Still Searching

Jennifer Harbury Takes Her Ten-Year Odyssey for Justice to the Supreme Court

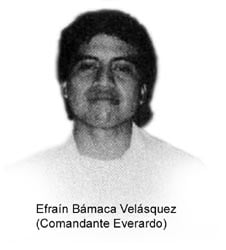

Every year on the twelfth of March, Jennifer Harbury sends a dozen roses to the Guatemalan Embassy. This year she was in Washington, preparing to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court, and delivered the bouquet on her way to the law library. It was exactly 10 years ago to the day that the Guatemalan army captured her husband, Efraín Bámaca Velásquez, after a minor skirmish in a war that had gone on forever and taken a dreadful toll: 200,000 people—most of them Mayan Indians—killed or disappeared; one million people displaced; 626 massacres; 440 villages wiped off the map in the worst episode of genocide in the Western Hemisphere in the twentieth century.

At the time he was captured, Bámaca, whose nom de guerre was Comandante Everardo, was not yet 35. He had spent 17 years as a guerrilla in the mountains and was one of the highest-ranking Mayan leaders of the rebel forces known as the URNG (Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca). He knew precisely the kind of things his captors would want to know—as well things in which they would probably have no interest at all. He spoke Mam and Quiché, as well as Spanish, and although he had had no formal schooling, was a voracious reader who sometimes wrote poetry. As Harbury stood on the sidewalk outside the Embassy, the Ambassador suddenly came running out the door. He asked about her case before the Supreme Court; she filled him in on the latest developments in Costa Rica, where she had won a major decision against the Guatemalan military at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. He said there was something he was curious about and had wanted to know: His staff told him that every year she sent a dozen roses—every single year. Why was that?

She explained that March 12 was the anniversary of Everardo’s capture; she still didn’t know the date of his death. The Ambassador asked about the colors. She sent different colors every year—was there a significance? No, she replied. They were just the colors that she liked. (This year they were peach.) And then he had one more question: “So why do you send them here?”

“You won’t give the body back, ” she replied. “I can’t take the flowers to a grave site, so as far as I’m concerned, this is the grave site until you give him back.”

And then he stood there staring at me for a while, and just wished me well,” Harbury recalled not long ago, when we met in the Rio Grande Valley town of Weslaco, not far from the Legal Aid office where she represents migrant farmworkers. “I expect nothing but more smoke.”

For the past 10 years, Jennifer Harbury has been slogging through lies, dodging the smoke and mirrors trying to find out what really happened to Everardo. She stood by as bodies of victims of the Guatemalan army were exhumed; lobbied endlessly for answers at the U.S. Embassy, the State Department, and in Congress; brought witnesses out of Guatemala to testify before the Human Rights Commission of the Organization of American States; and sat in the office of the Guatemalan Minister of Defense, attempting to negotiate Everardo’s release. She conducted one hunger strike in front of the Politécnica, Guatemala’s National Military headquarters, and then another for 32 days in front of the National Palace. It was not until November 1994, when the television show “60 Minutes” aired a broadcast revealing that the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala did, in fact, possess information indicating that Everardo had been captured alive, that the State Department acknowledged that it knew he had not been killed in combat or committed suicide—as the Guatemalan army had initially reported—but had been captured and held in a clandestine military prison. On the third anniversary of Everardo’s capture, she began a hunger strike in front of the White House. She was repeatedly told by the American Ambassador in Guatemala and other officials that they had no further information about what had happened to her husband. Then in March 1995—on the twelfth day of her third hunger strike—she was summoned to the office of then-Congressman Robert Torricelli. It was there that she was told the truth—or as much of the truth as Torricelli had pieced together—that Everardo was dead, his killing ordered by Julio Roberto Alpírez, a colonel in the Guatemalan Army, a graduate of the School of the Americas in Ft. Benning, Georgia, and a CIA asset who was also linked to the 1990 murder of American citizen Michael DeVine, an expatriate innkeeper.

