Hell No, They Won’t Go

One of the more disconcerting (if poorly publicized) effects of the last eight years of American foreign policy is that I’m now forced to admit there are things Pat Buchanan and I agree on.

It was so much easier during the reign of the first President Bush, when Buchanan was the happy culture warrior, fire-breathing his way across the country attacking gays, feminists, liberals and other degenerate life forms as he went, and I could hate the man and sleep comfortably. Now it seems like every time I turn on MSNBC, there’s Buchanan, condemning the second President Bush’s Iraq War, railing against his blundering efforts in Afghanistan, bemoaning his cowboy posturing toward Iran and Russia. And before I know what’s happening, I’m nodding my head and thinking, “Maybe Pat Buchanan isn’t such a bad guy after all.” Inevitably I end up turning the TV off in self-disgust, imagining my father turning somersaults in his grave.

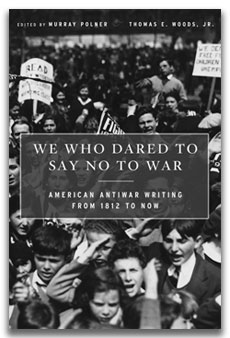

Turns out strange bedfellows are common in the history of American anti-war sentiment, as evidenced in the new anthology We Who Dared to Say No to War. Start with the book’s editors: Murray Polner is a staunch leftist whose writing has appeared in The New York Times and The Nation, while Thomas E. Woods Jr. writes for considerably more conservative publications like Investor’s Business Daily. Together they’ve assembled almost two centuries’ worth of writing condemning American military actions from the War of 1812 to more recent misadventures in the Middle East, while celebrating the fact that the noble cause of peace in this country has often attracted wildly opposing un-likes. Take, for example, the unionists and industrialists who joined forces in the American Anti-Imperialist League to oppose the Philippine-American War of the late 1890s. Surely labor leader Samuel Gompers and aristocrat Andrew Carnegie shared just about nothing in this world but the belief that by occupying the Philippines after the Spanish-American War, and by brutally putting down the resulting independence movement, the United States had betrayed its birthright as a freedom-loving country sprung from the shackles of colonial rule. With that one act, America sacrificed its reputation for the sake of an imperialist land-grab, “puk[ing] up its ancient soul,” psychologist William James would later write, “in five minutes.”

In a speech delivered at the 1900 Democratic National Convention deriding the American occupation of the Philippines, anti-Darwin populist William Jennings Bryan laid out the stakes for America. He articulated in biting prose what many writers in this collection believe: that the country’s colonial tendencies-first sensed as early as the War of 1812 (during which many supporters argued for the annexation of Canada), given greater definition by wars in Spain and the Philippines (after which we would claim Guam and Puerto Rico as our own, and a foothold in Cuba), brought to maturity during the run-up to the first World War, and eventually finding its full fruition in the jungles of El Salvador and the deserts of Iraq-run contrary to the spirit of American democracy, that they debase everything we claim to stand for and call into question every action we take beyond our own shores. “We cannot repudiate the principle of self-government in the Philippines,” Bryan writes, “without weakening that principle here. … Better a thousand times that our flag in the Orient give way to a flag representing the idea of self-government than that the flag of this republic should become the flag of empire.”

What good is it, in other words, being a beacon of liberty to the world when we’re so quick to make a mockery of liberty everywhere but at home?

It’s a question asked time and time again by America’s great conscientious objectors, but anti-imperialism is only one of the engines behind the anti-war polemics in We Who Dared. Throughout the course of American history, an enormous range of philosophical motivations-from the political to the economic, from the religious to the legalistic, from the ideological to the personal-has fueled the writings and speeches of anti-war members of Congress, intellectuals, journalists, unionists, clergymen and everyday citizens. During the Civil War-which has been so thoroughly romanticized that we forget there was a strong movement, even in the North, against its execution-radical abolitionists railed against the slaughter on religious grounds, claiming that attacking the sin of slavery with warfare was a tainted path to salvation. “I would not do evil that good may come,” writes slavery opponent Ezra Heywood. Civil libertarians pulled their hair out over Abraham Lincoln’s countless assaults on the Constitution, including the suspension of habeas corpus, the illegal arrests of thousands, and the censoring of hundreds of newspapers.

War, the argument goes, turns even great men bad. Watch us stoop to murder in our fight against murderers in Vietnam; marvel as we engage in torture in hopes of ridding the world of the torturer Saddam Hussein. Even wars in which we set out to do good end up corrupting because war is, by definition, a corrupting agent.

Which is why, for my money, journalist Milton S. Mayer’s 1939 article opposing American involvement in World War II, “I Think I’ll Sit This One Out,” is the most illuminating piece in the book. There is no war in American history, perhaps in human history, more lauded for the good it did, no war considered more necessary, no war where the lines between good and evil were so clearly defined. Where does one get the temerity to advocate against such a “good war”? How does one claim conscientious objection to a war against an enemy-Hitler-who was himself beyond conscience? How does one argue for the light of liberty in America while allowing the rest of the world to plunge into darkness? By claiming that in fighting Hitler, we risked becoming Hitler.

“If I want to beat Fascism,” Mayer writes, “I cannot beat it at its own game. War is at once the essence and the apotheosis, the beginning and the triumph, of Fascism, and when I go to war I join Hitler’s popular front against the man in men.”

Just as the anti-imperialists railed against wars in Cuba and the Philippines by arguing that America, in crushing insurrection, would become the very thing it abhorred, just as citizens worried about the rise of a militaristic American totalitarianism during the country’s “cold” war against the Soviets, so Mayer believed that America’s struggle against the forces of fascism would turn us into fascists. It would have to, he argued, because war is fascism. “Democracy,” he writes, “is an order in which the state exists for men, so Fascism is an order in which men exist for the state. And in no condition to which men submit do they exist for the state so completely as in war.” Mayer believed that any war conducted by a democratic country is a stab in the heart of that country’s identity and a compromising of its ideals.

Maybe that’s why war is so terrifying to so many of us, and so contrary to what we feel is the spirit of America. Liberty is the triumph of free thought and individuality over the violence and coercion of the state. And war requires no less than complete complicity from a country’s citizens in order to thrive. War isn’t horrible just for the bloodshed and malice it thrusts upon us, but for the inhuman mindlessness we inflict upon ourselves in supporting it.

“We have been taught to ring our bells, and illuminate our windows and let off fireworks as manifestations of our joy, when we have heard of great ruin and devastation, and misery, and death, inflicted by our troops upon a people who never injured us, who never fired a shot on our soil, and who were utterly incapable of acting on the offensive against us.”

That will sound familiar to anyone who remembers the early days of the Iraq War in 2003. What may be surprising is that it was written in 1849, by Congregational minister William Jay, assessing the Mexican-American War. War’s consequences, it turns out, are the same now as they were then: a debasing of the country’s reputation, a corruption of its ideals, a stain on its soul.

Democracy and war, these pieces collectively suggest, may be the strangest, and worst, bedfellows of all.

Josh Rosenblatt is a freelance writer in Austin.