for his younger siblings to go to school.

The roundup that netted Khufash was nothing if not thorough. In the Dallas County jail, he recognized three of his former co-workers from the tire store, two of Middle Eastern origin and one Mexican. (They have all long since been deported.) Khufash doesn’t know how the FBI got his name, but he has his suspicions. Shortly before he was arrested, he quit his job at the store after months of wrangling with his boss, a Lebanese-born U.S. citizen, over his long hours and all-night shifts. Khufash said he thought he left on good terms, although he had yet to collect the last of the money owed him. He now suspects that his old boss gave his name to the authorities out of spite.

Khufash is one of over a thousand Muslim or Arab immigrants detained across the country since last fall. The exact number is an official secret; after the first well-trumpeted round-up of 1,200 suspects, the Justice Department stopped announcing subsequent AR-rests. Most of them apparently have now been deported, but tracking the fate of those, like Khufash, who have not has been extremely difficult. Attorney General John Ashcroft has fiercely resisted efforts to obtain the names of detainees, though most of them are being held in county jails in states where such information is typically public record. (The ACLU has sued for the names in New Jersey, and a similar suit is pending in Washington, D.C.) Shortly after the attacks, Ashcroft ordered that all immigration proceedings be held in secret, with no access by the public or media. An immigrant may have an attorney present, but there is no right to counsel for immigrant detainees, and the overwhelming majority have none.

Although Khufash was fortunate enough to have an attorney, it has not done him much good, partly because of the morass of Middle Eastern politics he came to the U.S. to escape, and partly because of the new security state rapidly being assembled by federal authorities in the wake of September 11. For all intents and purposes, Israel is at war with Arafat’s Palestinian Authority forces. Thus, the chances of Israel, which vigilantly controls the nation’s internal and external borders, voluntarily accepting any Palestinian–much less someone they consider a soldier–back into the country are slim. Khufash again considered applying for asylum, until he met someone in jail who had been waiting more than two years for his asylum case to be heard.

Lucas Guttentag, director of the ACLU’s Immigrant Rights Project, suspects that there may be many more like Khufash quietly sitting in jails around the country. “It’s hard to tell because of the secrecy, but we’ve got reports of people who an immigration judge has ordered deported or who have accepted voluntary departure, but are still sitting in jail because the FBI hasn’t ‘cleared’ them–even though there is no evidence of any involvement with September 11 or any charges filed,” he said. The Supreme Court recently ruled on a case, filed long before September 11, concerning immigrants who cannot be deported because the U.S. has no diplomatic ties with their home countries, such as Cuba. The Court rejected the government’s position that such immigrants could be detained indefinitely (as many Cubans who have committed crimes in the U.S. have been). “The principle in that case is that non-citizens, like citizens, have basic protections under the Constitution and you cannot jail an person arbitrarily,” Guttentag said.

That would seem to be an accurate description of Khufash’s incarceration. Even after the FBI had finished with him, he was inexplicably denied bond by a judge, who called him a “danger to society.” Khufash was moved from jail to jail, eventually landing in Denton. Fearing that his deportation would be indefinitely delayed, in November Khufash agreed to voluntary departure, under which an immigrant buys his own ticket and leaves the country under the supervision of the INS. Chances were good, he knew, that he would probably be jailed and interrogated as soon as he landed in Tel Aviv. “But at least I will be in jail at home, where I can see my family,” he said.

But then came another snag–the INS lost the ID card issued by Israel for residents of the Occupied Territories, without which he would have no chance of reaching home. The Israeli embassy was contacted for a replacement, but they did not respond, Khufash was told. Finally, a breakthrough: In January, the immigration officer handling his deportation told him he would have to be released until his departure could be arranged. He would be on a sort of probation, required to report every month to the INS. Just two weeks, they told him, to finish the paperwork. On January 29, the agency reversed course again. His release had been denied, without explanation. “You can’t imagine what it’s like to be here,” he said, “everyday thinking they will call your name, but they never do.”

According to INS spokesman Lynn Ligon, the long delay has been for Khufash’s own good. The agency has been in protracted diplomatic negotiations, “working night and day,” Ligon said, to get the necessary travel documents to get him home safely. (His ID was not “lost” Ligon said, though it had been placed “somewhere it shouldn’t have been” for a time.) Ligon said that, for security reasons, he could not say exactly by what route Khufash would be traveling home, though he suggested it would involve a third country, and that it would happen “soon.” If the INS is your travel agent, a long wait is perhaps to be expected–but eight months? And why couldn’t Khufash wait in the free world for his departure? No charges had been filed against him, after all. According to Ligon, although Khufash was not considered a criminal alien, the INS and the FBI were concerned about his commercial driver’s license, which theoretically allowed him to haul hazardous chemicals. Ligon did not cite any evidence of illegal activity on the part of Khufash, who never even made it onto the highway during his brief career as an American truck driver.

Khufash has received financial and moral support from a group of friends at the Arlington mosque where he once worshipped. One of them, Badar Almahshri, a 29-year-old cab driver from Oman, said the FBI had been to his house as well. In an interview at a mall coffee shop in Arlington, Badar, who is married to an American, said he and Shadi did not fit any profile that made sense. “People come here to live. If they wanted to fight and kill people, they wouldn’t get married and have kids and have businesses here,” he said. He knew of many in Arlington’s growing Muslim community–there are now three mosques in the blue-collar suburb–who had simply decided to go home.

Khufash himself was reluctant to criticize his captors, but he said that Palestinians had been unfairly labeled terrorists. “Give us a chance. We are building our own government. Give us a chance to stop the terrorists,” he said. He was like most Palestinians, he said, caught up in a conflict beyond his control. September 11–couched by bin Laden in part as a blow against U.S. support for Israel–was just the latest turn. “The Palestinian people get tired sometimes from some Arab people or Arab terrorists using us as a commercial for terrorism: ‘I come to revenge the Palestinian people.’ No, you don’t revenge, you destroy us more!” he said.

“Terrorism never changes anything,” he said. “The only solution is by talk: Convince me, I convince you. If I get in a fight, you kill my son, I kill your son, you kill my wife, I kill your wife–when are we going to stop? But if we sit down, we talk, someday–it may take long–but someday we are going to find a solution,” he said.

Despite what has happened, Khufash said he still hopes to live in the United States someday. “I still love this country, no matter what,” he said. “Don’t forget Bush was the first American President to say we will make a Palestinian state. Look how much Clinton was a friend, but he never said that.” Bush’s order to Sharon to pull out of the Occupied Territories also made a lasting impression on Khufash, for different reasons. “I learned this word from Bush: He said Pull out ‘without delay.’ I found out what means ‘without delay.’ It means right now.”