Torricelli’s revelations caused an uproar. The Clinton Administration should “announce that America will no longer train and encourage Latin American thugs,” thundered The New York Times. “It can make an even stronger case for thorough, systemic reform of the CIA to make it lean, honest, less wasteful and more accountable for the millions of taxpayer dollars it spends.” The President ordered an investigation and in June 1996, the Intelligence Oversight Board released a 61-page document, which stated that the CIA had a relationship with Guatemalan military intelligence and criticized the CIA for failing to properly inform Congress about human rights violations. It concluded that Alpírez had taken part in a cover-up of DeVine’s murder and participated in Everardo’s interrogation. “We believe, but lack definitive proof,” the report continued, “that interrogation included torture.” As to Everardo’s fate, the Board concluded that he had been killed within a year of his capture and offered three possibilities: He had been flown in a helicopter and dumped at sea; he had been dismembered and his remains scattered so they would never be found; or he had been buried at a military base known as Las Cabañas. “Although the Board believes that assets or liaison contacts were likely involved or knowledgeable,” the report stated, “it found no indication that the CIA was aware of these links at the same time.”

Among the documents made public at the same time was a September 1993 Department of Defense intelligence report that noted that clandestine military prisons had always existed in Guatemala, and that guerrilla prisoners were commonly held incommunicado in isolated military zone locations, interrogated, and killed after the army had extracted all useful information from them.

Meanwhile, Harbury had begun piecing together documents released from her own Freedom of Information Act lawsuit against the CIA; from the National Security Archive, a non-profit research organization based in Washington, D.C.; and from information from witnesses inside and outside of Guatemala. Slowly she was cross-referencing the facts, working her way through the courts in the United States and in Central America. In addition to her FOIA suit, she filed a federal civil rights suit in Washington, D.C. against former Secretary of State Warren Christopher, former National Security Council chief Anthony Lake, former U.S. Ambassador to Guatemala Marilyn McAfee, several former directors of the CIA and other high-level Clinton Administration officials. The case has never gone to trial; in March 1999 a district court judge dismissed most of her claims. In December 2000, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia reversed the dismissal on one key claim, holding that Harbury’s right of access to the courts had been violated. “If her allegations are true,” wrote Judge David Tatel, “then the defendants’ reassurances and deceptive statements effectively prevented her from seeking emergency injunctive relief in time to save her husband’s life.”

Christopher and the other government officials petitioned the Supreme Court to review the case, and it was argued last March. Sometime this month the Court is expected to issue a decision in the case of Christopher v. Harbury, addressing a deceptively narrow question of constitutional law: Did Warren Christopher, Anthony Lake, and other high-level Clinton Administration officials deprive Jennifer Harbury of her right to access to the courts by repeatedly lying to her, withholding information about her husband’s secret detention, torture, and eventual murder?

About a year ago, I started following Harbury’s cases as they made their way through two very different court systems. I began wading through transcripts filled with characters like Asisclo Valladares, the middle-aged, heavy-set Attorney General with manicured nails and an expensive suit, who 10 years ago rushed off an army plane to stop an exhumation that would have proved that the Guatemalan army had committed a hoax and substituted the body of another man for that of Everardo. Or Simeón Cum Chuta, a military intelligence “specialist,” with a buzz cut, dark glasses, and barely audible monotone voice, who was one of Everardo’s torturers. Over and over again I read through the baroque prose of the Intelligence Oversight Board, along with the declassified memos made public by the National Security Archive’s Guatemala Project. From time to time I was reminded of a lawyer I know who likes to quote Leonardo Sciascia whenever the subject of “political crimes” is mentioned. Sciascia is a brilliant Italian writer who chronicles the murky world of politics and mafia in his native Sicily. Sciascia’s rule number one is that political murders are never solved; occasionally a name and a face are attached to the trigger man, the sicario, the low-life paid to do the dirty work, but never the asesino intellectual.

The larger truth in Guatemala is the one that scholars and independent journalists had been telling for years about the scope of the atrocities and the role of the United States. But it was not until a U.N.-sponsored truth commission issued its final report in 1999 that the full extent of the horror was known. The Guatemalan army and other state-sponsored forces were responsible for 93 percent of all the atrocities committed during the 36-year civil war. The Commission found that the military had committed genocide, and it found that the United States shared in the responsibility for what had happened in Guatemala. In 1954, a CIA-sponsored coup toppled the democratically elected government of Jacobo Arbenz and went so far as to provide the military government that followed with a list of assassination prospects. The United States subsequently funded, trained, and collaborated with the Guatemalan army and military intelligence.

