Review

Welcome to Lonelyville

A book of short stories is a curious thing. Each component story could be anything. In one, the protagonist may be a meth-addled architect who imagines he’s Nebuchadnezzar. In another, it may be a 10-year-old girl waiting for the mail. As I understand it, the only requirement of a short story is that it suspend moments in time so that those moments can be fully experienced. Most authors treat short story collections like mix tapes: a little high, a little low, an overarching theme and a satisfying resolution, like the feeling of arriving in your own driveway after a long trip.

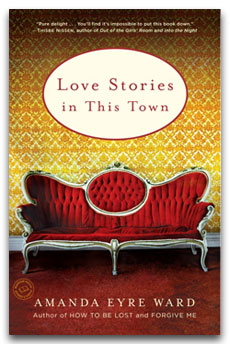

Not Amanda Eyre Ward. The 37-year-old Austin-based author of three novels (Forgive Me, How to Be Lost, and Sleep Toward Heaven) has just published Love Stories in This Town, a collection of 12 stories that seem like minor variations on a theme, or multiple alternate universes inhabited by a single character. Moreover, while the book’s theme is purportedly the importance of place, Love Stories in This Town seems much more convincingly a study of loneliness.

Part One comprises six stories in six locations with what one assumes was meant to be six discrete protagonists. Part Two is called “Lola Stories,” and its six tales dip in and out of the life of the title character and her relations. Read back to back, the female protagonists blur and smudge into a single character: American, white, and middle-class. She has a liberal education and doesn’t make much money. In “Should I Be Scared?” she has a B.A. in anthropology and works at a ceramics-painting studio. In “Butte as in Beautiful,” she’s a librarian. In “Shakespeare.com,” she’s a “content editor” at a flailing startup. Her husband is usually a scientist (“The Stars Are Bright in Texas”), specifically a geologist (“Should I Be Scared?”), and always a supportive and tender partner.

Whose wife wants a baby. My God, how she wants a baby. Two of the first six stories center on the early end of a pregnancy; in another the protagonist is pregnant; in still another, the protagonist’s sister is enviably pregnant. The Lola stories alone feature three pregnancies. It eventually becomes clear that Ward’s baby-crazy protagonist is looking to motherhood to provide her with purpose and cure her implacable loneliness.

Loneliness sounds like a terrible theme for a book of short stories. Who wants to tongue the grooves of modern isolation? But Ward makes a subtle pleasure of the experience, like the resolution of a minor chord or a gently pressed bruise. Her language is simple-colors are blue and yellow, never cerulean or mustard-and careful. Her protagonist is a woman a little apart from the world, observant and sensitive. She needs her space; she’s always slipping away to the bathroom, or to the kitchen for another drink. And she’s alone. Ward describes not a single strong female friendship or support system or companionship for her character other than a kind, patient husband and a trying family.

Ward’s three strongest stories are the ones that deviate from her married-with-baby-issues character, and all three center on the strange bonds forged by terrible need. The young librarian of the book’s second story, “Butte as in Beautiful,” is a valedictorian whose dreams of going to college on a basketball scholarship deteriorate with her wounded knee. It begins with the memorable line, “It’s a crappy coincidence that on the day James asks for my hand in marriage, there is a masturbator loose in the library.” (Ward has a thing for these hand-flashing openers; the next story starts, I think regrettably, “They told us the baby was dead, and two days later we were on a plane to Texas.”) What’s so beautiful about the Butte story is that the librarian’s feelings are veiled even to herself right until the last sentence, when a moment of truth with a lonely stranger blossoms into an insight as authentic as it is unexpected.