“We have condoned counter-terror; we may even in effect have encouraged or blessed it,” a U.S. diplomat named Viron Vaky wrote in an uncharacteristically frank 1968 memo made public by the National Security Archive. “Is it conceivable that we are so obsessed with insurgency that we are prepared to rationalize murder as an acceptable counter-insurgency weapon?”

The worst of the atrocities took place in the late 1970s and early 1980s, under General Fernando Romeo Lucas García and later under General Efraín Rios Montt, the current president of the Guatemalan Congress. Most of the victims were Mayan civilians. Twenty years ago, Rios Montt defended his scorched earth policy with the phrase: “The guerrillas are the fish; the people are the sea. If you want to catch the fish, you have to drain the sea.” And so men like Julio Roberto Alpírez, “matured,” to borrow a term from CIA intelligence reports, in the killing fields of Guatemala, “where he participated in special intelligence operations which were tasked with eliminating insurgents and insurgent sympathizers.” And Ronald Reagan defended his good friend Efraín Rios Montt, saying that he had gotten a “bum rap” on human rights.

As a lawyer in Texas, Harbury began to come in contact with Guatemalan refugees in the early 1980s. No matter what had happened to them, no matter how awful their stories, there was little that a lawyer could do. Not only did INS routinely deny their applications for political asylum, INS translators in South Texas frequently had trouble with the phrase “escuadrón de muerte;” they were either unable or unwilling to call a death squad a death squad. Somewhat naively, as she would later write, she left Texas, where she had worked for Texas Rural Legal Aid and clerked for Judge William Wayne Justice, and in 1985 went to Guatemala. Intending to stay several weeks to document human rights abuses, she stayed two years. In 1990 she returned to Guatemala determined to write a book about the war and to interview guerrilla combatants in the mountains. It was then that she met Everardo, whose life she has described as “almost the mathematical inverse of my own, the other side of the looking glass.” She was a Harvard-educated lawyer, who had studied Chinese and traveled widely—Afghanistan, Africa, and Mongolia. Her father was a biochemistry professor who had come to the United States as a child from Holland, escaping the Nazis. The women in her family, she wrote in Searching for Everardo: A Story of Love, War, and the CIA in Guatemala, were “strong, bright, mulishly stubborn, and fiercely noncomformist.” Everardo was born on a coffee plantation, the eldest child of two Mayan peasants, and joined the guerrillas while he was still in his teens. He had been recruited by guerrilla leader Gaspar Ilom, who taught Everardo to read and regarded him as a son. Ilom, whose real name is Rodrigo Asturias, is the son of Guatemalan writer and Nobel laureate Miguel Asturias.

The couple fell in love, married in Texas, and in the fall of 1991 were living in Mexico City, where Everardo worked on the indigenous rights agenda to be presented during peace negotiations and Harbury worked on her first book, a collection of oral history.

But the negotiations had reached a stalemate, and in early 1992 he returned to Guatemala and soon after disappeared. At first the Army reported that he had fallen in combat and had committed suicide to avoid capture. A detailed description of a body that had been found in a river and buried by the army was sent to the URNG. In May 1992, Harbury traveled to Guatemala to exhume the body, only to be stopped at the last minute by Attorney General Valladares. In early 1993, a former guerrilla who had escaped from a clandestine military prison told her that he had seen Everardo being tortured in an effort to break him psychologically to collaborate with the army; he could identify about 30 other former guerrillas who had also been tortured and were being held clandestinely. Until that time, human rights organizations believed that Guatemala had no political prisoners—anyone captured by the army would be summarily executed. Armed with the names of both prisoners and military officials, Harbury approached the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala in March 1993. In August of that year, she was finally able to open the grave and discover what Valladares had tried to prevent her from learning—that there had been a hoax, that the body was not Everardo’s but that of a much younger, shorter man, who had been killed to provide a corpse. It was precisely the kind of scenario predicted in a CIA memo issued just six days after Everardo’s capture and distributed to the State Department, White House, and other government entities—the Guatemalan army would likely fake his death, the memo stated, “to maximize his intelligence value.”

“Señoras y Señores, La Corte.” The Court is the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, located in a pleasant hillside suburb of San Jose, Costa Rica. It has no street address and when I call for directions, I am told with typical tico, or Costa Rican informality—to look for a building 100 meters from a coffee shop called Pastelería Spoon. The building is one that would not be out of place in any wealthy suburb south of the Rio Grande; the courtroom itself looks more like a simple chapel with its wooden beams and whirling ceiling fans.

The Court, to which the United States has never belonged, is part of the Organization of American States. It is not a criminal court; its goal is to protect and promote human rights and it can only accept cases that cannot be prosecuted in domestic courts. In her search for Everardo, Harbury began with the Guatemalan courts, but was thwarted by judicial officials who spent most of their time trying to invalidate her marriage, or alternately trying to prevent her from leaving or entering the country. She was repeatedly threatened, as was an independent prosecutor who was finally forced to resign. His successor, whom the army had blocked from carrying out any further exhumations, was shot to death in May 1998. Like so many killings in Guatemala today, the prosecutor’s murder could easily be attributed to common crime and was never solved.

In November 2000 the Court issued an 80-page decision that found the Guatemalan military guilty of the secret detention, torture, and execution of Everardo, of the violation of the civil rights of Jennifer Harbury and Everardo’s father and sisters, and of obstruction of justice. Human rights activists in Latin America heralded the decision as a message to military officials throughout the region; the tactics of the “Dirty Wars,”—secret detention, torture, and extra-judicial execution—had been officially declared illegal by a panel of Latin American judges.

The decision was the culmination of an extraordinary war crimes trial that had taken place in June 1998. Among the witnesses was Helen Mack Chang, who had been trying for years to have her sister’s killers brought to justice. Myrna Mack, a leading Guatemalan anthropologist, was stabbed to death in 1990 because of her work with rural communities displaced by the violence. Testifying as an expert witness, Helen Mack described justice in Guatemala as inefficient, slow, and plagued by impunity. She pointed to the recent murder of Bishop Juan Gerardi, the founder and director of the Guatemalan Archdiocese’s Office of Human Rights. On April 24, 1998, Gerardi had presented Guatemala: Nunca Más (Never Again), a 1,400-page report of the atrocities committed during the war, which concluded that the army was responsible for the vast majority of them. Two days later he was bludgeoned to death. His murder sent a chilling message to human rights advocates and those seeking to use the judicial system to end impunity. Mack told the Court that despite the peace accord that went into effect in 1996, a “parallel” power structure continued to operate; until that parallel structure was dismantled, nothing would change.

The Court also heard from two former guerrillas who had been taken prisoner, tortured, and forced to collaborate with the army as they were moved from one clandestine location to another, a practice that had been pioneered in Argentina during the Dirty Wars of the 1970s. Former guerrilla Santiago Cabrera López testified that he had last seen Everardo in July 1992; Everardo was half-naked, tied to a bed, his body swollen, his arms and legs bandaged, a cylinder of some unknown gas next to his bedside.

Although Harbury had written two books on Guatemala and told her own story countless times, she had never told it in a court of law until the trial in San Jose; it was the only time she had ever broken down in public. “You try 20,000 things, but it’s never enough,” she told the Court. “You feel, ‘Why aren’t I more intelligent or why aren’t I more creative, why aren’t I stronger, why am I failing this person, my husband?’ And learning that’s he’s dead, I’ve failed him again. I can’t even give him a decent burial… So, I’ve failed him twice.”

Former Attorney General Valladares, Colonel Alpírez, and other Guatemalan government and military officials had been subpoenaed, but did not show up. Instead, five months later another hearing was held and several of them—but not Colonel Alpírez—came to Costa Rica. (Some first called the court to ask whether they would be arrested and jailed when they stepped off the plane. That October, General Augusto Pinochet had been arrested on human rights charges while visiting England; the Guatemalan military officers feared meeting a similar fate in San Jose.)

One by one they told the same story: They worked in military intelligence, but knew nothing about Everardo except what they read in the news. There had been no clandestine prisons in Guatemala. There were former guerrillas (guerrillas were sometimes described as delincuentes terroristas) who gave themselves up voluntarily and worked on the military base. There had been some sort of military trial in Guatemala, but they knew nothing about it and there were no charges against them. (A military court had indeed found them not guilty; neither Harbury nor her witnesses were ever questioned.)

By the time the Court issued its decision, the findings of both Bishop Gerardi and the U.N. Truth Commission (in which the case of Efraín Ciriaco Bámaca Velásquez is discussed at length) had been released and were later introduced into the record. The Court did not have to make individual findings of guilt—the pattern and practice of forced disappearance committed by the army had already been well established. Harbury and her witnesses were deemed to be credible and the Court issued its landmark decision.