“Nan and Claude,” the second Lola story, explores Lola’s mother’s relationship with her hairdresser, Claude. When Nan is first married and feeling out of place in her new community, she splurges on Claude’s services, and he gives her the cut, the color, and the confidence she needs to integrate. He treats her like the country club natural she wants to be, and she regales him with stories of parties and business successes. When her husband abandons the family and Nan goes from taking tennis lessons to giving them to her contemporaries at the club, she doesn’t have the heart to tell Claude. Instead, she maintains a shining mirage of marriage and familial joy. In turn, Nan never mentions the lesions that erupt on Claude’s arms, and when loose talk forces him to close his salon and start doing hair out of his home, she follows him there. Ward’s light touch is perfect here. The story is sad, of course, but it’s not maudlin, and the respect that Claude and Nan show for one another’s fig-leaf lies is a tender, true kind of love.

Ward’s deft, almost aloof treatment is also integral to the success of a sister story, “The Way the Sky Changed,” wherein a man and woman who lost their spouses in the 9-11 attacks begin to date. Like Claude and Nan, their relationship is built on a wordless lie. The two are set up by concerned loved ones, and after a dismal first date decide to visit a hamburger place the protagonist once frequented with her husband.

When Jan came to take our order, she looked surprised to see me with a date, then angry, then sad.”What do you recommend?” Kent asked Jan.”Oh, get a cheeseburger,” I said. Paul and I always ordered cheeseburgers.”The tuna steak sandwich is good,” said Jan. She looked Kent up and down … “The cheeseburgers are really the best,” I insisted. “I think I’ll try the tuna steak sandwich,” said Kent. He looked at me with a smile, but he must have seen something in my face. He blinked, and I looked down at my menu. “Wait,” said Kent, reaching out and touching his fingers to Jan’s arm. “I’ve changed my mind.”She wheeled around and raised an eyebrow.”I’ll have the cheeseburger after all,” said Kent.”You might even want to try fried onions on top,” I said. “Oh,” said Kent, “okay.”

Ward lets the truth behind their dating dawn on the reader the way it dawns on Kent at that moment, without ever spelling it out. If readers don’t catch it then, they’ll be awfully confused a few pages later when the protagonist “jazzes up” her outfits with Kent’s dead wife’s high heels. Their time together is brief, but to anyone who’s ever found companionship through mutual despair, it’s familiar.

Ward is at her best when rendering ambiguous, complex relationships like these. If she has a weakness, it’s evoking a sense of place. Rather than transport the reader to various semi-exotic locales through the senses-the smells, the weight of the air, the slant of light particular to a place-Ward relies on local restaurants, street names and landmarks to sketch in her settings. Stories transpiring in Austin, Houston and San Francisco are interchangeable but for the proper names of streets and restaurants. In an interview included with the book, Ward confides that her experience with a dot-com startup took place in Austin and that she transposed it to San Francisco for “Shakespeare.com.” Despite a fleeting mention of Birkenstocks and guacamole, “Should I Be Scared?” would be unplaceable if not for its shout-out to the Austin Chronicle. In “The Stars Are Bright in Texas,” the protagonist and her scientist husband search for a home in The Woodlands, a master-planned community north of Houston, and Ward’s brief description misses an opportunity to evoke the soul-sucking homogeneity of that socially engineered sprawl.

The one story in which the reader gets to linger on sensory details of place is “Butte as in Beautiful.” Our Lady of the Rockies, a hundred-foot statue of the Virgin Mary overlooking the historic mining town, is bleached “white as snow” by the arsenic in the air. “Butte bought her and helicoptered her up to the Continental Divide to give the town something to be proud of, when all the copper was gone.” In the smokestack of the old smelter and the old cars in the sun, the reader feels the thin, bright air and pawnshop sadness of Butte. Of course the statue was installed in 1985, four years after the arsenic-spewing smelter closed-but then again, this is fiction.

What Ward’s stories lack in diversity they make up in depth, which she achieves with seemingly effortless prose. Her thoughtful storytelling delivers insightful moments of uncommon tenderness. They linger, unattached to either time or place, less read than experienced-and isn’t that what short stories are for?

Contributing writer Emily DePrang lives in Pearland.