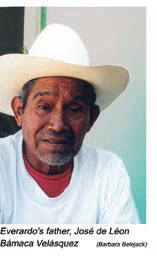

In November 2001, she was back in Costa Rica for a hearing on reparations, along with Everardo’s father, sisters, and baby nephew—also named Everardo. Harbury had told me that she thought the proceedings were likely to be dry and technical, but they were not. Despite the grim subject matter, the hearing seemed to restore the judicial process to its most basic ritual function—telling a story, bearing witness, and educating us about the past. One of the justices acknowledged that the Court was grappling with complex philosophical questions present in any case of wrongful death—How do you value a human life? What might Everardo’s life have been like in post-war Guatemala? They were uncomfortable questions, as the Court itself recognized. (One of the judges was so taken with the moral and cultural issues that he wrote a separate opinion with a side discussion of Sophocles’ Antigone.)

Harbury had long ago signed away her own right to any monetary damages, which would all go to Everardo’s family in Guatemala. She went through her story one more time, and the attorneys for the government of Guatemala expressed little interest. In fact, in two days of testimony, with expert witnesses on conditions in Guatemala, Mayan culture and the significance of burial rites, and the effects of post-traumatic stress, the only time the attorneys for the Guatemalan government seemed to come alive was during the testimony of Manuela Alvarado, who had served as a deputy in the Guatemalan Congress.

Just a decade ago it would have been unthinkable to imagine a Quiché woman dressed in her traditional huipil, or blouse, and skirt, elected to serve in the Guatemalan Congress. That had changed with the signing of the peace accords, which went into effect in December 1996. But overall the accords had failed to live up to the expectations they had generated. “They disarmed us, but they never inserted us into society,” Alvarado said, a capsule description of the first five years of the peace accords, as well as the current state of indigenous rights.

During the trial, in the presence of Everardo’s father, the attorneys for the Guatemalan government suggested that Everardo’s hypothetical life earnings would have been minimal, since he had been a campesino with no formal schooling who joined the guerrillas. Now they were trying to distinguish his hypothetical post-war career possibilities from those of Alvarado, a nurse and teacher, who had never joined the rebel forces. They were not quite ready to see Everardo as she did—a natural leader.It was still another variation on a theme played often by the Guatemalan military, which had urged that a different standard be applied to rebel combatants. But the Court hadn’t bought the argument during the trial, and ruled that it didn’t matter whether someone was “metido en algo”—mixed up with something, a catch-all phrase the military had used for so long to justify its conduct.There were minimal human rights standards that applied to everyone.

The strategy didn’t work in the reparations hearing, either. In February the Court issued a decision requiring the government of Guatemala to pay approximately $500,000 in damages and legal fees to the family of Everardo. Compared to U.S. damages awards, it was a modest amount. (And somewhat less than the $540,000 the Guatemalan Defense Ministry had paid to a Washington, D.C. public relations firm in 1995, in a futile effort to boost its image.) But the award was consistent with what the Court had ordered in other cases and in keeping with its mission. It also ordered the government to publish its original decision in a major daily newspaper, and gave the military six months to produce Everardo’s remains—the first time the Court had ever made such a demand in a case of forced disappearance. Finally, it ordered the government to hold judicial proceedings to investigate his murder and punish those responsible. The decision all but guaranteed that Harbury would return to Costa Rica for endless enforcement hearings. But first there would be a trip to Washington, D.C.

On the morning of March 18, the visitors’ line at the U.S. Supreme Court was unusually long. Only a handful of those who had been waiting for hours in the cool, gray drizzle of late winter would make it up the stairs, into the building, through the multiple security checks, and into the crowded courtroom. The Court would hear two cases that morning. The first involved securities law and fiduciary duties and inspired a lively round of questioning. The petitioner’s attorney had barely finished his first sentence when Justice Scalia interrupted. Scalia seemed to take great interest in the case, as did the other justices, with the exception of Justice Thomas, who characteristically said nothing the entire morning.

At 11 a.m. sharp, Richard Cordray, an Ohio attorney who specializes in government immunity cases, stepped up to the podium to argue that Warren Christopher and other former government officials had not violated Jennifer Harbury’s rights. Or if they had, they were protected by qualified immunity. Cordray had filed his petition for Supreme Court review in early September, just days before the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. In the aftermath of September 11, the case had taken on a different dimension. In the best of times, federal courts are wary of encroaching upon foreign policy and national security arenas. These were not the best of times. Moreover this was a Court that had not hesitated to designate a president after the 2000 election; it was unlikely to do anything that might remotely infringe on his conduct of foreign policy. Cordray’s job had unexpectedly become much easier.

Because of the way the case had moved procedurally, Cordray had not yet raised a “foreign affairs” or “national security” defense. But the Pentagon had been attacked, the nation was at war, the Solicitor General—who had argued the President’s election case before the Supreme Court and would be joining Cordray as a friend of the Court in oral argument—was a recent widower. Ted Olson’s wife, Barbara, had perished on the plane that crashed into the Pentagon. Two former CIA directors—former President George Bush and James Woolsey—had been quick to blame the 1995 human rights reporting regulations imposed on the CIA following revelations about Guatemala for the intelligence failure that led to 9/11.

“What’s at stake is covert operations,” Cordray argued in his brief to the Supreme Court, “and that has direct ramifications for Afghanistan,” an argument he hammered home before the Court. “We’re in the sensitive context of foreign policy and the oversight of covert operations in a foreign country.” He described Harbury’s claim as a “long skein of hypotheticals,” at the end of which was “a notion that an American court order would somehow have prevented the Guatemalan military from executing her husband.”

First Cordray and later Olson argued that a ruling in favor of Harbury would stifle communication between government officials and ordinary citizens, thousands of communications that take place every day. One of the most common forms of communication, as Olson described it, was the “equivocal and innocuous ‘I will get back to you.'” That, he insisted, was the essence of Harbury’s case—a half-hearted promise on the part of Marilyn McAfee, the U.S. Ambassador to Guatemala and other State Department officials, to look into things; an innocuous, “I’ll get back to you,” should not result in a lawsuit. Furthermore, Olson maintained that the government had an inherent right to lie: “There are lots of different situations where the government quite legitimately may have reasons to give false information out.”

And then it was time for Harbury. Until recently she had been represented by a team of pro bono lawyers, but when the Court agreed to review the case, she decided to argue it herself. Her decision sparked the interest of the press, which over the years seemed to have trouble grappling with the fact that it was possible to be a Harvard-trained lawyer, political activist, and the widow of a Guatemalan guerrilla leader at the same time. Perhaps the justices—who were not used to hearing directly from the parties before them—would be equally perplexed.

She began by telling the Court that the case turned on “a very narrow question of law,” a long opening statement that ended with the words “secret cell,” “severely tortured,” and “imminent danger of imminent execution.”

“Ironically I note that today this case is in the highest Court of the land,” she told the Court, “but it is exactly 10 years and six days too late,” a reference to the first CIA memo about Everardo’s capture. Denial of access had proven fatal.

“Access to court to do what?” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asked in a hesitant voice. “What claim could you state?” Harbury took that as her cue to argue her case within a case, to outline the kind of relief she would have asked for years ago if she had had the information she needed. She would have asked for an order prohibiting the CIA from requesting and paying for information obtained through torture, an order prohibiting the agency from failing to supervise its Guatemalan employees, prohibiting CIA officials from failing to disclose what they were required to disclose to Congress. “Any court faced with torture and the possibility that someone tomorrow may be literally thrown from a helicopter,” she told the Justices. “I do not believe that any court in this country could not have acted swiftly to redress that situation.”

She fielded questions on a wide range of case law and procedure, but in contrast to the previous case, the response from the bench had slowed considerably. Scalia limited himself to a paltry few questions, as did Chief Justice Rehnquist. Justice Breyer asked a long and winding question that began with “obviously reading your story, one is immediately sympathetic,” and ended with a variation on the issue of executive branch responsibility for foreign affairs. “When there’s egregious behavior throughout the world,” he asked Harbury, “How can we distinguish this case from the general problem of foreign relations, from the general problem of the CIA, from things that courts by and large don’t get into?”

This was not a case about sensitive, national security information, she told the Court. (Indeed officials later indicated that much of the information that it took so long for Harbury to receive was not “sensitive” and could have been provided much sooner.) Nor was this a case that asked the Court to interpret the U.S. government relationship with the Guatemalan military. (But even if it wasn’t, she made sure that the Justices knew that the United Nations had later determined that the Guatemalan military had engaged in genocide against Mayan peasants during the war.)

Finally, she insisted that the facts in her case would not result in a flood of litigation; this was not about an innocuous promise to get back to her.This was a case about government officials who had repeatedly lied to her. Had they not lied to her and assured her there was no further information, she would have gone to court years ago and made the same argument she was making now: “When you have an extremely close and supervisory relationship with a given informant for years, you know that they are notorious as a torturer and that, in fact, they were engaged in a liquidation campaign against civilians, and you say, ‘We want more information from the living prisoner in that room. You have the cattle prod and the pliers, here’s a check for several times–maybe ten or 20 times your annual income–would you please get that information for us?’ That is crossing the line. That’s crossing a very bright line that our government has never permitted. Our government has allowed under certain circumstances to take life, never to torture.”

It was an image that provoked a long and awkward silence from the Court; it was a different perspective from the one that the Justices were accustomed to hearing.

A month later I met with Harbury in Weslaco. and asked her about the awkward pause that silenced the Court at the end of her oral argument. It was a good pause, she told me, an intelligent pause: “They should think about taking out a checkbook for a cattle prod. It’s all too easy to sanitize documents and language so that you can come up with a quick and easy decision without having to worry too much about it. It’s like calling Auschwitz ‘the final solution’ instead of ‘the death camp’… If there’s going to be a ruling from the Court making conduct like that legal, I want it to be very clear what that conduct really is.”

She had no illusions about which way the Court would rule–they would throw out her case, saying the facts weren’t pleaded sufficiently, or that questions of foreign affairs are outside the purview of the Court. Rehnquist, she suspected, would just as soon get rid of the whole body of law on access to the courts. The consequences to her pending claims (only the Constitutional claims have been decided so far; there are still pending tort claims in the district court) would depend on the way the Court writes its decision. But Harbury was also thinking in Mayan time; she had her eye on the long run. “It matters to me what goes on the record 100 years from now. Someone can read that transcript and it’s clear as a bell–that people working for the CIA and other branches of our military overseas are out of control. They have their own political agenda. They consider themselves above the law and they do carry out de facto terrorist-like actions on many occasions.”

Meanwhile, there were still wage and hour cases to do for migrant farmworkers in Weslaco. And there was also a box of de-classified intelligence documents that had appeared out of nowhere just before she went to Washington. There was no time to review them while she was preparing for oral argument, but now she was slowly working her way through heavily redacted reports, most of which held nothing of interest. Two documents, however, referred to Colonel Alpírez and drug-trafficking. The allegations themselves were nothing new, but these documents also linked Alpírez to a Guatemalan military officer and drug trafficker named Carlos René Ochoa Ruiz. Ochoa Ruiz had been indicted by a grand jury in Florida in 1990 in what was supposed to be a major DEA test case, and was also linked to the murder of a Guatemalan judge who had tried to extradite him. It was all part of an endless chain that very likely had begun with the death of expatriate innkeeper Michael DeVine in 1990 and led to a very deep black hole.

I once asked Harbury if she thought she was ever going to run out of options. She didn’t think so.

“Someone got real creative with Pinochet and started new ways of dealing with human rights problems,” she noted. “We’ve slid backwards awfully far since September 11. We need to pick up the pieces and rebuild. All of us–people in the Chilean movement, and the Argentine and the Salvadoran movement–we need to figure out a forum where the U.S. will not be above the law. If the Supreme Court comes out and says this case can’t go to trial, then they’ve said that U.S. officials in this kind of case are above the law,” she said. “The U.S. has always been very careful not to subject itself to jurisdiction in any court. They’re not subject to jurisdiction in the Inter-American court, but people have to be responsible for what they do. It may take me a few years.” But she had lots of company–Helen Mack and so many others in Guatemala, the mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina, the people who had “gotten creative with Pinochet” in Chile.

She is 50 now, a milestone she cursorily marked with a birthday cake after speaking at an anti-war rally. (The best birthday, she wrote in Searching for Everardo, was the one she spent camped outside the National Palace in Guatemala during her 32-day hunger strike.) When I suggested that she would be working on these cases forever, she looked at me as if I had just announced that the world was round.

“Of course,” she said. “I’m a lawyer. What else would I do?”